Dostoyevsky's Demons

Stavrogin's Redemption Through Voluntary Suffering

In his political epic, Demons, Dostoyevsky introduces us to a man named Nikolai Stavrogin. Both mysterious and charming, he allures those around him by his very nature. However, we find that Stavrogin is merely a marionette. He has accepted the role of being the face of a revolution orchestrated by a man named Pyotr Verkhovensky. Stavrogin plays the role of an icon, a necessary ingredient for a revolution. He was the Stalin for the Soviet Union's new dawn, the Adolf for Germany's cleansing, the Trump for America's return to greatness, and the Floyd for BLM and Antifa's social justice looting.

Stavrogin is an enigma to the untrained eye. His persona is invariably attractive among the people. His isolation and mysterious background aid his appearance of strength. His reserved temperament makes him appear humble. In all estimations, he would be the cream of the crop as a mate. Oddly enough, we find he is married to a woman of low status; she is both mentally and physically disabled. The view of "heaven coming down to earth," so to speak, increases his stature even more in the public eye. How could anyone but a saint marry someone so beneath their worth?

Although Stavrogin is a part of Pyotr's revolution, it is apparent very early on that he shares little passion for it. In fact, his reasons for being a part of this coup de maître remain a mystery throughout the entire novel. To keep the plan alive, Pyotr must cautiously encourage, guide, manipulate, and chasten him. And while it is evident that Stavrogin's arm is being twisted, he appears to have nowhere else to go, nothing else of worth to do. The icon of the revolution is a shell. Like Caesar's Vegas Palace, the gold shimmers; the marble stands tall, but nothing in sight is bona fide.

Once the final coup has occurred, any meaning attached to Stavrogin disappears in the flames. No longer of use to Pyotr, he finds himself alone. With the city aflame, an outraged mob recognizes Stavrogin's wife and murders her. Stavrogin cannot bear his shame. Shortly after, he takes his life.

In an unpublished chapter, Stavrogin meets a monk named Father Tikhon. Dostoyevsky intended this exchange to occur before Stavrogin's involvement in the political scheme. The local magazine that was publishing his chapters every week disapproved of its content and required it to be scrapped from the novel.

The chapter opens with Stavrogin handing Father Tikhon a letter confessing one of his great sins. He tells the monk that he intends to submit the letter to the local newspaper and have it circulated as a means of seeking penance.

Several years prior, Stavrogin rented out several rooms around the city, one of which had a woman with a twelve-year-old daughter named Matryosha. Stavrogin had never taken notice of Matryosha until, one day, he saw her mother violently accusing her of misplacing a rag. The mother beat her abrasively in front of him. Shortly after, the mother found the rag underneath the kitchen tablecloth. Embarrassed for wrongfully punishing her child, but unwilling to apologize for it, she became even more frustrated when Matryosha made no fuss about it.

A few moments later, Stavrogin could not find his penknife. Still emotionally unsettled, the mother began beating Matryosha with a broom. It was at that moment that Stavrogin, for the first time, noticed the girl's "fair hair" and "freckled ordinary face." However, moments before the mother had even grabbed the broom, Stavrogin had found the penknife, but he said nothing and watched Matryosha's birching.

Pulling the monk's attention away from the letter, Stavrogin shares that he had always been emotionally void throughout his life. Very few instances could he recall an affect other than prosaic banality. Only in times of conflict, danger, or deliberate wrongdoing would he experience a sense of emotional arousal.

Stavrogin and Matryosha exchanged glances during her lashing. Something unspoken coupled them at that moment. Shortly before then, Stavrogin was considering ending his life. Yet, for some reason, he was prompted to endure. For what reason, he could not discern. He only knew he must avoid going to that house for some time.

A few days passed. Stavrogin found himself at the top of the stairs of the apartment. As he walked in, Matryosha noticed him and bashfully retreated to her room. They were alone. Stavrogin silently sat in the drawing room. After some time, he heard the girl's voice. She was singing. Inevitably, Stavrogin entered. Matryosha was timid, perhaps even afraid. He took her hand and kissed it. Nonplussed, she bashfully laughed. Again, he kissed her hand and placed her on his lap. As though ashamed, she turned away. Moments later, she wrapped her arms around him and passionately kissed him. Horrified, Stavrogin left without a word.

Oscillating from gayness to misery, from fear to homicidal hatred, Stavrogin was dismayed. The next morning, as he walked into the apartment, Matryosha ran from the room, screaming. Dumbfounded, her mother apologized for her strange behavior. Not knowing if Matryosha had told her mother of yesterday's events, animus filled his heart. Stavrogin tells Father Tikhon that not even his exile to Siberia caused such distress. At least for the moment, Stavrogin concluded that Matryosha's mother was unaware.

