How You Can Achieve a Stable Sense of Self-Worth

And why high self esteem's not all it's cracked up to be

Reminiscent of the push for constant positivity, it’s drummed into us that we should strive for an unequivocally positive self-image. We’re told that high self-esteem is the key to economic and social success with such regularity that I’m beginning to think low self-esteem is itself cause for low self-esteem in the more self-effacing among us.

Personally, I had long suspected that self-confidence was the unseemly remit of self-satisfied narcissists. So much so that when my social psychology professor wrapped up with, “High self-esteem, low self-esteem. What matters more is that it’s stable” some thirteen years ago, I not only awoke from my light doze but felt vindicated at last.

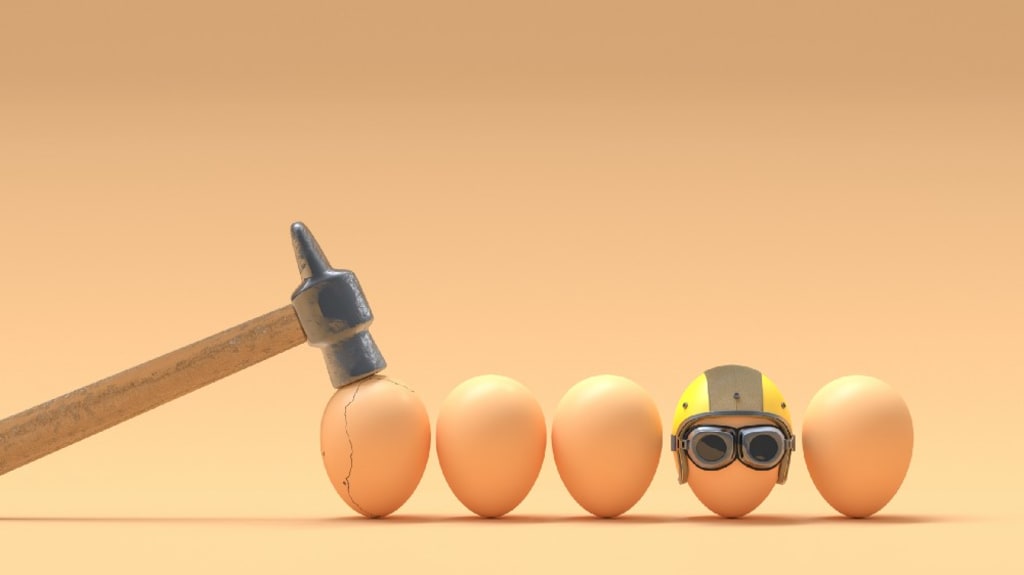

High but fragile self-esteem is a fraught business, stifling self-improvement, and resulting in emotional instability. Fortunately, it can be avoided as long as you aren’t putting all your self-esteem eggs in one basket. But first…

Is high self-esteem all it’s cracked up to be?

High self-esteem is a prized, vaunted quality in the West; you’ve probably been hearing about its merits since your formative years. To this end, perhaps you were even handed a participation trophy — that perennial Millennial cliché — to insulate you from an honest appraisal of your performance, lest your self-esteem were in danger of dipping even slightly after coming last in an egg-and-spoon race.

However, not all cultures place equal weight on self-esteem. In cultures where social cohesion and blending in is prioritised over individualism, high-self esteem is viewed as generally desirable but not essential — a sort of ‘nice to have’. In a study by Brown (2008), Japanese college students, in contrast to their North American counterparts, did not view high self-esteem as a prerequisite for leading a successful life.

The low-down on high self-esteem

Self-esteem is rather more complex than high equals good, low equals bad. For example, low self-esteem does not lead to poor outcome when tempered by mindful self-compassion and the understanding that self-doubt is natural (Marshall et al., 2015). While in terms of high self-esteem, there appears to be a vast chasm between felt and projected; fragile and secure self-esteem.

High self-esteem acts as an emotional buffer against negative social outcomes in daily life such as a stranger taking a dislike to us (Brown, 2010), and even the existential dread that comes from being inconsequential cosmic dust in a vast and pitiless universe (Hornsey, 2018). However, while high self-esteem is protective, this is sometimes to our detriment — but probably not in the way you think.

If you’ve ever worried that your confidence might veer into arrogance, rest assured, narcissism isn’t associated with high self-esteem. On the contrary, narcissists only report high self-esteem whilst grappling with hidden insecurities (Rosenthal, 2005).

This illustrates that there are two faces to high self-esteem, and explicit self-esteem — the confident front one presents to the world (“I’m a fearless thought leader”) — and one’s true feelings and unconscious self-appraisal i.e. implicit self-esteem (God, I’m a fraud) often differ. And where there is a mismatch, there is surely inner turmoil.

