Move Over Michelle and Barack...Here's America's First Black 'Power Couple'

And, Like The Obamas, They Are Also From Chicago.

When we study slavery, we do not usually consider northern slavery. After all, slavery was only a southern phenomenon, right?

Wrong.

In the beginning, and for at least one hundred years before the thirteen colonies declared themselves independent of England, slavery was present in each and every one of those original thirteen colonies.

Right up until 1787, slavery was perfectly legal and vigorously practiced in each of the Northwest Territories as well, which, in time, would become the states of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin after passage of the Northwest Ordinance.

Within this vast expanse, and pursuant to the Ordinance, at least three but no more than five states could be and were established. Although the framers of the Constitution could not bring themselves to end slavery throughout the entirety of their fledgling nation-state, they did outlaw the continuation of slavery in the territories which, again over time, became the aforementioned states. This meant that within the freshly minted Northwest Territories, which were still in the process of being “confiscated,” to put it mildly, from the resident inhabitants, slavery was “grandfathered” in as a nod to those wealthy white people who owned slaves at the time of passage of the Ordinance in 1787.

Slavery in Illinois

The enslavement of black people in Illinois has a long and complex history. Slavery was first brought to the Midwest by French explorers, namely, LaSalle, Joliet, and Marquette from the mid- to late 1700s.

Interestingly, each of these “explorers” tried and failed to set up shop at the confluence of the tiny river now known as the Chicago River where it entered what was then known as the Great Illinois Lake (Lake Michigan). But the resident Indigenous peoples turned them back every time, refusing the Frenchmen’s offers of trinkets, trade goods, weapons…and Christianity.

Instead, the Native Americans did allow a free black Haitian (Jean Baptiste Point DuSable), who had come up from New Orleans, to settle there in what the Pottawatomie, Illinois, Miami, and Huron peoples all called “Eschickagou,” or “land of stinking onions” because of the miles and miles of endless undulating “fragrant” fields of wild onions and leeks.

DuSable had arrived in about 1772. In short order, and with the Indigenes’ explicit consent and permission, he quickly became well established and settled. That’s right. This black man, unlike the above-mentioned white men, actually asked permission first. He did not just move in and try to take over.

As the first “non-Indian” to permanently reside here, this black man is the one and only universally recognized “founder of Chicago.” Years later, one of the Pottawatomie chiefs said that the “first white man to settle in Chicago was a black man.” Indeed, Jean Baptiste Point DuSable sewed the seeds which ignited the development of what is now known as the City of Chicago. In 1800, DuSable sold his substantial holdings for $1,200 — a princely sum back then — and then moved to St. Charles, Illinois, where he died in 1815.

In 1818, Illinois was admitted into the Union as a “free” state. But slavery continued on a low key and undercover basis, while nominally “free” blacks were tightly controlled, indeed oppressed, by a series of restrictive state and local laws and ordinances that denied them fundamental rights and freedoms. Taken together, these pervasive Illinois Black Laws (also known as Black Codes) stayed in place and were rigorously enforced from 1819 until the very end of the Civil War in 1865.

The Black Codes of Illinois

The Black Codes included, but certainly were not limited to, the following:

* No black people (free or enslaved) could vote;

* Black people were barred from suing or testifying against white people;

* They could not meet in groups of more than three without risk of being jailed or beaten;

* Black people could not serve in the state militia. Not until the Civil War was there a standing national army and even then black people were not allowed to join the Union Army against the Confederacy until half-way through the Civil War — when it looked like the North might actually lose.

* Black people could be imprisoned for possessing or bearing arms — even for hunting purposes;

* Black people were barred from a whole array and entire classes of jobs and professions, and were not allowed to attend any so-called “public” schools;

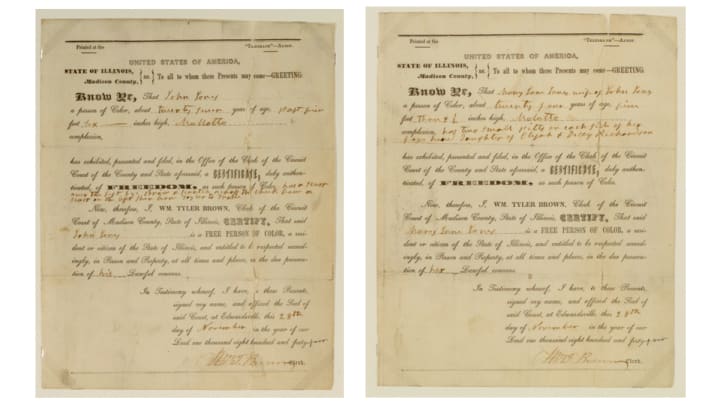

* All “free” black people in Illinois were required to obtain and carry on their person at all times a county-issued “Certificate of Freedom” (See below). If caught without their “Free Paper,” they were presumed to be slaves, and could be sold and shipped south “down the (nearby Des Plaines or Mississippi) river” into slavery.

