Knit One, Breathe One

How knitting helped me "hold space" when my Mom was dying and my world was unravelling

Knit 1, breath in. Purl 1, breath out.

When my mother was dying of cancer, I would sit by her side for hours at night, as she slept, keeping watch. I would knit in those empty hours, when the world was still and my focus shrank to the soft sound of my mother's breaths and the click-click of acrylic needles. Without thought, I would match my stitches to her breaths. Knit 1, breath in. Purl 1, breath out. As long as she was breathing, I told myself, she was still with us. I used a lot of moss (or seed stitch) as it was simple and repetitious, just alternating knit and purl. I worked on easy projects: cowls and scarves. No shaping, no increases and decreases. I had little energy for decisions or following directions. When my eyes drooped, and I started miscounting stitches, I would put my work down, and tip toe to bed.

Mum had been diagnosed with Stage-4 breast cancer. That's end stage, barring a new treatment. Or a miracle. Malignant cells have already been busy for some time travelling around the body, infecting other organs. By the time they detetected Mum's cancer, it was already in her bones. She had been hauling manure to her garden when a rib cracked. Her chiropractor felt her chest, said, "I don't like the feel of those ribs," and sent her for an X-ray. Her doctor said, "I don't like the look of your ribs," and sent her for a mammogram. When the results came back, her doctor, who was also a friend, cried in the office bathroom, before emerging to give Mum the bad news in an unsteady voice.

When Mum called to tell me, I couldn't take it in at first. I went to work in a daze, stumbling through the next few days with a sense of unreality. My life -- and the world as I knew it -- was unravelling. The person who had known me and loved me the longest and the most was leaving me. Mum had always been there in person or at the end of a telephone line to cheer my successes and commiserate with a broken heart ("he doesn't deserve you") or a failed job interview ("you'll find a better one"). We didn't always have a perfect relationship. We argued at times. We were both as stubborn as the other. But I hadn't realised until Mum got sick just how much she anchored me. Perhaps I took up knitting again in an effort to reweave the separating strands, to restore a familiar pattern in the face of the overwhelming sensation that my brother's and my lives were about to come apart.

Mom had a "scare" and went into hospital. My aunt flew up to Magnetic Island to be with her. She called me twice a day with updates. I took leave from work, packed a suitcase and got on a plane. So did my brother. When I arrived, Mom had rebounded but I think she knew she didn't have long.

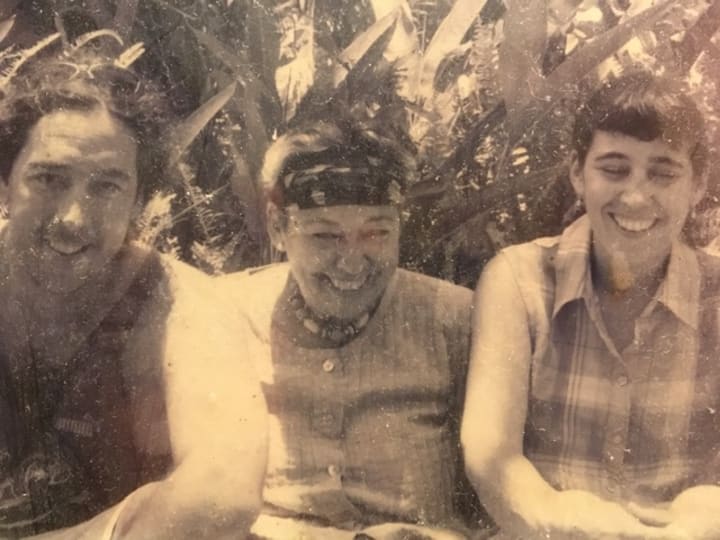

Mum's Island Home

Mum lived on Magentic Island, a small tight-knit community in Far North Queensland, that's half national park and beaches and half houses and summer cottages. The island is just off the coast of Townsville, and there are regular catamaran ferries, which take about 20 minutes each way. Most of the residents were over 55, retired, and everyone on the island knew about Mum. I'd walk into a shop or cafe and they'd ask, "How's Maggie doing?"

