Fixing it in Post

How the United States Government Has Reshaped its Role in the Overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz

In 1954, Jacobo Arbenz had been the President of Guatemala for three years. When Arbenz took power in 1951, he had no idea that continuing his predecessor’s crusade for Guatemala’s peasantry would draw him into the crosshairs of the United States government.(1) His predecessors had ruled Guatemala in the American business-friendly fashion expected by the United States government. Arbenz’s mild attempts to transform the Guatemalan economy from a feudalistic state into a capitalist one drew the ire of the United States government via the interests of U.S. businesses operating in the country.(2) For most Americans, greater threats to "national security" have overshadowed knowledge of Operation PBSUCCESS and the events surrounding the coup against Arbenz. In part, this is due to the rarity for the American education system to teach about the United States government’s involvement in Latin America beyond a few approved highlight-reel moments. This is further compounded by Americans seldom taking the time to learn about other cultures. And as governments are representative of the general population, in addition to the assumed exceptionalism of the United States, this has created a sense of institutionalized amnesia amongst policymakers. This willful amnesia has led to the forgetting of the actions of one administration by the next. This contrasts the experience in Latin America, where despite the large size of some nations, the interconnectedness is more apparent, and has created an atmosphere where it is harder to erase the collective memory. The preservation of memory in Latin American is further extended by the diaspora of political exiles. Amongst these exiles are the descendants of Jacobo Arbenz, who have worked to counter the mythmaking that has warped the American memory surrounding the 1954 coup against Arbenz. Furthermore, it is myths that make nations, and whoever controls a nation’s education controls its past, and thus a nation's future.

In the mythmaking of the United States, history has become a foreign land dripping in nostalgia and dualistic fantasy, siloing the American public until erasing all nuance. Thus, the past has become a land of the dead controlled by the minds of the living. In his work, The Past is a Foreign Country, David Lowenthal discusses how the past has become like a foreign country, a place that only exists in our memory and the collective illusion of what society believes it to be. In discussing how the past is a foreign country, Lowenthal tells us that the “past and future are alike inaccessible.”(3) However, it is by creating a shared memory that we develop the history of our world. This memory becomes distorted when some attempt to sanitize the past through rose-colored imagery that grows as we distance ourselves from past events. These disingenuous memories of history build until the average person has nothing more than a postcard representation of a past event. And just as postcards provide little to no reality of what a foreign country is like to a traveler, so to, do these historical postcards hide the ugly truths behind the past.

The lack of cultural understanding of both past and present leads to the othering of people, places, and events. And in turn, this makes foreign that which one would believe themselves to be most intimate with. Lowenthal reminds us that, “the miracle of life is cruelly circumscribed by birth and death; of the immensity of time before and after our own lives we experience nothing.”(4) By looking at the 1954 coup against President Jacobo Arbenz we develop an understanding of how Cold War fanaticism and corporate greed combined to distort the American memory of twentieth-century Guatemala; and how this distorted memory effects both nations today. To correct this memory, we will look at how the U.S. raised Arbenz from obscurity to become to the scourge of U.S. “national security”, how after serving his purpose he fell back into obscurity, and how long-standing American policy held greater responsibility for the action taken in Guatemala than any supposed threat from “Communism.” To accomplish this, we will look at how members of the United States government, the Guatemalan government, the former Soviet Union, the Arbenz family, scholars of foreign policy in Latin America, Latin Americans and Guatemalans remember Arbenz and the coup against him. Unfortunately, this all hinges on if they have been able to remember one of the most important events in modern Guatemalan history, or if they have developed a hole in their memory due to the manufactured narrative surrounding the Cold War.

Jacobo Arbenz was the son of a Swiss father and a Ladino mother.(5) Early in life, he had been an impoverished young man that sought to support himself with a military career, as was the most common way to gain social mobility in early twentieth-century Latin America. Unfortunately for Arbenz, he did not have the prerequisite contacts or qualifications to gain entrance to the Guatemalan Military Academy. It was through a chance meeting that he was able to gain sponsorship through none other than the President of Guatemala at the time, Jorge Ubico.(6) However, it would be Arbenz’s later participation in the 1944 Revolution that overthrew the Ubico regime, and his commitment to closing the wealth gap between the social elites and the majority of Guatemalans that brought the wrath of the United States government and business interests down on him.(7) This is what led President Dwight D. Eisenhower to authorize Operation PBSUCCESS, the Central Intelligence Agency's name for the 1954 coup against Arbenz.

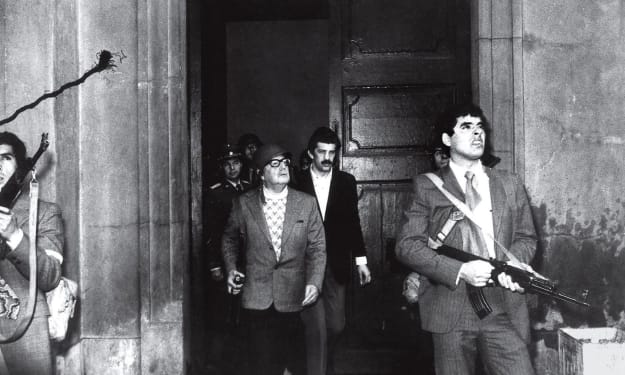

Ubico had ruled Guatemala in the American business-friendly fashion expected by the United States government during his thirteen-year reign. A coalition of military officers and Guatemalan businessmen led a revolution against Ubico in 1944. The three main leaders were Francisco Arana, Jorge Toriello, and Jacobo Arbenz.(8) Following the revolution, the new administration held the first free elections in Guatemala's history. This saw Juan Jose Arevalo become the first democratically elected President of Guatemala. Arevalo had been an exiled professor and proponent of “spiritual socialism.” Spiritual socialism focused on developing Guatemalan’s morality leading to their psychological liberation.(9) In contrast, Arbenz was most concerned with the liberation of his countrymen from the feudalistic system that crippled their economy. This was due to Arbenz’s view of Arevalo as an ineffectual leader.(10) It was during his early presidency that Arbenz’s intelligence and ability to network with those of other parties began to show.(11) This led to the implementation of Decree 900.27. As professor Piero Gleijeses discusses in his article, The Agrarian Reform of Jacobo Arbenz, the Guatemalan Senate passed Decree 900.27 on June 17, 1952, in response to pressure from Arbenz and public demonstrations in support of the bill.(12) The Decree announced:

that all uncultivated land in private estates of more than 672 acres would be expropriated; idle land in estates of between 224 and 672 acres would be expropriated only if less than two thirds of the estate was under cultivation; estates of less than 224 acres would not be affected. By contrast, the government owned Fincas Nacionales (130 large estates that produced a quarter of the country's coffee crop) would be entirely parceled out.(13)

Arbenz’s personality, intelligence, and selfless devotion to his people were in sharp contrast to those that would lead the coup against him.

