The State of Mental Illness in America

Part 3 of 5: The Bureaucracy of Noble Intent

In 1840, activist Dorthea Dix was compelled in her fight to improve the quality of life and living conditions of those with mental illness. After lobbying for more than 40 years, Dix successfully persuaded the U.S. government to fund the building of 32 state psychiatric hospitals. Hence the institutional inpatient care model was born, a laudable change indeed. By the mid-1960s, community-based mental health care became largely a global movement due to the decline in the living conditions in over-crowded and underfunded state hospitals and asylums, also a laudable change.

Let’s take a critical look at the implementation of both care models to determine the possible root causes of long-term failure in the mental health policies and care models. Below are a list of the pros and cons for each care model as well as the criticisms that occurred over time.

Institutional Inpatient Mental Health Care Model.

Pros:

• The patient environment was controlled and safe

• Increased access to professional mental health care

• Families received support and help needed to properly care for their loved ones.

• Local state governance was tasked with funding associated mental healthcare costs.

Cons:

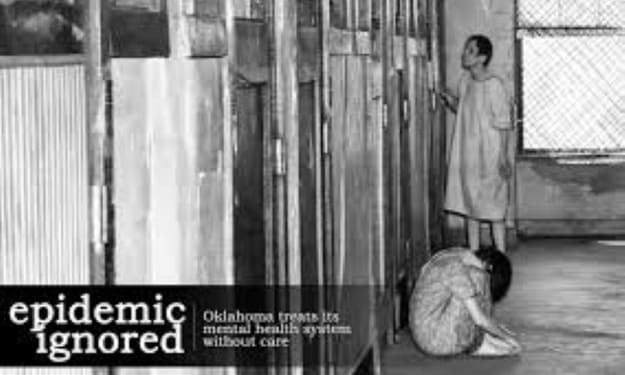

• Facilities became over-crowded

• Not enough staff to properly care for the growing population

• The buildings and physical structure became run-down and difficult to clean and maintain against the backdrop of over-crowding.

• In some instances, patients were injured or abused by staff or fellow patients.

• Lack of necessary resources and tools to provide appropriate care

• Physicians began performing experimental treatments in search of new effective treatments

• Many methods of treatment and management to prevent self-injury and harm did nothing to improve mental wellness and likely worsened the illness such as restraints and isolation.

Criticisms:

• Each state was forced to absorb the costs of building inpatient facilities and all costs associated with maintaining the program such as costs associated with building maintenance, staffing wages and education, professional staff to provide treatment, costs of providing treatments, and all costs associated with personal care of patients.

• Marked growth in patients needing care occurred

• States not only did not increase funding to account for the increased population and care needs, but many states cut funding to the mental healthcare industry to meet budget requirements.

• There were no standardized care guidelines, funding requirements, or government oversight, and the legal rights of patients were not protected.

• Without legal due process requirements, many people were wrongly and falsely committed to inpatient care.

Community-Based Mental Health Care Model.

Pro:

• Patients get to integrate and function within society

• Patients can live independently or in the comfort of family members

• Patients can continue to receive any all treatments needed that may include psychiatric care, oral medications, and counseling

Cons:

• Patients can refuse any all recommended treatment

• Family members do not have the knowledge and tools to care for patients

• Patients can and often choose not to take recommended medication

• Any patient that does not pose eminent risk to himself or others cannot be forced to adhere to recommended evidence-based treatment

• Patients with confusion, paranoia, and delusions often end up in local jails or state prisons

• Even if patients are willing to participate in recommended treatment, most do not have the financial resources to cover the cost of care or prescriptions.

• Without ongoing treatment and management, patients are often unable to maintain a job or provide for their basic needs.

• Many patients often self-medicate with illicit drugs.

• Some patients, without proper management, commit suicide, injure or take the lives of others during a psychotic break.

Criticisms:

• Mental healthcare and medical healthcare are separate and distinct entities.

• Privacy laws in many states prevent mental health providers from transferring mental health information to primary physicians or direct family members without consent.

