Understanding the Aging Brain

By understanding the aging brain, you can combat illnesses and promote brain health.

My grandfather, who lived to be ninety-four, always insisted that the secret of a long and lucid life was to keep active, interested, and busy. When he was about 40, he wrote a letter to his local newspaper expressing some trenchant opinions about the current state of the economy. Fifty-four years later, just before he died, he was still sharing his opinion through social media outlets like Facebook about dogs, Notre Dame football, millennials, and all the myriad other subjects that caught his far-ranging attention. He may have been ninety-four, but his mind had remained supple and young.

What made my grandfather so fortunate? Why, for many other people, does living a very long life carry the penalty of pronounced mental decline? As unprecedented numbers of people attain extreme longevity in the decades to come, the answers to such questions will take on even more pressing importance.

Searching for the answers, researchers have learned a great deal about what happens to the human brain as it grows older, how we might possibly influence those changes, and even how we might restore the brain to health after it has been diseased or damaged. One thing we know about the aging brain is that it shrinks. From a peak of billions (some say trillions) of brain cells in our teens and early twenties, we lose cells at the rate of several thousand a day.

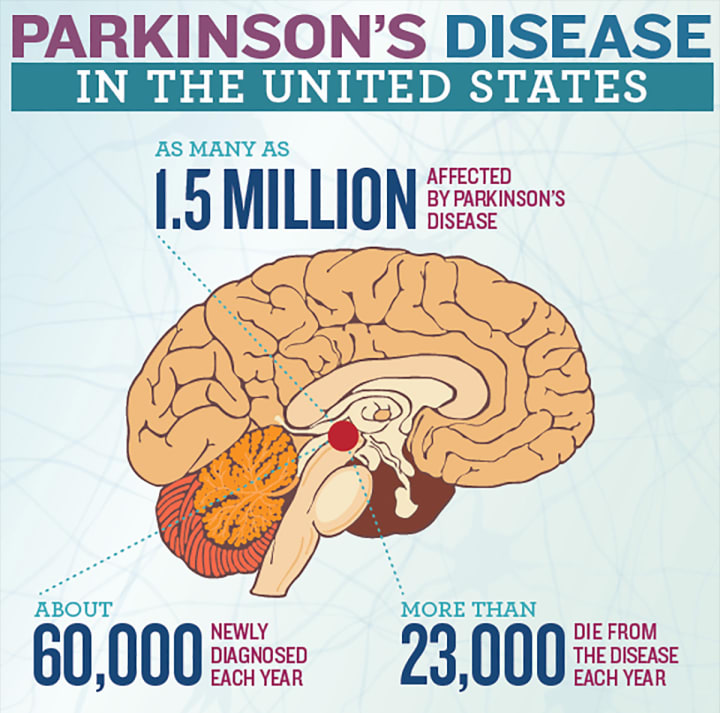

The decrease in brain size is evident on autopsy or through a brain scan. "People have actually counted and tracked the number of cells lost," says Stephen H. Peroutka, M.D., Ph.D., and a specialist in Parkinson's disease. What they have discovered is that some parts of the brain lose more cells than others. In the substantia nigra, the portion of the brain that controls movement and is involved in Parkinson's disease, we start off with 600,000 cells, says Peroutka. By the age of eighty, most people are down to 100,000. In some cases, the number dips even lower, and this sometimes happens to younger people—individuals in their forties. Such a drastic falling-off of substantia nigra cells brings on Parkinson's, with its characteristic disabling symptoms of body rigidity, stooped posture, and shuffling gait.

Image via Healthy Holistic Living

Parkinson's Disease

Just about every eighty-year-old shows some mild, fleeting Parkinson's-like symptoms, just as most show some of the forgetfulness associated with Alzheimer's disease. But for the majority, impairments are seldom a problem. Most people retain enough cells well into their eighties for relatively normal function. Still, there are millions of Alzheimer's patients in the United States, and some researchers consider this the tip of the iceberg. They place the number closer to four million—and rising, as the population ages. Estimates of the number of people with Parkinson's disease range up to one million, with about 60,000 being diagnosed each year. Thus it is these two diseases that are most associated with the deteriorating brain, and against which the greatest research offensive has been directed.

