The Mysterious Sodder Children Disappearance

The strange occurrences in the early hours of Christmas Eve in 1945 that left their home in ashes and five children missing.

It was the winter night of Monday, December 24, 1945, in the rural town of Fayetteville, West Virginia. George and Jennie Sodder had just commenced minor Christmas Eve celebrations with their some nine children, an infant included, all of whom resided in the home together, with the exception of one absent son away serving in the military in World War II at the time. Five of these nine children asked their parents to stay up past their normal bedtime hour to play with their new Christmas toys, given to them by their older sister. Consenting to the idea, the Sodder parents went to bed, only to be woken at around 1 a.m. to their home ablaze.

In an unfortunate turn of events, only George, Jennie and four other children made their way out of the flaming residence with the two eldest boys sustaining singed hair as a result of their rushed evacuation. The other five children were thought to be trapped in the two upstairs bedrooms, so George made numerous attempts at entering, and found that a ladder typically leaning aside the building was dragged away from the two-story timber frame home to a nearby embankment. It wasn’t until 8 a.m. when the local Fayetteville Fire Department arrived on scene to find a pile of smoking ash and five missing Sodder children.

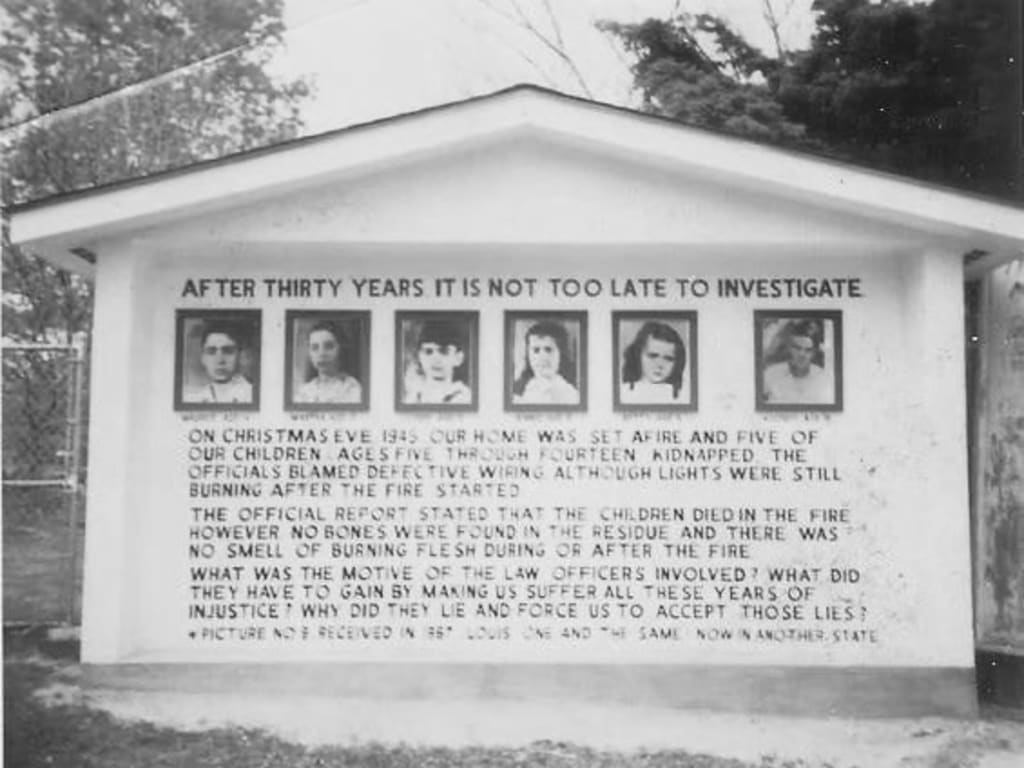

With a lack of evidence, investigators deemed the case a fire caused by faulty wiring, something George argued to be inaccurate the remainder of his life until his death in 1968. For decades, the Sodder family did not believe their five children perished in the fire, rather that some form of foul play took place, and a billboard featuring their lost children’s photographs was placed along Route 16. Other than a photograph of an adult male that was mailed to the Sodder family by an unknown sender that they believed may be their son all grown up, they never saw any traces of their children again.

Christmas Eve, 1945

The early morning disappearance of the five Sodder children involved more than a home fire and moved ladder; Jennie noted to authorities that at roughly 12:30 a.m., she received a phone call from a woman who asked for an individual who’s name Jennie did not recognize. She respectfully told them they had the wrong number and the woman on the other end laughed and hung up. Thinking little of this other than its mildly odd, prank-like nature, Jennie went back to sleep. In an article posted on the Smithsonian website, where author Karen Abbott conducted an interview with Sodders’ granddaughter, prior to quietly going back to her bedroom, Jennie noticed that the front door was not locked, all of the downstairs lights were on and all curtains were opened. Only one daughter was asleep on the sofa, so she assumed all other children were in their respective bedrooms, locked the door, turned off all lights and closed all curtains before making way back to bed herself.