• No financial provisions or other resources available to receive needed treatment.

• Many patients, without access to needed treatment, end up in the streets and in local jails and state prison systems.

The review of each care model reveals problems with the implementation process. Prior to implementing policy changes that impact population health, it is necessary that policy makers implement a change process plan that considers and prepares for a variety of possible outcomes and actions plans to respond to any given outcome or behavior change. The plan should also identify any agency, organization, or persons responsible for managing the implementation process and assessing the management of outcomes, and fiscal responsibilities.

Once institutionalized in the in-patient care model, patients essentially lost all their human rights, civil liberties, and access to legal representation. However, deinstitutionalization and the closure of state hospitals was codified by the Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963, setting strict standards that stated that only persons who posed eminent danger to themselves or others could be committed to an inpatient mental health facility and afforded the right to legal representation. Additionally, civil rights activist fought to ensure all persons with a mental illness diagnosis were afforded the same patient rights and civil liberties as all citizens.

Patient’s with serious mental illness are also afforded the same patient bill of rights as any other patient, allowing them the authority to dispute any diagnosis they do not agree with and refusing recommended treatment, even if the recommended treatment is evidence-based. Leung (2002) asserts, “in the management of mentally ill patients, there is a tension between protecting the right of individuals and safeguarding public safety. Well publicized homicides committed by patients with mental illness have placed considerable public and political pressure on the government to reform the mental health act in favor of public protection”.

“A vast majority of mental health specialist and an uncertain percentage of former patients argue that forced confinement is at times justified by safety concerns and to ensure proper treatment is administered. Psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey criticizes reforms gained by civil rights activist stating the reforms have made involuntary civil commitment and treatment too difficult and thus has increased the numbers of mentally ill people who are homeless, warehoused in jails, and doomed by self-destructive behavior to a tortured life” (Amidov, 2018).

Both, civil rights activist and supporters of coercive treatments have compelling arguments that cannot be ignored. There are interlinked issues of safety, science-based medicine, civil liberties, and justice that must be considered. Amidov (2018) expresses the following concerns:

• There is no reliable methodology behind the decision of whom to commit.

• Confinement does not offer effective treatment.

• Involuntary psychiatric hospitalization is often a damaging experience.

• Involuntary confinement undermines the patient-doctor relationship.

• Coercive treatment of people with mental illness is discriminatory.

I agree with Trestman (2018) who states, “these arguments are moot when meaningful effective treatment is neither available nor accessible”.

Regardless of what side of the coin a person supports, the one obvious truth is that our mental health system is broken and in need of repair. It is time for experts on both sides come together to find a solution rather than simply making arguments that results in no change.

I will leave you with the following words from Herschel Hardin,

Herschel Hardin is an author and consultant. He was a member of the board of directors of the Civil Liberties Association from 1965 to 1974 and has been involved in the defense of liberty and free speech through his work with Amnesty International. One of his children has schizophrenia.

The public is growing increasingly confused by how we treat the mentally ill. More and more, the mentally ill are showing up in the streets, badly in need of help. Incidents of illness-driven violence are being reported regularly, incidents which common sense tells us could easily be avoided. And this is just the visible tip of the greater tragedy – of many more sufferers deteriorating in the shadows and often, committing suicide.

People asked in perplexed astonishment: ” Why don’t we provide the treatment, when the need is so obvious?” Yet every such cry of anguish is met with the rejoinder that unrequested intervention is an infringement of civil liberties. This stops everything.

Civil Liberties, after all, are a fundamental part of our democratic society. The rhetoric and lobbying results in legislative obstacles to timely and adequate treatment, and the psychiatric community is cowed by the anti-treatment climate produced. Here is the Kafkaesque irony: Far from respecting civil liberties, legal obstacles to treatment limit or destroy the liberty of the person. The best example concerns schizophrenia.