One of those that led the coup against President Arbenz was the Ambassador to Guatemala, John Peurifoy. In this role, Peurifoy was serving the traditional role of American diplomats in Latin America. The traditional role of American ambassadors in Latin America often reflected more of a military-governorship that wore the face of a local dictator that was good for business interests and little else. President Juan Jose Arevalo in August 1945 gave a speech in opposition to this prevailing attitude in which he declared that “now begins the second phase of [World War II, for] our America should not consent to the existence in its lands of totalitarian regimes under a democratic disguise.”(14) This attitude had developed out of the U.S.’s interventionist policies towards the hemisphere following the adoption of the Monroe Doctrine and Roosevelt Corollary. These two policies had kept US troops employed by intervening in nearly every Central American and Caribbean nation since the closing of the Frontier in the 1890s. It was during this period that the U.S. pushed out the last remnants of European influence. After World War Two the Soviet Union became the new European specter that threatened the U.S.’s regional hegemony.

In this context, the ambassador would brand Arbenz as a crypto-Communist, an agent of the Soviet Union.(15) John Peurifoy had been with the U.S. diplomatic service since 1938. Before serving in Guatemala Peurifoy had served in Greece. According to Eisenhower, “He was familiar with the tactics of the Communists in Greece, where he had served. Peurifoy soon reached definite conclusions on the nature of the Arbenz government.”(16) Eisenhower was forgetting that Peurifoy had arrived in Greece after the Greek Civil War ended. However, Peurifoy had every reason to go along with this lie, as Senator Joseph McCarthy had been promoting a hardline anti-Communist stance in the State Department, due to suspected Communist infiltration.(17) In October 1954 the Executive Branch sent Peurifoy to elucidate its position on Arbenz to the Subcommittee on Latin America of the House Select Committee on Communist Aggression. At this hearing, he gave a sweltering list of qualifications that made Arbenz a Soviet plant. He began with,

It is my understanding, Mr. Chairman, that the purpose of your hearings is to determine:

1. Whether or not the government of President Arbenz was controlled and dominated by Communists.

2. Whether or not the Communists who dominate Guatemala were in turn directed from the Kremlin.

3. Whether or not the Communists from Guatemala actively intervened in the internal affairs of neighboring Latin American republics.

4. Whether or not this Communist conspiracy which centered in Guatemala represented a menace to the security of the United States.

My answer to all four of those is an unequivocal “yes.”(18)

However, the memories of his accused differ far from those of Peurifoy.

In the late 1990s, CNN made a documentary called Cold War, in which they interview several of those on the receiving end of Peurifoy’s accusations. According to Oleg Daroussenkov of the Communist Party Central Committee, “up until that time, we had viewed Latin America as a distant, exotic continent with which we had virtually no relations.”(19) Mister Daroussenkov’s memory of their influence on Guatemala gives legitimacy, as the Soviet government was still in a state of flux following the battles for succession after the death of Stalin in 1953. But none of this mattered in the malleable minds of the coup plotters.

Memory is as fickle as sands on a beach, while the beach always exists, the particulars shift often. When politicians, statesmen, and others with a public image to protect write their memoirs, it is often what goes unsaid that is most important. There is no better example of this than Eisenhower’s memoir, Mandate for Change. If there were no clearer indication of Eisenhower’s understanding of the world, or how important Guatemala was to him, the lack of mention of PBSUCCESS or discussion of Arbenz in his memoir is startling. Written about a decade after Eisenhower authorized the Central Intelligence Agency to conduct Operation PBSUCCESS, even the title Mandate for Change sets the tone of his book. Almost, every nation that was important to his tenure gets a map, from Korea to Taiwan, to Italy and Yugoslavia. But Guatemala is nearly absent, despite its purported importance as being the vanguard of a Soviet invasion of the Western Hemisphere.

Reflecting on Eisenhower’s memoir, a different image of this domineering president emerges. For in his memoir he appears to know what the real issues were in Latin America. He even wrote that:

we all realized that the fundamental problems of Latin America- which stem from lack of capital; overdependence on the sale of primary commodities; severe maldistribution of wealth; illiteracy, and poverty- would take a long time for nations themselves to correct even with all the outside help they deserved.(20)

One would be right in feeling confused about reading such a statement from the same man that authorized the overthrow of a president that was working to improve the material condition of his people by correcting the “severe maldistribution of wealth.”(21) And as tempting as it may be to blame the disconnect on Cold War paranoia following the Korean War, one must face the reality that in the minds of the Eisenhower administration any threat of Communism was nothing but a form of foreign aggression that was little better than outright military invasion.(22) According to Eisenhower himself, “the American republics wanted no Communist regime within their midst.”(23)

This mindset was not helped by Eisenhower’s recollection that Central America was a region where dictators maintained the governments, and this, in turn, fueled the resentment against the United States.(24) According to Eisenhower, the resentment against the United States was by uncontrolled Communist factions in these nations. In this, Eisenhower fails to remember events that were barely more than a generation removed from his administration. In his memoir, he neglects the memory of how the U.S. had come to dominate the Western hemisphere. Yet, one has to wonder whether this was due to Eisenhower’s willful ignorance of US-Latin American history of the early twentieth century, or if it had more to do with the man having never served outside of the United States before World War Two. For his contemporaries remembered U.S. involvement in Central America quite differently.

