As medicine attempts to narrow its diversity gaps, one profession stands out as a stubborn anomaly.

Medicine

Erica Taylor appears to be destined for a career in orthopedic surgery. Her father, Hall of Fame receiver Charley Taylor, was a 13-year member of the Washington Redskins' football team, and she holds degrees from the University of Virginia's top biomedical engineering department and Duke University Medical School, one of the nation's best medical schools. She'd wanted to be an orthopedic surgeon since she was 15, after spending every other Sunday watching physicians on the sidelines of football games.

Taylor requested a meeting with a local orthopedic physician as a sophomore to learn more about the subject. He agreed wholeheartedly. When she came, though, his mood shifted. "He responded, 'Oh, you're Erica,' and proceeded to tell me for 20 minutes that orthopedics was too difficult and that most people like me went into family medicine or maybe OB-GYN," Taylor, who is Black, claimed. "I recall crying my eyes out as I walked to the elevator." It was my first realization that various rules applied to different individuals."

Taylor had been surrounded by individuals who wanted her to succeed since she was a child. "In ortho, it wasn't always the case," she told STAT. "I had to decide whether I was going to let this stop me or use it as fuel." She went with the gasoline option. She is not only Duke Health's first Black female orthopedic surgeon, but she is also the chief of surgery at Duke Raleigh Hospital.

Taylor, like any Black, Hispanic, or Native American orthopedic physician, is a rarity. While medicine as a whole, and even elite specialities such as dermatology, thoracic surgery, and otolaryngology, have begun to raise the percentage of persons of color in their ranks, orthopedics has scarcely moved. Black people make up less than 2% of individuals working in the field, Hispanics make up 2.2 percent, and Native Americans make up 0.4 percent. Even Asian American doctors, who are overrepresented in medicine, are underrepresented in orthopedics, accounting for only 6.7 percent of these experts.

In part, this is due to the fact that there are few candidates of color in medical school to begin with: Black, Hispanic, and Native American students are underrepresented in medical school. However, according to a STAT research, the small pool of potential orthopedic surgeons from underserved neighborhoods is whittled down at practically every stage: Aspiring orthopedists from these groups are less likely to apply to the specialty, to be accepted into residency programs, and, if accepted, to complete their education. Not only is the pipeline tiny, but it's also full with leaks.

STAT talked with hundreds of orthopedic surgeons, ranging from presidents of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and department chairmen to residents and medical students hoping to work in the profession one day. Their reactions reflected befuddlement, rage, and irritation. Some see signs of progress, while others are concerned that orthopedics will never become much more diverse.

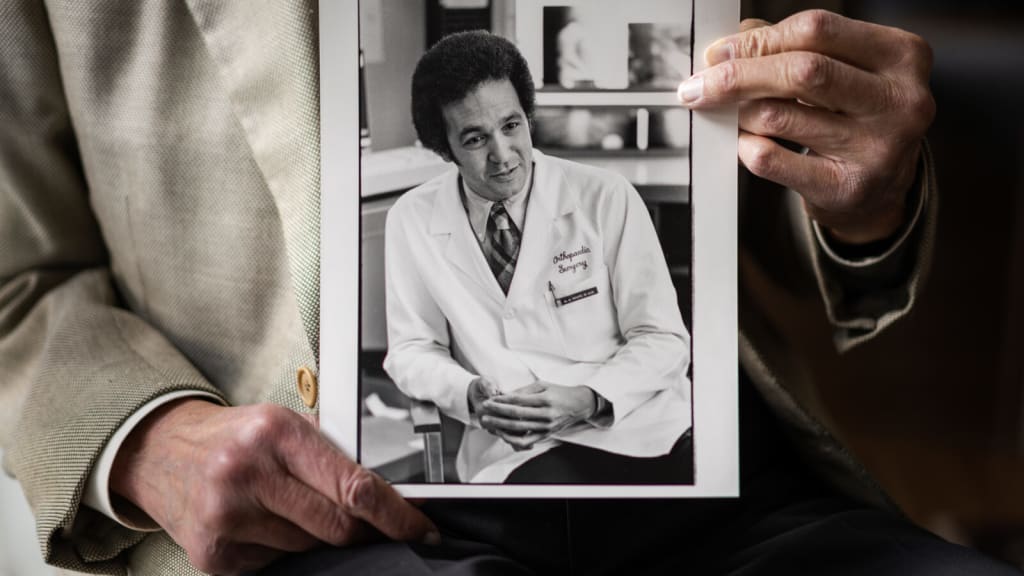

The problem isn't that the field's leaders aren't aware of it. Orthopedic surgery, which deals with sports injuries as well as musculoskeletal damage, degeneration, and malignancies, was one of the first medical professions to openly identify its diversity difficulties decades ago. Augustus White III, a pioneering physician who was Stanford's first Black medical student, Yale's first Black orthopedic resident and professor of medicine, and Harvard's first Black teaching hospital department chief, prompted the AAOS to form task forces, hold discussions, and award those in its ranks who pushed diversity efforts since the 1980s.

However, despite all of the hype and accolades, the needle has scarcely moved. In some ways, the situation is worse now, despite the present national focus on diversity. The racial and cultural diversity of orthopedic residency programs has historically been the lowest of any specialty, and the number of orthopedics residents from underrepresented groups in medicine decreased between 2002 and 2016, despite their percentages among medical students rising. From 40 in 2002 to 60 in 2016, the number of orthopedics residency programs in the United States without a single trainee from one of these groups rose.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.