Consciousness Bound

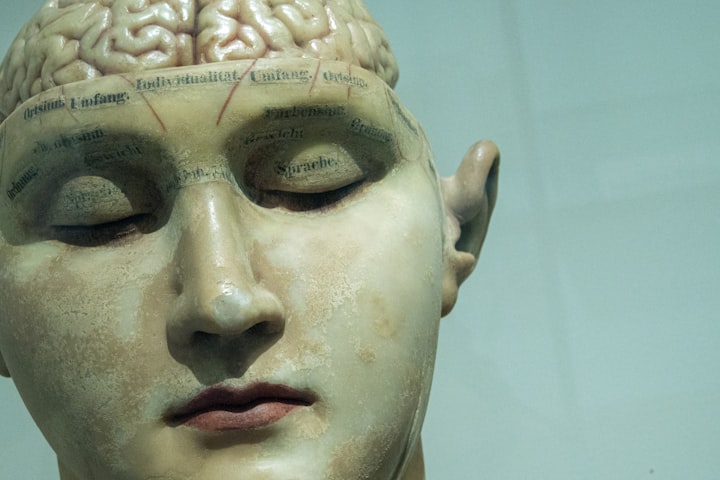

How Is Consciousness Related to the Brain

We tend to regard ourselves, most of us, that is, as the species par excellence. Everything was created by God, so many of us believe, and this greatest being conceivable designed us to be special. It gave each one of us a brain that could think of itself and of myriad other things in extraordinary ways. Apparently, other animals were not awarded with such phenomenal aptitudes. We were the chosen ones, capable of practically infinite development that would lead us back to our Creator. But these brains inside our heads had to be more than just a mixture of organic substances. Thought and all that it entails had to originate from somewhere immaterial, a place where our consciousness could be relatively tranquil, away from the strains of existence. We therefore determined quite intuitively that our brains were separate from our minds. Dualism in terms of body and mind was widely adopted until the timely advent of brains like Hobbes, Darwin, Crick, and Dennett, just to name a few.

Reasons for Doubting that the Mind Is Nonphysical

According to Moore and Bruder (1995), there are seven reasons for doubting that the mind is nonphysical. The characterization problem stipulates that it is difficult to differentiate between an immaterial mind and nothingness given that the mind is regarded as non-divisible, non-spatial, non-tangible, and other such negative characterizations. The individuation problem points out that a physical mind cannot contain more than one consciousness, but that the same goes for a non-physical one, which is quite inexplicable. The emergence problem argues about the undeterminable moment in human history when an immaterial mind might have appeared, and against the necessity for such a mind in terms of evolutionary survival. The dependency problem stresses the conditional existence of mental states upon the existence of brain ones. The no-necessity problem emphasizes the fact that “brain scientists never find it necessary to postulate the existence of the mind to explain and account for what happens in the brain” (Moore and Bruder 239). The interaction problem underlines the inherent difficulty in envisioning a link between mind and brain. And the understanding problem articulates the fact that an immaterial mind would imply a lack of comprehension between a collective of minds.

The above seven reasons may have paved the way for a number of inventive theories postulated by a few contemporary thinkers. Penrose, according to Horgan (1989), proposes that a thought may involve, at first at least, a number of quantum states each performing some sort of calculation. When these states, due to fluctuations in mass and energy, collapse into a single one, they trigger changes in the neural structure of the brain. “This physical event correlates with a mental one…The important thing to remember, Penrose says, is that this quantum process cannot be replicated by any computer” (Horgan 33). Penrose is acknowledging a somewhat dualistic view, but seems more pressed to assert the impossibility of artificial intelligence. For scientists like Penrose, it is hard to swallow the possibility that a species could create another species, that non-organic material could also ponder about its existence, and that we are, after all, just very sophisticated machines.