Fortunately for Parkinson's patients, some remarkable breakthroughs in both science and surgery have brought new hope. Surgeons in Sweden and Mexico have pioneered an operation in which cells are removed from the patient's adrenal gland and transplanted into the brain. There, they transform into nerve cells and produce dopamine, the chemical that is manufactured in the substantia nigra and is depleted because of cell loss in Parkinson's disease.

More than 250 such operations have been performed worldwide, with mixed results. The Mexican neurosurgeon Ignacio Madrazo, M.D., claims 80 percent improvement in some patients and has shown before-and-after videotapes at conferences to support his claim. However, American surgeons who have performed the operation report only mild to moderate improvement.

Nonetheless, any improvement is noteworthy. Thus, many scientists agree with Lars Olson, professor of histology at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, whose time dedicated to basic research laid the groundwork for the operation. Olson and other researchers believe that transplants of either adrenal or fetal cells hold great promise, and the major hurdle now is the refinement of transplantation techniques.

The work of Olson and others is part of a larger revolution that is reshaping science's view of the human brain. For decades, conventional wisdom insisted that the number of brain cells was fixed at birth. The brain lost cells throughout life, it was said, and had no way of replacing them or repairing itself. The idea of transplanting cells or tinkering with the brain's chemistry was considered the stuff of science fiction—"associated," says neurologist Robert J. Joynt, M.D., "with castles in Transylvania, brains in jars, and operations by the dark of the moon." However, a number of landmark experiments have laid that view to rest.

In 1969, Godfrey Raisman of Cambridge University showed that damaged nerve cells sprouted new fibers, and this phenomenon of "collateral sprouting" was further developed by psycho-biologists Carl Cotman and Gary Lynch at the University of California at Irvine. In 1984, Cotman scooped out a cavity in a test animal's brain, then delayed a week before transplanting nerve tissue into the wound. Cotman found that the graft-host connection was much stronger than when the transplant was done immediately. He attributed the difference to a "wound factor" secreted by the damaged brain to stimulate healing. Since then, scientists have found clues that the brain may be armed with a battery of similar neurotrophic (nerve-cell-nourishing) factors, perhaps numbering in the dozens or even hundreds.

Such discoveries have given scientists a glimpse of a remarkable and exciting system of brain repair, which might be manipulated to slow or alter the process of brain aging, and possibly even to put things right if they go awry. Even that stubborn, puzzling, and tragic scourge of the older population— Alzheimer's disease—might be corrected and controlled.

Image via PrimeSource

Alzheimer's Disease

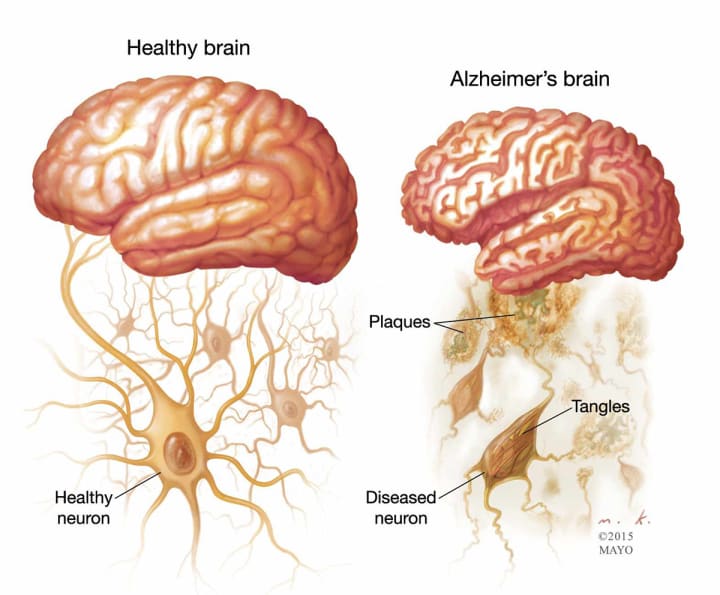

Alzheimer's disease is believed to be caused by any combination of environmental, genetic, and lifestyle factors that affect the brain over time. But the sad symptoms are familiar: loss of memory, especially for recent events, as well as disorientation, confusion, and dementia. On autopsy, the brain of an Alzheimer's victim shows distinctive changes. Like other "old brains," it is smaller, but it is also overgrown with disorderly fibers, called neurofibrillary tangles, and clumps, or plaques, of a little-understood protein called amyloid. These changes also occur in the brains of normal older persons, but to a lesser degree. It is not known whether the changes bring on the symptoms of Alzheimer's or whether both result from some unknown common cause.