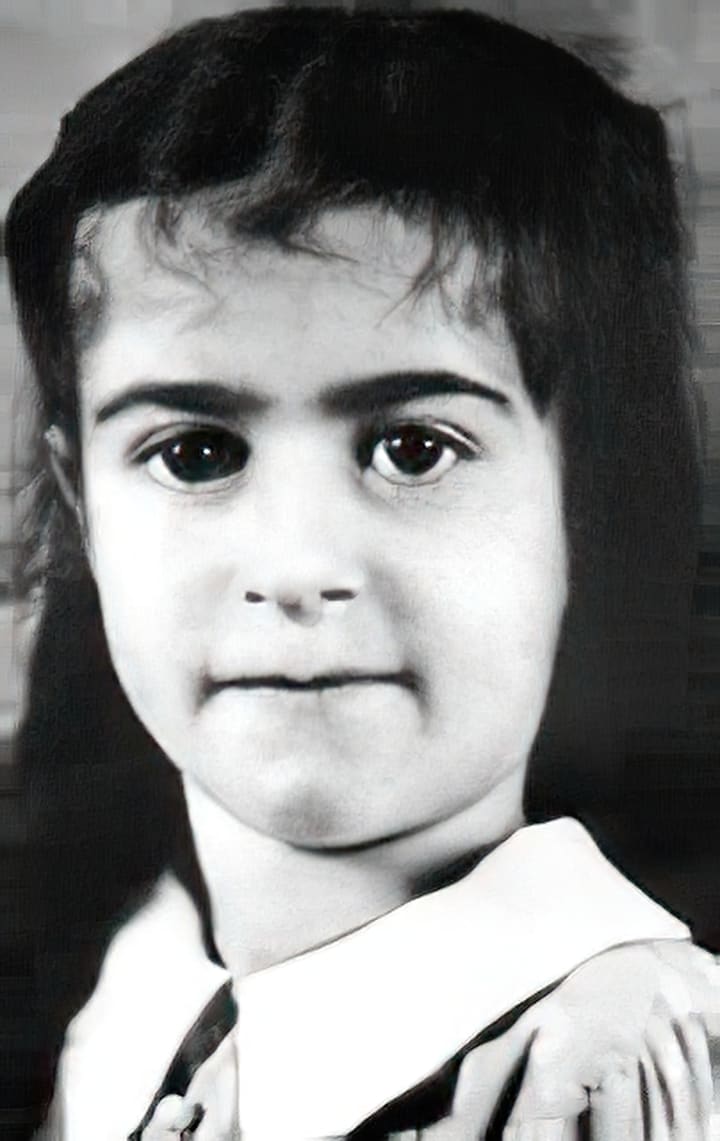

Jennie’s attempt to rest was interrupted by a loud thud atop the roof, followed by what the article refers to as a “rolling noise”. Finally, smoke creeping into their bedroom woke Jennie and George. Realizing their home office was in fact on fire, both called for all children to get out. Sylvia, 2, Marion, 17, George Jr., 16 and John, 23, were the four children that escaped the burning inferno, but their younger siblings, Betty, 5, Maurice, 14, Louis, 9, Jennie, 8, and Martha, 12, were thought to be trapped inside.

George immediately attempted to re-enter the home by breaking a window, slicing his arm, only to find their entire downstairs level up in flames. He searched for a ladder that he typically left propped up against the house, planning to use it to climb through an upstairs window to gather his children, but it was not in its usual place on the property. In an effort to reach his children once again, George hoped to move one of two coal trucks that he used for work up to the window to climb onto and into a second-story window, but failed to get either vehicle to start. As the use of any water was a bust beings it was frozen inside of a nearby rain barrel, the Sodders were unable to put out the fire that quickly reduced their home to ashes in a matter of allegedly just 45 minutes.

While George scrambled to gain access to the burning building, Marion sprinted to a nearby neighbor’s house to phone the fire department. After many attempts on her part, as well as another neighbor that noticed the blaze, to contact first responders, they were unable to get an operator response. The Fayette Fire Department was some two and a half miles away from the Sodder family property that was in the country north of Fayetteville, so that same neighbor traveled into town to find the fire chief, F.J. Morris, who then initiated a call tree system where one fire fighter was to call another, then that fire fighter was to call another member, and so on. Several hours later when the fleet arrived at 8 a.m., the flames had ceased long before and all that was left was four children and two parents assuming their other five children were dead.