For several days, Stavrogin did not return. In the time away, he found himself taking notice of the house maid. He made efforts to woo her. He succeeded. The two left the city together. Stavrogin resolved to abandon his hometown, determined to put Matryosha behind him once and for all.

Having decided this, he returned to the city and informed Matryosha's mother. Overwhelmed with trepidation, she informed him that Matryosha had been in a state of delirium for three days. Warily, Stavrogin inquired if the girl had said anything during that time. Her mother told him that she continuously confessed that she had "killed God." Stavrogin offered to pay for her to see a doctor. She refused him.

Knowing that the girl's mother would be away at dusk, he resolved to return that night. Upon arrival, he saw the girl yet pretended he had not. He made an effort to lounge in a direction that was opposite her face. Contentment grew as he made her wait. After nearly an hour, Matryosha approached him. Her face had sunken. Although it had been only three days, she was emaciated. Outraged, Matryosha screamed at him. Emotionally numbed, Stavrogin missed every word. He only saw her dread; her facial expressions; so full of pain. Seeing such torment in a child crushed him. Try as he might, he knew there was no consoling her. Indignant, she left the room.

As though tied to his chair, he found himself unable to leave. An unconscious draw to stay culled; he was waiting for something. Another hour had gone by. Footsteps resounded. He saw her exit for the washroom. He paced the room frantically as he considered his options. Suddenly, he realized nobody had seen him when he entered the building. Strangely enough, he found comfort in this. Nearly twenty minutes of frenetic pacing went by. Struck with resolve, he ensured there was no trace of his visit, locked his bedroom door, and headed for the washroom. On tip-toe, he peeked through a crevice in the washroom door. With glazed eyes, and, having scratched his itch, he left. Hours later, Stavrogin was told that Matryosha hung herself.

Fully expecting complete condemnation from the monk, Stavrogin is dumbfounded to be met with a countenance of mercy. This unpublished chapter connected the dots of Stavrogin's peculiarities in a single confession. Stavrogin tells Father Tikhon that he unceasingly is haunted by visions of Matryosha; she appears in his dreams; she is there when he wakes in the morning. His rational understanding of hallucinations gives him no solace. Since his great sin, he has incessantly put his soul in a position to be tormented. As a means of vindication, he took on voluntary suffering. Whenever struck with a choice of selfishness, he chooses the most difficult thing. Meeting a downtrodden handicapped woman, he marries her. His past may be stained with blood, but perhaps he can wash himself with misery and self-sacrifice.

Ecstatic, the monk asks Stavrogin how he can say he does not believe in God.

“Listen, Father Tikhon: I want to forgive myself, and that is my object, my whole object!” Stavrogin suddenly said with gloomy ecstasy in his eyes. “Then only, I know, that vision will disappear. That is why I seek boundless suffering. I seek it myself. Don’t make me afraid, or I shall die in anger.”

The sincerity was so unexpected that Tikhon got up.

“If you believe that you can forgive yourself and attain that forgiveness in this world through your suffering; if you set that object before you with faith, then you already believe completely!” Tikhon exclaimed rapturously. “Why did you say, then, that you did not believe in God?”

Stavrogin made no answer.

“For your unbelief God will forgive you, for you respect the Holy Spirit without knowing Him.”

Dostoyevsky is one of the few authors that encapsulates my attention. His view of God is temerarious and borderline sacrilegious. At present, I cannot say I believe in God. At present, according to the doctrine I know, if the Christian God exists, I am destined for hell. How can Dostoyevsky make the claim that a non-believer could be graced with an opening of heaven's gates?

Suffering, voluntary suffering; holding an ideal; living according to the truth in the best way one can—could such a life be one that the Holy Spirit honors? Could any other life honor the Holy Spirit? Could it be true even if that individual explicitly rejects Him?

The twenty-first-century church has a view of God's mercy that I cannot accept. I see a weak inability to (refusal to?) demand any form of standard. To validate their complacency, they will often cite the story of Mary Magdalene—for even Jesus denied the casting of a stone. They use slogans such as, "Only God can judge," seemingly obvious to the fact that the rest of the world uses that verbiage to escape disapprobation for their misdeeds. In the name of compassion, they refuse to maintain accountability for failure, even toward their own congregation. Every moment is offered as a fresh start—a fresh start that has no bearing from the past. But this mercy—this unrestrained mockery of mercy—is a transgression of Christ's injunction to turn from sin and follow Him. Untrammeled mercy creates a swamp of recidivism. It germinates individuals who will convince everyone around them—perhaps even themselves—that they are sincere in their desire the change, all while making little to no reformation in their daily lives.