The short-lived memory of the American government is nothing but extraordinary, for within two decades the warnings of Smedley Butler were already forgotten when it came time to fight against the “Communist” threat. In his 1935 book, War is a Racket, Butler described a racket as:

something that is not what it seems to the majority of people. Only a small ‘inside’ group knows what it is about. It is conducted for the benefit of the very few at the expense of the many.(25)

Butler had served in nearly every U.S. invasion of a Latin American country from 1898 to 1915. Nothing demonstrates Butler’s definition of a racket more than the secrecy that surrounded the coup against Arbenz. For it would be more than three decades until the U.S. public had any idea of what occurred in 1954. The U.S. government was able to keep up the veneer until 1982, when Stephen C. Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer published their book, Bitter Fruit. This was the first glimpse the American public gained at the large disparity between the threat that Arbenz had posed and those not on the inner most rings of policy decision making. It was also one of the first looks at how corporations and the U.S. government worked together to maintain the prevailing economic system.

Unfortunately, the average American, past and present, is intentionally kept unaware of the unduly familiar relationship between those that hold government offices and those in large corporations. This has the effect of creating false or fleeting memories that restrict the American public from creating a memory to begin with. The official secrecy of the office which they hold further compounds this by protecting such officials from revealing their positions in said companies. Such was the case afforded to the Secretary of State, the Director of Central Intelligence, and the United States ambassador to the United Nations during the Eisenhower administration.(26) All of these men had either a professional or familial connection to the United Fruit Company.(27) This gives a different flavor to the recollection of “Arbenz's 'pet project'” of agrarian reform.(28) In this, Arbenz emerges as less of a dyed in the wool Communist, and more of a President that sought to correct the economic deficiencies in his country. This becomes clearer when one realizes that the basis for expropriating land from foreign corporations was Decree 900’s passage by the Guatemalan Senate, not a declaration given by President Arbenz. This was quite a different story from that which was being spun by Washington.

While often seen as mere entertainment, political cartoons provide some of the best ways of understanding what the media thought of politicians in their own time. These cartoons function as time travelling court jesters that communicate a comedic and emotional reaction to events that are often lost in journal and news articles. By straddling the differences between written and visual journalism, they create unique memories of their time. It is quite difficult to find any official memories about the coup against Arbenz written by either of the Dulles brothers. With this, one must surmise one of two realities concerning how the former Secretary of State and Director of Central Intelligence viewed their roles in this affair. Either they both lived the rest of their lives believing in what they had done, or they chose not to acknowledge the folly they had unleashed. Given the depiction of John Foster Dulles in many of the political cartoons at the time, the former appears more apparent. Herbert Block immortalized John Foster's arrogance in one of his cartoons from a 1956 edition of the Washington Post. The cartoon depicts Dulles pushing Uncle Sam, the paternalistic personification of the United States, towards a cliff labelled “War.”(29) John Foster Dulles's hawkish attitudes are further attested to in the speech he gave to The Tenth Inter-American Conference in March of 1954.(30) Dulles’s went as such,

This conference was shocked by the dastardly attack on members of the United States Congress by those who professed to be patriots. They may not themselves have been communists. But they had been subjected to the inflammatory influence of communism which avowedly uses extreme nationalism as one of its tools.(31)

The fact that such speeches are not well remembered in the tale of the Cold War zeitgeist speaks to the institutionalized amnesia in the United States.

Much of Dulles’s speech relied on hyperbolic rhetoric to incite and legitimize the U.S. action in Guatemala by passing a blanket resolution of hemispheric solidarity against Communistic influence.(32) A major part of this was Dulles’s overconfidence and arrogance in believing many of his own lies. Despite this, there were some that saw through the veil of hypocrisy. As Washington began weaving the tale of Arbenz’s supposed Communist leanings he went on the offensive. In March 1954 Arbenz assured reporters,

that the Soviet Union had not intervened, was not intervening and did not threaten to intervene in the internal affairs of Guatemala. He said that this was “contrary to what is happening to us among the ruling circles of other counties.(33)

Unfortunately, the vail would not be fully pierced for two decades, when Stephen Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer began their investigation into the coup against Arbenz.

Up until the late 1970s, the C.I.A. continued to deny having documents related to the coup. Yet even when the story of PBSUCCESS began to break in the early 1980s, the C.I.A. attempted to cover their tracks by destroying as many documents related to the operation as possible.(34) Steven Schlesinger recounted in a 1999 interview, that it was a lawsuit that he had filed via the Freedom of Information Act that had prevented the C.I.A. from destroying the documents, as their claim that the documents would harm national security was in effect an admission that they had the documents.(35) A part of the C.I.A.’s push back was due to its inability to cope with the shift in domestic and foreign cultural attitudes surrounding Communism, and the Cold War.(36) This created a situation where the C.I.A. was actively contradicting other parts of the Executive Branch.(37) This should not be a surprise, as Schlesinger noted in his 1997 article, “The C.I.A. Censors History,” “even back in the fifties, the C.I.A. felt it had a license to mislead a President.”(38) Despite their best attempts at covering their tracks, the Third World kept the memory of the chaos unleashed by Eisenhower Administration and the C.I.A. alive.

Famed Mexican painter Diego Rivera was one of the first Latin Americans to create a profound memory of the coup. The Arbenz family was still searching for a country that would take them in permanently when he created his mural commemorating the coup against Arbenz.(39) La Gloriosa Victoria, the name itself is a mockery of how the coup plotters viewed their actions. The mural's inclusion as part of the official C.I.A. history of the coup is particularly fascinating.(40) Despite the inclusion of the mural, historian Nicholas Cullather manages to only focus on the “main” actors of Dulles, Peurifoy, and Colonel Armas. The bulk of Guatemalans to do not appear to factor into the official C.I.A. history. Despite the C.I.A.'s amnesiac relationship with the painting's symbolism, the imagery would not be lost on Rivera’s main audience.

