Pre-Islamic Arabia

WHAT WAS TRIBAL ARABIA LIKE UNTIL THE BEGINNING OF ISLAM?

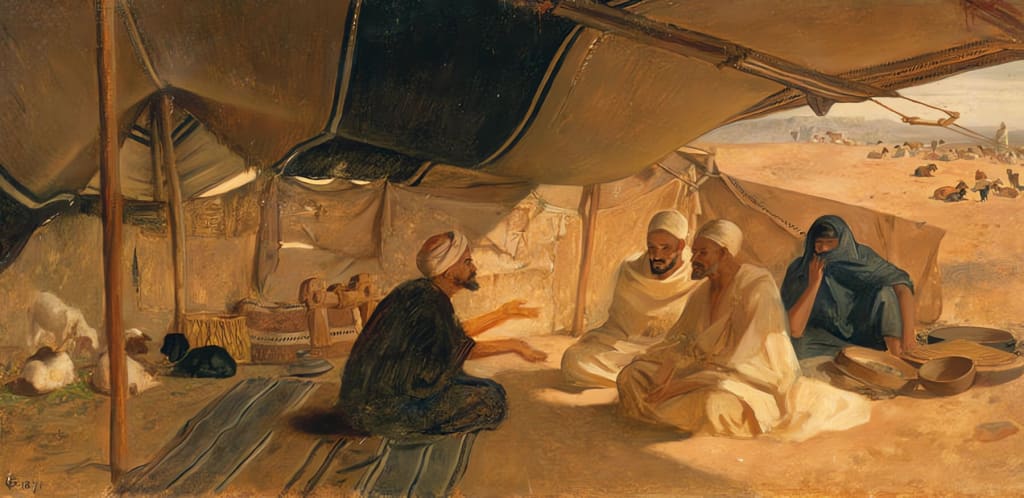

The Arab world prior to the emergence of Islam was a sprawling territory inhabited by numerous nomadic and settled tribes, each with its own distinct culture. These tribes existed independently of one another, lacking any form of cohesion or unity. Present-day Muslims commonly refer to this period as the "jilia" or pre-Islamic era of Arabia. It is important to note that the concept of Arabia or the Arab world during this time is not based on geographical boundaries, but rather a modern construct. The amalgamation of various tribes in pre-Islamic Arabia, despite possessing minimal cultural similarities, can be likened to the situation with the Celts. The term "jilia" was used pejoratively by Muslims to describe the era of ignorance, during which the Arabs were believed to engage in destructive and sinful behaviors such as gambling, alcohol consumption, usury, and fornication, in addition to practicing polytheism. Similarly, the Dark Ages and the Middle Ages were terms coined during the Renaissance to denigrate the medieval period in Europe. However, our understanding of the pre-Islamic era primarily relies on legends and poems, as written sources from that time are scarce. Islamic sources, such as the Quran and the Radit, also provide information about this period, although they are often criticized for their biased portrayal of pre-Islamic Arabia. Despite these limitations, the available information allows us to gain insights into the lives of the pre-Islamic tribes in Arabia. These tribes were organized along tribal lines, with each tribe being named after its esteemed leader, similar to the dynasties of medieval Europe. Within these tribes, smaller family groups known as clans existed, often engaging in fierce competition for control. However, in the face of external threats, the clans would set aside their disputes and unite against the common enemy, mirroring the behavior of the Celts when confronted with the invasions of the Roman Empire. These clans were led by individuals known as "shakes," who were selected based on their age, generosity, and courage. These leaders held positions of authority within a council responsible for making important decisions and judgments. In instances where conflicts arose between tribes, the clan councils convened to seek resolutions. It is important to note that during the Pre-Islamic period, there were no established laws, resulting in arbitrary judgments and the potential for bribery. In tribal councils, individuals with influential connections often escaped punishment, highlighting the prevalence of biased judgments. Additionally, it was common for aggrieved parties to take matters into their own hands rather than seeking justice through the tribal court system. This was likely due to the understanding that they would likely lose their case, particularly if the dispute involved members from different tribes. In such instances, the accused, if belonging to a more powerful tribe, would often evade punishment. Conversely, the most powerful tribes held authority over various territories, akin to medieval European kingdoms. These territories encompassed cities, towns, and even smaller settlements consisting of local tents, with access to essential resources such as water, pastures, and cultivable land. Despite the perception of desert lands in Arabia as insignificant by ancient empires, the tribes inhabiting the region were not entirely excluded from major political engagements. The Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, representing the Eastern Romans and the pre-Islamic Persians respectively, utilized Arab tribes as vassals, allies, and clients to safeguard their southern borders. Arab forces were integrated into the armies of both empires and occasionally clashed with each other on the battlefield. However, historical records indicate instances where Arabs refused to engage in warfare against fellow Arabs, demonstrating a sense of communal solidarity that would later become significant. The foundation of Islam was established on the principles of equality and justice. However, in certain circumstances, tribes within Arabia would form alliances with foreign powers if they believed it would lead to victory in conflicts with other tribes. Occasionally, empires would even launch military campaigns in Arabia to seek revenge or conquer territory. Nevertheless, due to the harsh arid conditions and the fierce resistance of the Arab tribes, these invaders were typically expelled within a few years.