It is for this reason, clinical psychologist Dr. Jorbdan B. Peterson stated:

"[A] villain who despairs of his villainy has not become a hero. A hero is something positive, not just the absence of evil.

"But Christ himself, you might object, befriended tax-collectors and prostitutes. How dare I cast aspersions on the motives of those who are trying to help? But Christ was the archetypal perfect man. And you’re you. How do you know that your attempts to pull someone up won’t instead bring them—or you—further down?" (Jordan B. Peterson, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos)

The philosophy that the purest form of love is shown when it is given to people that least deserve it is contemptible and a bastardization of love itself. Love, true love, must require respect, it must stand up for one's self, or else the giver becomes the slave of the recipient. The recipient takes all that the giver has to offer until the well becomes dry, and neither of the two are the better from all that "kindness." Love must know when to say no. It must be capable of using its teeth to keep evil at bay. Love must refuse the tyrant his power and temper the tyrant within. Love must know boundaries, for without them, one cannot protect itself or others. Love is both the open door for the captive and the bulwark against the invader. Consequently, one must be able to differentiate between the two. It is for this reason that love must judge. Without it, the Trojan Horse is brought in, and the invader is mistaken as a gift. When the bloodshed comes, the good intentions of the lover will provide no protection: the walls intended to do so having been let down in the name of compassion.

To see when unlimited compassion turns into poisonous rot, look no further than the events of our time. In the name of giving people room to live their truth and the right to demand others play along, the tyrants have risen while those that can see the truth have gone underground. Even the oceans, in all their majesty, have a beginning and an end. The beauty of the shoreline would not exist if the whole world were covered in water. Though it is vast and abundant, the tide only goes so far before returning to its proper place—the pang of being told no when one sins is the shoreline of morality. Refusing to do so erodes the boundaries of the shore until the world is covered in water.

"But," you might say, "wouldn't the world covered in love be a wonderful place to be?" If, by love, you mean unlimited invasion of others and for others, then the answer is most certainly no. If, however, your conception of love includes the rights of both the giver and the recipient, a place where neither is given room to abuse the other and each voluntarily helps where the other needs, then the answer would, of course, be a resounding yes. This is where the argument lies. What is love? Which philosophy of love do you live by? Which philosophy of love promotes long-term well-being from both the giver and the recipient? Could love, whatever it may be, mean that which comes at the cost of another's life?

“'That’s your cruelty, that’s what’s mean and selfish about you. If you loved your brother, you’d give [what] he didn’t deserve, precisely because he didn’t deserve it—that would be true love and kindness and brotherhood. Else what’s love for? If a man deserves [something], there’s no virtue in giving it to him. Virtue is the giving of the undeserved...'

[H]e said slowly, '[Y]ou don’t know what you’re saying. I’m not able ever to despise you enough to believe that you mean it.'” (Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged)

Dostoyevsky claims that penance for one's sins is a sign of honoring the Holy Spirit. While such an attitude can become pathological, and the punishment in one domain may not correct for the errors of another, choosing to bear the weight of one's sins must be part of the road to redemption. When the modern church states that the weight of our sin is too great, so we, therefore, need a savior, it is, in my opinion, evil. What view of man must one have to believe that he is unable to bear the weight of his own life? What terrible pity must one have to claim that man cannot make things right, put things in better order than before, or redeem his past by becoming someone better in the present? It is not compassion that leads man to such conclusions but apathy, faithlessness, hopelessness, and an absence of love.

"You did not come down from the Cross when they shouted to you, mocking and teasing you: 'Come down from the Cross and we will believe that it is You.' You did not come down because again you did not want to enslave man with a miracle and because you thirsted for a faith that was free, not miraculous. You thirsted for a love that was free, not for the servile ecstasies of the slave before the might that has inspired him with dread once and for all. But even here you had too high an opinion of human beings, for of course, they are slaves, though they are created mutineers...

"Oh, we shall persuade them that they will only become free when they renounce their freedom for us and submit to us. And what does it matter whether we are right or whether, we are telling a lie? They themselves will be persuaded we are right, for they will remember to what 'horrors of slavery and confusion your freedom has brought them...

