Unpopular Opinion:The Death Penalty Needs to be Suspended

Those most often put to death are those we understand the least about

What began as a public event soon became more private as executions were moved from outdoor gathering spaces to within prison walls. The death penalty has been in use in the United States since the mid-1600s. Early criminals were often put to death in front of jeering crowds who celebrated the act of execution. But the morbid desire to see people being killed was not diminished once executions were removed from public spaces. Crowds of people still clamored to gain entry to the exclusive events. The more publicized the crime, the more well-attended the execution.

Thus two camps of people have been established: those who revel in the deaths of criminals and those who find the entire process revolting. There are those who show up on execution day, cheering and shouting upon the news that the wrong-doer has been killed. The others, such as myself, watch those people on television, wondering what they are missing. Does it feel justified to kill the killer? Despite the fact that the person took a life, another life is being taken upon such execution.

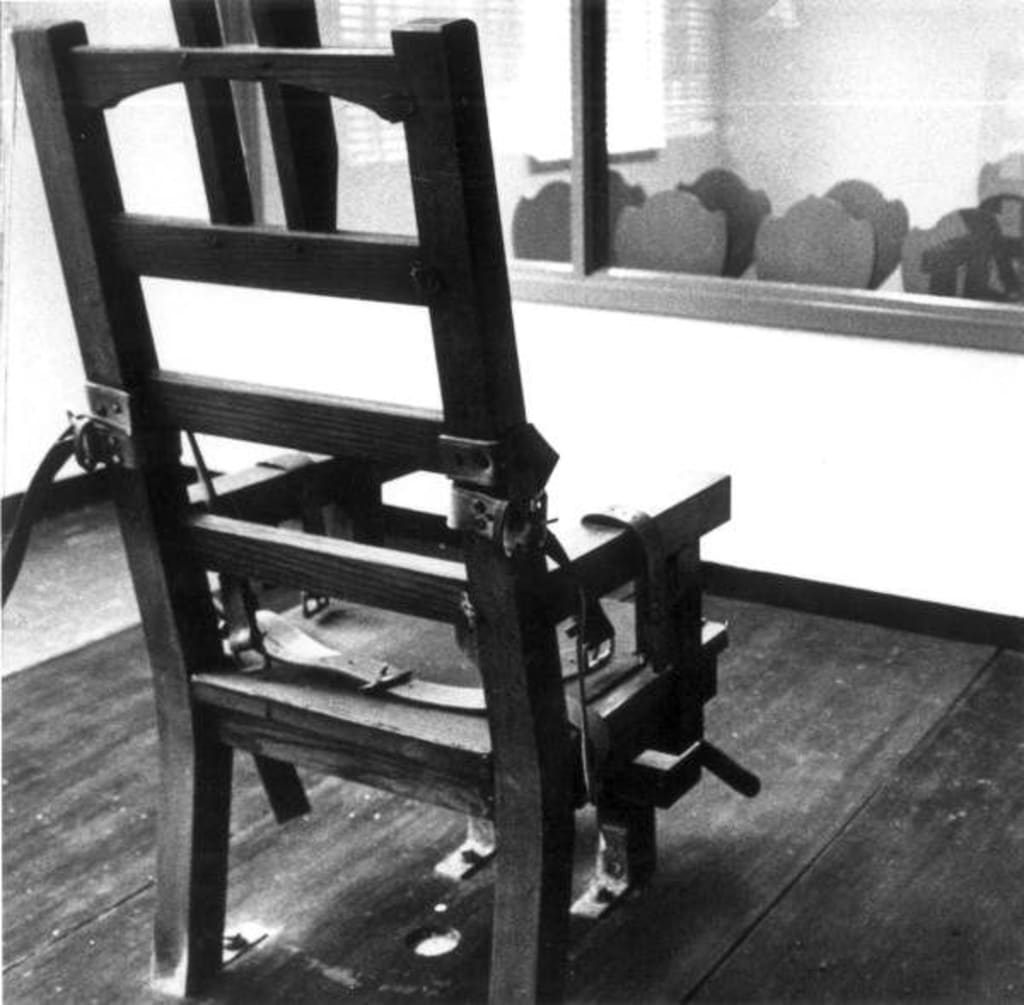

The realization of such blatant hypocrisy struck me as I was watching the final episode of Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes on Netflix. In the episode, Bundy is sentenced to death for the murders of countless women around the United States. On January 24, 1989, Bundy was finally executed in "Old Sparky," a lighthearted nickname given to a cold-hearted device: the electric chair at Florida State Prison.