Trade played a vital role in the lives of the Arab tribes, serving as their primary means of connecting with the outside world. Caravans would travel to markets in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Ethiopia, trading goods such as leather, dried fruits, and silver. The return of these caravans with profits was cause for celebration, as the Arabs heavily invested in these ventures and reaped excellent returns. It is believed that through these commercial caravans, the Arab tribes first encountered medieval Germanic tribes and Christianity, particularly from the 5th and 6th centuries onwards, when the importance of caravans grew even further. This was due to the increasing dangers of sea routes caused by wars and piracy, which made the Arab tribes controlling the land routes wealthier and more influential. To facilitate trade, seasonal markets were established at various locations throughout Arabia, attracting Arabs from all corners of the peninsula to engage in business transactions. These markets also served as platforms for poets and missionaries to engage in debates and address the crowds. Additionally, these markets facilitated the buying and selling of slaves, as well as the operation of moneylenders who profited from charging exorbitant fees. Consequently, the practice of usury led to a widening wealth gap, with the moneylenders amassing riches while those who borrowed money became increasingly impoverished. It was within this context of growing inequality that Islam gained prominence, as its religious philosophy stood against such exploitative practices. Before the establishment of Islam as the dominant religion in the Arabian Peninsula, the people were predominantly polytheistic, with various clans and families worshiping different deities. In addition to the polytheistic beliefs, there were also small Christian and Jewish communities living in towns and cities. The diversity of deities was exemplified by the people of Mecca, who worshiped up to 360 deities. However, with the emergence of Islam, the practice of polytheism was prohibited, and all statues were destroyed. Despite the religious shift, the poetry from that time was highly valued and preserved by Muslims for several centuries. It is worth noting that women were not allowed to hold leadership positions or participate in wars, but they were permitted to be poets. Some settled communities in ancient Arabia developed into distinct civilizations, although information about these communities is limited. Our understanding of these civilizations has been pieced together from various sources, including archaeological evidence, accounts written by individuals outside of Arabia, and oral traditions passed down by Arab communities and later recorded by Islamic historians. Among the most notable civilizations were the Thamud civilization, which emerged around 3000 BCE and lasted until around 300 CE, and the Dilmun civilization, which was the earliest Semitic civilization in the eastern part of Arabia and existed from the end of the fourth millennium BCE until around 600 CE.

Furthermore, starting from the second half of the second millennium BCE, Southern Arabia became home to several kingdoms, including the Sabaeans and Minaeans. In Eastern Arabia, Semitic speakers, believed to have migrated from the southwest, inhabited the region, including the so-called Samad population. From 106 CE to 630 CE, northwestern Arabia was under the control of the Roman Empire, which renamed it Arabia Petraea. Additionally, certain key areas in Arabia were controlled by the Iranian Parthian and Sassanian empires. The Red Sea and Indian Ocean trade brought prosperity to many small kingdoms. Among the major kingdoms were the Sabaeans, Awsan, Himyar, and Nabateans. The earliest known inscriptions of the Kingdom of Hadhramaut date back to the 8th century BC. It was referenced by an external civilization in an Old Sabaic inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BC, where the king of Hadramaut, Yada'il, is mentioned as one of their allies. Dilmun first appears in Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets dating back to the late 4th millennium BC, found in the temple of the goddess Inanna in the city of Uruk. The adjective Dilmun refers to a type of axe and a specific official; in addition, there are lists of wool rations issued to people connected to Dilmun. The Sabaeans were an ancient people who spoke an Old South Arabian language and lived in what is now Yemen, in the southwest of the Arabian Peninsula, from 2000 BC to the 8th century BC. Some Sabaeans also lived in D'mt, located in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, due to their hegemony over the Red Sea. They lasted from the beginning of the second millennium to the 1st century BC. In the 1st century BC, they were conquered by the Himyarites, but after the disintegration of the first Himyarite Empire of the kings of Saba and Dhu-Raydan, the Sabaean Kingdom reappeared in the early 2nd century. It was finally conquered by the Himyarites in the late 3rd century.

