Stumbling into Haiti’s heart-centered world

How a life-long American misfit found the meaning of belonging while working in post-earthquake Haiti.

In February of 2010, a few weeks after the Haiti earthquake, I was on my way to the devastated country by way of the Dominican Republic. I was wearing my new brown cargo pants fit for my latest role as a humanitarian aid worker.

After a three-hour flight from Boston to Miami, I settled into my seat on the next plane to Santo Domingo. I noticed the smiling, chatty Christian missionaries with matching t-shirts and blue jeans interspersed between the many well-dressed, elegant, and perfumed Haitians returning home.

As usual, I felt like a misfit. I was a forty-year-old childless and divorced woman (spiritual but not religious), who rarely wore any t-shirts indicating a belonging to any particular tribe. I was a third-generation Californian in exile, who lived in a tiny condo in Pawtucket, Rhode Island with four cats with whom I had most of my conversations outside of work. They demanded more freedom. I told them I was working on it.

I’d joined the American workforce at the age of fourteen, after my mother arranged for me to learn the art of filing and typing into forms at an insurance broker’s office after school. While my peers played soccer and ran track, I'd learned too well. Instead of following my dreams to write, I'd spent most of my twenties and thirties as a secretary to C-level bosses in some Manhattan high-rise. Becoming a humanitarian aid worker, off to do some social good in the world, was not what I had ever planned. The opportunity came out of nowhere—the way life does.

If only “they” could see me now? I thought as the plane flew across the serene aqua blue water that, for a moment, fooled me into thinking that I was on my way to one of those relaxing tropical vacations at a resort that I only once took with my ex-husband. “They” were the bosses who scolded me for grammatical errors or minor typos; the authoritative, wealthy, and well-dressed ones who thought in exchange for a decent salary and health insurance I’d always be content filing papers into overstuffed cabinets, typing up boring interoffice memos, or wrestling with jammed copy machines.

After arriving in bustling Santo Domingo, a taxi took me to my hotel where a giant room with smooth white polished floors awaited me. It smelled strongly of cleaning chemicals and the air conditioner had made the air so icy cold I shivered. That night I had dinner in the hotel’s restaurant with some high-level colleagues from the UK who’d also flown in to help. The word “colleague” felt like a new pair of shoes I hadn’t quite worn in.

The following day I had lunch with Fritz, the American-born director of the local country office in the DR. He was a kind and nurturing single dad to a daughter he’d adopted in West Africa during another assignment for the organization. As he spoke, I thought of how his obvious genuine concern for others made him a unicorn among bosses.

After lunch, Fritz asked me if I needed anything. I didn’t hold back and told him that I’d forgotten to bring a towel, a necessity I’d likely never be able to find in broken Haiti. He drove us over to a busy department store, where I chose a large pink one, a color I thought would shield my heart from breaking while witnessing so much chaos and destruction.

“Don’t forget to take some Pringles,” Fritz said on our way to the checkout line. “Everyone on the team loves Pringles.”

Something about the thought of humanitarian aid workers munching on mundane junk food while they worked to rescue others jolted me out of the illusion that I was off to team up with a group of superheroes. Everyone who’d posted on my Facebook page had said some version of “You’re so brave,” after I said I was on my way to Haiti.

The next morning, I was on a bus with my pink towel stuffed into my suitcase, feeling more nervous than brave as I gazed out at the rapidly changing landscape from the window. I was thinking about all of the pitfalls and hazards ahead: setting up my tent in the dark when I’d never gone camping before, the cold showers, the lack of electricity, and the threat of aftershocks. What if I cut myself and it gets infected? In my heavy blue backpack, I had my Benadryl, my Neosporin, and my bandaids. Like the girl scout I never was growing up, I was well-prepared for anything.

On the bus, I sat next to one of the senior accountants for our worldwide child-centered humanitarian organization, with whom I’d had dinner the night before at the hotel. He was originally from the Philippines. He told me about swimming in calm blue water with the kind of small sharks that didn’t bite. He showed me some pictures from his phone. When I told him I worked in communications, he thought it had something to do with fixing telephone lines.

After answering a job posting on Craigslist two years before, I’d stumbled into our shared professional world. I was the Executive Assistant to the CEO of the US national office in Rhode Island for the first year. After a meeting where I got scolded afterward for expressing my opinion, I got so upset I almost quit. Instead, with so many cats to feed at home, I pulled myself together and pleaded with my boss to transfer me to the communications department. They desperately needed a writer, and with every fiber of my exhausted being I knew that I could do that job.

When you do what you love, work doesn’t feel like work, I soon learned. After I transferred to my new cubicle and filled my days with writing, editing, and designing, aches and pains I’d felt throughout my body for decades vanished. Almost overnight, I looked ten years younger in the mirror. I was smiling for no reason and finally fitting in with myself.

My new boss in the communications department didn’t like me much however; she never quite welcomed me in, as hard as she tried. Maybe it was because I got thrust upon her team without a choice. Her upper lip quivered uncontrollably every time she stopped by my cubicle to check on a project, as if her nerves couldn’t hide her true feelings. A former news reporter with a thirst for adventure, she could barely hide her envy when I got sent to Haiti. Her tense body language told me that she didn’t think I deserved the opportunity, but unlike me, she had the responsibilities of a husband and children. She didn’t speak French.