The most chronic and disabling of the major mental illnesses, schizophrenia involves a chemical imbalance in the brain, alleviated in most cases by medication. Symptoms can include confusion; inability to concentrate, to think abstractly, or to plan; thought disorder to the point of raving babble; delusions and hallucinations; and variations such as paranoia. Untreated, the disease is ravaging. Its victims cannot work or care for themselves. They may think they are other people – usually historical or cultural characters such as Jesus Christ or John Lennon – or otherwise lose their sense of identity. They find it hard or impossible to live with others, and they may become hostile and threatening. They can end up living in the most degraded, shocking circumstances, voiding in their own clothes, living in rooms overrun by rodents – or in the streets. They often deteriorate physically, losing weight and suffering corresponding malnutrition, rotting teeth and skin sores. They become particularly vulnerable to injury and abuse. Tormented by voices, or in the grip of paranoia, they may commit suicide or violence upon others. Becoming suddenly threatening or bearing a weapon because of delusional perceived need for self-protection, the innocent schizophrenic may be shot down by police. Depression from the illness, without adequate stability — often as the result of premature release — is also a factor in suicides. Such victims are prisoners of their illness. Their personalities are subsumed by their distorted thoughts. They cannot think for themselves and cannot exercise any meaningful liberty. The remedy is treatment — most essentially, medication. In most cases, this means involuntary treatment because people in the throes of their illness have little or no insight into their own condition. If you think you are Jesus Christ or an avenging angel, you are not likely to agree that you need to go to the hospital.

Anti-treatment advocates insist that involuntary committal should be limited to cases of imminent physical danger — instances where a person is going to do bodily harm to himself or to somebody else. But the establishment of such “dangerousness” usually comes too late — a psychotic break or loss of control, leading to violence, happens suddenly. And all the while, the victim suffers the ravages of the illness itself, the degradation of life, the tragic loss of individual potential. The anti-treatment advocates say: “If that’s how people want to live (babbling on a street corner, in rags), or if they wish to take their own lives, they should be allowed to exercise their free will. To interfere — with involuntary committal — is to deny them their civil liberties.” Whether or not anti-treatment advocates actually voice such opinions, they seem content to sacrifice a few lives here and there to uphold an abstract doctrine. Their intent, if noble, has a chilly, Stalinist justification — the odd tragedy along the way is warranted to ensure the greater good. The notion that this doctrine is misapplied escapes them. They merely deny the nature of the illness. Health (Official) Elizabeth Cull appears to have fallen into the trap of this juxtaposition. She has talked about balancing the need for treatment and civil liberties, as if they were opposites. It is with such a misconceptualization that anti-treatment lobbyists promote legislation loaded with administrative and judicial obstacles to involuntary committal.

The result, …will be a certain number of illness-caused suicides every year, just as surely as if those people were lined up annually in front of a firing squad. Add to that the broader ravages of the illness, and keep in mind the manic depressives who also have a high suicide rate. A doubly ironic downstream effect: the inappropriate use of criminal prosecution against the mentally ill, and the attendant cruelty of committal to jails and prisons rather than hospitals. Corrections officials once estimated that almost one third of adult offenders and close to half of the young offenders in the correction system have a diagnosable mental disorder.

Clinical evidence has now indicated that allowing schizophrenia to progress to a psychotic break lowers the possible level of future recovery, and subsequent psychotic breaks lower that level further – in other words, the cost of withholding treatment is permanent damage. Meanwhile, bureaucratic roadblocks, such as time-consuming judicial hearings, are passed off under the cloak of “due process” – as if the illness were a crime with which one is being charged and hospitalization for treatment is punishment. Such cumbersome restraints ignore the existing adequate safeguards – the requirement for two independent assessments and a review panel to check against over-long stays. How can such degradation and death — so much inhumanity — be justified in the name of civil liberties? It cannot. The opposition to involuntary committal and treatment betrays profound misunderstanding of the principle of civil liberties. Medication can free victims from their illness — free them from the Bastille of their psychosis — and restore their dignity, their free will and the meaningful exercise of their liberties.

Read more at: https://mentalillnesspolicy.org/media/bestmedia/uncivilliberties.html

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.