Vaccines Could Prevent New Chronic Diseases After Covid-19

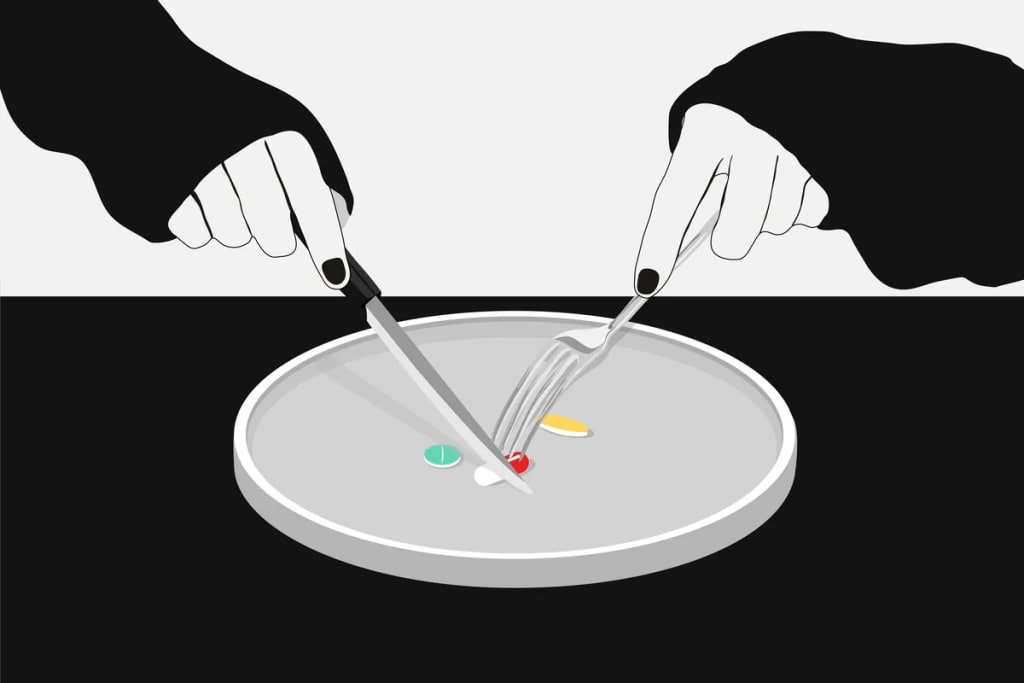

Post-Covid medical sequela includes hypertension, diabetes, heart diseases, thrombosis, mental disorders, etc.

Most of us are familiar with long-Covid, where Covid survivors may suffer persistent symptoms — usually fatigue, breathlessness, and brain fog — for months and, sometimes, years.

But not many know that long-Covid encompasses other subtypes too. One subtype is the medical or clinical sequela (MCS), where Covid-19 survivors face higher risks of new-onset chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular and neurological diseases, which is a major public health concern given the sheer number of people who have Covid-19.

The MCS subtype of long-Covid

In my research review published in Reviews in Medical Virology, I examined the entire long-Covid literature to parse this highly heterogeneous and multifaceted condition into six subtypes:

- Non‐severe COVID‐19 multi‐organ sequelae (NSC‐MOS)

- Pulmonary fibrosis sequelae (PFS)

- Myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)

- Post‐intensive care syndrome (PICS)

- Medical or clinical sequelae (MCS)

About the MCS subtype, large cohort studies have reported that Covid-19 survivors face higher risks of new-onset medical diseases than non-Covid controls. The reasons are that Covid-19 could damage organ systems and aggravate the health of those at risk of chronic diseases. Some researchers have called MCS the “unmasking of underlying comorbidities.”

For example, in an England study of 47,480 previously hospitalized Covid-19 survivors and 47,780 matched controls, the risks of new-onset respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes were 27-times, 5.4-times, 4.4-times, 2-times, and 1.5-times greater in the Covid-19 group at 140‐day of follow-up.

Moreover, within the 140-day period, 29.4% got re-hospitalized, and 12.3% died in the Covid-19 group — equating to the respective risks of 3.5-times and 7.7-times greater than the control group. (Only 9.2% and 1.7% in the control group got re-hospitalized and died, respectively.)

Similar results have been replicated in other large cohort studies, which I have previously detailed in my published research review. So, I’ll not go into the details here, but the overall picture is that Covid-19 survivors have been found to have higher risks of the following diseases:

- Cardiovascular diseases: e.g., heart attack, myocarditis, deep vein thrombosis, and stroke.

