In the months leading up to the very first cheese-focused iteration of the Meilleur Ouvrier de France (MOF) competition, held every few years to recognise the country's the best craftspeople, Nathalie Quatrehomme remembers her cheesemonger mother, Marie, taking over the family living room, assembling and disassembling a plexiglass apparatus supporting dozens of different cheeses.

"It was 2000, and I was 17," Nathalie recalled. "She practiced building it on our living room table for a whole year."

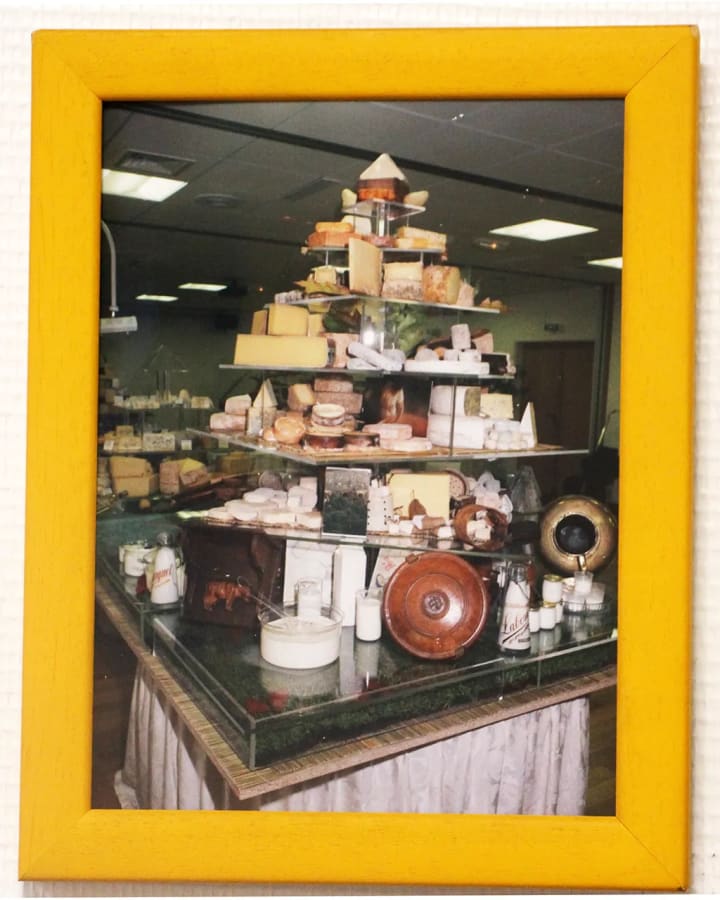

Marie's final project, a true work of art dubbed "La Pyramide des Saveurs" (pyramid of flavours), began, Nathalie recalled, with a base of real grass above which grew a veritable tower of cheeses that ranged in flavour and texture, progressing from mild to assertive, from milky and whey-weeping to dense and crumbly.

"She really started from the milk," Nathalie said. "The grass, then bottles of milk, then the cheeses, and up and up and up… it was really very pretty."

By the time Marie Quatrehomme was developing her tower of cheese, she had already undergone a litany of tests on cheese culture, technology and terroir for the competition. She had wowed jurors in blind tastings and fielded questions on French cheese appellations, which now number 46, each governed by a strict charter regulating everything from regional provenance down to animal breed. She was grilled on cheese legislation and interrogated on the economics of building a cheese buffet – all in the pursuit of recognition, not just from her peers, but from the French nation at large.

"You could say [La Pyramide] was the final trial," Nathalie said of her mother's work of cheese art. She recalled watching, once Marie had built it for the final time at the competition, as she was named one of the four inaugural champions of the category, alongside fellow cheesemongers Hervé Mons, Laurent Dubois and Christian Janier.

"That moment, I saw my father cry – my father, who never cries – so proud of his wife," Nathalie said.

The cheese world, like many culinary professions in France, has long been governed by gender. Nathalie explained that historically, at a fromagerie (cheese shop), a woman's place was often behind the counter, selling cheeses that were aged and otherwise cared for by her husband. (This is true of many traditional French food businesses – so much so that the word boulangère, much to the chagrin of female bakers, is still frequently defined in French dictionaries as being "the wife of the baker" and "she who sells the bread".)

