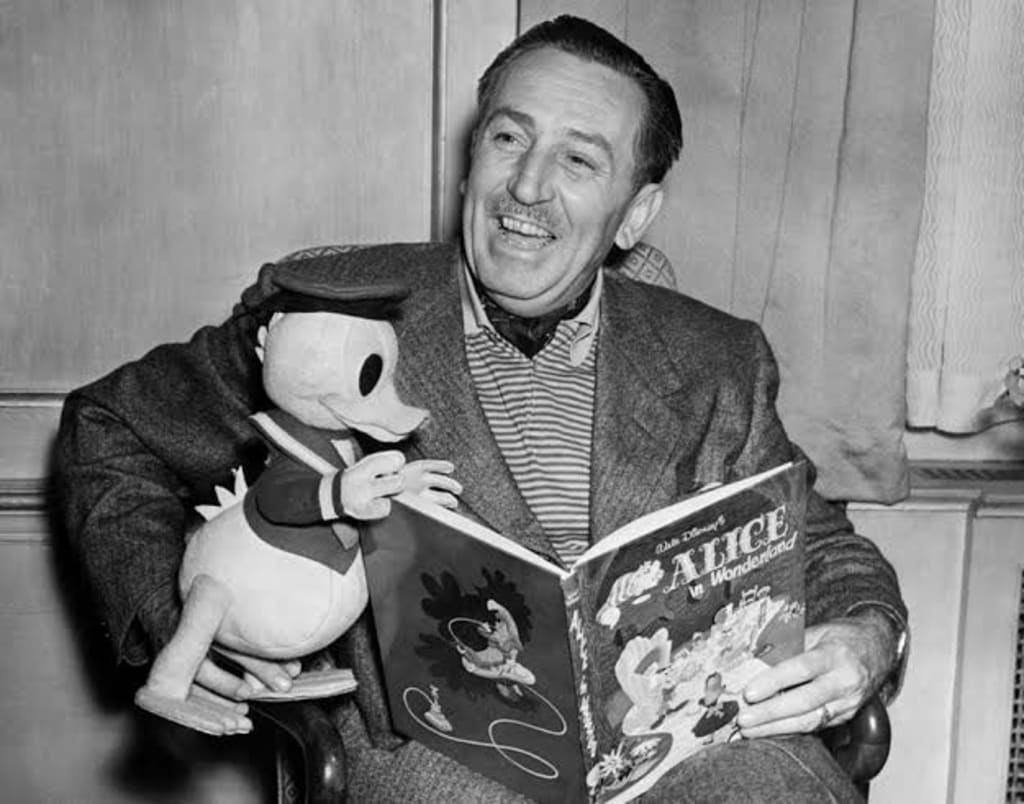

The Ugly Truth About Walt Disney

How could the creator of the "Happiest Place on Earth" have such a conflicted and questionable past? Check out the ugly truth about Walt Disney to discover a darker side to the Mickey Mouse creator!

The year is 1928 and 27-year-old Walter Elias Disney is sitting on a train after a pretty crumby business meeting. He takes out his faithful pencil and starts sketching, drawing something that he has no idea for decades to come will change people’s perception of a certain kind of vermin. Above the sketch, he writes, “Mortimer Mouse.” He then takes it home and shows his wife Lily. She chuckles and tells him, “Come on Walt, you need a cuter name than Mortimer…What about Mickey?” Walt smiles and agrees, Mickey will work. This is such a cute scene from the annals of American history, but did we add that Mr Disney drew that sketch at a time when he may have had some very bad thoughts in his head?

Did you know about the time he turned up at a Nazi meeting and later gave a tour of his studios to one of Adolf Hitler’s favourite people? Today we’ll talk about the good, the bad, and the ugly, but before we change into our devil’s advocate uniform, let’s first paint a picture of Walt that makes him look as wonderful as some of the beloved cartoon characters he created. He came into this world on December 5, 1901, to his Irish-American pop, Elias, and his German-American mom, Flora. He was then the youngest brother to Herbert, Raymond, and Roy, and he also had an older sister, Ruth. It was when he was living on a farm in Marceline, Missouri, and still only four years old, that his parents saw that little Walt had a talent for drawing. First, he drew a horse that belonged to a neighbour, and later his parents watched on fondly as Walt started copying the cartoons of newspaper cartoonist Ryan Walker. Walt had some skills, there was no doubt about it. But life wasn’t easy by any means. By the time he was in junior high school, he was getting up at 4.30 am to deliver newspapers, something that didn’t exactly meld with success at school.