* Considered as a more merciful alternative to outright enslavement, many free black people who had transgressed some element of The Code, were forced into indentured servitude at the salt mines in southern Illinois. These mines provided significant income for the state.

As noted, the Illinois Black Codes were finally and only repealed in 1865, with the passage of the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution, which ended slavery (save for convicted criminals).

(All of the northern states enforced similar or even more severe laws against free black people. Also, in the south where the slavocracy reigned supreme, there was another, even harsher, set of laws and rules and regulations set up and enforced against enslaved black people — “The Slave Codes”).

John and Mary Jones “Certificates of Freedom” (“Free Papers”). Image Credit: https://interactive.wttw.com/dusable-to-obama/early-chicago-slavery-illinois

John Jones

John Jones was a prominent Chicago businessman, an outspoken abolitionist, a “community organizer” in today’s parlance, and a tireless civil and human rights activist in Chicago. He came to local and national fame first as a committed leader in the protracted fight to repeal the above described Illinois’ Black Codes.

John Jones was born in 1817 in North Carolina to a free mulatto mother and a German-descended father ("white"). Because a child’s free or slave status followed that of his mother, Jones was born free.

He was trained as a tailor, and at 23-years-old, Jones moved to Chicago with his wife Mary Richardson Jones in 1845. They arrived in the “western” city of Chicago with just $3.50 between them. Neither John nor Mary had any formal education whatever and therefore both were illiterate. Still, Jones put his tailor training and skills to work and quickly developed a thriving tailoring business. He eventually began dabbling in real estate investments and gradually began to make real money. By 1860, John Jones was arguably the wealthiest black man in America.

John Jones, circa 1865. Image Credit:https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/jones-john-1817-1879/

Not long after his arrival in Chicago, Jones befriended local white abolitionists Charles V. Dyer (no relationship to yours truly), a physician, and an attorney, Lemanuel Covell Paine Freer. Freer taught Jones to read and write; and Jones took to reading as would a starving man to a hearty home cooked meal. Through his new found literacy, Jones further deepened and developed his business acumen and skills, and then put them to work in Chicago’s pivotal abolition movement. In 1864, he wrote and published a 16-page pamphlet entitled, "The Black Laws of Illinois and Why They Should Be Repealed."

Jones also worked indefatigably against the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which essentially deputized all white people everywhere in the country and required them to actively seek out and return runaway slaves to their southern masters. The Act imposed high fines on anyone who aided runaways or interfered with their capture; and it denied runaways the right to trial by jury, among other things.

In 1871, Jones was elected as the first black Cook County Commissioner.

John Jones died in 1879 at 62.

Mary Richardson Jones

In 1821, Mary Jane Richardson Jones was born free in Memphis, Tennessee. There, she met John Jones. Before their marriage, her family moved to Alton, Illinois and John soon followed. They married in 1844.

The couple decided to move to Chicago in 1845. While traveling to their new home, they were suspected of being runaway slaves and held for questioning; but the white stagecoach driver vouched for their status as free black people and they were allowed to continue on to Chicago.

Mary Jones was no less active in Chicago’s abolition circles than her husband. Her home at 119 Dearborn Street (now the booming heart of downtown Chicago’s famed “Loop”) was open to fugitive slaves anytime day or night; and was a regular meeting place — and safe house — for both escaped slaves and abolitionists alike.

Indeed, in 1955, the Jones’ granddaughter Theodora Purnell described Mary Jones’s role as a full and equal partner with her husband in this dangerous work:

She was mistress of the home where Nathan Freer, John Brown, Frederick Douglass and Allen Pinkerton visited. She harbored and fed the fugitive slaves that these men brought to her door as a refuge until they could be transported to Canada. In fact she stood at my Grand-father’s side — her husband John Jones — when their early Chicago home became one of the Underground Railway Stations. She it was who stood guard at the door when these pioneer abolitionists were in conference — with the slaves huddled below in her basement.

Mary Jones’ daughter described the family home a “haven for escaped slaves” and wrote that the family was personally responsible for helping hundreds of runaway slaves as they made their way through Chicago and on to real freedom in Canada.

And, Mary Jones was one of the original pioneers in the very first Women’s Suffrage Movement. In fact, she often hosted in her home Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Chatman Catt, Emma Chandler and Mrs. John Brown.

Mary Jones died in 1910 at 89.

John and Mary Jones were not pacifists by any measure. They hated slavery and did everything they could to end it. Speaking at a church in Chicago after the Fugitive Slave Act had passed in 1850, John Jones had this to say about how he and his wife would handle any runaway slave catchers who dared confront them as they went about their work in aiding escaped slaves:

We are determined to defend ourselves at all hazards, even should it be to the shedding of human blood. We who have tasted freedom are ready to exclaim in the language of the brave Patrick Henry, “Give us liberty or give us death.”

And so, of course Michelle and Barack Obama will feature prominently in the history books as a quintessential black American power couple.

But, by no means were they the first.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.