In the realm of cheese, Marie's 2000 MOF win was ground-breaking. And she didn't just trailblaze in the brand-new cheese category; she was the first woman to earn any MOF distinction since the contest's founding more than 75 years earlier. (Marie's work even earned her, in 2014, the Légion d'Honneur, the highest French order of merit.)

"The first woman in any MOF category is incredibly significant, and here, we see that Marie Quatrehomme earned the title alongside several men," explained Lindsey Tramuta, journalist and author of The New Paris and The New Parisienne. "She was outnumbered but proved that gender had little to do with excellence in the métier (profession)."

Since 2000, a total of 24 cheese MOFs have been designated, representing producers like Dominique Bouchait, consultants and teachers like François Robin, and cheesemongers like all of the inaugural winners. Only four of these MOFs – Josiane Deal (2004), Laetitia Gaborit (2007), Christelle Lorho (2019) and Marie Quatrehomme – are women.

But breaking gender rules is far from the only thing that makes the Quatrehomme fromagerie stand out.

"I think you can't overlook the power of a compelling family story," said Tramuta. "Marie's father-in-law opened the business, she carried it to greatness, and now she's passed it on to her children who will hopefully ensure the heritage is preserved for generations to come. With that generational trajectory comes expertise, passion, dedication and a deep understanding of the market."

The flagship Quatrehomme shop stands on the border between Paris' 6th and 7th arrondissements. It was founded by Nathalie's grandparents in 1953: he, the son of a Loire Valley farmer who came to Paris in search of a new future, and she, the niece of a grocer from Brittany. That the shop, name and fromagerie tradition were legacies passed through Nathalie's father, Alain, renders Marie's choice to throw her hat into the MOF ring all the more audacious.

"My father was already quite established in the profession," explained Nathalie, citing his work for committees and the trade union. But there was more to it than that. "He's fairly proud and at the same time fairly discreet," she said. "So doing the contest wasn't really what he wanted, both out of pride and out of discretion."

Marie, on the other hand, "was a bit less well-known", Nathalie explained, but she was nothing if not dedicated.

"After 15 years in childhood education, she became a cheesemonger, wholly embracing her new craft by becoming both a respected authority on all things cheese related and an expert affineur (one who is trained in the art of aging cheese), all the while developing and cultivating close relationships with cheesemakers throughout France," explained Jennifer Greco, French cheese educator and tour guide based in Paris.

Despite their family legacy and star mother, a career in a fromagerie was not necessarily on the cards for the latest generation of Quatrehommes, Nathalie and her brother Maxime.

"There was never any pressure from them," Nathalie said of her parents. "It was a very demanding job."

Nathalie instead built a rewarding career in marketing, but after five years, in 2010, she took a chance and picked up a cheese wire once more.

"I said to myself. 'Try. Just try. Your parents, your grandparents worked their whole lives for this. It would be a shame not to try.'"

A decade later, what she'd told her parents would be a year-long experiment has become her full-time vocation.

"I love cheese. I love the product. I love to touch it. I love the smell of the cellar," she said. "I can swoon over a pressed cheese; I can fall in love with a denser, drier goat. I love blue – sometimes I get massive cravings for blue. I can positively relish a washed rind."

"I love cheese. I love the product. I love to touch it. I love the smell of the cellar."

It's no surprise, given the poetry that rises unbidden from her at the mere mention of her wares, that Nathalie has a certain talent for conveying her love of cheese to clients. It is indeed this task to which the natural extrovert is most often dedicated. She spends most of her time at the flagship shop, where an astounding variety of up to 200 cheeses may be on offer at any given time.

Today, she and Maxime run the family's five shops, which are dotted throughout Paris and the near suburbs. Like their parents and grandparents before them, they divide tasks according to age-old gender lines, albeit by circumstance rather than in adherence to these unspoken rules.

"I am indeed in the shop much more often," she said, noting that Maxime, meanwhile, has taken her father and grandfather's place behind the scenes.

"We didn't necessarily want to reproduce that schema," she said. "And of course, they were couples, and we're not, but there was that sort of thing of… my mom in the shop, and my dad in the back. It's funny."

She continued, "Honestly, more than my gender, it's really a question of personality."

