The South China Sea Dispute: A History of the Conflict

A small outcrop of sand occasionally disrupts the endless expanses of the South China Sea. These islands are modest, even miniature, but they lie at the heart of a fierce territorial dispute among six major claimants: Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. These claimants also conflict over their rights and obligations in the adjacent waters and the seabed beneath them.

The disputes in the South China Sea have the potential to ignite a broader regional conflict. Numerous claimants argue over sovereignty issues that are not easily resolved legally. Worse still, the stakes are high: the sea is one of the main routes of international trade, and many claimants believe that, in addition to rich fish stocks, the sea hides generous oil reserves. The disputes are further exacerbated by rampant nationalism, as each side assigns symbolic value to the islands of the South China Sea far exceeding their objective material wealth. Finally, the disputes are also colored by great power politics, as China and the United States push each other for control over the international order.

Over the past year, disputes in the South China Sea have dominated the headlines, and they seem likely to continue to generate new national security challenges. They have already raised a host of legal issues that will impact the future development of both the conflict and the region as a whole.

Accordingly, Lawfare has decided to prepare a reference on the South China Sea, consisting of two parts. First, in this part, I will outline the history of the disputes and highlight key events necessary to understand the current crisis. In the second part, I will present the main legal issues underlying the disputes.

Centuries of Contested History

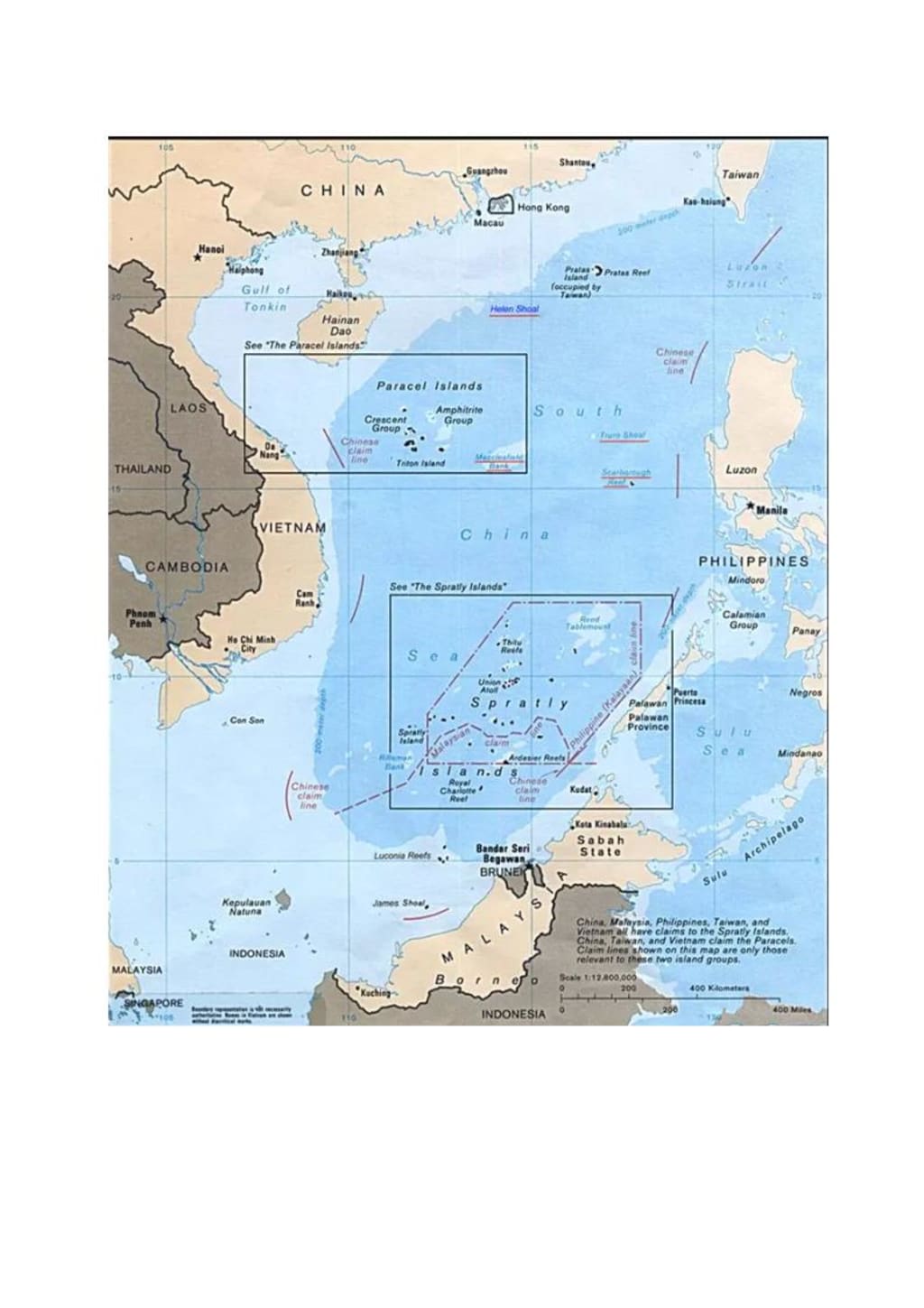

The South China Sea with highlights of the Paracel Islands and the Spratly Islands. As readers can see on the map above, the islands of the South China Sea can be grouped into two island chains. The Paracel Islands are located in the northwestern corner of the sea, and the Spratly Islands are in the southeast.

Reflecting the Rashomon-like nature of the dispute, the claimants have fiercely argued about the "true" history of these island chains. Some attempt to justify their contemporary claims by arguing a long and continuous history of national control over the disputed territories. These states claim, for example, that their citizens have fished around the islands or used them as shelter from storms. Beijing, in particular, is actively subsidizing archaeological excavations to find evidence of China's exclusive use of the sea's numerous resources since time immemorial.

