Labor Day - An Origin Story

“We struck at Pullman because we were without hope. We joined the American Railway Union because it gave us a glimmer of hope.” ― From a statement the Pullman workers delivered at the union's convention at Uhlich Hall in Chicago.

Labor Day is a great way to get a three-day weekend. It's an American holiday celebrating the social and economic achievements of American workers so what's not to love? Oh the barbecues, the sunny afternoons, and the fireworks! Having said that, the truth is, Labor Day was given to laborers during a strike that was likely to shut down the railroad. It had its humble beginnings as a Civil Rights movement, one that many have forgotten about.

In 1867, George Pullman organized the "Pullman Palace Cars". Though not really affiliated with the railway, what George planned to do, was create sort of a fleet of luxury hotels, via rail car. In fact, prior to becoming an organization, in 1863, he began work on a special palace car for the president, Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln felt the car too lavish and never used it while he was alive. However, it was used by the Lincoln family to deliver his body to each stop on the line, enroute to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois. (I wrote an earlier piece about the journey of Lincoln's body with his son Robert Todd. Taking several days, the journey covered over sixteen-hundred miles. The article about that is entitled "Threnody in Steam" and you can read it here.)

George Pullman began his business well intended enough but the world was changing and his company was struggling to change with it. After the Civil War, the positions of "Porter" had been sought after by the African American community because they offered a livable wage and benefits, and George Pullman was one of the few people hiring them.

Still, the porters who served in the sleeper cars were all referred to by the passengers as “George”. This was unfortunately a tradition begun in the South where most slaves were called by the name of their masters, and sadly, a tradition that lasted for over 60 years. Under George Pullman, the cars were always integrated, something the company prided itself on. While Pullman didn't begin the tradition of calling the porters George, nor did he condone it, he never did anything about it either.

The porter on George's sleeper cars may have been considered a good position in the beginning, but the definition of their job was steeped in contradiction. The porter had the best job in his community and the worst job on the train. He could be trusted with his white passengers' children and their safety, but only while traveling. He shared his riders' most private moments but, to most, remained an enemy at the end of the line. Porters worked under the supervision of a Pullman conductor (distinct from the railroad's own conductor in overall charge of the train), who was invariably white.

As time wore on, wages dwindled and many of the workers were living in slum conditions, as they rented from Pullman, and they paid exorbitant rates so that the company practically owned them. By the early twentieth century, the jobs for the Pullman Palace Cars were no longer considered "good jobs" for African Americans.

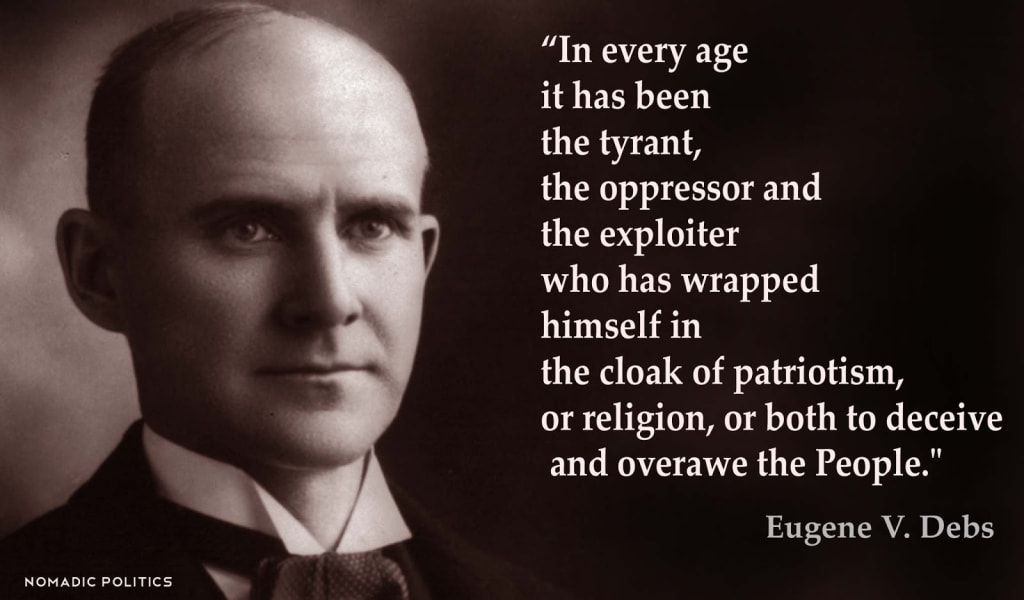

In the background of all this, member of the Socialist Party of America, Eugene V. Debs, was organizing railway labor unions. While the railway strike of 1877 failed, Debs was successful in founding the American Railway Union (ARU), one of the nation's first industrial unions.

