The Cherry, the Ice Cube, and the Straw

Their Effects on Gender Differences in Water-Level Task Performance

Abstract

Over the past few decades, numerous studies have shown that a great number of adults (mostly women) have trouble with various versions of Piaget’s Water-Level Task. They seem to fail to realize that liquids remain invariantly horizontal despite the orientation of their containers. Theoretical interpretations of this curious fact and of the gender differences have focused around biological, sociocultural, and interactional hypotheses. In the present study, 120 female and 120 male university students were assessed for their performance on the Water-Level Task, which included the addition of three cues (i.e., a cherry, an ice cube, or a straw). It was hypothesized that gender differences will decrease and that performance will increase. While the latter hypothesis was definitely supported, the former hypothesis was not.

Introduction

Gender differences, whether gargantuan or Lilliputian, regularly capture our attention more than gender similarities, probably accounting for the widely shared but mistaken idea that males and females are mostly different. The considerable attention devoted to gender differences on Piaget’s Water-Level Task may be but another instance of this assumed gender inequality. Most studies utilizing variations of this procedure have shown males outperforming females, especially when the task was visual in nature. However, studies that also incorporated more realistic (or haptic) assessment tasks found males and females to perform in similar ways (Berthiaume, Robert, St-Onge, & Pelletier, 1994; Robert, Pelletier, St-Onge, & Berthiaume, 1993). These differences suggest that it may be the visual component of the Water-Level Task that is especially problematic for females. That is, the task requires mental rotation, a spatial ability that whether due to socializing factors or biological mechanisms, males seem to possess in greater measure than females. The hypothesis to be tested in this study is that the simple addition of a few cues (i.e., a cherry, an ice cube, or a straw) may decrease the necessary reliance on mental rotation abilities, thus minimizing or eliminating the gender differences usually observed in this procedure.

Various approaches to this problem have been used in countless studies since Rebelsky (1964) reported that some of her undergraduate and graduate students, especially females, had failed Piaget’s Water-Level Task. In the great majority of subsequent cases, males continued to outperform females. Using a component-skills analysis, Kalichman (1988) reviewed 20 such studies done between 1964 and 1986, all reporting a better performance by males than by females. Available “theories” meant to account for these gender differences in the Water-Level Task were either biological (e.g., X-linked genetic models, maturation rates, and hemispheric lateralization), or experiential (e.g., knowledge of relevant physics, gender roles, task expectancy, and learning history). In a more recent study, Amponsah and Krekling (1994) examined the directional biases in performance on a multiple-choice Water-Level Task using 149 male and 268 female university students. All the participants that erred lacked the understanding of the horizontal levelling property of liquids, and once again, females performed worse than males.

The present study proceeds on the assumption that the common failure of females on the standard Water-Level Task is an artifact of the fact that standard assessment procedures confound an understanding of horizontality with various incidental spatial relation abilities. To test this hypothesis, the present study involved three potential cues: a cherry, an ice cube, or a straw (instead of just water), in a standard version of Piaget’s Water-Level Task. It was anticipated that with the addition of these cues, which were expected to minimize the rate of spatial relation abilities, observed gender differences would decrease and performance of female participants would increase.

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 240 students (120 females and 120 males) from the University of British Columbia, most of them recruited in the largest library, voluntarily participated in this study. Most study majors were covered (accounting to zoology), and age ranged from 17 to 50 years (Mean = 20.9 years, Standard Deviation [SD]= 4.1 years).

