Is There a Cure for Type 1 Diabetes? It Appears to Have Worked.

A novel therapy that uses stem cells to create insulin has astonished scientists and given them hope for the 1.5 million Americans who suffer from the condition.

She discovered a request for persons with Type 1 diabetes to participate in a research study by Vertex Pharmaceuticals earlier this year. The corporation was putting a medication to the test that had been created over decades by a scientist who promised to discover a cure after his infant boy and later his teenage daughter were diagnosed with the deadly disease.

On June 29, he received an injection of cells derived from stem cells but identical to the insulin-producing pancreatic cells lacking in his body.

His body now regulates his insulin and blood sugar levels on its own may be the first person to be cured of Type 1 diabetes using a novel medication that has scientists daring to hope that assistance is on the way for many of the 1.5 million Americans who suffer from the illness.

"It's a whole different existence," Mr. Shelton remarked. "It's almost like a miracle." Diabetes specialists were taken aback, but prudence was advised. The study is still ongoing and will take five years to complete, covering 17 persons with severe Type 1 diabetes. It is not meant to be used to treat the more common Type 2 diabetes.

"We've been waiting for anything like this for decades," said Dr. Irl Hirsch, a diabetes expert at the University of Washington who was not involved in the study. He would like to see the results, which have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed publication, repeated in a large number of people. He also wants to know whether there will be any unexpected side effects and whether the cells will last a lifetime or if the therapy will have to be repeated.

"But, in the end," he concluded, "it's an incredible result."

A diabetic specialist at U.C.L.A., who was not involved in the study, concurred with the concerns.

"It's an amazing outcome," Dr. Butler stated. "To be able to treat diabetes by giving them back the cells they are lacking is equivalent to the miracle of insulin being accessible for the first time 100 years ago." And it all started with a 30-year effort by a Harvard University scientist named Doug Melton.

'A Horrendous, Horrendous Disease'

Dr. Melton had never considered diabetes until his 6-month-old son, Sam, started shivering, vomiting, and panting in 1991.

"He was very unwell, and the pediatrician had no idea what was wrong with him," Dr. Melton explained. He and his wife, Gail O'Keefe, took their kid to Boston Children's Hospital. Sam's urine was loaded with sugar, indicating that he had diabetes.

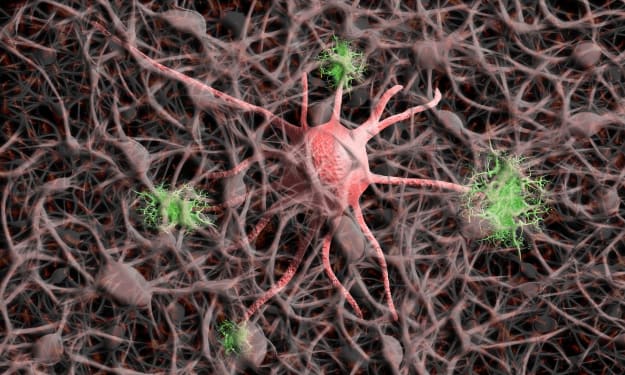

The condition, which arises when the body's immune system kills the pancreas's insulin-secreting islet cells, commonly begins around the age of 13 or 14. Type 1 diabetes, in contrast to the more widespread and milder Type 2 diabetes, is rapidly fatal unless patients receive insulin injections. Nobody ever gets better on their own.

"It's a dreadful, awful sickness," Dr. Butler of the University of California, Los Angeles, said.

Diabetes is the biggest cause of blindness in our country, thus patients are at danger of turning blind. It is also the major cause of renal failure. People with Type 1 diabetes are at risk of having their legs amputated and dying throughout the night because their blood sugar drops during sleep. Diabetes dramatically raises their risk of having a heart attack or stroke. It impairs the immune system; one of Dr. Butler's completely immunized diabetic patients just died from Covid-19.

The expensive expense of insulin, whose price has climbed year after year, adds to the disease's burden.

A pancreas transplant or a transplant of the insulin-producing cell clusters of the pancreas, known as islet cells, from an organ donor's pancreas is the only treatment that has ever succeeded. However, because to a scarcity of organs, such a technique is out of the question for the great majority of people suffering from the condition.

"Even if we lived in a perfect world, there would never be enough pancreases," said a transplant surgeon at the University of Pennsylvania who pioneered islet cell transplants and is now a key investigator in the experiment that treated Mr. Shelton.

The Blue Clues

Caring for young infant with the condition was frightening for Dr. Melton and Ms. O'Keefe. Ms. O'Keefe needed to prick Sam's fingers and feet four times a day to test his blood sugar. She then had to administer insulin to him. Insulin was not even available in the appropriate dose for a baby that young. It had to be diluted because his folks couldn't stand it. If I'm doing this, you have to figure out this awful sickness," Dr. Melton remembered. Emma, Sam's four-year-old daughter, would eventually catch the condition when she was 14 years old. Dr. Melton had been studying the development of frogs but had abandoned that research in order to discover a treatment for diabetes. He turned to embryonic stem cells, which have the ability to transform into any cell in the body. His objective was to convert them into islet cells so that he could cure patients. There was one issue.

