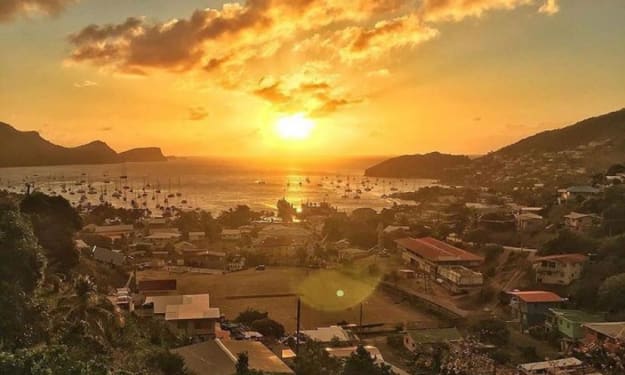

In 1997, my sister, my mom, and I left our home island of St. Vincent and the Grenadines to be reunited with my dad after fourteen years. We left the island with broad smiles, hearts full of hope, and suitcases filled with dreams.

My suitcase held my three most important goals: an education, a career, and wealth. Education was of the ut-most importance because I had lived all my life with a mother who couldn't read or write. Despite that, she pushed and beat us in the direction of education. I re-membered being asked to read passages from one of my textbooks as she had the belt ready-in-hand in case I seemed to be fumbling. But how would she know if I had made a mistake? She couldn't help me if I needed it. I hat-ed getting whipped, so I made sure my sister and I learned how to read, with the help of our teachers.

Mother was a stay-at-home mom, but not by choice. No one would hire her with her level of education. She took what was considered the worst and most degrading job in our culture—a sanitation worker. No one wanted that job. Mom cleaned the streets of our communities in St. Vincent and waited for payday at the end of the month when she brought home practically nothing. She thought I didn't see the disappointment and despair in her eyes, a look that said, "I have failed my children again."

I had experienced poverty at its worst, and I hated it. So, I knew I needed to work as hard as I could to reverse the cycle of poverty. In the 1980s, Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey were popular. They were young, beautiful, and talented. I wanted that career. I decided I was going to be a pop star. I fantasized about being on stage with bright lights and people screaming my name and making a lot of money. I had watched Oprah Winfrey on TV my entire life, and I wanted the financial independence she had. Mom used to say, "That's what I want for you girls—to be women of power." I knew she felt trapped in a poverty-stricken community, and so did I. So, I packed wealth in my suitcase of dreams.

According to shows I'd watched on television, Ameri-ca was the land of opportunity, a place where all of your dreams come true, a place where it was possible to “be all you can be”—to borrow the slogan the U.S. Army began using in 1986. There were clean streets and bright lights. When my dad came home from America to visit, he often told stories of things I was all too eager to experience. Buying grocery on the island was expensive, so when he told the stories of buying sugar and rice and flour at only 65 cents a bag, I was flabbergasted. He went on and on about buying gold for little or nothing and being able to purchase two pairs of sneakers for less than one hundred dollars. To me, this was riches, because in St. Vincent this is unheard of.

I have always told myself I would master every as-pect of my life, so I can become a well-rounded individu-al, and I would not have to depend on anyone. I wanted to be a vocalist, a model, a banker, and a speaker because I envied people like Oprah who spoke fluently without fear. I wanted to be that courageous, so when I opened my mouth, people would listen.

When I told my mother about all my fantasies of owning many different businesses, travelling the world, and being able to go to the bank and make a withdrawal without flinching, she would turn to me and say, “To be able to do that, you will have to work hard, child. Only an education can get you all these things you see.” With a sly smile as she turned her back to me, she would whisper, “Jack of all trades, master of none.”

I saw how, despite all her hard work, Mom still brought home nothing sometimes, and I knew I didn’t want that. There were hardly any jobs on the island, and I witnessed many students completing their high school ed-ucation with top O-levels subjects, still with no jobs and nothing productive to do. They graduated from high school and advanced to the “Academy of Idle Hall.” I al-ways desired independence. Staying at home and being dependent on my mother was not anyone’s idea of inde-pendence.