With bad grades, he nevertheless didn’t lose sight of his sketching career, later taking a course in cartooning at the Kansas City Art Institute. His other love at the time was Motion Pictures, those black-and-white films where dreams came true. When the war was raging in 1917, Walt was one patriotic son of a gun, and though much of his time was spent attending night courses at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, he had ambitions to go over to the battlefields of Europe and fight for the US army. He was too young, but after forging a birth certificate he got a job as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross. Still, by the time he got to France, the war was over. His war effort, in the end, amounted to drawing sketches on the sides of an ambulance, not knowing right then that when that appeared in Stars and Stripes magazines, he was already on his way to going up in the world. So, his future as a cartoonist was already almost in the bag. What’s interesting, given his close relationships with some American pro-Nazis years later, was his gung-ho attitude to fighting those bad guys of Europe. His relationship, though, was what we might call ‘complicated.’ But let’s concentrate on the budding cartoonist for now.

At the age of just 18, he was laid off from a job at Pesman-Rubin Commercial Art Studio with another aspiring cartoonist. That was Ubbe Ert Iwerks. This was a partnership made in heaven. If Disney was the visionary of the pair, Iwerks, himself the son of German immigrants, was a brilliant and fastidious artist. It was he who brought Disney’s imagination into the world. He would barely sleep for days on end, sketching and sketching, so that minutes-long cartons were ready in a matter of a few weeks. This was laborious work for one man back then. Walt Disney was now getting into animation rather than static-drawn cartoons, which led to him being contracted to make what were called “Newman's Laugh-O-grams.” He then incorporated this studio using cash he still had from a month-long project called Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists business, and he got to work on cartoons such as Jack the Giant Killer.

These early cartoons were about as simple as you could get, for us anyway, but back then they were pretty decent fare. Disney kept going, and at 21, he and his brother Roy, who’d just gotten over a bout of tuberculosis, went into business by creating the Disney Brothers Studio. This became the Walt Disney Company in time, a company that now brings in around 67 billion dollars a year and has a net value of $203.61 billion. With his new company, Disney got Iwerks back on board and together they worked in Hollywood. It was there at age 24 that he married Lilly, an inker, and soon they had a daughter and adopted another daughter. In 1927, he created a character that would become the blueprint for many others. That was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. This guy was super popular, and unlike those older cartoons, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit moved around like a human. This was a new age of animation. But after quite a bit of success, the character was taken over by others and so Disney had to come up with another character. He still liked the idea of Oswald, so he drew something not too different. As you know, that was Mortimer, who changed a fair bit over time from his original appearance.

Many years later, Disney would write: “I only hope that we never lose sight of one thing – that it was all started by a mouse.” By the way, that high-pitched voice that makes Mickey sound like he had just been kicked in the balls was Walt Disney’s voice, although he had to give it up over time because all those cigarettes he voraciously chugged on harmed his vocal cords. Anyway, Mickey turned to life in 1928 with the cartoon Steamboat Willie. He was an immediate sensation. With Iwerks as the head animator and a good team of other animators, that mouse was making children and adults jump for joy. And they were more impressed when Disney started putting sound to Mickey Mouse cartoons. Sound films or so-called “talkies” back then were state-of-the-art. Mickey needed a love interest, and throughout the 1930s, his new darling Minnie came to life. In 1931, Mickey’s pet, the bloodhound Pluto, also came to life. But the triad wasn’t enough, and in 1934 an eternally happy duck came on the scene in the cartoon “The Wise Little Hen.” Disney, still in his early 30s, was a star. Now his studio employed over 200 people. The Golden Age of Animation was beginning, and Disney, always the visionary, started thinking about feature-length animations.

He did that in 1937 with his “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” This would become just one of his films that later got him into trouble with some folks. For instance, this film would make the actor Peter Dinklage irate, or at least another iteration of it. We’ll come back to this. Grossing 6.5 million (about 127 million in today’s money) Snow White became the highest-grossing movie at the time. Disney almost immediately then started working on Pinocchio and Fantasia, and the rest is history. His fame was cemented. Life was good. But on the other side of the world a man named Adolf Hitler was talking about the “Jewish Problem”, and a lot of poor, angry Germans were listening to him. War was on its way, and Mr Disney somehow found himself partly wrapped up in it. Let’s now change into our devil’s advocate clothes. So, the war broke out and Disney did his bit for the Allied war effort. That was making an anti-Nazi propaganda cartoon called “Der Fuehrer's Face”, originally titled “A Nightmare in Nutziland.” In it, Donald Duck is a Nazi, but, spoiler alert, it was all just a bad dream. As the war came to an end. Mr Disney was becoming a lot more conservative. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, lots of things in life need conserving, but he was also, how shall we say, a rampant anti-communist. Given the extreme violence that Joseph Stalin had wreaked on mankind, that wasn’t a bad thing either, but did Disney’s views have a selfish bent? The so-called “Red Scare” got ugly in America, and many people who were just progressives who wanted a fairer society were hunted down. One of the men doing the hunting, and one who seemed to lack ethics at times, was the FBI’s, J. Edgar Hoover.