While Rivera certainly intended his painting to be for the world, the imagery he used invokes memories of early twentieth-century struggles. The mural forces one to draw their eyes from one side to the other. On the extreme right are Guatemalans, mainly children, locked in a prison cell. Immediately following them are the victims of the massacre that was sure to come after Arbenz’s downfall. Just outside the prison walls Guatemalan peasants are either wielding machetes against one another or are lying on the ground as the harvest of the slaughter. Continuing to pan left, we come to the priest who can only grimace as he delivers last rights to the product of the free market. The priest is invocative of the Catholic church’s propensity to look the other direction when faced with morally reprehensible governments.(41) Particularly troubling in the mural is child victims. One can see this as Rivera having a bleak outlook on Guatemala’s future. This is further cemented by the image of Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, the man that would succeed Arbenz. He stands in the middle of the painting shaking hands with John Foster Dulles as Dulles is paying him off. Ambassador Peurifoy flanks Dulles dressed in military-style clothing, as Director of Central Intelligence Alan Dulles whispers in his brother’s ear. Meanwhile, a cadre of Guatemalan military officers dressed in stereotypical fascist filed uniforms flank Armas. In this Rivera connects his painting to two unfortunate realities of U.S. foreign policy at the time.

Most Americans remember the United States of the late1930’s to mid-1940s as being fundamentally anti-fascist. However, time and propaganda have distorted this into a false memory. In fact, for much of the twentieth century the U.S. was not just comfortable with but often preferred to work with fascist governments, as they were often more open to U.S. economic policy.(42)

This is further reflected in two parts of La Gloriosa Victoria. This is first seen in the men surrounding Armas. All the men are wearing World War Two-era German uniforms. In particular, they are wearing Nazi-style helmets. The equipment carried by the soldier guarding the bananas and the workers provides a second example of the U.S. government's connection to fascistic regimes. The guard is carrying German guns while wearing an American style uniform. The portrayal of the soldier serves to link American interventionism and the comfort of American administrations with fascistic regimes. In showing the soldier this way, it also shows who was intervening in Guatemalan politics, as “U.S. imperialism has always kept Latin America as a backyard reserve, preventing free exchange with the rest of the world, and forbidding relations with the socialist countries.”(43) Of course none of this would be taking place without approval from President Eisenhower, who shows up in the painting in a peculiar way.

The painting depicts Eisenhower as nothing more than a face on a bomb held by John Foster Dulles. The image of the man behind the thrown controlling a strong general goes against the common portrayal of Eisenhower as a leading figure of the Greatest Generation. However, this is much closer to the reality that was Eisenhower’s administration. Eisenhower became president not from a deep-seated desire to continue to serve his country, but rather as the product of a concerted effort to “draft Eisenhower” conducted by both parties.(44) Yet, the average American remembers Eisenhower as a strong and capable president. This is more emblematic of a modern application of the old phrase “to the victor go the spoils”, except in this case the spoils are the right to be remembered in addition to the sovereignty and economic well-being of one’s nation.

The U.S. had long-held paternalistic attitudes towards Latin American states. It was this belief in the U.S.’s divine right to subjugate Latin America that drove Operation PBSUCCESS, rather than a crusade against Communism. As historian Alan McPherson tells us in his article, U.S. Interventions, and Occupations in Latin America,

Latin Americans could be forgiven for thinking. In the late 1940s, that U.S. intervention was dead. But U.S. policymakers were growing obsessed with a new global enemy-communism-and they assumed that Latin American were unable to resist its wiles.(45)

However, the ability of Arbenz and the Guatemalan government to force the United Fruit Company into compulsory arbitration directly contradicted this view.(46) It was this show of strength, and the backlash against Arbenz that created the strongest memory amongst future Latin American revolutionaries. In particular, it affected how Fidel Castro and Che Guevara reacted when the U.S. attempted to reestablish a friendly regime in Cuba following the Cuban Revolution. As Castro recollects in an interview from the late 1990s,

We couldn't think about the Cold War at that time, and besides we were naive. We really believed there was a certain international order. We believed in the existence of certain international principles. We believed that the sovereignty of nations would be respected.(47)

Nothing could be further from the truth, as the U.S. increased pressure on its despotic allies, it created a league of Latin American nations dedicated to sharing intelligence that would ferret out any suspected Communist.(48) This was the driving force behind the radical authoritarianism that rose in the wake of the Cuban Revolution.(49) This was authoritarianism born from the memory that if one did not have strong allies, then one risked American paternalistic care snuffing out one's revolution. Unfortunately for most of Latin America, one man’s authoritarian is another man’s liberator. And after Arbenz went into exile Guatemala fell to a roving band of Presidents until Miguel Ydigoras Fuentes took the reins.(50)

By reflecting their American counterparts, the Guatemalan government created a system for intentionally forgetting not just Arbenz, but also all socio-economic gains before the coup. This system of institutionalized amnesia in Guatemala made it convenient for even the Guatemalan President to pontificate against Communism to his U.S. audience, while having a less clear-cut past. Miguel Ydigoras Fuentes displays how he liked to remember himself as a staunch anti-communist. Yet, even his memory was faulty on this point. As he recounted in his official biography, My War with Communism, that during one conversation with the President at the time he was once accused of being a “Communist.” As he wrote of his conversation with President Ubico,

I boldly suggested to the President that truck drivers be allowed traveling expenses on the basis of the distance traveled, so much per kilometer. General Ubico, who was an impressive man, with a harsh and haughty air, looked me squarely in the eye and said: “So! You too are a Communist!” … Civil liberties were so restricted that it was not even possible to travel freely within the country.(51)

This reminds one of anthropologist Lesley Gill’s observation in her book, The School of the Americas: Military Training and Political Violence in the Americas, that the label of Communist was “an enormously elastic category that could accommodate almost any critic of the status quo.”(52) The status quos threatened by both the October Revolution and Arbenz was freedom of movement. In the time before the October Revolution and Arbenz, “freedom of enterprise was entirely relative and dependent on the will of the ‘General.’”(53) All regimes before Arbenz, and his predecessor Arevalo, placed a stranglehold on all forms of expression either spoken or written. While also ensuring that the lower classes were kept in a state of bond-slavery.(54) The Ubico regime accomplished the restriction on freedom of movement by two methods. One was the requirement of all laborers to carry a libreta (“pay book”) at all times under threat of arrest.(55) The other means was the militarization of even the most mundane of government offices, “including the post office, schools, and symphony orchestras.”(56) However, this form of government quite suited the relations of the United States government and their business partners, and thus they sought a man they could rely on.