In Australia, 70% of older people want to die at home. But over 90% of them die in a hospital. Mom hated the thought of dying in a hospital. She'd almost done that, and alone. She disliked being awoken in the middle of the night to take pain medication, the constant beeps and whirring of machines, the echoing sounds of footsteps in halls, the intercom constantly paging doctors, the cleaning crew noisily arriving at dawn. She wanted to hear the trees in her garden creaking in the wind, the kookaburras calling to each other, the rain on the tin roof, and the distant surf. She wanted to sit on her back deck and feel the sun on her face.

Mom begged us to help her die at home. We'll figure it out, we said, my brother, my aunt and I. And we went about setting it up. We were lucky -- that's a word that I used a lot near the end, ironically -- that Mum only needed minor pain management and that she had two friends who were nurses who stopped in twice a day to change her drip -- and at the end, her urine bag -- and bathe her. The doctor and pharmacist made house calls. We had Meals on Wheels and a cleaner who came twice a week. There was a small supermarket on the island. I went for long walks to escape a too-small, crowded house filled with tense anticipation. Or I took the ferry over to Townsville to the library or the craft store. Choosing a new book to read to Mum or picking a texture and color of cotton or wool to knit was a welcome distraction. That was our world for weeks that turned into months.

Mum had a circle of women friends on the island. They embraced us as part of her, and left groceries on the front steps, or asked us out for coffee and a chat, or dropped in to "spell us" and sit with Mum so we could go for a walk, a swim or just out somewhere for some quiet time alone.

I stopped into the Townsville Palliative Care Center for support. They offered coffee circle meetings for carers, and advice about looking after your own health. I picked up a brochure with self-care tips. The woman at the desk thought knitting was a great idea. "It's good to keep your hands busy and give yourself something to focus on that you're doing just for yourself," she said. She herself crocheted.

I dragged myself through the days and collapsed into bed late at night, falling into dreamless sleep. I lost weight without even trying.

I couldn't write while Mum was dying. The words just wouldn't come. That act of creation requires energy and the kind of black hole focus that shuts everything else out and makes you lose track of time. I needed to stay present.

But I Could Knit

My grandmother taught me when I was seven. She came for a long visit from Australia to New Jersey, where we lived. She taught me to cast on, knit and purl. I started a bright red scarf. However, Gran went home without teaching me how to cast off, so my scarf grew and grew, until it was as long as Dr. Who's, and I ran out of yarn.

I picked up knitting again in college. I loved the way using a pair of needles and some yarn put me in a focussed, meditative trance and helped me to "knit out" a difficult problem or craft an essay in my head. If I was stuck or the creative juices had run dry, I'd put down the books and pick up the yarn. The solution always came, and the creativity always started to flow again. Using another part of my brain let the more logical or emotional parts get un-stuck. I was writing this essay, and the words stopped coming, so I picked up the cowl I'm making, sat in a chair and knit for a while. Suddenly, a new angle showed itself, so I put down the knitting and went back to the keyboard.

"Mindfulness, at its core, is about paying attention and being present in the moment. Substituting "knit one purl one" and adding the rythmic, repetitive hand motions of knitting can induce similar relaxed states as meditation, lowering heart rate and blood pressure, while engaging the mind and improving concentration," wrote Rachel Jacks in Apartment Therapy.

"I could never get into knitting," said Mum. "Your grandmother tried and failed to teach me." Mum was, however, a skilled needlewoman. She was a ballerina in the Royal Ballet in the 1950s and as "poor as a churchmouse." When the company travelled on long train journeys criss-crossing the Continent, Mum sewed all her own clothes and by hand: stylish Dior-look suits, blouses, swimwear and casual clothes, and darned her leotards and tights. While practical, it was also Mum's way of retreating into her own personal space in the midst of people she travelled, performed, practiced, socialized, and lived with.