When the day came to leave St. Vincent, three of us made the trip: my mother, my sister Lala, and me. I was sixteen years old at the time, and Lala was fourteen. We left behind my eight-year-old sister, Terry, to stay with a great aunt. How could we explain to our little sister that this separation was only temporary as we walked away from her to move to another country? It was one of those tough decisions my mother was forced to make. As a mother, you are a nurturer, an educator, a builder, a con-stant, dependable force in your children’s lives. Any sense of security our mother had provided was shattered for Terry.

On March 20, 1997, my sister, mother, and I packed all our belongings for the trip to the airport. Mom gave everything we couldn’t take with us to family members and close friends. It was a painful farewell because that place was the only home I had ever known.

When we left for the airport, it seemed like the entire village went with us. We were accompanied by a bus full of people. The ride felt like the longest one-hour ride I had ever had, and we cried almost the entire time. As we ap-proached the airport, my heart began to beat faster. I knew it would be a very long time before I saw any of these people again, and I was scared.

We were a bit early for the flight, so the twenty people who came to see us off gave speeches about obedience and how we should go to school and get an education, so our parents can be proud of us, and that we should always remain respectful to our mom and dad—but in all the well-wishing, they forgot Terry. She stood far away from us on her own, looking lost.

When it was time to check-in, we reached a door that said, “only passengers beyond this point.” Terry grabbed hold of Mom and screamed loudly in agony. It was deaf-ening. Mom cried too, but it was too late to turn back.

My sister and I held onto Terry and Mommy, and we cried as if it were a funeral. It took two adults to pry Terry from my mother’s arms. As we walked onto the airstrip to board the plane, we looked back to give one last wave be-fore we disappeared. I saw my little sister’s face pressed against a fence, still screaming for her mother. It was a face that hunted me for years.

It was cold when we landed in New York, so cold I could almost feel my intestines freezing up. Instantly, my lips dried and began to crack. My dad and his youngest brother Edward met us at the airport, bringing with them three huge jackets. When I put on my jacket, I couldn't find my hands in the sleeves. Nevertheless, I was excited, because I had finally arrived at the rich place. All my life, I had seen this place on television, and now I could see what the buzz was about. I had dreamt about this America most of my life. I believed life was easier here, so I was eager to open my suitcase of dreams. My expectation was that wealth could appear overnight and opportunities would present themselves with the snap of a finger.

As we walked to the parking lot, the number of cars I saw stunned me. I had never seen so many cars in one place at one time. I looked at Lala, mesmerized. We got to my dad’s white Chevy van and left JFK Airport.

I knew this was the change of a lifetime. Words could not express the joy I felt to be where I was at that moment. Yet I felt guilty because we had left one sister behind. I thought it was wrong to be excited when my little sister was in pain, but I just couldn’t contain my excitement.

The entire ride home, I stared out the window, taking in as much of the scenery as I could. I saw streets over-lapping each other, and I was in complete bewilderment because I couldn’t wrap my head around the possibility of concrete doing this. Streets were above us and below us. We were driving in this wide-open space, with hundreds of cars going in one direction at the same time.

The open space was exhilarating. Back in St. Vincent, there were no highways. Most roads accommodated only one lane of traffic in each direction. Now I found myself surrounded by so many streetlights that I had a hard time identifying the night from the day. I looked up to the sky and saw no stars. I was disappointed. I had always loved looking at the stars; it gave me a chance to appreciate God’s creation.

Finally, we arrived at our new home. Although every street had a different name, all the houses looked the same. Our new residence was the basement of one of dad’s older brother Vernon’s house. The basement apart-ment had two bedrooms and a band room. My uncle Vernon had a band that rehearsed there every night.

My excitement at finally being in America soon turned to shock and disappointment when I realized that only one of the two bedrooms belonged to my family, as the other was occupied by cousin Philip the lead keyboard player in the band. The room could barely hold one per-son, let alone four, plus luggage. I couldn't believe it. This is crazy, I thought immediately. Is this what I left my three-bedroom house on the island for? We had to come to this wonderful city where we were supposed to live like kings and queens, but instead we were heaped into one small room in a basement.