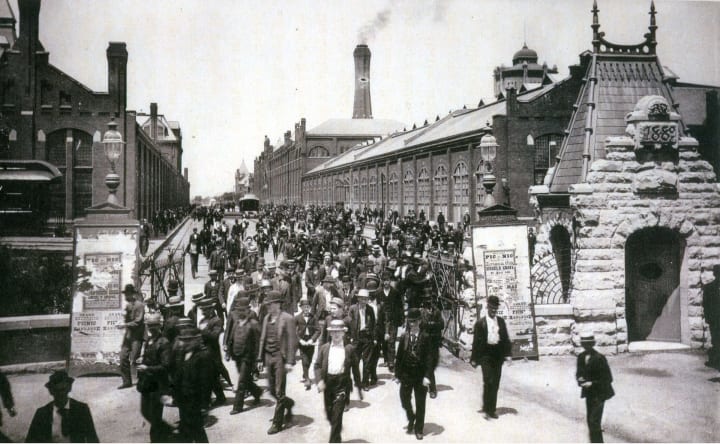

During an economic depression in 1893, Pullman Palace Car employees suffered wage decreases of 28% across the board. Working hours were increased and jobs cut. George Pullman refused to negotiate so, on May 11, 1894, workers walked off the job.

After they walked out, Eugene Debs signed many of them into the ARU. He led a boycott by the ARU against handling trains with Pullman cars in what became the nationwide Pullman Strike, affecting most lines west of Detroit and more than 250,000 workers in 27 states. With the ARU agreeing to assist the Pullman workers, switchmen who were members of the ARU refused to handle Pullman cars, which disrupted the entire rail network and led to widespread strikes among the nation’s railroad workers as a whole.

There were damages to railroad properties as a result, and among them was a locomotive attached to a U.S. mail railcar. Mail wasn't getting sent by rail either, due to the strike. Since the protest had affected federal government business, U.S. President Grover Cleveland and his cabinet used that as a reason to get involved in the strike.

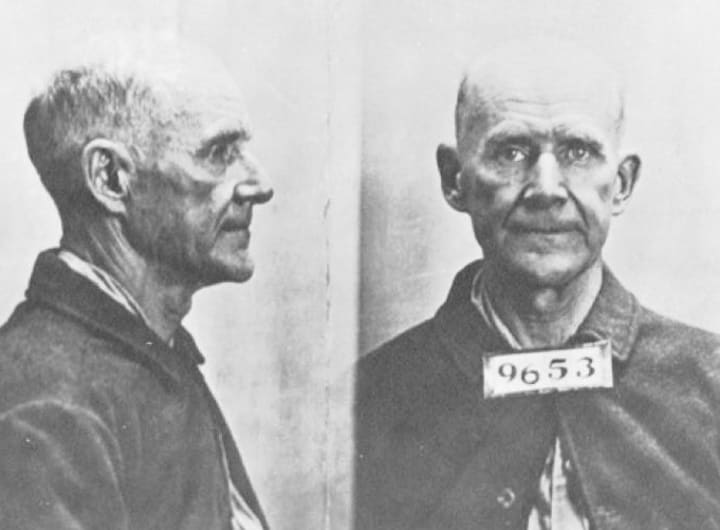

Attorney General Richard Olney obtained an injunction against the ARU, which only stood to fuel the railway workers even more. The growing anger ended in violence at a gathering of workers in Blue Island, Illinois because President Cleveland sent in federal troops to handle strikers, which ultimately led to the violence. As a leader of the ARU, Debs was convicted of federal charges for defying a court injunction against the strike and served six months in prison.

Railway companies started to hire nonunion workers to restart business, and by the time the strike ended, it had cost the railroads millions of dollars in lost revenue and upwards of 80 million in damaged property. Striking workers had lost more than $1 million in wages and overall, thirty strikers were killed in the strike, thousands blacklisted.