- Respiratory diseases: e.g., acute/chronic respiratory failure, interstitial lung diseases, and pulmonary thrombosis.

- Neurological disorder: e.g., peripheral neuropathy and dementia.

- Mental health disorders: e.g., depressive and anxiety disorders.

- Others: e.g. chronic liver and kidney diseases, diabetes, and obesity.

As a result, the MCS subtype of long-Covid is often accompanied by increased risks of new medication prescriptions, such as anticoagulants, antiarrhythmics, bronchodilators, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, anti-inflammatories, hypoglycemic agents, anti-asthmatics, anti-lipidemic agents, and antidepressants.

Vaccines could prevent MCS of long-Covid

In a recently published, titled “The Protective Effect of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccination on Postacute Sequelae of COVID-19: A Multicenter Study From a Large National Health Research Network,” Zisis et al. from Case Western Reserve University, Ohio, capitalized on the TriNetX database that stores data on adults (aged ≥18 years with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection) who sought medical care in the U.S.

Zisis et al. then matched 25,225 vaccinated + infected adults (breakthrough infection) to 25,225 unvaccinated + infected adults in terms of age, sex, race, BMI, and comorbidities (e.g., heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, etc.) from 21 September 2020 to 14 December 2021. And they computed the risk of several chronic medical diseases between the two groups.

At 90-day follow-up, vaccinated + infected adults had 19.1%, 13.2%, 13.1%, 9.2%, 7.8%, 7%, 6.9%, 5.4%, and 0.6% absolute risk reduction in new-onset mental disorders, hypertension, heart diseases, thrombosis, death, diabetes mellitus, cancer, thyroid disease, and rheumatoid arthritis, as well as 43%, 26%, 24%, 15%, and 9% absolute risk reduction in new-onset respiratory symptoms, fatigue, diarrhea or constipation, headache, and body ache compared to unvaccinated + infected adults.

“In our study, vaccination against COVID-19 is associated with a lower risk of outcomes that have not been assessed in previous studies — namely, new-onset diseases [and] new-onset symptoms known to be part of long COVID syndrome,” Zisis et al. stated. “As such, our work [shows] that vaccination is associated with faster and better COVID-19 recovery.

Similar risk reductions were also observed at 28-day follow-up, suggesting that “there was enough evidence to suggest that these differences were attributed to the vaccine,” the study authors wrote.

But like any other study, the study of Zisis et al. also has limitations. First, only breakthrough infections were analyzed, so the study can’t tell if the risk reductions apply to those vaccinated after infection. Second, it’s an observational study, which, by default, can’t prove causation. Third, the vaccination rate was low, so certain vaccinations may have been missed. Fourth, some underlying behavioral or socioeconomic differences might be present between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, which may have possibly skewed the results. Fifth, vaccine type was not assessed, so the study can’t tell if any vaccine-specific effects are present.

Notwithstanding these caveats, the study of Zisis et al. still offers great value. The risk reductions were quantified in absolute terms, not relative terms, which is more meaningful*. And most of the effect sizes were high (>10% absolute risk reduction), indicating that the effects seen are likely real rather than a result of other confounding variables.

*Absolute risk: 20%–10% = 10% reduction. Relative risk: 20%/10% = 50% reduction.

Moving on, a meta-analysis of 18 studies calculated that vaccinated people (mainly with mRNA vaccines) have a 29% lower relative risk of developing long-Covid symptoms than unvaccinated people.

Subgroup analyses then revealed that vaccination showed this effect after two doses, not one. Interestingly, the subgroup analysis also showed that vaccination was effective in preventing long-Covid in either case of vaccination before or after Covid-19, suggesting that Covid-19 vaccines are effective at attenuating long-Covid arising during or after Covid-19.

During Covid-19, the vaccine may prevent the huge health toll that severe Covid-19 puts on the body, thus reducing the risk of long-Covid afterwards, for we know that severe Covid-19 is associated with long-Covid. After Covid-19, the vaccine may eliminate reservoirs of SARS-CoV-2 persistence in the body, thus alleviating long-Covid symptoms.

But this meta-analysis mainly examined long-Covid symptoms. So, the study of Zisis et al. is valuable as it discovers another benefit of the Covid-19 vaccine — i.e., lowering the risks of new-onset long-Covid symptoms and chronic medical diseases — which must be considered when assessing the risk-benefit ratio of Covid-19 vaccines.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This article was initally published at Microbial Instincts.

About the Creator

Shin jie Yong

MSc (Research) | 13x (10x first-author) academic papers | Independent researcher and science writer | Named Standford's world's top 2% of most-cited scientists | A powerlifter with national records

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.