I was confused; I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. I dared not open my mouth to say something; my mother would not have it. “Children should know their place,” she would say. I was so disappointed. Someone had lied to us. This was not the place I had seen on TV. Suddenly, America didn’t look so promising. I’d been told the standard of living was better than my native land, but this reality was far worse. I had expected this place to be a palace, and it was anything but. My dad claimed he was unable to find an apartment in time for our scheduled arri-val. He and Mom stayed in the small room in this base-ment while Lala and I went to live temporarily with our paternal grandmother.

No one was happy with these living arrangements. My paternal grandmother hated my mother for reasons I did not understand, and Lala and I had never lived apart from our mother. So, this arrangement made mother un-easy, because she projected her fears of our grandmother onto us. She didn’t want this old woman to mistreat us the way she had mistreated her in the past. Nevertheless, we were grateful we had a roof over our heads. Mom often preached, “Tek liko and live long.” Or she would say, “If yo tek time kill ants yo go fin e guts.” She told us to be patient; things would work out.

Living in the basement really tested my mother’s pa-tience to the limit. There were no boundaries there, just a free-for-all. People came, went, and did as they pleased. Back home, Mom was a neat freak. Her home was her pal-ace, and she cleaned that palace every day. She mopped, swept, dusted, and wiped every inch of the house. Back home, she made one thing clear: everyone was expected to take their shoes off at the door. But here, no one took their shoes off. The door to the front of the basement was nev-er locked, so everyone that came to practice in the band room would just walk in. It irritated her, but she held it in because she was the new kid on the block, and she didn’t want to disrupt anyone’s routine. Under her breath, she would mumble, “God, help us find a place.” During this period, I grew to admire Mom’s patience, as she never complained even when things were so far from what she considered normal. Unfortunately, I did not inherit that trait.

Things changed rapidly for Lala and me, and we found ourselves having to grow up quickly. We had to become familiar with new terminologies, dress codes, and living arrangements. Finding our way around proved to be the biggest challenge because everywhere looked the same. We would go up one street, then another, and I would ask, “Didn't we just come from this direction?” I felt as if I would never get used to this awkward feeling of being new. It was so obvious we had just gotten off the “boat.” This adjustment was emotionally hard because we couldn’t wake up to the sounds of our mother singing a gospel hymn while she sweeps the yard or to her voice yelling, “Only lazy people sleep late, it’s time to rise and shine.” Instead, we woke up to this old woman mumbling and sucking her teeth in frustration, which made us un-comfortable, because we knew she was uneasy with us staying in her home. We could never tell when she was happy because her facial expression always looked mean.

I don’t think there’s a word in the dictionary to accu-rately describe the character of our grandmother. All she needed was a broom, a hat, and a tail. Her sole purpose in life was to make other people’s lives miserable. She stuck her nose where it didn’t belong 99 percent of the time. The remaining one percent, she spent at the doctor. Living with this woman felt like a death sentence. She hated my mom and, by association, Lala and me. It was as if the other grandchildren mattered more. My dad’s family was of East Indian descent, and he was expected to marry an In-dian woman. My mother was black, uneducated, and from a poor family—all characteristics not suitable for a wife.

Uncle Edward was already living at our grandmoth-er’s when we joined the household. He went to work eve-ry day leaving the three of us alone. We were living with a stranger. My sister and I were afraid to make a sound. Once we were up in the morning, we would walk softly to the bathroom, so we wouldn’t disturb her. Mom had given us strict instructions: “Make sure you get up early, brush your teeth, take a shower, do the dishes, sweep the floor, and mop if you have to.” After we cleaned, our grand-mother would act like Inspector Gadget, scrutinizing all our hard work. If it wasn’t pleasing to her, she took her time and did it all over.

The living room in our grandmother’s apartment was very small, yet she managed to fit a large floor model TV, two large sound boxes belonging to uncle Edward, an oversized fish tank, and a coral living room couch set that was covered in plastic. In the sweltering summer months, sitting on the condom furniture was as agonizing as the first time I had sex. The skin-to-plastic friction was brutal. It was painful getting up from the couch. As my skin and the plastic broke the suction, the sweat that ran off the back of my thighs could fill a bucket. It was impossible to sit on the couch without making a sound. When we made any noise, our grandmother would start yelling, “You guys sit down one place. Stop moving up so much.” We were supposed to be robots. She expected us to sit in one spot and not even scratch our noses because that too was a hindrance to her. We were walking on eggshells—something we weren’t accustomed to.

