The food legacy of a Holocaust survivor

Driven by his family history, Tibor Rosenstein is preserving Jewish-Hungarian cuisine through his Budapest restaurant, which has become a bucket list destination for food lovers.

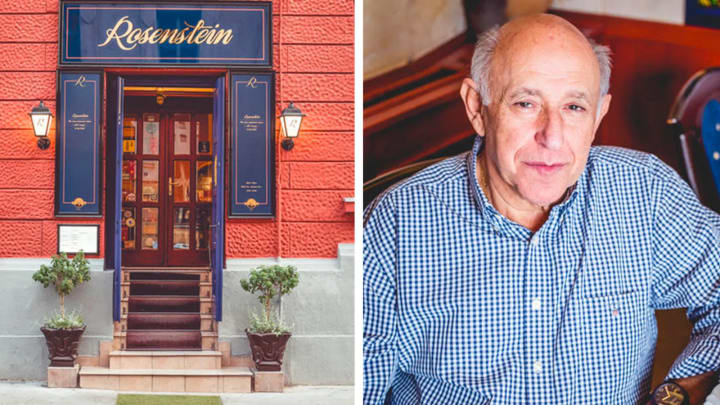

A mere block from Budapest's mammoth Keleti railway station sits Tibor Rosenstein's eponymous restaurant. The entrance comes off a quiet, unassuming residential corner far from the city's traditional culinary hubs. But like a temple, Rosenstein Restaurant stands alone as a monument to historical Jewish-Hungarian cuisine – drawing celebrities, television personalities and Jewish gastronomic globetrotters eager for a taste of the past.

"My personal cuisine and my dishes are traditional Hungarian-Jewish cuisine," said Rosenstein. This includes goose sausage and cholent, the traditional Jewish Sabbath stew left to cook overnight. Rosenstein's secret ingredient is ground paprika – perhaps the most beloved spice in all Hungarian cuisine.

An estimated 100,000 Jews remained in Budapest following Soviet liberation on 13 February 1945. Many families who stayed in the country relegated their Jewish heritage as a trivial aspect of their identity, leaving children to discover it only later in life. Today, the community is growing once again, primarily in the historic Jewish quarter surrounding the famous Dohány Synagogue, one of the largest synagogues in the world. Jewish restaurants, primarily kosher ones, have since sprung up in the neighbourhood, including most recently the city's first and only fast food kosher establishment, Kosher MeatUp. Rosenstein's is unique in the city for its obvious Jewish backbone.

Not that the restaurant is stuck in the past, replaying an old formula without ever adapting. Soon it'll have its own kosher coffee roaster to go along with its existing selection of kosher beers – the logo of which features a stencil of Rosenstein's charismatic grin topped with a yarmulke (a kippah or skullcap). The pandemic prevented him from publishing a cookbook for the restaurant's 25th anniversary, but plans are underway to release one in honour of the 30th anniversary in 2025.

Suffice it to say, Rosenstein isn't slowing down any time soon.

"I keep the fire alive through my dishes, or through welcoming and serving a large number of Jewish guests coming from abroad," he said, something he credits in part to his appearance in a 2017 episode of Andrew Zimmern's Bizarre Foods.

It's hard to imagine Rosenstein's horrific early years when basking in the glow of his ear-to-ear grin. Now 79, Rosenstein was a little boy when World War Two stormed through Budapest and the Soviet Union's Red Army liberated the city. Tragically, both his parents were murdered at Auschwitz, leaving him to be raised by his two surviving grandmothers.

It was a tough, meagre life in those early years after the war. Rosenstein and his family had to make the most of what they had, especially when it came to food.

She told me I should become a cook so that I would always have something to eat

"I used to help my grandmother with the cooking, and I really enjoyed it," he said. "She told me I should become a cook so that I would always have something to eat."

The young Rosenstein quickly became responsible for important kitchen tasks. One of them was to take the chickens from the market to the shochet (a person certified under Jewish religious law to slaughter an animal) to perform a kosher slaughter. That's not to say that they kept kosher all the time. Rosenstein said their financial situation didn’t allow them to buy the right ingredients at the time to keep kosher. His family wasn’t particularly religious anyhow. But it gave birth to his grandmother's favourite saying, "All the good things are kosher!"

It's a sentiment Rosenstein continued to live by throughout his culinary career, from interning at the Grand Hotel on Budapest's Margaret Island to serving as the head chef at Kispipa for 10 years starting in 1979.

As much as he enjoyed and was appreciative of his time working in different kitchens, his lifelong dream was to open his own restaurant. He finally did so in 1996, the humble Rosenstein Restaurant, tucked away from the fray with an approachable elegance that makes you feel like you're at your grandparent's house. Despite its unremarkable location, Rosenstein has spent the last two and a half decades cooking Hungarian-Jewish cuisine and growing a stellar word-of-mouth reputation. It explains how Rosenstein got his arm around the likes of Robert De Niro and Helen Mirren in photos adorning the wall. But perhaps more importantly, Rosenstein Restaurant has become a bucket list destination for Jewish food lovers thanks to its preservation of the traditional cuisine.

