Gymnastics is an Abusive Sport

My experience as a child gymnast and Olympic-hopeful.

My parents enrolled me in a gymnastics class at the age of five. An earnest desire on their part to support my growth and development quickly became the backdrop to my most traumatic experiences as a child.

By the time I was seven, I was on a competitive team. Plucked from the “fun” class, I was told that I was special and different and talented. I was also the perfect age to compete in the 2000 Olympics, if I was lucky.

The training of a child gymnast is like a never-ending, army boot camp. For 25 hours a week, young girls are screamed at, body-shamed, and pushed far beyond their physical and emotional limits. This, we are told, is how we become great. I now wonder if this treatment is a required course in gymnastics coaching school, as it seemed to be standard practice among the dozen or so coaches I had throughout my career.

Looking back, I wonder why I didn’t just tell my parents I wanted to quit. I hated not being able to play with my friends after school because I had to go to practice. I hated being screamed at and insulted by grown men. I hated the pressure to go far beyond my comfort zone and ignore all of my physical and emotional boundaries. But most of all, I hated what was done to my body.

The assessment days were the worst. Hours of physical tests were meant to measure our progress in strength and flexibility. As young girls, we were told to line up on the floor and get into our splits. Coaches would work in pairs. One would lift our front leg off the ground, hyper-extending it, while the other one, ignoring the tears running down our faces, would use a measuring tape to see how many inches they could lift our legs off the ground. The higher, the better.

During one such exercise, I asked one of my coaches to talk me through the pain. His response? “Sure, let’s talk about how your floor routine sucks.” A pretty standard response, I’m not sure what else I was expecting. This same coach once told me that he would compete with other coaches to see how many girls they could make cry in a day. I suspect he often won.

During one practice, I spent most of it trying to hide a spot of blood that had mysteriously appeared in the crotch of my light-lavender leotard. I didn’t realize until adulthood that I had torn my hymen during practice. I was eight.

Memories of blood dripping down my forearm while on the bars. I had a quarter-sized blister, which was common. My coach took out a pair of scissors and cut the dead skin off my hand, while I cupped the puddle of blood in my palm. He taped up the gaping wound, told me to put my dirty, chalk-covered grips back on and suck it up. We heard that term a lot.

It wasn’t until very recently that I could recognize this behavior as abusive. If you listen to the stories of survivors of childhood abuse, it is not uncommon for it to occur in plain sight of parents, and the community. Gymnastics was no different. Parents were groomed to believe their children were special, and gymnastics was an opportunity for brighter futures. The Olympics was a dream, as were college scholarships. And gymnasts were manipulated to believe that this was our one and only shot at greatness. So loving parents watched from the sidelines as their daughters cried in pain while grown men pulled their legs apart. It was for our own good, we were all told.

Leaving an abusive relationship is complicated for adults, and incredibly confusing for a child. By the time I was twelve, gymnastics was a part of my identity. I was the kid who could do flips on the playground, and my self-worth was deeply wrapped up in that. I had given the majority of my childhood over to this sport and I wasn’t even sure why, or how this happened.

Heading into middle school, my subconscious was screaming to get the hell out of there. If I couldn't control what was being done to my body by others, I would take control of what I would do to my own body. I remember being in my backyard standing on a ledge. It was only a few feet off the ground, but I realized that if I jumped off in just the right way, I could injure myself enough to be pulled out. Eventually, it worked. When I showed up to practice with an ankle brace, I was told to suck it up.

In my next attempt, I gave myself a sunburn so severe that my skin blistered.

Suck it up.

In my final, subconscious cry for help, I kid you not, I took poison ivy leaves and rubbed them all over my face and neck. And although I spent most of that summer dipping my face in cold milk, trying to soothe my swollen, itchy skin, I was glad, because I was finally free of gymnastics.

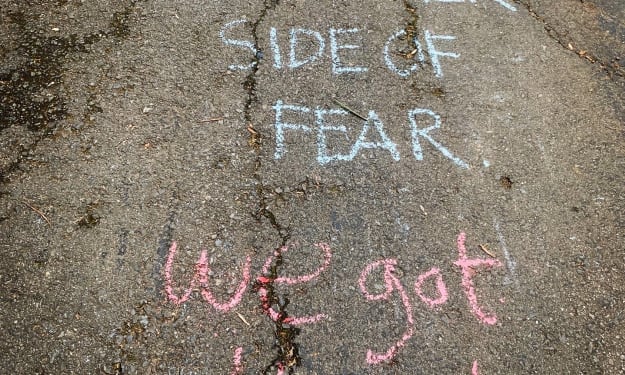

Being a competitive gymnast as a child was a traumatic experience. And while I do not view myself as a victim, I realize now that the sport was, and still is, an abusive one. At such a young age, I saw self-harm as my only way out, and in many ways, it was. So, to my inner child, who just wanted to play outside with her friends, I want you to know that it wasn’t your fault. You did everything you could and I’m so proud of you. To my parents, I know gymnastics took its toll on you, thank you for listening and pulling me out. And to the parents of gymnasts, I implore you to please listen to your children. Not just their words, but their actions and feelings. Ask them the hard questions that you may not like the answers to. Let them know they have a choice.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.