Pullman workers largely lost the sympathy of the public as well, with many anxious about outbreaks in violence as well as disruptions in rail traffic. The mainstream press criticized Debs and labor in general. In fact, due in part to the strike, Jim Crow laws were passed in 1900 necessitating the segregation of Pullman cars when on southern soil. Pullman Palace Cars, a business that began as an unsegregated company, was now mandated to remain segregated in certain areas, over 35-years after the war. The Jim Crow tradition remained unbroken when George Pullman passed in 1897, and Robert Todd Lincoln assumed the presidency of Pullman's empire.

President Cleveland and Congress did make one conciliatory gesture toward the labor movement during the strike, however. The strike prompted Cleveland to propose a bill to make Labor Day a national holiday. Cleveland signed the bill into law on June 28, 1894.

The Pullman Porters?

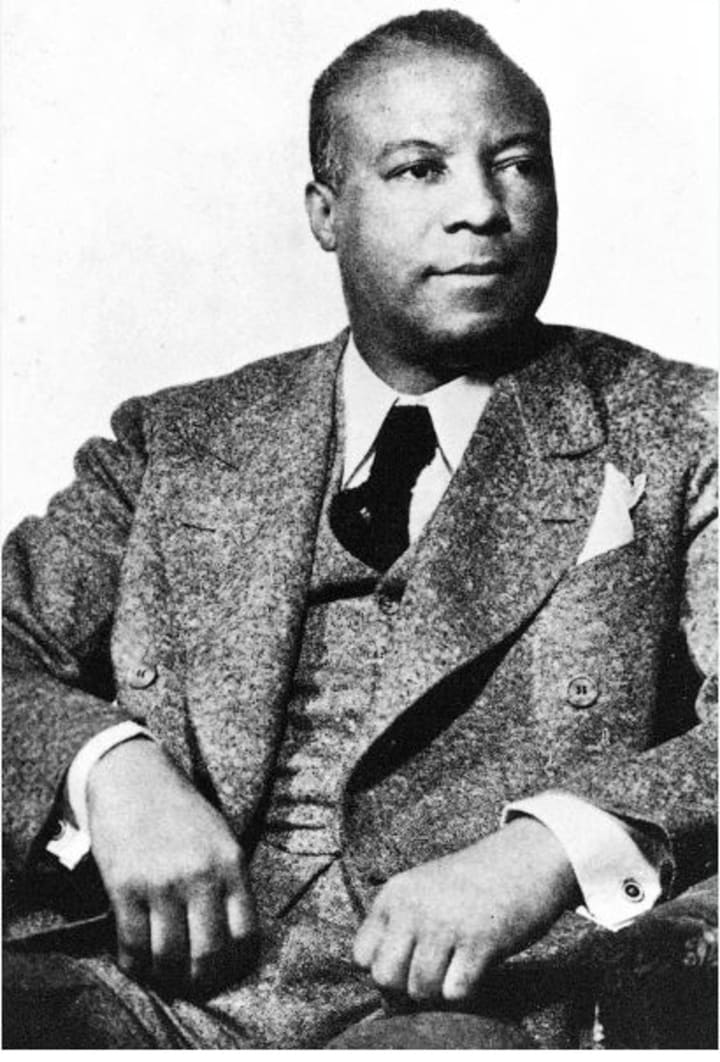

Under the leadership of A. Philip Randolph, Pullman porters formed the first all-black union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1925. By 1926, the association, (which boasted 31,000 members), persuaded the company to install small racks in each car, displaying a card with the given name of the porter on duty. Of the 12,000 porters and waiters then working for Pullman, only 362 turned out to truly be named George.

Randolph's organizing efforts helped end both racial discrimination in defense industries and segregation in the U.S. armed forces. He was also a principal organizer of the March on Washington in 1963, which paved the way for passage of the Civil Rights Act the following year.

Until the 1960s, Pullman porters were exclusively black, and have been widely credited with contributing to the development of the black middle class in America. It is literally on the foundation of their labor and determination that we have Labor Day at all, and that is truly worth honoring.

About the Creator

Veronica Coldiron

I'm a mild-mannered project accountant by day, a free-spirited writer, artist, singer/songwriter the rest of the time. Let's subscribe to each other! I'm excited to be in a community of writers and I'm looking forward to making friends!

Comments (2)

Oh wow, I never knew this origin story of Labour Day. Calling all the porters George was so terrible! And the real George did nothing about it 🤦♀️ So glad Randolph managed to put an end to it!

Thanks for sharing this bit of history, Veronica! A great read!