The ancient Kingdom of Awsan, with a capital in Hagar Yahirr in the Markha gorge, south of the Bayhan gorge, is now marked by a saying or artificial mound, which is locally named Hagar Asfal. It was one of the most important small kingdoms of South Arabia. The city appears to have been destroyed in the 7th century BC by the king and mukarrib of Saba, Karib'il Watar, according to a Sabaean text that reports the victory in terms that attest to its significance for the Sabaeans. The Himyar, an ancient state in South Arabia, emerged in 110 BC and expanded its territory by conquering Qataban in approximately 25 BC, followed by Hadramaut in around 300 AD. The political dynamics between Himyar and the Sabaean Kingdom were characterized by frequent fluctuations until Himyar's ultimate conquest of the Sabaean Kingdom in 280 AD. Himyar maintained its dominance in the Arabian region until 525 AD. The foundation of its economy rested on agriculture, while foreign trade thrived through the exportation of frankincense and myrrh. Notably, Himyar played a crucial role as a key intermediary, facilitating trade between East Africa and the Mediterranean world. This trade primarily involved the export of ivory from Africa to be traded within the Roman Empire. Himyar's maritime activities extended to regular voyages along the East African coast, and the state exerted significant political influence over the trading cities in East Africa. The origins of the Nabataeans remain unclear. Jerome proposed a potential connection between the Nabataeans and the tribe Nebaioth mentioned in Genesis, based on similarities in sounds. However, contemporary historians exercise caution when discussing the early history of the Nabataeans. The Babylonian captivity, which commenced in 586 BC, created a power vacuum in Judah. As Edomites migrated into the grazing lands of Judah, Nabataean inscriptions began to appear in Edomite territory. This occurred prior to 312 BC, when they faced an unsuccessful attack at Petra by Antigonus I. The first definitive mention of the Nabataeans occurred in 312 BC, when Hieronymus of Cardia, a Seleucid officer, referenced them in a battle report. In 50 BC, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus cited Hieronymus in his report and added that the Romans, like the Seleucids before them, made several attempts to gain control of the lucrative trade associated with the Nabataeans.

Petra, also known as Sela, served as the ancient capital of Edom. It is likely that the Nabataeans occupied the former Edomite territory and inherited its commercial activities after the Edomites took advantage of the Babylonian captivity to expand into southern Judaea. The exact date of this migration is unknown. Additionally, this migration allowed the Nabataeans to gain control over the shores of the Gulf of Aqaba and the significant harbor of Elath. According to Agatharchides, they caused trouble for a period of time as wreckers and pirates, disrupting the trade between Egypt and the East. Eventually, they were disciplined by the Ptolemaic rulers of Alexandria. The Lakhmid Kingdom, established by the Lakhum tribe, originated from Yemen and emerged in the 2nd century. Governed by the Banu Lakhm, the kingdom derived its name from this ruling family. Comprised of Arab Christians residing in Southern Iraq, the Lakhmid Kingdom designated al-Hirah as its capital in 266. 'Amr, the founder of the dynasty, witnessed the conversion of his son, Imru' al-Qais, to Christianity, which subsequently led to the gradual adoption of this faith by the entire city. Imru' al-Qais envisioned a unified and independent Arab kingdom, and in pursuit of this aspiration, he conquered numerous cities in Arabia.

The Ghassanids, a collection of South Arabian Christian tribes, migrated from Yemen to the Hauran region in southern Syria, Jordan, and the Holy Land during the early 3rd century. During their settlement, they intermarried with Hellenized Roman settlers and Greek-speaking Early Christian communities. The oral tradition of southern Syria has preserved the account of the Ghassanid emigration. According to this tradition, the Ghassanids originated from the city of Ma'rib in Yemen, where a dam existed. However, due to excessive rainfall in a particular year, the dam was destroyed by a subsequent flood, compelling the inhabitants to seek refuge elsewhere. Consequently, the emigrants dispersed across various regions in search of more fertile lands. The saying "They were scattered like the people of Saba" alludes to this historical exodus. The emigrants belonged to the Azd tribe of the Kahlan branch within the Qahtani tribes.

About the Creator

A História

"Hi. My name is Wellington and I'm a passion for general history. Here, I publish articles on different periods and themes in history, from prehistory to the present day.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.