It is difficult—if not impossible—to wade through these biased claims (many of which are pure propaganda). No impartial tribunal has yet taken on this task. However, to the extent that any conclusions can be drawn from this confusion, it seems fair to say that none of the claimants has convincingly demonstrated a pattern of exclusive historical control over the South China Sea or even over its isolated parts.

A Period of Relative Calm

In any case, this issue was moot for most of the region's history. During the first half of the twentieth century, the sea remained calm as neighboring states focused their attention on conflicts unfolding elsewhere.

In fact, by the end of World War II, none of the claimants occupied any islands in the entire South China Sea. Then, in 1946, China established a presence on several parts of the Spratlys, and in early 1947, it also seized Woody Island in the Paracel chain just two weeks before the French and Vietnamese intended to land there. Abandoning their first choice, the French and Vietnamese settled on the nearby Pattle Island.

Even at this stage, however, the South China Sea was not considered a priority for any of the claimants. Thus, when Chiang Kai-shek's troops retreated to Taiwan after their catastrophic defeat by Mao's communists, they left their positions in the South China Sea. Even the French and Vietnamese did not bother to take advantage of the Chinese withdrawal, as they were preoccupied with the rapidly escalating war in Vietnam.

Claimants to Control

Interest in the South China Sea, however, grew over the next half-century. In 1955 and 1956, China and Taiwan established a permanent presence on several key islands, while Filipino citizen Thomas Cloma claimed much of the Spratly island chain as his own.

Again, this phase of frantic island occupation was cooled by a longer period of inertia. But in the early 1970s, countries again took up the cause. This time, however, the impetus was signs that oil might be hiding under the waters of the South China Sea. The Philippines were the first to cast an eye on it. Soon after, China followed, conducting a carefully coordinated naval invasion of several islands. In the battle for the Paracels, it wrested several parts from South Vietnam's control, killing several dozen Vietnamese and sinking a corvette in the process. In response, both South and North Vietnam reinforced their remaining garrisons and occupied several other unclaimed territories.