The more reserved Maxime seems well-suited to the cellar, where he gives each cheese the treatment it needs to ripen to perfection. Some must be washed or rubbed with a brine or alcohol solution; others must be turned and brushed. Temperature and humidity must be closely monitored, and cheeses must be scrutinised so that they are only sold at the peak of perfection.

While some cheese producers age on-site, many others entrust the job – and their unfinished cheeses – to affineurs like Maxime at Quatrehomme. Acclaimed affineur Hervé Mons, who earned the MOF distinction in the same year as Marie, works with 130 producers to age 250 different cheeses at any given time at his facilities throughout the Roannais region in central France. At Quatrehomme, Nathalie explained, aging is done on a more modest scale.

"We age, but let's be honest, we're mainly aging small pieces," she explained. "We're in Paris; we're not aging our Comtés." (The 50kg pressed cheeses from the Jura department in eastern France would take up far too much of their limited Parisian real estate, as they are aged for months – or years – to reach their perfect doneness.)

Instead, Quatrehomme's 25 sq m cellar is devoted to more diminutive goat cheeses, sheep's milk tommes, bloomy-rinded Camemberts and Bries, and washed-rind Epoisses and Langres, which the siblings re-wash in alcohol as they age to runny, stinky perfection.

"We make lovely Maroilles washed in beer," she said. "And we do lovely Langres in Champagne."

And aging isn't the only way the siblings add a touch of personality to their cheeses.

"In addition to being agers, we transform cheeses."

"In addition to being agers, we transform cheeses," explained Nathalie, evoking a handful of offerings familiar to regulars of Parisian fromageries: Brie with truffle; Camembert dunked in Calvados and rolled in breadcrumbs. Others in the shop, however, are unique creations. Fourme d'Ambert is stuffed with a sweet fig and walnut paste to counterbalance the funk of the blue. A Camembert mendiant (beggar) is covered in jam, nuts, dried fruit and a touch of dark chocolate.

Maxime has even crafted two smoked goat cheeses, each boasting a burnt sienna colour. One is a tender, yielding crottin, the lactic acidity balancing the richness of the smoke. The other, a barrel-shaped Charolais from Burgundy, is infused with Japanese Nikka Whisky and has a fudgier, chalkier texture. Both creations required quite a bit of trial and error to develop.

"We had to balance when the cheese is aged enough – but not too much – to withstand the smoking process," Nathalie said. "Smoking induces heat, so if it's too hot, it'll melt the cheese."

Perceptibly just as knowledgeable about aging as her brother, Nathalie focuses on her front-of-the-house role at the shop, which for her, again, has little to do with being a woman.

"During my parents' era, there were only salesgirls," Nathalie said. "Now, our teams are much more mixed, with lots of men behind the counter."

And it's not the only way the cheese industry is evolving. Like many careers in the culinary realm, the role of fromager no longer bears the stigma it once did.

"As I child, I remember, having cheesemonger parents wasn't necessarily that well-regarded," she said. "It was better to have bankers for parents, or lawyers."

Now, the tides have turned, and the world of cheese is attracting people from other careers that would have once been held in higher esteem.

"Bankers are retraining to become cheesemongers," said Nathalie. "And that's great."

"Today, being a cheesemonger is a job that's linked to a passion and a history, with noble products made in beautiful regions by people who are really attached to a terroir."

"Today, being a cheesemonger is a job that's linked to a passion and a history, with noble products made in beautiful regions by people who are really attached to a terroir," said Nathalie. "I think people want to eat well, to know where their food comes from. And I think that all contributes to the fact that now we have an image of cooks and pastry chefs, but also butchers and fishmongers and cheesemongers, that has really evolved a lot."

Nathalie's passion for her work – and the legacy she has inherited – could make it seem as though she is primed to become the family's second MOF. (The seventh cheese-focused competition is taking place this October.)

But for the moment, Nathalie takes after her father in her humbleness, and she has yet to make a bid to follow completely in her mother's footsteps.

"Maybe that will be for another time in my life," she said. "For the moment, I'm still living my life as a young mother, trying to juggle work and life."

That said, the gleam returned to her eye as she smiled, shrugged and appended: "Never say never."

About the Creator

Mejra

Later, respectively, wander and suffer sorrow.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.