Since the old woman was a diabetic, the food she cooked had no salt or sugar, and we did not find it appe-tizing. She often called my dad and say, “Come get yo children, because they refused to eat what I cook, so you can come buy them fast food.” She dragged her words when she spoke. Mom knew we were picky eaters, so she kept reiterating, “Just eat what she gives you.”

The old woman had arthritis in her joints, and when she would return from the market with lots of bags, she refused to ring the doorbell to make us aware she needed help to get up the three flights of stairs. I often asked her why she didn’t have one of us go with her, to which she always responded, “I’m alright,” as she struggled through the door with the heavy bags.

Everything annoyed her, and she constantly violated our privacy. We discovered that she would go through the letters we received from friends and other relatives from back home. Living with her was like living in prison.

By September 1997, two things happened. We en-rolled in school and we moved into our new apartment on East 21st Street. We enrolled in Erasmus Hall High School. We enrolled in September because in March when we arrived, it was too late in the school year to enroll. The apartment we found had two bedrooms, a huge living room, kitchen, and bathroom, and that made us happy be-cause we were all under one roof. All the floors were cov-ered in red carpet, except for the kitchen and bathroom. Mom and Dad took the room in the front of the apartment, and they gave us the one in the back. I guess they were scared we would sneak out at night. We weren’t walking on eggshells anymore. When we moved in, all we had was a bed—the bed Dad had owned for the longest time. With-in a month, Mom had saved enough money to buy us a bed, so they got theirs back. My mom was always con-cerned about our comfort. I don’t know how Mom did it, but she was always able to make ends meet.

Attending school in Brooklyn was so much different than in St. Vincent. On the island, we had fun despite the strict environment. Whether in school or not, respect was a requirement, and we were expected to show it. Schools on the island believed in corporal punishment, which was administered for a variety of reasons: when a student was being disrespectful, if homework was not done, for not passing an exam, or for arriving to school too late. Stu-dents were suspended from school for profanity or for not adhering to school uniform policy. Girls wore white blouses with brown skirts, while boys wore white shirts and brown pants. Girls were required to wear black bras under their blouses; any other color warranted being sent home. Latecomers were asked to collect garbage around the school or face suspension. Some opted for the latter. The bell rang promptly at eight o’clock every morning, and students had to meet in their homeroom class for prayer. It was routine, and the class prefect headed the devotions. Only the prefect was allowed to keep his or her eyes open during prayer as if God could see us all through the prefect’s eyes. Anyone caught peeking was asked to leave the class until prayer finished.

Things in Brooklyn were very different. I hated the learning environment. Here, I experienced the worst teach-er-student relationships. Students were not reprimanded when they cursed in the presence of teachers and adults. Sometimes, I sat in class and wondered to myself what on earth was going on. It never bothered the teachers. Life went on as if everyone was the same age and on the same level. There was no way to distinguish the adult from the children, except when we sat in class to learn.

Very often, I walked the halls of my new school and saw students standing around doing absolutely nothing but wasting time. The majority of them hated sitting in a class for forty-five minutes to be educated. For some, it was forty-five minutes of pure torture. I took the road very few traveled and was determined to take full advantage of this learning opportunity. I became president of the Future Business Leaders of America (FBLA), as well as president of the National Honors Society. I was especially proud of this accomplishment because to be a part of this society, you had to be an honor roll student and have at least one hundred hours of community service. In addition, I tu-tored elementary school students in English and math after school, was the captain of my school’s varsity volleyball team, and competed against a dozen schools. I was grate-ful for these experiences because they were the main rea-son I came to the United States: to be exposed to all the opportunities this great nation has to offer. I was working on the many dreams I had packed in my suitcase.

Throughout life, we meet many people along the way, some of whom left an indelible mark on us. Dr. Selina Ahoklui was one such person. I met Dr. Ahoklui my first year of high school. She was a history teacher and the co-ordinator of the summer youth program. Although short in stature, this Ghanaian woman towered over her students when it came to a measure of her courage and her strength. She was the kind of teacher who taught self-love, self-value, and how to push for success. She was one of the most influential teachers during my high school years. She understood what it was like to be a black woman in a white world. This woman showed me the true meaning of hard work, independence, and individuality.