There are the classic staples, like chicken paprikash and matzo ball soup made with coarsely ground matzo from Israel. Then there are the dishes usually only found in history books, like roast leg of goose, and no shortage of offal recipes – such as sour lung stew with bread dumplings or cooked bone marrow on toast with pickled and fresh garlic – that prove the old adage of Jewish ancestors using every last bit of the animal.

Eszter Rubin is a Budapest-based, Jewish-Hungarian author and food writer who feels right at home when she dines at Rosenstein's and is equally drawn by the ambiance and the menu. "Rosenstein's restaurant makes me feel like I am in a traditional Jewish setting," said Rubin. "There's a wonderful mix of modern and innovative cuisine."

In 2014, Rosenstein distilled his family recipes and cooking ethos into The Rosenstein Cookbook – itself surely to become an important marker of Jewish-Hungarian cuisine. The cover, featuring a full plate of glistening, light-brown fried goose fat cracklings falling over one another, is hardly the colourful, bespoke dish of most cookbook covers and Instagram posts these days. But that's not Rosenstein's story.

"I included all those recipes in this special cookbook that have accompanied me in my life so far and have been part of my family traditions; or are dear to my heart for some reason," he wrote in the introduction.

It's not on the menu at Rosenstein but ask and you shall receive

Many of the recipes, and much of the menu, are recognisable to anyone who's read about traditional Jewish-Hungarian cuisine or had it passed down through their family. But thanks to Rosenstein, restaurant guests and home cooks can taste unique familial touches, like the sweet matzo ball with prunes, ground walnuts and honey. It's not on the menu at Rosenstein but ask and you shall receive.

"Yes, of course," he said when asked if they'll make the sweet matzo ball at the restaurant. "If it is ordered by a guest, we'll be pleased to prepare it for them."

András Koerner is a culinary historian and good friend of Rosenstein. His new book, Early Jewish Cookbooks, is a seven-essay volume that looks at the history of Hungarian Jewish gastronomy through its cookbooks.

A couple of decades after surviving the war and the Holocaust, Koerner moved to and raised his family in New York City. But he maintained close ties to his native Hungary and eventually became interested in writing about the cultural and culinary traditions of Hungarian Jews – traditions he didn't grow up with in his assimilated family.

This intellectual interest eventually led him to Rosenstein. Although Koerner had previously dined at Rosenstein, the two first met while cooking at a food show in New York 15 years ago. They quickly bonded over their shared passion for remembering the traditions of their ancestors.

Koerner went on to research and write books in hopes of preserving the memory of these traditions. In 2019, he published his award-winning tome, Jewish Cuisine in Hungary. The book reconstructs the culinary culture of pre-Holocaust Hungarian Jewry. An example included in the book shows the faded and worn cover of a family collection of recipes from around 1925. The collection comes from a woman named Mrs Ármin Neubauer – or Nádas, to use the Hungarian surname she adopted.

The Neubauer recipe collection is significant, Koerner writes, in that it shows the degree to which her family had assimilated to non-Jewish Hungarian culture with dishes made of rabbit meat – prohibited by kashrut (Jewish dietary laws). He adds that the collection is worthy of note not just because of its desserts, rich choice of soups, appetisers, main courses, vegetable dishes, salads and even homemade ear drops to combat hearing loss, but because of who owned it, Neubauer's grandson, Tibor Rosenstein – the owner and chef of what Koerner calls "one of the best restaurants in Budapest today".

Koerner said that he and Rosenstein enjoy discussing the importance of preserving an exceptional calibre for traditional Hungarian cooking, as well as Jewish food in general. He laments that many Budapest restaurants ignore their local culinary heritage in favour of chasing the latest craze in modern, international cuisine.

"For example, few restaurants sell traditional vegetable dishes – like creamed spinach, green beans in sweet and sour sauce or stuffed cabbage, which used to be mainstays of Hungarian and Jewish-Hungarian cuisine – since they are less profitable for the restaurants than fancy, fashionable dishes," said Koerner. "Some other 'rustic' dishes, like calf lungs or tripe pörkölt (a Hungarian stew with boneless meat, sweet paprika and vegetables), are also hard to find elsewhere. Tibor and I are very much interested in keeping carefully prepared versions of such simple dishes available."

In that spirit, Rosenstein offers a traditional vegetable plate every Monday as a special alongside other types of classic dishes, like calf lungs, tripe pörkölt and stuffed cabbage. Of course, in addition to these homely recipes, he also features elegant examples of traditional Hungarian cuisine, such as various courses with venison or fresh porcini. This is why Koerner believes that what Rosenstein offers Budapest's culinary scene is unlike anything else you can get in the city.

"In my opinion, his main contribution is keeping traditional Hungarian and Jewish-Hungarian cuisine alive, and to maintain very high standards of it."

It's the sweet burden of my origins and the everlasting loving memories of my grandmothers

Pushing 80 years old, Rosenstein is still a regular in the kitchen even as he slowly hands the reins over to his son, Róbert. The young Rosenstein is coming up with his own spins on the menu, like goose rillettes or stuffed goose neck with barley risotto.

Although there may be new faces in the kitchen, his grandchildren included, there's little doubt that Rosenstein will continue to be motivated to preserve the legacy of Jewish-Hungarian cuisine in Budapest.

"It's the sweet burden of my origins and the everlasting loving memories of my grandmothers," he said. "I respect them wholeheartedly."

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.