Materials

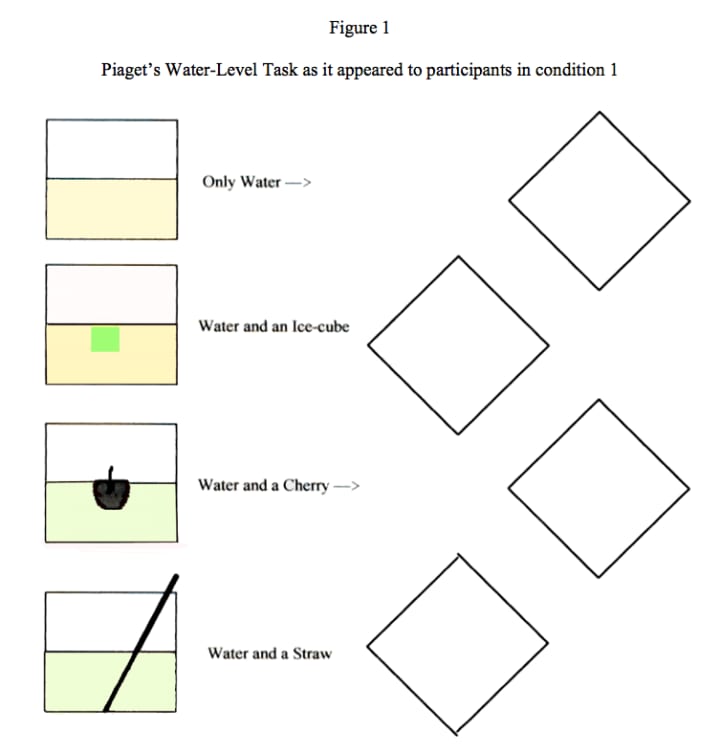

Each participant was given a one-page questionnaire, which consisted of a short introductory note regarding the nature of the study followed by demographic questions concerning gender, age, study major, and occupation. A short paragraph instructed the participants about the actual task. Four drawings, representing half-filled glasses and situated on the left side of the page, served as cues for the four tilted (45°) figures, representing empty glasses and situated on the right side of the page. Participants were simply asked to indicate, by drawing lines across the tilted empty glasses, their best understanding of how the water or water level would appear after the container had been tilted.

The order of the drawings was partially counterbalanced using a 4x4 Latin square design. Performance was scored by measuring the angle between the drawn line and the horizontal. Following established procedure, only angles greater than 5° were counted as significant errors. Participants with more than one error (out of the possible four) were considered as having failed the task.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned one type of questionnaire out of the possible four (differentiated by the order of the drawings). Each type of questionnaire was completed by 60 participants (30 females and 30 males), all of which were unfamiliar with Piaget’s Water-Level Task.

Results

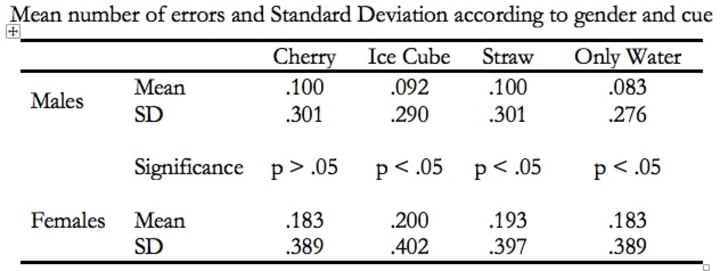

Out of the 120 female and 120 male participants, 96 females (80%) and 109 males (90.8%) passed the Water-Level Task, while 24 females (20%) and 11 males (9.2%) did not. The mean number of errors for females was 0.76, with an SD of 1.51, and the mean number of errors for males was 0.38, with an SD of 1.12 (p < 0.05).

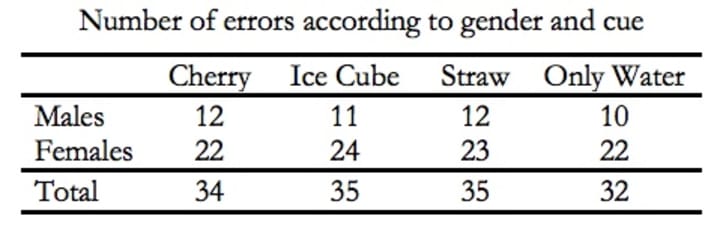

The error frequency for both males and females was approximately the same with each cue (i.e., the cherry, the ice cube, or the straw) including the plain water, but significantly different when gender was a variable.

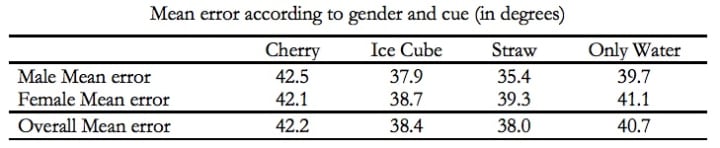

The size of the observed errors ranged from a minimum of 8° to a maximum of 88°, with a mean of 39.8°. There were no significant differences between the errors made on figures that did or did not include an additional cue.

Apparently, the addition of the ice cube or the straw to the water did not decrease gender differences significantly, but that of the cherry showed signs of similitude.