Dr. Ahoklui often called upon me when she needed to find something, and I could never locate what she wanted. It was usually something as simple as a garbage bag, a piece of paper, or a book, but I quickly became frustrated and gave up. She would yell in her African accent, “How come you can never find anything? Keep looking!” The lesson I learned was that if you stay diligent and persist at anything, success is inevitable. Years down the line, this lesson would prove significant.

So many things were changing simultaneously. New country, new home, new school, a change in weather and now mom had something shocking to add to our ever-changing life. I remember mom saying she wasn’t feeling in the best of health and needed to make a doctor’s ap-pointment. Later that day, I arrived home from school to find my dad’s youngest sister Gabby, her husband Jorge, and their two children sitting in the living room with mom. My sister Lala was already home from school. As soon as I entered the doorway, I spotted some pregnancy pam-phlets and a pregnancy book.

I asked the daring question, “Whose are these?”

My sister gladly responded, “They belong to Mom.”

I looked at her and said, “Yeah right,” with a grin on my face. I thought that this must have been a joke. She was too old to have a baby. I turned to my mom and asked, “Is it true?”

“Yes,” she replied.

I laughed. “You got my attention. See, I’m laughing; it’s a really good joke.”

There was complete silence.

“Does it look like I’m joking?” Mom responded em-phatically.

That was when it hit me that they were not joking. Everyone saw the expression on my face change in an in-stant. It felt as though someone had just robbed me of my prized possession, my inheritance. It was me against the world. I turned with my backpack on my back and stormed off to my room. I was pissed. Nothing could have gotten me to come off the high I was on. I was high on anger. That moment felt like the single worst moment of my life. I was in shock, in total disbelief.

When I got to my room, I slammed the door shut. I locked it behind me and started blasting my music. Mom wanted me to be happy for her, and I just couldn't be in that moment. I was seventeen years old, and her being pregnant meant harder times for us.

She knocked on my door and yelled, “Open the door.”

At first, I couldn't hear her, since the music was so loud. By the time I heard her, she had been banging for about five minutes. I opened the door, trying hard to fight back tears.

“What do you want me to do?” she said angrily. “Have an abortion? I didn’t have an abortion with you. Why would you want me to do it with him?” She stood in my door way yelling at my me to the top of her lungs about my selfish behavior as I wipe the tears from my eyes. “Do not lock any doors in my house” she yell an-grily, as she points her right index finger at me in a scold-ing manner. She tucked her skirt between her legs and walked away in a rage. As she walked back to the living room, I can still hear her yelling about my selfishness. I slowly closed my bedroom door not locking it out of fear of her wrath. With the door closed I couldn’t hear what was being said about me. That evening I fell asleep bur-dened with worry about my future and this new addition.

Mom had raised us in church, but after coming to the US, we had difficulty finding a suitable church to attend. Still, Mom always maintained a strong faith in God, in everything she did. Her pregnancy taught me a lesson. With this pregnancy, God prepared me for trials to come. Was it a coincidence that six months after coming to America, my mom had gotten pregnant? The answer would come sooner rather than later. Mom still did her best to shield us from the challenges of adulthood. As I got ready to enter my junior year of high school, I had a premonition that things were going to get worse.

It was April of 1998, one month before Mom gave birth to my brother, and I was still feeling sorry for my-self. I worried about how my dad was going to care for five people on his salary. Going to college was a big dream of mine, and I wondered what would happen if he didn’t have the money to send me to college. It was still all about me.

When my parents got married, a honeymoon was the last thing on their minds. They had no money, and even if they had a little extra to go somewhere, my dad was a cheapskate. He was the kind of man who would wear the same pair of pants for twenty years and insist they could go for another ten. He wore shoes until the bottoms fell apart, and still he refused to throw them away. He would say he had to get his money’s worth. You would never find him in name brand clothes or shoes; they were too expensive. In stores, even if he didn’t buy the item, he would still complain about how much it cost. “Why would you buy one shoe for a hundred dollars when you can buy three for that same price?” he would say. “You can get more for your money.” He was the king of cheap. The thing is, I am just as cheap—if not worse.