Consciousness as Part of the Brain

Freedman (1994) reiterates Penrose’s position in regards to consciousness while reminding us that the brain absorbs information using electrical impulses transmitted between neurons: “Perhaps…these signals start off in a quantum mechanical mishmash of states that allows the simultaneous existence of countless billions of different patterns; out of this quantum mechanical mix, one pattern turns up that fulfills the task at hand — it ‘clicks’ — and that’s the pattern that becomes a conscious thought” (Freedman 94). One major shortcoming in Penrose’s theory, relates Freedman, was that any kind of energy in the brain could not exist in a quantum mechanical mixture of states since all the activity in the brain would interfere with it and instantly cause it to choose a single state. But Hameroff, Freedman recounts, discovered a site where a quantum mechanical pulse would be insulated from the rest of the brain — the microtubule. Hameroff demonstrates that “underlying the transmission of signals between nerve cells is a complex network of microtubules arranged in bundles. Individual microtubules, in turn, are built of tubulin proteins; each has a ‘slot’ in which an electron can slide to and fro. Some anesthetics freeze the electron in place, affecting aspects of consciousness” (Freedman 95). In order to solve a problem, the brain must handle an enormous amount of processing, which is more easily accomplished if it is processed on more than one level. The microtubules might represent the first level, and neurons the second. Of course, Hameroff’s idea did not fall on deaf ears. With its obvious implications, Penrose was able to complete his sketch of consciousness. His quantum mechanical states were now, without any interference from the brain, free to choose, having gained some sort of free will. Freedman has the following thought: “What a great practical joke nature will have played on us if all the thinking that has gone into uncovering the ultimate laws of the universe turns out to reveal that one of the biggest clues was woven all along into the very fabric of thought itself” (Freedman 98).

Margulis, imparts Liversidge (1993), finds many similarities between consciousness and the ways of microbes, pointing out that if consciousness is “a living system’s developing ability to create, remember, recall, and use representations of aspects of itself and its environment, then it’s possible to argue that microorganisms are conscious” (Liversidge 10). Margulis also proposes that the mammalian brain displays signs of its origin as a mass of microbes, forever attempting to do what they did before in their primordial state. Our learning may ultimately stand for their continued growth. Furthermore, it is also appropriate to mention the mitochondria, which inhabit us, giving us energy and getting in turn the nutrients that they need in order to survive.

Following his somewhat illuminating encounter with Penrose, Horgan (1994) takes on Crick, a pure materialist. The significance of a severed corpus callosum is obvious to a fellow like Crick. In a brain injured in such a way, consciousness, not necessarily perception, is impaired. “Clearly, consciousness has no existence independent of what has been called the ‘meat machine’ but is lodged firmly within it” (Horgan 91). Many documented cases illustrate the fact that consciousness is but another illusion perpetrated by wishful thinkers. In one particular case, for example, the patient severely suffered from epilepsy. Severing her corpus callosum was the only known way to eliminate most of her pain. Following the procedure, a number of tests revealed that she possessed two distinct selves, each acting independently from the other. Her brain hemispheres were responding to stimuli as if each one represented her true consciousness. She was, for example, able to positively reply to a question with one side of her brain and then negatively respond with the other.

Lemonick (1995) explores the recent theories about consciousness where Crick seems to hold a prominent place. For Crick, “consciousness is somehow a by-product of the simultaneous, high frequency firing of neurons in different parts of the brain. It’s the meshing of these frequencies that generates consciousness…just as the tones from individual instruments produce the rich, complex and seamless sound of a symphony orchestra” (Lemonick 42). Increased brain activity may hold the key to what we refer to as consciousness. Perhaps, the existence of consciousness is positively correlated with brain activity. Evolution may offer the potential for consciousness to every species, but some sort of Darwinian competition may be the actual trigger that eventually drives a species to this “higher” existence.

Morrison (1992) defends Dennett’s idea that “the stream of consciousness is no single flow, not even a Joycean one, but a turbulent, gappy, much-branching stream whose full texture we cannot sense or recall. Many cognitive experiments, much observation of damaged minds, inform that view” (Morrison 117). Dennett believes that machines will one day be able to think. This new species will not possess the passivity of von Newmann computers, forever serially computing trees of deductions. Instead, they would probably be comparable to parallel computers, using probabilities in order to execute tasks, learning by experience as much as by makeup, being quite unpredictable: all too human.

Is There a Consciousness Centre?

Dennett, says Killheffer (1993), refers to “the imagined consciousness center as the ‘Cartesian Theater’ and considers it ‘the most tenacious bad idea bedeviling our attempts to think about consciousness.’ Neuroscience and psychological research strongly indicate that no such consciousness center exists” (Killheffer 57). The fear of losing the immortality of the soul and our moral bearings are instances of blind belief and forced hope. Our eyes, for example, reminds us Dennett, contain a blind spot where the optic nerve connects to the back of the eye, but of course we are not aware of the gap in our vision. “‘One of the most striking features of consciousness…is its discontinuity’” (Killheffer 58).