In 1958, the C.I.A. found their man in General Miguel Ydigoras Fuentes. Fuentes took power in 1960, following a series of pseudo-elections.(57) As he recounts in his memoir, My War with Communism,

A former executive of the United Fruit Company, now retired, Mr. Walter Turnbull, came to see me with two gentlemen whom he introduced as agents of the C.I.A. They said that I was a popular figure in Guatemala, and they wanted to lend their assistance…(58)

Unfortunately, this was more mythmaking conducted on the behest of the C.I.A. For as soon as the coup against Arbenz had succeeded in the eyes of the U.S. government, then the Guatemalan government moved to erase him from the public record. This was only hampered by the fumbling and infighting by the series of generals attempting to take the Presidency in the intervening years between the fall of Arbenz and Fuentes. However, once the Right reestablished control, they would continue to deny Arbenz’s achievements for the next 57 years. While they tried to eradicate the memory of Arbenz from the official record, they could not extricate him from the people’s hearts.

In 2011, one of Arbenz’s grandchildren made a moving short documentary about the return of their grandfather’s body to his country. The documentary opens with the line, “If you could read my mind…”(59) A short portion of the song Bohemian Rhapsody by Queen accompanies the opening. The person that made this chose the portion of Bohemian Rhapsody where Queen sings the line,

Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?

Caught in a landslide, no escape from reality

Open your eyes, look up to the skies and see

I'm just a poor boy, I need no sympathy

Here the filmmaker is alluding to the surreal nature of what happened to their grandfather. Yet, at the same time, they are also alluding to the fantastical memory created to discredit the Arbenz regime. A fantasy that even the C.I.A. fed into during the Cold War, leading them to believe that Operation PBSUCCESS was a blueprint for future operations. This blueprint hypothesis led the U.S. to abject failure in its attempt to counteract the Cuban Revolution in April 1961.(60) The weaving of the successful coup fantasy was only a part of the C.I.A.’s delusion and self-aggrandizement. As seen in the Arbenz family documentary, Jacobo Arbenz was a well-loved and seen as a legitimately democratic leader by most Guatemalans. However, as the documentary and history show, this democracy was in a very fragile state at that point in Guatemala.(61) The list of candidates shown on the voting form in the documentary shows numerous candidates, even Arbenz’s future nemesis Miguel Ydigoras Fuentes makes the list.(62) Some of the more important pictures shown in the video are those of the peaceful transfer of power between the Arevalo and Arbenz administrations.(63) This is one of the more important memories the video could show, as it belies the U.S.’s usual notion that this only happens in U.S. style democracies. This mindset is due mainly to the underlying feeling of exceptionalism in the United States, and over time this exceptionalism has led many in the U.S. to dehumanize people from other countries.

It is the humanizing effect of the video that is most important in changing the memory of Arbenz. Society often builds up historical figures until they are nothing more than a caricature. This is where the true value of this video comes in, as the author gives the audience a view into the private world of the Arbenz family. After the official photographs, come the family photos. Interestingly the filmmaker starts with a photo from the repatriation of Arbenz’s body in 1995.(64) The first photograph shows his casket in a funeral home, surrounded by his family, with his silver coffin draped in the Guatemalan flag. The next photo is of the Guatemalan people carrying his casket through the streets. This photo is important as it shows that despite the U.S.’s unwillingness to recognize its role in the coup, Guatemalans would remember for them.

As journalist Larry Rohter recounts of his time in Guatemala during the repatriation of Arbenz’s body, “the former President's tomb here, a simple white pyramid just to the right of the main entrance of the General Cemetery, has quickly become a magnet for Guatemalans who seek an alternative to the four decades of right-wing rule that have followed.”(65) The story told by Rohter is one of an intergenerational memory of Arbenz. Gerardo Davila, who was 93 at the time, demonstrates this when he speaks to his great-granddaughter, Ana Lucia Bran about the effect of Arbenz on the Guatemalan people. Davila tells his great-granddaughter, “there has never been another like him, with such great ideals… Since his fall, there has been no progress in this country, only stagnation."(66) Some like Matias Perez, 83, went as far as to declare, "I loved him very much."(67) The Guatemalan government gave the Arbenz family a formal apology following the repatriation of Arbenz’s body. Following these steps, Guatemala’s history books were rewritten to reflect “Arbenz’s positive influence on the country.”(68) In 2011 the Guatemalan government renamed the national highway in Arbenz's honor. Additionally, his official was biography was rewritten and the government created a new educational system to train government employees to take into account the needs of indigenous people. This was a 180-degree turn from the government’s history of genocidal actions against the Mayan population.(69) The treatment of Arbenz in the modern era sharply contrasts the memory of Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, who's tomb inscription reads, "To the Liberator of Guatemala, Anti-Communist Martyr," the passage of time has not been so kind.(70) There is no better demonstration of the intentional forgetting of Castillo Armas in Guatemala than the fact that while his grave is right next to Arbenz’s, the flowers have wilted along with his legacy.(71) Who could blame people for their anger against the man that plunged Guatemala into a 35-year civil war, which resulted in more than 100,000 dead.(72)

It is an unfortunate reality that every cause has its detractors. We see this in the memory of Lionel Otero, who saw the coup against Arbenz's as a “‘liberation,’ because he said communism was a real threat to the country.”(73) Everyone feels entitled to their opinion, no matter how misinformed they may be. This is an unfortunate downside of the American system of democracy that has become a symptomatic problem within the United States political culture where fear drives policy, even if policymakers over exaggerate the threat to the American public.(74) This has combined with a system that rewards this behavior, and further encouraging this attitude in subsequent generations. Later U.S. presidents demonstrate this in how they spoke about Latin America.

