Men and women aren’t equal when it comes to concussion

why women are more susceptible to concussion?

Understanding exactly why women are more susceptible to a concussion will be essential if we are to reduce those risks. Recent research has focused on three main theories.

Some researchers have proposed that it may be due to the fact that female necks tend to be slimmer and less muscular than male ones.

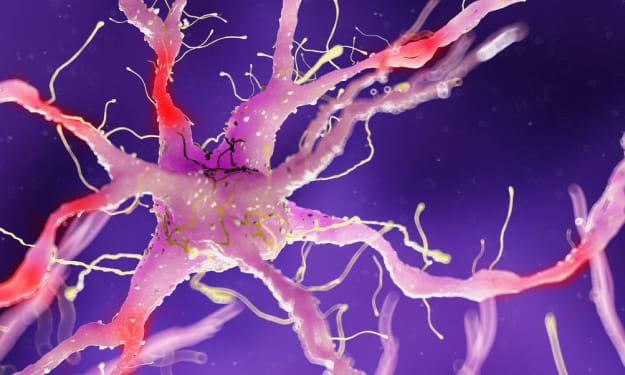

Remember that the brain is free to move within the skull – it is like jelly tightly packed into a Tupperware container – and this means that any sharp movement of the head can cause it to shift around, potentially causing damage.

For this reason, anything that helps to protect the skull from sharp movements should protect you from concussion – and that includes a sturdier neck that is better able to buffer a blow.

“If you have a thicker neck, you have a stronger base, so the likelihood of head movement is much less,” says Raghupathi.

Overall, the girth of a female neck is about 30 per cent smaller than a male, and this increases the potential acceleration of the head by as much as 50 per cent, according to one study.

The second idea that researchers have pointed to is some small anatomical differences within the brain itself. Female brains are thought to have slightly faster metabolisms than male ones, with greater blood flow to the head: essentially, they are slightly hungrier. And if a head injury momentarily disrupts that supply of glucose and oxygen, it could cause greater damage.

The third possibility lies in female sex hormones – with some striking evidence that the risk of concussion changes with varying hormone levels during the menstrual cycle.

Researchers at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, for instance, tracked the progress of 144 concussed women visiting six emergency departments in upstate New York and Pennsylvania.

They found that injuries during the follicular phase (after menstruation and before ovulation) were less likely to lead to symptoms a month later, while an injury during the luteal phase (after ovulation and before menstruation) resulted in significantly worse outcomes.

Exactly why this may be is still unclear, but it could relate to the rise and fall of progesterone levels during the cycle phases.

Previous research has shown that head injuries can temporarily disrupt the production of various hormones, including progesterone. During the luteal phase progesterone levels are highest, and the researchers hypothesise that the sudden “withdrawal” due to head injury throws the brain off balance and contributes to the worse lingering symptoms. In the follicular phase, by contrast, progesterone levels are already have lower and would not drop so dramatically – meaning the resultant symptoms are less severe.

In line with this hypothesis, various studies have found that females taking contraceptive pills are also less likely to suffer severe symptoms following a concussion. Amy Herrold at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, in Chicago, explains that oral contraceptives work by regulating the levels of sex hormones in the body. “So instead of having hormonal surges and dips, over the course of a month, it’s more consistent,” says Herrold, who also works as a research scientist at the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital in Illinois.

Provided that the pill continues to be taken after the concussion, that could prevent the sudden fall in progesterone, which would explain the less severe symptoms.

Complicating matters, the surges in oestrogen and progesterone during the luteal phase might also influence dopamine signalling. Dopamine is implicated in many of the brain’s functions that are influenced by concussion – including motivation, mood, memory and concentration – making it a good contender for a potential mechanism.

Raghupathi’s team’s recent work on animals suggests that the surge of hormones during the luteal phase could render dopamine receptors slightly more vulnerable to perturbation. So, if a head injury occurs during this time, it seems to throw the dopamine signalling off balance in the long term, with potentially important ramifications for those many different brain functions. “It’s the disruption of this connectivity between cells [and] between regions that is a potential basis for the behavioural problems,” Raghupathi says.

But, as Tracey Covassin emphasises, we still don’t know how much truth these hypotheses hold. “I wouldn’t say any of them are clearly determined at this point.”

The different explanations aren’t mutually exclusive: further research may find that the differences in musculature, blood flow, and the balance of hormones and neurotransmitters all contribute.

Future research will also have to investigate other longer-term consequences of concussion. There are concerns, for example, that head impacts can increase the risk of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. We don’t know if women may be at a greater risk here too.

About the Creator

Em Hoccane

Creative writer

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.