The closer we got to Port-au-Prince on the bus, the more I saw how the world had not ended quite like Anderson Cooper and Sanjay Gupta had suggested on CNN. Haitians in suits and dresses were walking everywhere, business-as-usual, buying fruits and vegetables from the markets. Not every structure had collapsed. Life and nature was carrying on. A butterfly flying past on its way through the cloudless blue sky captured my attention.

I thought that maybe, perhaps among the global humanitarians brought together by the unspeakable tragedy, I’d finally find a tribe. I was wrong. With some exceptions, most of the “expert” ex-pats from the mostly European countries weren’t warm or welcoming. Many were dismissive and rude to the naïve American who smiled too much.

Over the following weeks, from many of these ex-pat colleagues, I received sharp verbal lashings, icy glares, and cold shoulders. A French woman beside me in the back of one of the ubiquitous SUVs with our blue logo on the side yelled at a Haitian driver who wasn't fast or efficient enough for her standards. She and others openly called the country a lousy shit-hole where nothing ever got done. The white, male ex-pats in charge blamed these unprofessional outbursts on the fatigue.

My new Haitian colleagues, who’d traumatically lost their homes, friends and family, and way of life, did their best to shrug off the brash and rude ex-pats, but I noticed the furtive, knowing glances between them and the unavoidable eye-rolling. As if the emotional suffering they experienced from the earthquake wasn’t enough, they were now getting steamrolled by the insufferable Westerners who knew nothing about the country’s history and culture and, without question, believed that they knew best.

Maybe because I spoke French decently and asked my Haitian colleagues about their earthquake experiences and took an interest in their lives away from work, most everyone Haitian welcomed me warmly. They had dug loved ones alive out of the rubble with their bare hands, lost grandmothers and aunts praying in churches, and had pulled together in the hours after the earthquake to feed each other. And yet, they were still smiling with dignity, making the best of life under a tent and getting on with work.

I even got invited to a Haitian wedding to take photographs in a giant church that was still standing next to a school that had collapsed into a giant pile of rubble with teachers and children inside. Because I didn't answer my phone during the ceremony, I went back to base camp for another round of harsh reprimands.

The concern and compassion the Haitians offered to each other so naturally, like a big extended family, struck me as profound—and made me wish with all my heart that I was more like them. The team of Haitian drivers who took me everywhere on the bumpy roads of Haiti became my brothers. We cared and looked out for each other and, among them, I never felt alone or out of place.

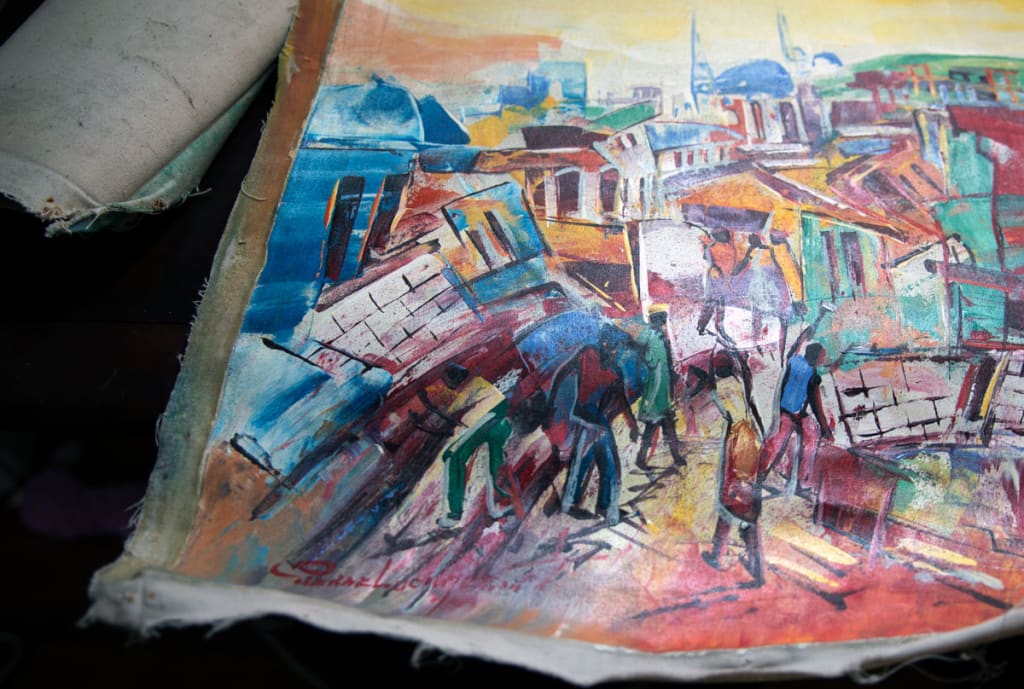

A decade later, after finally making it to the more spacious home I promised my cats, found unexpectedly in the American Southeast, I still have my pink towel with me. I’m still friends on Facebook with Fritz and many of the kind Haitians with whom I worked after the earthquake. I quit the Rhode Island office at the end of 2010 and spent most of the following year in Port-au-Prince as the Communications Manager, a position I earned after proving myself the previous year. I took photographs, wrote blogs, and transmitted emergency situation reports to the global offices, but most of all I learned more about life and how to belong in the world as a heart-centered human.

About the Creator

Heidi Reed

Heidi Reed started writing short stories at the age of fourteen and never stopped, always dreaming of becoming a professional writer one day. She recently self-published her memoir on Amazon called "Sight Unseen: A true story."

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.