The unspoken rule of institutionalizing amnesia towards policy in Latin America began with the Kennedy administration. John Fitzgerald Kennedy became President of the United States of America on January 20, 1961. And with the Presidency he inherited an atmosphere of hostility towards the U.S. in Latin America.(75) This situation was not helped when in his Inaugural Address he seemed to be talking out of both sides of his mouth to the observant listener. For in his address he speaks about how man holds in his hands the power to abolish poverty.(76) The hypocrisy of his pledge throws one off when looking back at his speech. As Kennedy told the crowd,

to our sister republics south of our border, we offer a special pledge--to convert our good words into good deeds--in a new alliance for progress--to assist free men and free governments in casting off the chains of poverty.(77)

The practice of having a public-facing policy that was contradictory to the realpolitik became the modus operandi employed in Latin America. This drinking of the corporate Kool-Aid had infected every administration until it became the prevailing zeitgeist in the U.S. government. Nothing shows this more than a speech in which President Ronald Reagan gave to the Soviet Union in 1987, “‘Let us move toward a world in which all people are at least free to determine their own destiny.’”(78) Reagan gave this speech while his administration was simultaneously supporting Right-wing paramilitaries in most of Central America.(79) The U.S.’s support of these paramilitaries has been the greatest legacy from the coup against Arbenz.

In the late 1970’s, French philosopher Michele Foucault developed his Boomerang theory.(80) This is the theory that societies that are victims of colonization will return to their former colonizers, bringing with them all of the deleterious effects of colonizing.(81) While the U.S. never formally colonized Central America, it is now beginning to feel the effects of what it has sewn in the region over the past 65 years. We see this as immigration from Central America has increased precipitously following the end of the Guatemalan Civil War, and in the wake of devastating economic failure.(82) This has increased both racial and economic tensions within the United States, while the American public is continuously fed lies that it is Latin Americans that are coming to take their jobs. In this, we see the continuance of the institutionalized amnesia needed to corral the American population and redirect their focus away from large corporations that benefit from both the offshoring of their jobs and the cheap labor provided by new immigrants that are willing to accept lower wages.

In closing, the introduction of non-state actors in the foreign policy of the United States was a major factor in the coup against President Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala in 1954. In 1954 the United Fruit company approached two of its former associates, John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles, to assist them in counteracting the effects of Decree 900. In his intent to free Guatemalans from their feudalistic economy to create a more capitalistic state, Arbenz threatened U.S. business interests in the impoverished nation. This was despite United Fruits' declining profitability from their banana plantations in Guatemala.(83) The United States government declared President Arbenz a “Communist” and an agent of the Soviet Union due to his support land reforms. This declaration was due mainly to the Dulles brother’s roles as the Secretary of State and the Director of Central Intelligence, and as board members for Sullivan and Cromwell, the law firm representing the United Fruit Company. Due to the privileges afforded to them by their positions, they were able to avoid public scrutiny for their actions. This combined with Cold War fanaticism led to the institutionalized practice of forgetting U.S. intelligence and covert action failures. And this, in turn fed the myth that the U.S. was on the right side of history. Thus further fueling the American public’s belief that their government could do nothing wrong in fighting the “Communists.” However, laws of official secrecy have clouded the memory of the American public.

The trouble with memory is the impossibility to observe all things. Even when historians attempt to write with accuracy, limitations force us to leave things behind due to lack of space or lack relevance. Lowenthal reflects on this issue in his book, The Past is a Foreign Country, “many seem less concerned to find a past than to yearn for it, eager not so much to relive a fancied long-ago as to collect its relics and celebrate its virtues.”(84) Despite the growing ability to record our lives, we will forever miss what is outside of the frame. And just as meddling in the affairs of foreign countries, altering the past would cause consequences beyond comprehension. It would be impossible to reshape the past without destroying the present. And thus, we face an ugly truth. The past, with its pestilence and ignorance, is still a necessary part of who we are. While we wish to believe the past is behind us, it is here in the present, puppeteering the lives of the living and making decisions for those that are unconscious of its effects.

Thank you for reading my work. If you enjoyed this story, there’s more below. Please hit the like and subscribe button, you can follow me on Twitter @AtomicHistorian, and if you want to help me create more content, please consider leaving a tip or become a pledged subscriber.

Other works by this author:

In text citations:

1. Gleijeses, Piero, “The Death of Francisco Arana: A Turning Point in the Guatemalan Revolution,” Journal of Latin American Studies, October 1990, 549-550.

2. De Leon, Sergio, “Guatemalans Divided 50 Years After Coup”, Associated Press, June 17, 2004.

3. Lowenthal, David, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 1.

4. Ibid., 1.

5. “Swiss Family Arbenz.” TIME Magazine, January 17, 1955.

6. “Battle of the Backyard.” TIME Magazine, June 28, 1954.

7. De Leon, Sergio, “Guatemalans Divided 50 Years After Coup”, Associated Press, June 17, 2004.

8. Schlesinger, Stephen and Stephen Kinzer. Bitter Fruit: The Untold Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books, 1982.

9. Arevalo, Juan Jose, Greg Grandin, Deborah Levenson, and Elizabeth Oglesby (eds), “A New Guatemala”, The Guatemala Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durhman: Duke University Press, 2011.

10. “Battle of the Backyard.” TIME Magazine, June 28, 1954.

11. Ibid.

12. Gleijeses, Piero, “The Agrarian Reform of Jacobo Arbenz,” Journal of Latin American Studies, Cambridge University Press, October 1989, 453-80.

13. Ibid., 459-460.

14. Moulton, Aaron, Conflicts between Caribbean Basin Dictators and Democracies, 1944-1959, History of the Caribbean, Diplomatic History, August 2016

15. Memorandum: Selection of Individuals for disposal by Junta Group, March 31, 1954.

16. Eisenhower, Dwight D., Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, Double Day &Company, Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, 422.

17. Flora, Lewis, "Ambassador Extraordinary: John Peurifoy: Washington's Spokesman in the Guatemalan Struggle Characteristically Wears no Homburg. He is a Man of Action rather than a Diplomat. Ambassador Extraordinary." New York Times, 18 July 1954.

