Color and Sound

Meditations on the Human Condition

The world around us is alive with color and sound. Often, there is too much information to absorb, and our minds become overwhelmed with data. Every individual has a different tolerance level for data overload. Some individuals are only comfortable when immersed in color and sound, while others prefer silence and monochrome. There are also individuals who drift between immersion and stillness, sometimes favoring one, sometimes the other.

The Awaodori is a festival dance that has been practiced and performed in some parts of Japan for centuries. Zen Buddhism, one of the principle religions of Japan, places an extremely high value on silence. Buddhist monks will often take vows of silence that will last for decades. Some Buddhist monasteries prohibit all forms of sound within their compounds, except for the drone of insects or the singing of birds. This dichotomy within Japanese culture is not a paradox. It arises out of the natural differences between individual humans. Neither the clamor of the Awaodori, nor the stillness of a Buddhist monastery is appropriate for everyone. There is no greater value in one over the other. Differences between individuals are neither something to be celebrated, nor something to be scorned. It is our differences that define us individually, and allow us each to play a different role in the great drama that is life.

There is a story told in Hinduism about a wise and learned Brahmin who was the most valued advisor to a particular king. He served his king from the time he finished his studies of the ancient texts until the day the king died and was replaced by his son. The son did not value the wisdom of the old Brahmin, so he sent him into retirement. As a parting gift, in recognition of his long service to the kingdom, the son gave the Brahmin a rare, beautiful, and very valuable vase. It was the only item of any worth the Brahmin had ever owned and he cherished it greatly.

One night, a few years after his retirement, a thief broke into the Brahmin’s home. As he reached for the vase the old man awoke. The two stared into each other eyes for a few moments. The thief spoke first, “If you try to stop me, I will kill you. If you report me to the magistrate my sons will find you and kill you.”

“But this vase is my only treasure,” replied the Brahmin, “if you take it from me what use will I have for my life?”

“Does your life mean so little you would sacrifice it for a vase?”

“You misunderstand me. I will not try to stop you from taking the vase. I just want you to know that when you leave here you are not taking a simple vase. You are taking my heart and soul with you and I will be devastated.”

The thief looked into the watery eyes of the old Brahmin. The Brahmin looked into the desperate eyes of the thief. For a moment, each felt the other’s pain and each knew the other’s heart. Then the thief slowly backed out through the door and the old Brahmin laid back down to sleep. The thief went on to sell the vase and feed his family while that night the Brahmin died in his sleep and went on to his next life.

The first time I heard this story, I thought it was a story about accepting fate and forgiving wrongdoing. Now, decades later, I realize the story is much more complex. It plays many of life’s dichotomies against one another without offering any additional commentary on the good or bad of each. Unlike an Aesop’s fable or a Biblical proverb, there is no overriding moral theme being presented. The purpose of the story is to remind us that we each go through life surrounded by different conditions, different situations, and under different pressures. We each make individual choices to confront or accept the challenges that life throws at us. We each play out our role in accordance with our internal reality, even when that internal reality has little or no relation to the one surrounding us. Our differences neither raise us up to kingship nor carry us down to thievery. King, Brahmin, and thief each play a different role in the greater drama that is life itself. The color and noise of our life shapes us, but our choices define us.

The beauty of the vase given to the Brahmin, the cacophony of Awaodori, the power of a new king, and even the desperation of a thief, shapes the internal reality of each individual, even as both the story and the festival shaped my understanding of the world I live in. Without these rich experiences, our internal reality can become so detached from the external one that we lose all touch with both. Insanity is the result of a schism so great between the internal world and the external world that the individual can no longer function effectively either within their own mind or within the greater world. Everything collapses and the individual either withdraws completely, lashes out violently, or takes their own life.

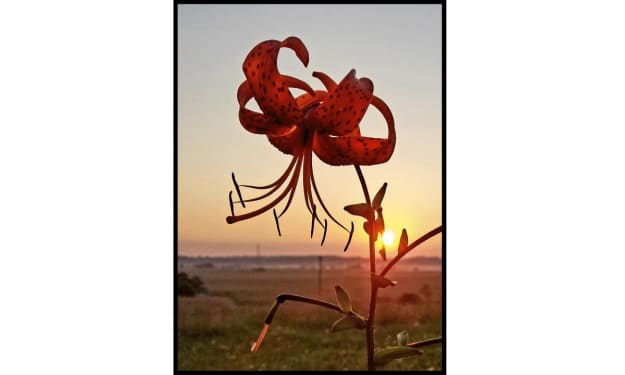

Color and sound connect us to the world, preserve our sanity, and shape our inner world, regardless of how much or how little we can tolerate. Even a Buddhist monastery devoted to silence must allow the droning of insects and singing of birds. These simple flashes of color and sound keep the monks grounded in the real world while their silent meditations allow them to explore their internal world.

I cannot define your tolerance for color and noise, and you cannot define mine. Instead, the key is recognizing that you and I exist within a shared reality, regardless of the state of our internal world. I have no right to impose my color and noise onto you, and you have no right to impose your color and noise onto me. However, when we come together, and compare our internal worlds, magic happens. Your color and noise shapes my internal world, while my color and noise shapes yours, and we both come away stronger, saner, and better equipped for whatever challenges the next day brings.

Color and sound, the internal and the external, everything has merit at some point to some individual. (Even though there are some individuals without hearing or without sight who cannot experience both color and sound). The only real enemy is disdain, because it is disdain alone which prevents an individual from those new experiences which are vital to growth, maturity, and eventually, wisdom.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.