High explicit self-esteem paired with low implicit self-esteem is associated with verbal defensiveness in the form of “minimising, justifying, denying responsibility and externalising blame” (Kernis, Lakey, & Heppner, 2008). This is also true among individuals with fragile high self-esteem; anything which threatens self-image —even if it could precipitate personal growth— is derided and dismissed (Paradise & Kernis, 2002).

Other effects of unstable self-esteem include emotional volatility and a sense that one’s self-worth is constantly under attack, so tenuous that it might burst like a soap bubble. Such people are naturally averse to adversity, doing all within their power to protect themselves from the emotional fallout of failure (Paradise & Kernis, 2002).

The perils of all your eggs in one basket

Unstable self-esteem will cause you grief as your self-worth will be at the mercy of factors largely outside of your control (Crocker & Park, 2003). Fortunately, dizzying highs followed by the emotional whiplash of plummeting lows can be avoided.

Parent-child interactions, cultural values, and experiences of acceptance or rejection all shape how we define our self-worth (Crocker & Park, 2003). Most people base their sense of self-worth on domains in which they excel. A child who receives positive feedback from academically-inclined parents after getting good grades will continue to invest in this arena.

Similarly, someone who grew up never feeling safe at home, will have their sense of self-worth inextricably linked to their ability to be self-reliant, an attribute which has historically kept them from harm.

And while it pays to be selective and not base your self-esteem on, for instance, how physically appealing contemporary culture finds you or the model of your iPhone, it’s also beneficial to be inclusive in your approach. As self-worth is contingent, it may as well be contingent on standards you mindfully set for yourself as an adult.

The solution to unstable self-esteem characterised by bouts of feeling worthless, is to consider all aspects of self—you’re not just assistant regional manager, you’re also a birdwatcher, father, and church pianist. (If you are indeed all of those things, that’s simply uncanny and you must write me in the comments.)

In contrast to someone who puts all their eggs in the career ‘basket’, you won’t be crushed by negative feedback from the boss, or a meeting where your idea was shot down. Rather, you will spend the week chuffed at the modest progress you’ve made learning Chopin G minor Ballade №1, and riding high since that weekend walk with Junior where the two of you spotted a Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl.

Speaking of Junior — if you help a child develop a well-rounded identity, losing in an egg-and-spoon race, one flunked exam, or being rejected from a part in the school play won’t unduly threaten their overall confidence and sense of competency, nor will it dissuade them from trying hard in sporting, academic, and artistic pursuits even if their performance is imperfect.

(Even for adults, there’s great value in sucking at a hobby — whether you’re a novice inching your way to mastery, or keenly aware of the fact that you’ll never be more than passably competent. For me, that’s dance classes — a humbling experience each and every time, and a much-needed reminder to not take myself so seriously. Another is yoga. Am I good at it? No. Do I reap all the mind and body benefits anyway? Absolutely!)

Remember, self-worth cannot be derived from any singular aspect of self, nor diminished by any single and inevitable instance of failure. If your high self-esteem is fragile, kept teetering on the edge of a precipice for fear of making a wrong move, it’s holding you back from personal growth and fulfillment.

After all, two primary components of psychological wellbeing — without contradiction — are self-acceptance but also self-improvement for the realisation of your true potential (Paradise & Kernis, 2002).

Parting thoughts

Setbacks and stumbles are part and parcel of any endeavour; any undertaking worth your time will have both highs and lows. If you’ve hitched your entire identity to only one aspect of what makes you you, expect your sense of self-worth to ride the roller-coaster with it.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to refresh stats…

References

Brown, J. D. (2010). High self-esteem buffers negative feedback: Once more with feeling. Cognition and Emotion, 24(8), 1389–1404.

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2003). Seeking self-esteem: Construction, maintenance, and protection of self-worth. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (p. 291–313). The Guilford Press.

Hornsey, M. J., Faulkner, C., Crimston, D., & Moreton, S. (2018). A microscopic dot on a microscopic dot: Self-esteem buffers the negative effects of exposure to the enormity of the universe. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 198–207.

Kernis, M. H., Lakey, C. E., & Heppner, W. L. (2008). Secure versus fragile high self‐esteem as a predictor of verbal defensiveness: Converging findings across three different markers. Journal of personality, 76(3), 477–512.

Marshall, S. L., Parker, P. D., Ciarrochi, J., Sahdra, B., Jackson, C. J., & Heaven, P. C. (2015). Self-compassion protects against the negative effects of low self-esteem: A longitudinal study in a large adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 116–121.

Paradise, A. W., & Kernis, M. H. (2002). Self-esteem and psychological well-being: Implications of fragile self-esteem. Journal of social and clinical psychology, 21(4), 345–361.

Rosenthal, S. A. (2005). The fine line between confidence and arrogance: Investigating the relationship of self-esteem to narcissism. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 66(5-B), 2868.

About the Creator

Angela Volkov

Humour, pop psych, poetry, short stories, and pontificating on everything and anything

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.