18. Eisenhower, Dwight D., Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, Double Day &Company, Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963,422-423

19. Mitchell, Pat, and Jeremey Isaacs, Season1, Episode 18 “Backyard”, Cold War, CNN. 1998.

20. Eisenhower, Dwight D., Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, Double Day &Company, Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, 421

21. Ibid., 421.

22. Ibid., 421.

23. Ibid., 421

24. Ibid., 421.

25. Butler, Smedley, War is a Racket, New York, Round Table Press, Inc., 1935, 2

26. Mitchell, Pat, and Jeremey Isaacs, Season1, Episode 18 “Backyard”, Cold War, CNN. 1998.

27. Shulman, Jack. “Cuba Won’t Become Another Guatemala, Declares Arbenz.” August 28, 1960.

28. Gleijeses, Piero, “The Agrarian Reform of Jacobo Arbenz,” Journal of Latin American Studies, Cambridge University Press, October 1989, 456

29. Hoopes, Townsend. The Devil and John Foster Dulles. Boston: Little, Brown, 1973.

30. "Aid to Arbenz Pledged: Three Guatemalan Parties Issue Manifesto of Support." New York Times, 15 June 1954.

31. Mitchell, Pat, and Jeremey Isaacs, Season1, Episode 18 “Backyard”, Cold War, CNN. 1998.

32. Bracker, Milton, “Arbenz Attacks Foreign Critics”, The New York Times, March 2, 1954, 10.

33. Ibid., 10.

34. Schlesinger, Stephen., “The C.I.A. Censors History.” Nation. 1997, 20–22.

35. Schlesinger, Stephen, Richard Nuccio, and Jennifer Schirmer. "Preserving Bitter Fruit." Harvard International Review 21, no. 4 (Fall, 1999) ,24-29.

36. Ibid., 24-29.

37. Ibid., 24-29.

38. Schlesinger, Stephen., “The C.I.A. Censors History.” Nation. 1997, 20–22.

39. “Visit to the Old Country.” TIME Magazine. January 3, 1955, 30.

40. Cullather, Nicholas, “Operation PBSUCCESS: The United States and Guatemala 1952-1954. History Staff, Center for the Study of Intelligence,” Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC, 1994.

41. Arellano, Mariano Rossell, Greg Grandin, Deborah Levenson, and Elizabeth Oglesby (eds), “Enemies of Christ,” The Guatemala Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durhman: Duke University Press, 2011

42. Henderson, Alex. “7 Fascist Regimes America Enthusiastically Supported.” 10 February 2015.

43. Memorandum: Selection of Individuals for disposal by Junta Group, March 31, 1954.

44. Immerman, Richard H. John Foster Dulles: Piety, Pragmatism, and Power in U.S. Foreign Policy, Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources, 1999, 38-39

45. McPherson, Alan, US Interventions and Occupations in Latin America, History of the Caribbean, History of Central America, History of Mexico, Diplomatic History, March 2019

46. Bracker, Milton, “Arbenz Attacks Foreign Critics”, The New York Times, March 2, 1954, 10

47. Mitchell, Pat, and Jeremey Isaacs, Season1, Episode 18 “Backyard”, Cold War, CNN. 1998.

48. Moulton, Aaron, Conflicts between Caribbean Basin Dictators and Democracies, 1944-1959, History of the Caribbean, Diplomatic History, August 2016.

49. McPherson, Alan, US Interventions and Occupations in Latin America, History of the Caribbean, History of Central America, History of Mexico, Diplomatic History, March 2019

50. Kennedy, Paul P., “Arbenz is Deposed”, New York Times, June 28, 1954.

51. Fuentes, Miguel Ydigoras, My War with Communism, as told to Mario Rosenthal, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963, 36.

52. Gill, Lesley, The School of the Americas: Military Training and Political Violence in the Americas, Duke University Press, 2004, 10.

53. Fuentes, Miguel Ydigoras, My War with Communism, as told to Mario Rosenthal, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963, 36.

54. Ibid., 36.

55. McCreery, David, Debt Servitude in Rural Guatemala, 1876-1936, The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 63, No. 4 (November 1983), pp. 735-759, Duke University Press.

56. Arbenz Family, The Real Story, Guatemala Spring, “The Real Story, Who was Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán? Why is Arbenz relevant to History and Guatemalaspring.org?”, 2011.

57. De Leon, Sergio, “Guatemalans Divided 50 Years After Coup”, Associated Press, June 17, 2004.

58. Fuentes, Miguel Ydigoras, My War with Communism, as told to Mario Rosenthal, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963, 49-50.

59. Arbenz family, Tribute to Jacobo Arbenz Guzman and Guatemala's history. Harvard University, David Rockefeller, Latin American Studies, public forum on October 7, 2011.

60. Mitchell, Pat, and Jeremey Isaacs, Season1, Episode 18 “Backyard”, Cold War, CNN. 1998.

61. Arbenz family, Tribute to Jacobo Arbenz Guzman and Guatemala's history. Harvard University, David Rockefeller, Latin American Studies, public forum on October 7, 2011.

62. Ibid.

63. Ibid.

64. Rohter, Larry, “Left's Hero Is Home (but Then, He's Long Dead)”, New York Times, December 6, 1995.

65. Ibid.

66. Ibid.

67. Ibid.

68. “Guatemalan Government Issues Official Apology to Deposed Former President Jacobo Arbenz’s Family for Human Rights Violations- 57 Years Later: Arbenz Family and Other Notables to Give Formal Statements on Thursday”, PR Newswire, New York, NY, September 29, 2011.

69. Schivone, Gabriel M., Why are Guatemalans seeking asylum? U.S. policy is to blame, 23 Dec 2018.

70. Rohter, Larry, “Left's Hero Is Home (but Then, He's Long Dead)”, New York Times, December 6, 1995.

71. Ibid.

72. Ibid.

73. De Leon, Sergio, “Guatemalans Divided 50 Years After Coup”, Associated Press, June 17, 2004.

74. Ibid.

75. Mitchell, Pat, and Jeremey Isaacs, Season1, Episode 18 “Backyard”, Cold War, CNN. 1998.

76. Transcript of President John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address, 1961.

77. Ibid.

78. Fischer, Fritz, The Memory Hole: The US History Curriculum Under Siege, Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc., 2014.