He promoted this Red Scare propaganda and the attendant restrictions of free speech, which is never a good thing. The Red Scare also promoted moving against those associated with the American labour movement, which suited the big employer, Mr Disney. Hoover was called by some a “racist, a bigot, and a homophobe”, inside a country that had an awful track record for racism. Hoover tried his best to bring down the Civil Rights movement and with it the great Martin Luther King Jr. He was also pretty close to Disney, who himself once testified against some former labour unionists at the House Un-American Activities Committee. He’d branded these three guys, one of whom worked as an animator for Disney, as communists. Suffice it to say that during those paranoid times that could be sufficient to destroy a person’s life. For his help, in 1954, Hoover made Disney a "full Special Agent in Charge Contact.” While this doesn’t make Disney some kind of celebrity despot, it gives you a good idea of what was going on in his mind. Some of those isolationists in the US weren’t just against war and communism, some of them talked about what they called “The Jewish Problem”, that thing Hitler had talked about. One of them was the business magnate Henry Ford, who was better known for making cars than he was for his “virulent racism and antisemitism.” Ford and Disney were very good friends, and you might ask if they shared some similar beliefs. Listen on, before you make your mind up. Was Disney as anti-Semitic as Ford? That’s the million-dollar question.

Disney donated money to some Jewish charities and his friends have stated that he didn’t come across as anti-Semitic, but like we just have, some people have questioned the folks he liked to hang around with. The first person ever to get access to the Disney archives concluded after lengthy research that Disney “was not anti-Semitic, nevertheless, he willingly allied himself with people who were anti-Semitic.” He also said Disney “willingly, even enthusiastically, embraced anti-Semites and cast his fate with them.” Nonetheless, a Jewish composer who worked with Disney later said calling him antisemitic was “absolutely preposterous.” We told you it’s complicated. For instance, in the original “Three Little Pigs” cartoon, the big bad wolf tries to disguise himself as a Jewish character. The wolf in disguise speaks Yiddish, and his appearance by one writer was described as having a “grotesquely phallic nose, a long black beard and an ankle-length caftan.” It was this kind of appalling behaviour that the Nazis embraced, and Walt Disney was the one who produced the cartoon. Sure, when it was re-released in 1948, Disney had that character taken out, but some critics now say he only did that because he was told there’d be criticism from Jewish communities, as well as shock, given that six million Jews had just been murdered by Hitler. We can’t forget, though, that the original character looked like he was straight out of Nazi propaganda. We also have to look at other matters of perhaps greater importance, which do make Disney look like a bit of a Nazi sympathizer.

He attended pro-Nazi meetings at the German American Bund, aka, the American Nazi Party. Art Babbitt, who worked with Disney as an animator said this: “I observed Walt Disney and Gunther Lessing, Disney’s lawyer, there, along with a lot of prominent Nazi-afflicted Hollywood personalities. Disney was going to these meetings all the time.” Not a one-off then. He didn’t just get lost and end up in a room full of guys and say, “Oh, the Nazi meeting, wrong place.” This was an American Nazi organization and its racist, anti-semitic Nazi ideology was clear to everyone. There was always a lot of this sentiment going around at these meetings, so Disney must have heard it. But did he agree with it? Then there was that time he gave a German woman named Leni Riefenstahl a tour around his studios. The year was 1938, and this woman, a film director, was already a close acquaintance of Adolf Hitler. Hitler adored her because she made propaganda movies for him, three in total. This is how she described first watching Hitler at one of his many speeches: “It seemed as if the Earth's surface were spreading out in front of me, like a hemisphere that suddenly splits apart in the middle, spewing out an enormous jet of water, so powerful that it touched the sky and shook the earth.” To her credit, her films didn’t expressly show anti-Semitism, they just embraced what she thought was the greatness of Nazism. She was an excellent artist, but after the war, she wasn’t exactly popular, even though she admitted that she hadn’t been aware of Hitler’s genocidal intentions.