The partial counterbalancing of the figures did not show a statistically significant effect both overall and according to gender. Although not significant, Condition 3, which had the figures ordered as follows: cherry, straw, only water, and ice cube, triggered only 21 errors out of the possible 240 (8.8%), whereas Conditions 1 (only water, ice cube, cherry, and straw), 2 (ice cube, cherry, straw, and only water) and 4 (straw, only water, ice cube, and cherry) triggered an average of 38.3 errors out of the possible 240 (16%).

There was no significant relationship between age and failure on the task, or between study major and failure on the task.

Discussion

In contrast to most previous studies where about 50% of females and 25% of males failed the Water-Level Task, only 20% of female participants and 9.2% of male participants failed the task in this study. Overall performance increased dramatically across trials, whereas gender differences remained proportionally the same.

Although the overall ratio of female/male failure remained statistically the same, the overall rate of failure dropped considerably (about 2½ times lower). It is difficult to attribute this decrease solely to the addition of the cues (i.e., cherry, ice cube, or straw), since all cues were presented at the same time on the same page with the figure of the plain water (without a cue). Visualizing all three cues at the same time with the water by itself may have been a significant influencing factor. Likewise, it is even more improbable to equate this drop with some new and improved understanding of the invariant horizontal state of liquids by a more contemporary population, since other recent studies (Amponsah & Krekling, 1997; Hecht & Proffitt, 1995; Robert & Harel, 1996; Vasta, Belongia, & Ribble, 1994) report the usual rate of failure/success as previous ones. It should be noted that the study by Hecht and Proffitt (1995) could not be replicated by Vasta, Rosenberg, Knott, and Gaze (1997). The samples in the latter experiment, however, were perhaps too small (only 10 participants per condition/group).

The effects of the addition of extra cues on Water-Level Task performance need to be examined further. Cues presented one at a time (one per page), other additional cues, complete counterbalancing, and the elimination of the possibility of experimenter bias through a computer version of the task, are a few of the steps that can be explored in future studies.

References

Amponsah, B., & Krekling, S. (1994). Directional biases in adults’ performance on a multiple-choice water-level task. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 79, 899-903.

Amponsah, B., & Krekling, S. (1997). Sex differences in visual-spatial performance among Ghanaian and Norwegian adults. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 28, 81-92.

Berthiaume, F., Robert, M., St-Onge, R., & Pelletier, J. (1993). Absence of a gender difference in a haptic version of the water-level task. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 31, 57-60.

Hecht, H., & Proffitt, D. R. (1995). The price of expertise: Effects of experience on the water-level task. Psychological Science, 6, 90-95.

Kalichman, S. C. (1988). Individual differences in water-level task performance: A component-skills analysis. Developmental Review, 8, 273-295.

Rebelsky, F. (1964). Adult perception of the horizontal. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 19, 371-374.

Robert, M., & Harel, F. (1996). The gender difference in orienting liquid surfaces and plumb-lines: Its robustness, its correlates, and the associated knowledge of simple physics. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 50, 280-314.

Robert, M., Pelletier, J., St-Onge, R., & Berthiaume, F. (1994). Women’s deficiency in water-level representation: Present in visual condition yet absent in haptic contexts. Acta Psychologica, 87, 19-32.

Vasta, R., Belongia, C., & Ribble, C. (1994). Investigating the orientation effect of the water-level task: Who? When? and Why? Developmental Psychology, 30, 893-904.

Vasta, R., & Liben, L. S. (1996). The water-level task: An intriguing puzzle. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 5, 171-177.

Vasta, R., Rosenberg, D., Knott, J. A., & Gaze, C. E. (1997). Experience and the water-level task revisited: Does experience exact a price? Psychological Science, 8, 336-339.

Author Notes

The author wishes to express his thanks to Professor Don Allen for his haphazard introduction of the Water-Level Task through the testing of the author and a few of his fellow students, and following an article by Hecht and Proffitt (1995).

Warm-hearted gratitude is paid to Dr. Dimitrios Papageorgis for his encouragement and support in getting this project in motion and for his insightful comments on an earlier version of this study.

Immeasurable appreciation and credit is also given to Dr. Michael Chandler for his apropos corrections for improving the paper and for his interest is seeing it reach the stage of publication.

About the Creator

Patrick M. Ohana

A medical writer who reads and writes fiction and some nonfiction, although the latter may appear at times like the former. Most of my pieces (over 2,200) are or will be available on Shakespeare's Shoes.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.