I thought I would be on the side of those who were excited to see such a callous murderer meet his fate. But upon hearing the hoots and hollers of onlookers adorning "Burn Bundy" and "Fry-Day" t-shirts, I felt physically sick. Such reaction to the death of another human felt so unsympathetic and, truthfully, just plain wrong. Were not those watching and cheering just as callous as Bundy had been? I shared my sentiment with my roommate at the time, who agreed with me but rationalized that we were in the minority.

So, why did I care?

I could not fully understand my broad stance on capital punishment until I understood what bothered me about Bundy's execution specifically, that being: the State of Florida killed a man whose condition was not completely understood. It would be a stretch to say that I sympathize with Ted Bundy; I am fully aware that such heinous crimes are unacceptable. However, the misunderstanding of criminal psychopathology makes such executions equally unacceptable.

I continued feeling this way as I studied more and more cases of executed multiple-murderers. John Wayne Gacy, Gary Heidnik, Aileen Wuornos, among many others, all put to death for crimes which many of us feel uncomfortable even talking about. All killers who we view less as people and more as monsters.

And then it hit me: by dehumanizing these murderers, we are more easily able to do away with them. We see them as animals rather than as people, and are therefore able to see their execution as a favor to society.

By killing people we do not understand, our societies are regressing. Our fear of things we do not understand, usually by choice, perpetuates a flawed narrative which insists that murderers should be completely erased, despite our continued confusion regarding violent crime. Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, Aileen Wuornos, and Gary Heidnik all did things that any person could have done, given the proper circumstances (ie. nature plus nurture in the most deadly combination). But because we are so afraid to admit that they were people, we are more apt to throw them away. We would rather not think about them, make them disappear, and pretend they never existed in the first place. Unfortunately, violent crime is likely never going to disappear completely, so wouldn't it be in our best interest to learn something from those convicted of murder?

What We Can Learn From Killers Like Bundy

Violent offenders such as Ted Bundy can teach us a great deal, not only about our criminal justice system, but about the personality traits of those who linger outside the bounds of societal normalcy. Interest in psychopathy has gained traction over the past several decades, with violent psychopaths being a topic of particular fascination for psychologists, psychiatrists, and even the FBI.

But although so many are interested in psychopathy as a general concept, so few actually understand it. Psychopathy is most frequently characterized by reduced empathy, as well as antisocial behavior. Psychopaths are not always violent offenders, but those who do become violent are more likely to re-offend than the general population. Psychopathy is often measured by the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, first introduced by Robert Hare in the 1970s. The checklist comprises twenty traits which have been linked to psychopathic personalities, including shallow affect, grandiose sense of self-worth, and impulsivity. Individuals are scored on each trait, receiving either a 0, 1, or 2. If an individual scores thirty or more, they are considered a psychopathic personality.

Psychopathy is not something that happens overnight. It is cultivated during a person's upbringing and usually involves some sort of trauma during the formative early years. Today, it is believed by many that psychopathy is a combination of nature and nurture. People with psychopathy show brain scans different from non-psychopathic individuals. But the violent psychopaths are those whose upbringings were less-than-ideal. Preemptive treatment is the long-term goal in studies of psychopathy. The condition needs to be fully understood and targeted before violent acts are committed.

Ted Bundy fit the profile of a violent psychopathic personality to a tee. During his childhood, his mother pretended to be his sister to hide the fact that Ted was illegitimate. He was promiscuous, often dating several women at once. He was charming and egotistical, which made it easy to convince people to trust him. His grandiose sense of self-worth made him positive that he would never be caught. When he was caught, he escaped. Twice. He constantly denied having committed the crimes for which he was accused, despite the evidence that was piling up day by day.

Prior to his execution, Bundy attempted to trade confessions for time. When he finally admitted to a few of the crimes, he blamed violent pornography for his inspiration to kill. He knew he was doing wrong, but he could not stop. Every time he would fight off the impulse, it would come back with a vengeance. But then, he was electrocuted, and we are left wondering how many women he actually killed. The number has never been confirmed, and police are still unsure which states Bundy may have entered after his second escape. Not only could we have potentially learned about more unknown victims, but we could have further understood the mind of one of America's most notorious psychopaths.

When these people are killed, a great injustice is served to those in the mental health field. Those we put to death are the ones we still do not fully understand. And those who cheer on execution day are no better than the people they seek to destroy. It is important to study why and how violent offenders are able to commit such gruesome crimes, without feeling a shred of remorse. But first we need to view them as people, rather than as monsters.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.