Cotman offers a possible explanation when he suggests that Alzheimer's disease represents the sprouting phenomenon gone wild—the brain reaching out to make new connections between cells, working to replace or bypass damaged cells so industriously that its connections finally end up horribly tangled. To compound the problem, the few remaining healthy cells break down from the strain of seeking help in all directions and carrying the load for their diseased fellows. “It’s like the senior faculty member whom everybody asks, "Can I have more money? Why can't you teach four more courses?" says Cotman, not wholly tongue in cheek. "And he can't do it because he's sprouted about as many connections as he's got, and he'd just collapse from the weight."

The possibility that Alzheimer's is related to the neurotrophic factors leads to the possibility that the disease could be treated with medication. One prominent candidate in such treatment might be nerve growth factor (NGF), a substance known to influence the higher brain centers, which are involved in such functions as reasoning and memory.

NGF For Alzheimer's

The most exciting reports—with tremendous potential for Alzheimer's disease—come from the neurobiological laboratory of Anders Björklund. Here, at one of the most respected universities in Europe, Björklund has been using NGF to improve the memory of rats. Björklund places older rats who have begun to show signs of age-related forgetfulness into what is known as a Morris water maze. This tank is filled with a milky fluid that conceals a submerged platform. The rats swim until they locate the submerged platform and can pull themselves to safety.

To watch the rats' performance, as did Lund last year, is to get a fascinating lesson in the importance of a healthy brain and sound memory. The rats are of the same age and species, chosen from the same litter. All are nearing the end of their life span. Day after day, one by one, they are slipped into the tank. But one group has been infused with NGF. The other has not. The NGF rats swim almost unerringly to the underwater platform, remembering it from past experience. The non-NGF rats, forgetful and bewildered, swim in circles and usually find the platform only by an accidental collision. Even when the platform is removed, the treated rats swim quickly to where they know it should be.

Although there would seem to be an obvious parallel between the forgetful old rats and the failing memory of Alzheimer's disease, Björklund is careful not to say so. The rats do not have Alzheimer's disease; “the application is only by analogy," he says. Since we do not know what causes Alzheimer's disease, it cannot be reproduced in animals.

Image via 18 Grains

Mind and Body Health

Keeping weight and blood pressure down promotes brain health, too. Hypertension is a major cause of stroke, whose devastation of the brain kills or disables over a half million persons a year. In almost all cases, hypertension can be controlled by drugs. Controlling weight helps to control blood pressure, as well.

In a sense, what you eat goes to your head, because several dietary-deficiency diseases attack the nervous system. Nerve and muscle degeneration is a sign of beriberi, caused by lack of vitamin B1; memory loss results from pernicious anemia, caused by lack of vitamin B12. Both vitamins are found in liver and other organ meats; B1 in grains and cereals, green vegetables, and nuts. There may also be a brain-health reason to eat organic foods. One theory suggests that the cause of Parkinson's disease may be modern chemicals, since the disease was not recorded until after the Industrial Revolution. Moreover, several studies have shown Parkinson's to be more prevalent in agricultural areas where large amounts of chemicals are used.

But one of the most potent mental life-extenders may come from the mind itself. My grandfather attributed his nine healthy decades of life and lucidity to using his brain and letting people know what he was thinking. Current research suggests that Grandfather may have been right. Some of the most intriguing evidence that an active brain stays young into advanced old age came from the laboratory of Marian Diamond, Ph.D., professor of integrative biology at the University of California at Berkeley. Diamond found that rats who are stimulated by what she called "toys"— swings, ladders, wheels, and treadmills—develop bigger brains than their cage mates and maintain brain function longer. Even if they were only spectators, watching younger, more frolicsome animals at play, their brains benefitted. On average they were still alert and curious at three years of age—the human equivalent of 90 years.

The evidence from Diamond's lab and others suggests that "exercising" the mind keeps it fit and youthful, just as physical exercise keeps the body in shape. As for humans, Diamond says, "If you don't use it, you lose it." My vociferous, inquisitive, prolifically letter-writing nonagenarian grandfather would have been the first to agree.

About the Creator

Alicia Springer

Mother of two. Personal trainer. Fitness is about determination, not age.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.