The task was to discover out what chemical instructions will convert stem cells into insulin-secreting islet cells. The effort entailed deciphering normal pancreatic development, determining how islets are formed in the pancreas, and undertaking many tests to direct embryonic stem cells to become islets. It was a gradual process.

After years of frustration, a small group of researchers, including Felicia researcher, returned to the lab one night in 2014 to conduct one final experiment.

"We weren't too hopeful," she said. They'd added a pigment to the liquid in which the stem cells were developing. If the cells produced insulin, the liquid would become blue.

Her husband had already called to inquire as to when she would be returning home. She then saw a slight blue hue that grew deeper and darker. She and the others were overjoyed. They have created functional pancreatic islet cells from embryonic stem cells for the first time.

The lab celebrated with a cake and a little party. They then had bright blue wool hats fashioned for themselves, with five circles colored red, yellow, green, blue, and purple to depict the steps the stem cells had to go through before becoming functional islet cells. They'd always hoped for purple but had always ended up with green.

Dr. Melton's next move, understanding he'd need additional resources to develop a medication that might be commercialized, was to establish a corporation

True Testimonies

His was formed in 2014, and his name is a combination of Sam and Emma's. One issue was figuring out how to generate islet cells in huge numbers in a way that others could replicate. It took five years to complete. The business, directed by a cell and gene therapy expert, tested its cells in mice and rats, demonstrating that they worked properly and treated diabetes in animals. The following phase, a clinical study with patients, required a large, well-funded, and experienced organization with hundreds of staff at the time. Everything had to be done to the Food and Drug Administration's stringent standards, which meant preparing hundreds of pages of documentation and planning clinical studies.

Chance stepped in. Dr. Melton ran into a former colleague, David, during a conference at Massachusetts General Hospital in April 2019. David was a professor of genetics and medicine at Harvard and the deputy director of the Broad Institute. Over lunch, who had recently been appointed chief scientific officer at Vertex Pharmaceuticals, inquired of Dr. Melton as to what was new.

Vertex focuses on human illnesses with well-understood biology. "I believe there may be an opportunity,

Meetings were held, and Vertex was bought for $950 million eight weeks later. As a result of the transaction, he was promoted to executive vice president at Vertex.

The business will not reveal the cost of its diabetic therapy until it has been authorized. However, it is likely to be costly. Vertex, like other businesses, has infuriated patients by charging exorbitant rates for treatments that are difficult and expensive to manufacture.

Vertex's task was to ensure that the manufacturing method worked every time and that the cells were safe to inject into patients. Employees operating under strict sterile circumstances watched vessels of fluids providing nutrients and biochemical cues where stem cells were transforming into islet cells. The FDA approved Vertex's first clinical trial, with Mr. Shelton as the first patient, less than two years after it was purchased. Mr. Shelton, like patients who have pancreatic transplants, must take immunosuppressive medicines. He claims they have no negative effects and are significantly less onerous or harmful than continually monitoring his blood sugar and using insulin. He'll have to keep taking them to keep his body from rejecting the injected cells.

However a diabetes expert at the University of North Carolina with no ties to Vertex, expressed concern about the immunosuppression. "We must carefully weigh the difficulties of diabetes vs the possible risks from immunosuppressive drugs." Mr. Shelton's therapy, known as an early phase safety study, required close monitoring and began with half the amount that would be used later in the experiment, according to Dr. James Mr. Shelton's surgeon at Mass General, who is collaborating with Vertex on the trial. Nobody anticipated the cells to work so effectively, he explained. The finding is so remarkable," says the author, "that it's a tremendous leap forward for the discipline.

Vertex was ready to share the findings to Dr. Melton last month. He didn't hold out much hope. "I was prepared to give them a pep talk," he explained. Dr. Melton, who is typically a quiet guy, became agitated during what felt like a critical time. He'd devoted decades and his entire life to this effort. He had a large smile on his face towards the end of the Vertex team's presentation; the numbers were true. He left Vertex to have supper with Sam, Emma, and Ms. O'Keefe at his house. Dr. Melton informed them of the findings as they sat down to dine. "Suffice it to say, there were a lot of embraces and tears."

Mr. Shelton's moment of truth arrived a few days after the operation, when he was discharged from the hospital. He took his blood sugar reading. It was ideal. He and Ms. Shelton ate together. His blood sugar levels remained normal.

When he saw the measurement, Mr. Shelton burst into tears.

"All I have to say is 'thank you.'"

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.