Dennett, according to Sedivy (1995), equates the brain with the hardware of a computer, and consciousness with the software. Nevertheless:

The function of many of the brain’s parallel processes is that of “content-fixation.” Multitudes of parallel processes bear “simple” contents from which even more “complex” coalitions bearing more “complex” contents form… Our brains probe themselves for information. These “probings” function to select an “answer,” thus yielding something like a question and answer sequence… If brains have an overarching function, it is to “produce future” by knowing what to think about next… Their function is to anticipate the future so that an organism’s chances of success in its environment are increased by allowing it to behave appropriately in anticipation of rather than simply in response to a course of events… Brains ask themselves questions in order to produce answers. (Sedivy 460)

According to Sedivy, Dennett also believes that we organize in our brains a set of habits of mind in the course of our early childhood development. The structure of this organization takes the form of serial chaining where habits can be either added or replaced. Learned habits are therefore linked to the various events that occur in one’s life. Talking to one’s self can be easily seen as a prime example of this progression of associations.

Dennett (1995) draws from Darwin the basis for many of his theories. “Darwin suggests all design in nature can be explained in terms of mechanisms — what I call cranes — of one Darwinian algorithmic process piled on top of another. To me this is the best, most beautiful idea I’ve ever encountered” (Dennett 121). Moreover, evolution and artificial intelligence represent for Dennett the same story on different time scales. Natural selection postulates that we are the descendants of macromolecular robots, and artificial intelligence claims that we are composed of robots. Finally, for Dennett, people “have given up their toes, legs, immune system, metabolism, and retreated back into the brain — the only place that really matters. The rest can all be mechanism, but please let consciousness be exempt from that” (Dennett 122). The human race is growing up, declares Dennett. Most of us miss the wonders of our lost childhood, but we still grow up. And we have to think like grownups.

Closing Remarks

There is a stronger probability that consciousness is bound to the brain than separate from it. The dualistic view stems mostly from our egocentric attitude about the world, whereas the materialist one arises from our inquiry into the nature of the world. We tend to regard the world with hopefulness and dismay, hoping that a better world awaits us while fearing that it may not. This contradictory attitude alone illustrates our mental downfall. We have grown in many respects but have yet to cut the creationist umbilical cord. Our imagination may take us where no one has gone before and our intellect may make sense of it, but our stubborn clinging to the past pulls us back into the abyss of ignorance. Most of us are still unable to let go of the want, will, and wish for immortality and its derivatives. These must be replaced by wonder that eventually leads to fulfillment. Our so-called consciousness is a product of evolution. Presently, it can be quite successfully argued that it is fuelled by the brain. However, somewhere up the webs of evolution, it might disconnect itself from the material world and exist in a sphere of pure energy. Only then would consciousness be truly separate from the brain. But until that “glorious” moment, we might as well fuel our consciousness with empirically plausible ideas.

References

Dennett, Daniel C., “Interview”, Omni Fall 1995, p. 120-124.

Freedman, David H., “Quantum consciousness”, Discover June 1994, p. 88-98.

Horgan, John, “Can science explain consciousness?”, Scientific American July 1994, p. 88-94.

Horgan, John, “Quantum consciousness: Polymath Roger Penrose takes on the ultimate mystery”, Scientific American November 1989, p. 30-33.

Killheffer, Robert K. J., “The consciousness wars”, Omni October 1993, p. 50-59.

Lemonick, Michael D., “Glimpses of the mind: What is consciousness? Memory? Emotion? Science unravels the best-kept secrets of the human brain”, Time July 31, 1995, p. 34-42.

Liversidge, Anthony, “Bacterial consciousness: Why spirochetes think as we do”, Omni October 1993, p. 10.

Moore, Brooke Noel, and Bruder, Kenneth, Philosophy: The Power of Ideas, Mountain View, California: Mayfield Publishing Company, 1995.

Morrison, Philip, “Narrative Gravity”, Scientific American March 1992, p. 116-117.

Sedivy, Sonia, “Consciousness Explained: Ignoring Ryle and Co.”, Canadian Journal of Philosophy September 1995, p. 455-483.

About the Creator

Patrick M. Ohana

A medical writer who reads and writes fiction and some nonfiction, although the latter may appear at times like the former. Most of my pieces (over 2,200) are or will be available on Shakespeare's Shoes.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.