79. Mitchell, Pat, and Jeremey Isaacs, Season1, Episode 18 “Backyard”, Cold War, CNN. 1998.

80. Graham, Stephen. “Foucault’s Boomerang: The New Military Urbanism.” 14 February 2013.

81. Ibid.

82. Schivone, Gabriel M., Why are Guatemalans seeking asylum? US policy is to blame, 23 Dec 2018.

83. Position of the United Fruit Company, June 23, 1953.

84. Lowenthal, David, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 6.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

1. Memorandum: Selection of Individuals for disposal by Junta Group, March 31, 1954.

2. Position of the United Fruit Company, June 23, 1953.

3. "Aid to Arbenz Pledged: Three Guatemalan Parties Issue Manifesto of Support." New York Times, 15 June 1954.

4. “Battle of the Backyard.” TIME Magazine, June 28, 1954.

5. “Swiss Family Arbenz.” TIME Magazine, January 17, 1955.

6. “Visit to the Old Country.” TIME Magazine. January 3, 1955.

7. Arbenz Family, The Real Story, Guatemala Spring, “The Real Story, Who was Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán? Why is Arbenz relevant to History and Guatemalaspring.org?”, 2011.

8. Arbenz family, Tribute to Jacobo Arbenz Guzman and Guatemala's history. Harvard University, David Rockefeller, Latin American Studies, public forum on October 7, 2011.

9. Arellano, Mariano Rossell, Greg Grandin, Deborah Levenson, and Elizabeth Oglesby (eds), “Enemies of Christ,” The Guatemala Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durhman: Duke University Press, 2011.

10. Arevalo, Juan Jose, Greg Grandin, Deborah Levenson, and Elizabeth Oglesby (eds), “A New Guatemala”, The Guatemala Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durhman: Duke University Press, 2011.

11. Bracker, Milton, “Arbenz Attacks Foreign Critics”, The New York Times, March 2, 1954.

12. Butler, Smedley, War is a Racket, New York, Round Table Press, Inc., 1935.

13. Flora, Lewis, "Ambassador Extraordinary: John Peurifoy: Washington's Spokesman in the Guatemalan Struggle Characteristically Wears no Homburg. He is a Man of Action rather than a Diplomat. Ambassador Extraordinary." New York Times, 18 July 1954.

14. Hoopes, Townsend. The Devil and John Foster Dulles. Boston: Little, Brown, 1973.

15. Kennedy, Paul P., “Arbenz is Deposed”, New York Times, June 28, 1954.

16. Mitchell, Pat, and Jeremey Isaacs, Season1, Episode 18 “Backyard”, Cold War, CNN. 1998.

17. Schlesinger, Stephen and Stephen Kinzer. Bitter Fruit: The Untold Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books, 1982.

18. Transcript of President John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address, 1961.

Secondary Sources

1. “Guatemalan Government Issues Official Apology to Deposed Former President Jacobo Arbenz’s Family for Human Rights Violations- 57 Years Later: Arbenz Family and Other Notables to Give Formal Statements on Thursday”, PR Newswire, New York, NY, September 29, 2011.

2. Cullather, Nicholas, “Operation PBSUCCESS: The United States and Guatemala 1952-1954. History Staff, Center for the Study of Intelligence,” Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC, 1994.

3. De Leon, Sergio, “Guatemalans Divided 50 Years After Coup”, Associated Press, June 17, 2004.

4. Eisenhower, Dwight D., Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, Double Day &Company, Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963.

5. Ferreira, Roberto Garcia. "The CIA and Jacobo Arbenz: History of a Disinformation Campaign.” Journal of Third World Studies 25, no. 2 (Fall, 2008): 59-81.

6. Fischer, Fritz, The Memory Hole: The US History Curriculum Under Siege, Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc., 2014.

7. Fuentes, Miguel Ydigoras, My War with Communism, as told to Mario Rosenthal, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963.

8. Gill, Lesley, The School of the Americas: Military Training and Political Violence in the Americas, Duke University Press, 2004.

9. Gleijeses, Piero, “The Agrarian Reform of Jacobo Arbenz,” Journal of Latin American Studies, Cambridge University Press, October 1989.

10. Gleijeses, Piero, “The Death of Francisco Arana: A Turning Point in the Guatemalan Revolution,” Journal of Latin American Studies, October 1990.

11. Graham, Stephen. “Foucault’s Boomerang: The New Military Urbanism.” 14 February 2013.

12. Grim, Ryan, “You’re Thinking About Fidel Castro All Wrong: He Wasn’t Operating in a Vacuum”, Huffington Post, November 18, 2016

13. Henderson, Alex. “7 Fascist Regimes America Enthusiastically Supported.” 10 February 2015.

14. Immerman, Richard H., John Foster Dulles: Piety, Pragmatism, and Power in U.S. Foreign Policy, Wilmington, Del. : Scholarly Resources, 1999.

15. Lowenthal, David, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

16. McCreery, David, Debt Servitude in Rural Guatemala, 1876-1936, The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 63, No. 4 (November 1983), pp. 735-759, Duke University Press.

17. McPherson, Alan, US Interventions and Occupations in Latin America, History of the Caribbean, History of Central America, History of Mexico, Diplomatic History, March 2019.

18. Moulton, Aaron, Conflicts between Caribbean Basin Dictators and Democracies, 1944-1959, History of the Caribbean, Diplomatic History, August 2016.

19. Rohter, Larry, “Left's Hero Is Home (but Then, He's Long Dead)”, New York Times, December 6, 1995.

20. Schivone, Gabriel M., Why are Guatemalans seeking asylum? US policy is to blame, 23 Dec 2018.

21. Schlesinger, Stephen., “The C.I.A. Censors History.” Nation. 1997.

22. Schlesinger, Stephen, Richard Nuccio, and Jennifer Schirmer. "Preserving Bitter Fruit." Harvard International Review 21, no. 4 (Fall, 1999).

23. Shulman, Jack. “Cuba Won’t Become Another Guatemala, Declares Arbenz.” August 28, 1960.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (1)

Excellent article. Thank you for sharing this with us & helping to dispel just a little of the fog surrounding our historical & political amnesia.