Another decade of relative inactivity was again interrupted by violence in 1988, when Beijing took the Spratlys and began another round of occupation. Tensions peaked when Beijing forcibly occupied Johnson Reef, killing several dozen Vietnamese sailors in the process.

However, tensions again subsided for several years, only to rise again in 1995 when Beijing built bunkers over Mischief Reef in response to a Filipino oil concession.

Diplomatic Developments

It seemed that the dispute took a turn for the better in 2002 when ASEAN and China came together to sign the "Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea." The Declaration aimed to create a framework for possible negotiations on a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea. The parties pledged to:

Exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability, including, among others, refraining from actions of inhabiting on the presently uninhabited islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features and to handle their differences in a constructive manner.

For a time, the Declaration seemed to ensure peace in the region. Over the next half-century, Beijing began a diplomatic offensive in Southeast Asia, and claimants refrained from provoking each other by seizing additional territory.

Instead of engaging in naval battles, the claimants began to trespass on each other with demarches and verbal notes. In May 2009, Malaysia and Vietnam sent a joint submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, outlining some of their claims. This initial submission triggered a flurry of verbal notes from other claimants disputing the two countries' claims.

Notably, in response to the joint submission, China provided a map containing the infamous "nine-dash line." This line snakes around the edges of the South China Sea and encompasses all the sea's territorial features and most of its waters. However, Beijing has never officially clarified what this line is meant to signify. Instead, it maintains "strategic ambiguity" and simply states that:

China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil (see map).

This may mean that China claims only the territorial features in the sea and any "adjacent waters" permitted by maritime law. Or it may mean that China claims all the territorial features and all the waters bounded by the nine-dash line, even those beyond what maritime law permits.

Recent Crises

Since the disclosure of the nine-dash line, there has been growing concern in the region about China's plans in the South China Sea. In 2012, Beijing confirmed some of these concerns by seizing Scarborough Shoal from the Philippines. The two states argued over allegations of illegal poaching by Chinese fishermen. After a two-month standoff, the parties agreed that each should withdraw from the shoal. Manila did so. Beijing did not. Since then, China has blocked Filipino boats from the shoal's waters.

In response to this escalation, Manila filed an arbitration case against China on January 22, 2013, under the auspices of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The Philippines' claims concern maritime law issues, although China argues that they cannot be resolved without first addressing territorial issues. For this reason, Beijing has largely refused to participate in the proceedings, although it has prepared and published a position paper contesting the tribunal's jurisdiction. The Philippines submitted its memorial, along with a rebuttal to China's position paper, and both countries now await the tribunal's decision on its jurisdiction.

As the case continues, China has taken an increasingly assertive stance in the region. In early May 2014, a Chinese state oil company moved one of its drilling rigs into waters claimed by Vietnam, south of the Paracels. This provocation sparked confrontations between Vietnamese and Chinese ships around the rig, as well as anti-foreign business riots in parts of Vietnam. Faced with such opposition, China withdrew the rig in mid-July, a month earlier than planned.

Additionally, over the past year, Beijing has launched an accelerated land reclamation campaign in the South China Sea. At least seven locations have seen Chinese ships dump tons of sand to expand the size of China's occupied territories. Beijing has also begun constructing infrastructure on most of these reclaimed lands, including a runway capable of accommodating military aircraft. While other claimants have reclaimed land in the past, China has reclaimed 2,000 acres of new land, more than "all other claimants combined throughout their history of claims," according to U.S. Department of Defense data.

Other claimants have condemned this latest project as counterproductive, and President Obama has called on China to stop "throwing elbows and pushing people out of the way" in pursuit of its interests. So far, Beijing has not heeded these calls, and it remains unclear what the next turn in the history of the South China Sea will be.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.