"Yes, we shall make them work, but in their hours of freedom from work we shall arrange their lives like a childish game, with childish songs, in chorus, with innocent dances. Oh, we shall permit them sin, too, they are weak and powerless, and they will love us like children for letting them sin. We shall tell them that every sin can be redeemed as long as it is committed with our leave; we are allowing them to sin because we love them, and as for the punishment for those sins, very well, we shall take it upon ourselves. And we shall take it upon ourselves; and they will worship us as benefactors who have assumed responsibility for their sins before God.

"And they shall have no secrets from us. We shall permit them or forbid them to live with their wives or paramours, to have or not to have children—all according to the degree of their obedience—and they will submit to us with cheerfulness and joy. The most agonizing secrets of their consciences—all, all will they bring to us, and we shall resolve it all, and they will attend our decision with joy, because it will deliver them from the great anxiety and fearsome present torments of free and individual decision. And all will be happy, all the millions of beings, except for the hundred thousand who govern them. For only we, we, who preserve the mystery, only we shall be unhappy." (Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov)

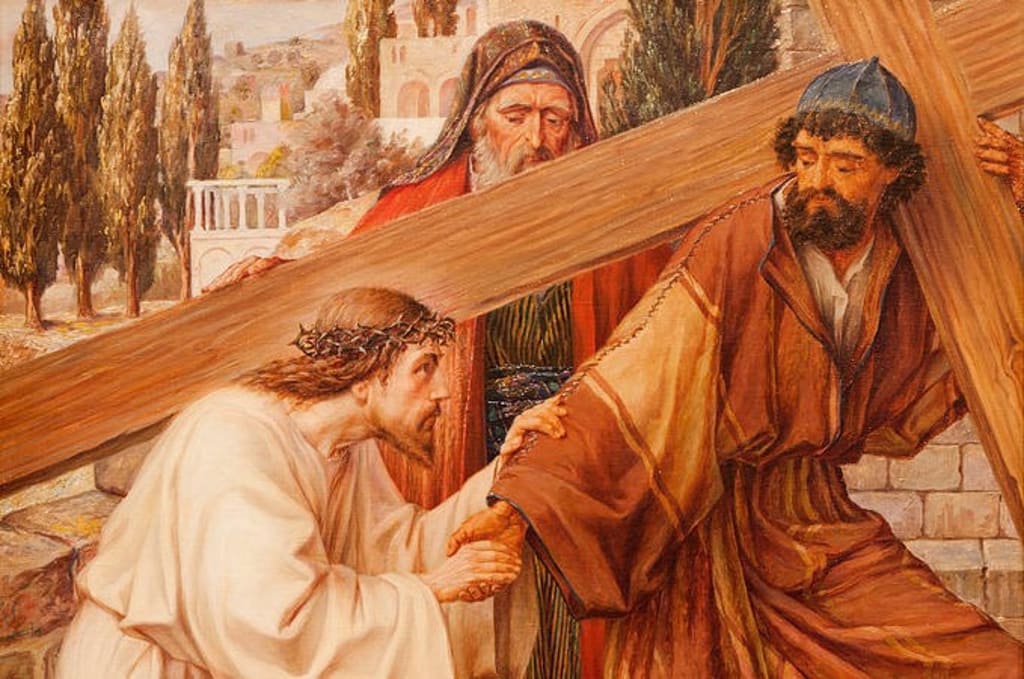

There is a profound difference between the God posited by Dostoyevsky and the God of the modern church. Dostoyevsky assumes a stance of continual repentance and the need to accept the weight of one's errors. The process of refining one's character and becoming someone who is no longer willing to commit such sins is redemptive—it is salvation. Today's church preaches forgiveness without the inherent suffering necessary to transform. Sure, you may have forsaken your cross, but you can always pick it back up. There will be no addressing the root of your character—no insistence on identifying what it was inside of you that led to the casting away of that cross. By ignoring such things—by refusing to point out your shame—you remain just as vulnerable to fail again. While there is much about the Christian doctrine that I disagree with, I can say, at the very least, the church is doing its congregants no good by remaining agnostic about their failures. Shame should not be used to bludgeon people into submission, nor should it be withheld to avoid offense.

For much of my life, I have been told that the standards I hold over myself are too high. My quandary is this: Should the standard be lowered simply because I have not attained it? Of course, there is utility in creating small-scale goals. But this practice is not for the sake of eliminating the ideal altogether. It is for the purpose of not losing hope along the way. And though my perspective of the ideal may change as I go, I find it dishonest and contemptible when I am told to let go of the ideal entirely for something more realistic. An ideal is a judge. If it were not above us, there would be nothing to aspire to. I will never attain its perfection. But pursue it, I must. Pursue it, we must. Every time we settle for less, the standard lowers, and we set our path down an infinite regression, where we will find our horizon constantly darkens until there is nothing but unlit skies.