While I was little, she made all my clothes, this time on a machine. She tried to teach me to embroider, but my French knots were bulky and lopsided, and my stitches were always uneven. My threaded leaves looked they were perpetually twisting in the wind.

The Night Watch

I'm so glad I chose knitting in those night vigils, as tired as I was, instead of joining the rest of the family in sleep. I was able to have last private conversations with Mum. I would read her to sleep (I thought) and then pick up my knitting. Suddenly, she'd speak when I hadn't realised she was still awake. If someone is reading a book, they don't seem interruptible. But if that same person is knitting, you feel comfortable speaking to them. Mum and I were in a bubble where we would continue to share quiet conversations for as long as we wanted, the outside world and time didn't intrude and death could not come. There were just softly-spoken words, pauses, the click-click of my needles, the rasp of the yarn and the soft sounds of Mum's breathing when she finally fell asleep.

"Look after your brother when I'm gone. He'll have a harder time than you will," she said once. "Of course," I said.

"I had to be sure," she said.

Another time: "It gives me comfort to die knowing that you and your brother will never go through this. "

"How can you know that?" I asked her.

"Because you've watched what I've gone through. So you'll go for tests every year, and if they find anything, it will be small and easy to treat. Like I wish mine had been."

Mum was right. I get three different tests every year.

One night she said, "It's a shame I won't get to hear the next book." I'd been reading her Tales of the Otari, a historical series set in feudal Japan. Mum loved the tale of a young warrior outwitting his enemies and winning against overwhelming odds. She said she needed a heroic story just then.

In our mid-night talks, I think Mum was telling me she was accepting her dying and perhaps testing me as well, to see if I might also be ready. Mothers always know their children best.

The Odyssey Scarf

Mum had lost her hair to the chemo drugs and her bare head was always cold. A friend had made her a hat in a variegated feather yarn that was popular at the time, in dark purple. Mum was feeling chilled to her bones towards the end, even in the tropical heat, so I decided to make a matching scarf for added warmth. I went to the giant craft store in Townsville and found the same yarn. I didn't need a pattern: I just cast on enough stitches to fit Mum's neck. I bargained and pleaded with the Universe in those still dark hours after she'd finally fallen asleep. Let her stay until her birthday. Let her stay until I finish the scarf. I started ripping out rows for the smallest mistake, for an uneven stitch, like Penelope in The Odyssey ripping out her weaving each night to delay completing it. (Mum died before I cast off and I never finished the scarf.)

The circle of women came together to support us, once again. They left casseroles on the front stoop so we didn't have to cook. They ran errands, or, if one of us was close to breaking point, quietly but persistently persuaded us out for tea and a chat. One friend, who ran a B&B, left a basket of croissants and pastries every morning at dawn.

I carried the memory of those mid-night talks and they comforted me.

Midwives Craft

Many years later, when I volunteered at a birth center in Bali as a doula, I learned that midwives usually carry craft projects to work on during "birth watches." That's while they're waiting hours and hours for the stages of labor to progress until the last one, as the baby descends, when things get really dynamic and the midwife's skills are urgently needed. Most of time spent at a birth ("labor-sitting") is simply waiting. Erin crocheted, a pale blue and white baby blanket growing under her hook. Robin makes jewelry, her fingers twisting knots between beads. A midwife from California did macrame. Others knit, sew, quilt or embroider.

"All midwives do some sort of craft," Robin told me, "Being a midwife requires that we "hold space" for the mother while she is laboring. We need to be close at hand and present in case she needs us." But it gets boring and tiring for a midwife, all that time piling up, and reading books doesn't really work as you get too distracted. You need to be able to speak or listen, if necessary.