She later said that meeting him, “was the biggest catastrophe of my life.” But that doesn’t mean she didn’t agree with Nazi racist and anti-semitic ideology when Disney was giving her the royal treatment at his studios. She too believed the Jews were the cause of all the world’s problems, remarking after that visit that it was “gratifying to learn how thoroughly proper Americans distance themselves from the smear campaigns of the Jews.” That also doesn’t mean Disney thought the same, but again, he sure liked to flirt with Nazism. His kind treatment of this woman may have just been about the art of filmmaking, or as people have since pointed out, it might have been in some part an effort to get his films back into Germany after Hitler banned Hollywood because he said it was “controlled by the Jews.” Moving on from Nazism, was Disney racist when it came to African Americans? Were his movies just ”harmless fun” or inherently offensive when it came to people with darker skin colour?

Back in Disney’s day, many black activists said yes, his films are racist. They said he perpetuated those ugly and racist black stereotypes in his cartoons. It was the film “Song of the South” that got him in the most trouble and still does today. The present Disney company is a bit ashamed about this movie, and there is good reason to feel that way. Here is how one person summed up the synopsis of the film, “A plantation full of happy-go-lucky slaves who are more than willing to do the bidding of their masters.” Another critic called it “One of Hollywood's most resiliently offensive racist texts.” And yet another called it “a dangerously glorified picture of slavery.” One thing for sure is Disney was not doing realism here. As one person later said, it certainly was an “insult to American minorities”, but did it mean Walt Disney was a racist? Was he just ignorant when he should have been sensitive to moral standards and people’s feelings? That same person who had access to the Disney archives didn’t think he was racist.

He once said, “Walt Disney was no racist. He never, either publicly or privately, made disparaging remarks about blacks or asserted white superiority. Like most white Americans of his generation, however, he was racially insensitive.” That much is true, but you also have to remember that Disney fought for a black actor to win an Honorary Academy Award. He might have been insensitive, but according to a man named Floyd Norman, who back then was the first black animator for Disney, his boss was no racist. Norman said, “Not once did I observe a hint of the racist behaviour Walt Disney was often accused of after his death. His treatment of people—and by this, I mean all people—can only be called exemplary.” With that movie, was Disney just trying to ignore some of the terrible things that had happened on those plantations? Sticking your head to the ground is never a good thing when it comes to atrocities, but that doesn’t always mean he agreed with the atrocities.

As you’ll soon see, Disney was a bit of a utopian, but he still shouldn’t have idealized the horrors of slavery. Disney still has a lot of detractors today. Meryl Streep for instance said recently that Disney “had some racist proclivities” and “supported an anti-Semitic industry lobbying group and was a gender bigot.” Hmm, gender bigot, ok, can we add that to the list of Disney’s apparent attributes? His friend and animator once said about Disney, “He didn’t trust women or cats” and Disney himself said in a 1938 letter to a female job applicant, “Women do not do creative work”. He added that the work was for men and girls should bear in mind that only jobs such as Inker or Painter are open to them. So yes, he certainly had a sexist side, just as many people did back then. Just before he died in 1966, he was working on a project called the “Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow”, a plan for a real, functioning town.

This was Disney’s idea of utopia, a community where no one lived in poverty, where there were no slums or joblessness. It was the ideal place, kinda something like Hitler dreamed of in his utopia. And Disney’s little world also had to be autocratic, meaning one strong leader had total power. But it didn’t sound too bad when Disney described it, once saying, “It will be a community of tomorrow that will never be completed, but will always be introducing and testing and demonstrating new materials and systems. And EPCOT will always be a showcase to the world for the ingenuity and imagination of American free enterprise.” So again, you have to connect a lot of dots to make Disney the bad man some people say he was. It’s only too easy these days to call someone far-right or far-left when something they have said has been taken out of context and exploited on social media. You have to dig deep and keep an open mind when you read articles calling people far-something. It’s generally never that simple, and when it is, it’s obvious.

Nothing about Disney’s faults was that obvious except for his hate of labour unions. These days the Disney company does give warnings about some of its old movies such as Dumbo and Peter Pan and The Jungle Book, writing that they have “negative depictions... of people or cultures.” And let’s not forget about what Peter Dinklage said about the remake of Snow White. He called it a “backward story” about short people living in caves, which might be as offensive to him as a movie about black people living in trees would be to someone of African descent. We don’t think Dinklage wants the Snow White story to be brushed under the carpet of human history or for Walt Disney to be cancelled into perpetuity, but he probably wants people to learn from the relics of past ignorance and insensitivity.

So to conclude things, with Walt Disney, the evidence isn’t strong enough to say without any doubt that he was a racist or antisemitic, but there’s enough to not completely let him off the hook. One thing for sure is he had some pretty dodgy friends.

About the Creator

Jayveer Vala

I write.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.