Dostoyevsky's view of grace is one I can accept, as it is grace alongside the understanding of my wrongs. To be forgiven without comprehending what that forgiveness is for will do me no good. Unbound grace is the ferment of repeat offenders and parasites. "He that spareth his rod hateth his son: but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes." (Proverbs 13:24)

While he appears doctrinally heretical, I, for some reason, find hope in Dostoyevsky's message. Perhaps I am merely grasping onto an irrational hope for forgiveness if there is, in fact, a God. And while I do not anticipate a warm welcome when I die—I do not expect anything to happen at all—the sliver of my soul that believes hopes to find this God.

After Stavrogin's confession, the monk urges him to leave his public life behind and become an apprentice in a monastery. Defensive, Stavrogin belittles such a life as insignificant. Father Tikhon laments; he sees that Stavrogin is not ready for redemption. He tells Stavrogin, “[Y]ou, poor, lost youth, have never been so near another and a still greater crime than you are at this moment.”

Stavrogin mocks the old man and states that he might, in fact, postpone the letter's release. Tikhon corrects him, “No, not after the publication, but before it, a day, an hour, perhaps, before the great step [of releasing that letter], you will throw yourself on a new crime, as a way out, and you will commit it solely in order to avoid the publication of these pages.”

Days later, Stavrogin accepts a petition by Pyotr Verkhovensky to join a political revolution. His letter of confession is never released.

—GCF, April 28, 2023

About the Creator

Geno C. Foral

Husband of a beautiful wife. Father of a magical daughter. Student of clinical psychology.

Comments (1)

You are an amazing writer Geno! It is really interesting how you integrate your studies, emotions, thoughts and some experiences into your story. There are a lot of points being made in your story to talk about that it would be hard to post it all in this commemt. You have a beautiful heart for writing and a gentle soul to go about describing the good and the bad. I will just say this in short, I am trying to write this with many interruptions, so excuse me if I make a mistake. Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky is an interesting writer, I have never heard of him. But skimming through info about him and reading what you wrote about him, he seems to be theologically troubled, confused or misinformed with health problems, sent to a military insitution against his desires, abussive and losing himself a times. Biography from Frank, Joseph 1979 pp 114-15 When going broke he caught a break with his first novel "Poor Folk" from an influential litersry critic Vissarion Belinsky. Russians have the ultra orthodox version of Christianity and it is almost like Catholicism, but different and I am not sure if that impacted him. Grace I agree with you on abusing grace. That's not the goal of getting grace, grace is given to give us an opportunity to turn around from our ways and not a credit card to sin. As an ex-atheist and reading what God said about redemption, I understand why I can never redeem myself on my own. My actions once committed are done, they are irreversible. You can't delete the pain, scars and damage done to others or yourself. We can hide them in our memories, but it is a debt we cannot pay back. To remove one's sins is equal to cleaning an oil stain on your white shirt with your hands, you just spread it more. Sins/evil/wrongful actions are permanent stains to us and they only keep adding overtime. This is where Grace comes in from God, because He understands with wisdom about our inherited problem. But his grace is not an empty grace. It is a paid grace, where those whose are wronged are given justice and those who are forgiven, their debt paid by the Son of God. We live in a much more fallen world than a decade ago, everyone is losing their minds. Whites are blamed for no reason, Men cannot be man, Women want to be man and vice versa. Children are indoctrinated and exposed to sexual content. The corruption of this nation gets higher and the mainstream news is orchestrated to manipulate the people. Satan is glorified and Jesus Christ is villanized. We have been living in the U.S as a majority anti-christ controlled nation and things have only gotten worse since these new management took over. I am not bringing politics, but an example of how powerful and visible it is to see a Nation with God and one without. The less we have of God, the worse we become as a society, there is less love. There is no self accountability from one another. One's person morals are not the same as the other. There is no moral compass without God. One day, one tribe, one nation may consider it okay to kill another for their benefit and that is their moral. Another is satisfied with stealing. Kidnapping etc. But with God (Jesus Christ) we have a universal moral law that never changes that teaches us to love one another with respectable boundaries and given the Holy Spirit to help us overcome the evil in us and have self control. Of course there us much more. Anyways, you are an amazing writer, love it. I hope to run into you one day!