Labor-sitting is when I learned the name of what I had been doing for my mother. I'd been "holding space" for her. It's a term from therapy and it means being physically, mentally and emotionally present for someone so they feel safe. "Sitting with someone in loving support can help them feel seen, understood and cared for," wrote therapist Tamara Turner. I wonder if I helped my mother to pass with more ease, knowing that crucial words had been spoken and heard.

"Holding space" can be seen as a sacred act. We "hold space" when a child is born and again when someone we love is dying. For me it's a form of prayer, of creating room for the sacred, outside of time.

At the birth center, I was once again part of a circle of women. I brought my knitting along when I labor-sat. It's peaceful sitting with other women outside a birth room, weaving a space for the mother and the new baby that is on the way, chatting sometimes, silent at other times, all ears listening for the closely-spaced groans and cries that indicate the third stage of labor has begun. The new mothers tell us after they felt supported and safe just knowing we were there for them. It brought me quiet joy to give back what other circles of women had given me.

We sat on benches, and chatted sometimes, and were silent sometimes. We crafted. Time passed. The noises of the birth center went on around us: a phone ringing occasionally, people talking and laughing in the office, motorcycles coming and going in the parking lot, kids running and shrieking somewhere close.

"Women often knit together companionably so that the work they do becomes at once individual and collective," wrote Susan Gordan Lydon in Knitting Sutra. I remember the knitting merged into the labor sitting merged into the sense of bonding.

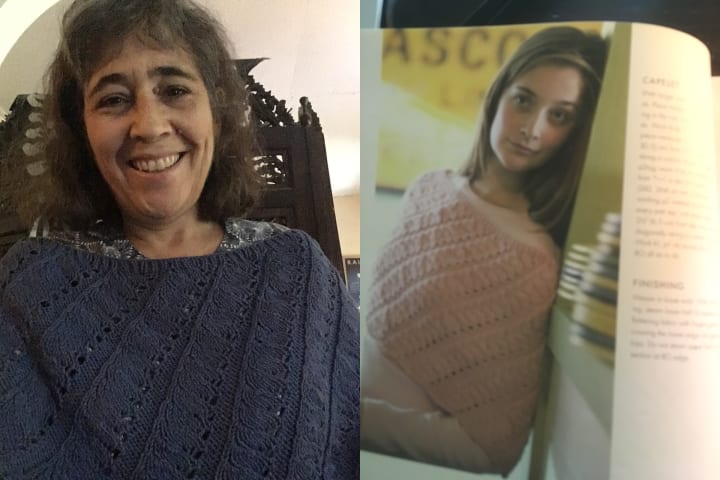

I worked on a lace shawl. I picked Deborah Newton's Spiral Shell Capelet pattern (from Wrap Style) and used balls of Debbie Bliss Cotton Cashmere (85% cotton, 15% cashmere) in a mid-dark blue from my yarn stash. Lace is still a repeating pattern -- just more elaborate -- which your hands learn to remember after a few rounds.

"Worked in rounds, a lace pattern has no beginning and no end," wrote Pam Allen and Ann Budd in Wrap Style, one of my favorite knitting books. Lace as meditation.

I'm sending my current projects -- cowls, scarves, socks, hats -- out into the world, to my own circle of friends, as a way to tell them I'm thinking of them right now during the pandemic and hoping they are safe and warm. The act of knitting comforts me as well.

So in these extraordinary and stressful times, I sit, and I knit, and I "hold space," this time for myself.

******

References:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-02/where-do-you-want-to-die-at-home-or-hospital/8584318

https://gstherapycenter.com/blog/2020/1/16/what-holding-space-means-5-tips-to-practice

The Knitting Sutra: Craft as a Spiritual Practice, by Susan Gordon Lydon

https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/why-knitting-is-the-best-form-of-mindful-meditation-240240

Wrap Style, by Pam Allen and Ann Budd

About the Creator

Liz Sinclair

Amateur historian who loves travel and lives in Asia. I write 'what-if' historical stories, speculative fiction, travel essays and haiku.

Twitter: @LizinBali. LinkedIn: sinclairliz

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.