It was their sixth wedding anniversary. I waited until they left the house, ran to the store, and bought my dad his first pair of Nike sneakers and my mom a pearl neck-lace set. With my paycheck, that was all I could afford. I placed the gifts neatly on the dresser in their room so they would be surprised. But when they came home and went to their rooms, I heard nothing. “What do you think?” I asked. I felt as if I was begging them to be excited about the gifts I had just spent my entire paycheck from tutoring buying. All I got was, “They look good.” I wasn’t really surprised, after all. They had trouble showing emotion, and it was a crime for them to show gratitude for anything.

My mom developed gestational diabetes and needed to be hospitalized before the baby was born. The baby was two weeks overdue, and a C-section was scheduled. He was born weighing in at seven pounds, eight ounces, but because he had water in his lungs, he and Mom spent an extra week in the hospital.

I know I wasn’t so thrilled about a new addition, but I was anxious about the baby coming home. I stood in the window of our apartment and waited for my dad's white Chevy to pull up. I paced back and forth, wondering if they were coming. The moment finally arrived, and they were home. The baby was very chubby, his face was fat, and he was handsome. Mom named him Malcolm after Dad because naturally, there needed to be a Junior in the family.

Somehow, all looked right with the world. I was doing well in school, participating in many different activities. Things looked good for this suitcase of dreams I kept car-rying around. I was sure that by eighteen I would graduate high school, then go on to college, graduate, and get mar-ried by twenty-five. I would also land my dream job and start a family. But God had other plans for me. At that moment, God was setting up our family for something we could never have imagined. This thing was going to rock our foundation, the very essence of our existence. This thing was going to make us dig deep to find our strength to live.

That year, mom had promised to go to school to get the education she never had as a child. I couldn't imagine what it was like to live in her shoes. She was unable to spell her own name. She depended on others to give her directions. It was difficult being in this country and unable to read. She would have died of starvation. On the week-ends, I would write simple words like to, do, that, the, and it to help her identify words, but teaching an adult to read is more difficult than teaching a child. I became frustrated quickly with her because I felt as though she wasn't put-ting in enough effort. During the week, I would ask her to spend some time studying the words while I was in school, but she preferred watching her stories on TV. Af-ter some time, it appeared she no longer had any interest in learning how to read, so I didn't push her. Instead, I contacted the adult literacy school and enrolled her, and she was scheduled to start in spring of 1999. However, after the birth of my brother, she was unable to attend be-cause we couldn’t afford a babysitter for my brother. We reached out to the school and they rescheduled her classes for the month of August. I admired my dad greatly be-cause even though things were difficult, I never once heard him complain. He loved taking care of his family. He loved the idea of all of us under one roof, where we could all sit and eat dinner at the same time, talking and laughing. Mom was the disciplinarian, while Dad was just laidback.

With no job prospect in sight, someone recommended Mom for a babysitting position. The parent of this new-born came to our house, interviewed my mom, liked what she saw and heard, and offered Mom seventy dollars a week. Mom accepted. The kid’s name was Andrew. Dad would get up at seven in the morning, pick up Andrew, and drive his mom to the train station. In the evenings, when it was time for Andrew to leave, Dad would drop him and his mother home if he was around. All of this came at no extra charge. He didn’t have to do it, but that was just his nature. He was a helper. The level of kindness I saw in this man I called my dad was unbelievable. Dad worked the graveyard shift, and by the time he arrived home, it was already 4:00 a.m. To get up early to get An-drew was commendable. Andrew and Malcolm were the same age. In total, Andrew spent 13 months under Mom’s care.

Things were looking up for us. We had our own apartment, enough food, and Mom was happier than I had ever seen her before. She wasn’t as overly protective as she’d always been, and she didn’t seem to get upset as easily as before. If we were ever late with the rent, Dad would tell the landlord that he’d given one of the kids the rent money to bring to him, and she had forgotten. The landlord knew my Dad had an honest heart, so he would always tell him, “I’m not worried about the rent. I know I will get it.”

Nineteen ninety-eight was one of our best years.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.