What is a Slip of The Mind?

If you are confused or having trouble remembering names, don't jump to conclusions. It may just be a slip of the mind.

I am always confusing my children’s names. There are three of them. At first I thought I was suffering from early dementia. Literally I would have to say all three names before I got it right. Their names had slipped my mind. Mostly when they were relentlessly asking me the same thing over and over again until they got their way.

We have all endured the humiliation of calling someone we know by the wrong name, felt the frustration of a phrase on the tip of our tongue, and known the bewilderment of not recognizing a familiar word when it slips your mind. Language offers a running commentary on our mental state. A pileup of little errors leaves behind a trace of fear that as we age we may be losing our mind. Through studies of people with specific brain injuries, neuroscientists have begun to map the communities of brain cells that serve language; in particular, they have located the lost and found department for words. From this guide, we can see how the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon might arise, what it means, and how to deal with it.

Unfamiliar Territory

Those with damage to the back left side of the brain's frontal lobe often can't spontaneously find what words they want or name an object they see without a “prompt," such as the first sound of the word or a common expression that includes the word. They might come up with the right number of syllables and approximate the sound—for example, substituting birch, when they mean beach—or use a word in the right category, like hot for cold, ball for bat.

After damage to the back of the left temporal lobe, people may not recall the name of an object they can describe—but they will choose the correct item from a group of objects when given the name. It is the words that slip the mind, not the pictures. They may be able to name things in one category, like pieces of furniture, but not name animals or fruits. It's as if they can't gain access to the dictionary of words stored among their brain cells.

Still others can't connect a word to a common object, as if they have lost their knowledge about words as symbols for objects. In these instances, the brain is injured where the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes join. If there is a roadblock in the connections between this junction and one of the lobes, they may not come up with the name upon seeing an object, but they will after feeling it, or vice versa. Or, like some dyslexic people, they can write a word dictated to them, but moments later can't read it.

Searching for the Unsearchable

These areas of the brain interact in marvelous ways to give us word recall and other language skills, but the links are delicate and easily upset. At least one in five of the two million people who suffer a stroke or serious head injury each year are left with some variety of aphasia, difficulty in comprehending and expressing language. In Alzheimer's disease, the tragic decline of intellect is always accompanied by progressive problems in word-finding. In the early stages of this brain-cell degeneration, people will talk around the word they want and the context of their speech becomes increasingly trivial.

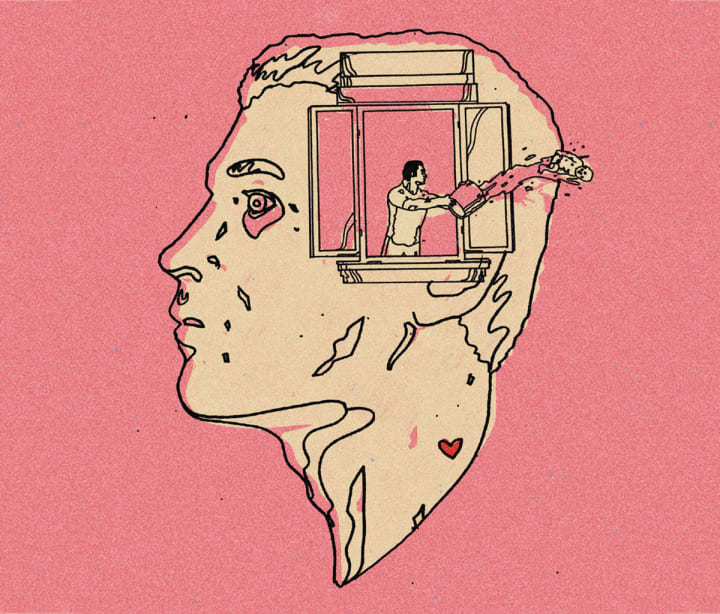

But the almost automatic way we find words falters much more commonly because something far less perilous than a stroke or Alzheimer's interrupts the smooth commerce of messages between brain cells. Such insults can include anxiety, depression, pain, fever, any acute or chronic illness, inadequate sleep, hunger, minor head bonks, alcohol, or any drug that gets into the brain (tranquilizers and sleeping pills)– and, most often, too many thoughts or drifting concentration. The brain cells that effortlessly mold language become intoxicated, overburdened, or lose their focus on the task at hand, creating temporary holes in the language pathways and leaving a word on the tip of the tongue.

The Brain Replays Thoughts

A physician should be consulted after a few days of constant difficulty in word-finding. But most of us can overcome occasional blunders by taking advantage of the many roads that access the brain's language centers. When you cannot say the word, try to visualize the object or associate it with a vivid past experience. For instance, if you can't recall the name of a car part, think of the last time you changed a tire or worked on the engine. You might also start a sentence that the Word would typically complete or list other words that fall into the same category.

When all else fails, stop trying so hard to find the word. A subconscious search often continues like a beacon scanning the dark for a familiar object. The brain seems to replay unfinished thoughts along its pathways until the answer comes, even while the mind is occupied by another matter. That is a slip of the mind. When the word finally turns up, we can give a tiny sigh of relief about the health of what makes us especially human.

About the Creator

Wendy Weedler

Lives in Washington D.C. Has been part of the legalization movement for decades.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.