The Findings

On Christmas Day, after a short search through the ashes, no human remains were found, and chief Morris noted that the fire was hot enough to cremate the bodies. The cause of the fire was deemed “faulty wiring” by a state police inspector who sifted through the scene. Five death certificates were issued with the cause reading “fire or suffocation” and the Sodder family decided to erect a memorial where their home once stood for their lost children. Pouring five feet of dirt above the basement, the family planted a garden on the surface, yet they could not escape the suspicion that their children were still alive and were instead kidnapped.

A local minister gave a tip to George that chief Morris found what he had believed to be a human heart at the fire site, though, he failed to release this information to the Sodder family, placed it in a dynamite box, and buried it in the dirt below the charred rubble. C.C. Tinsley, a private investigator, was hired by the Sodders and he convinced the fire chief to guide them to the location on the premises where this said burial took place. The piece of potential evidence was sent to an area funeral director, where an analysis of the organ concluded it to be beef liver, free of any fire exposure. As time went on, rumors began circulating that chief Morris planted the beef liver at the site where the Sodder home burnt down in hopes that it would assist the family in moving forward with their grievances and therefore cease the investigation. Incidentally, on a visit to the Sodder children memorial, youngest daughter, Sylvia, found a firm piece of rubber; George identified the object as a napalm, which they believed to have been the noise that Jennie heard the night of the inferno.

Far from believing that their children were no longer amongst them, the Sodders concluded yet another sweep of the fire site in August of 1949, this time bringing in a Washington, D.C. based pathologist by the name of Oscar B. Hunter. The search was in-depth and thorough, much different than those conducted prior, and the findings consisted of four shards of vertebrae. Accordingly, Hunter sent them to the Smithsonian Institute, whose report deemed the bones to be the lumbar vertebrae pieces of a human aged 16 to 22 at the time of death. It is important to note that the eldest Sodder child to go missing was 14 at the time of his disappearance or death, though, the report stated: “Since the transverse recesses are fused, the age of this individual at death should have been 16 or 17 years. The top limit of age should be about 22 since the centra, which normally fuse at 23, are still unfused. On this basis, the bones show greater skeletal maturation than one would expect for a 14-year-old boy (the oldest missing Sodder child). It is however possible, although not probable, for a boy 14 ½ years old to show 16-17 maturation.” The Smithsonian report concurred that the lone four vertebrae bones that were discovered at the site arrived there via the dirt George used to construct the memorial for his children, as there were no signs of exposure to fire yet again and it was unlikely to find such small traces of human remains when five persons were said to have perished.

The Sightings

The strange case surrounding the disappearance of the Sodder children captured the attention of thousands as word spread, and this prompted several individuals to come forward with their sightings following the fire. These compiled of reports to have seen the children at a tourist shop west of Fayetteville the morning after the blaze, seeing them inside of a car within close proximity to the Sodder home while it was burning, and their supposed appearance at a hotel in Charleston one week following Christmas Eve. The hotel encounter was brought forth by a woman once she recognized the children she had seen to match the faces printed in a newspaper. She recalled them to have been accompanied by two women and two men, both speaking Italian, and when she spoke friendly to the children, one of the men broke off the interactions and the group gave the woman the cold shoulder the remainder of their transactions. However, none of these leads amounted to anything with regards to the investigation.

Subsequent to the vertebrae study at the Smithsonian Institute, the Capitol in Charleston held two hearings where Governor Okey L. Patterson and State Police Superintendent W.E. Butchers announced the “helpless” Sodder case to be closed. In reply to this, George and Jennie positioned the famous Sodder children billboard along Route 16 with all five of their children’s photographs side by side. The billboard listed a brief summary of the fateful Christmas Eve night, as well as the children’s names, descriptive features and their age at the time of the disappearance. Where it stood for some four decades, the billboard was a somber, yet historic symbol to long-time locals, knowledgeable lookie-loo’s, and any unaware passerby. The Sodders noted on the roadside advertisement a $5,000 reward for the finding of their children, a number which they later increased to $10,000.

More reports started to flow in, likely as a result of the billboard, from individuals far and wide claiming to know the location of some of the Sodder children. A woman claimed that Martha was in a convent in St. Louis, a Texas resident thought to have overheard an incriminating conversation regarding a West Virginia fire on Christmas Eve night, and another tip came from Florida saying that the children were there residing with a distant relative to Jennie. With each lead that came, George followed, traveling all around the country, only to return home each time with no prevail.

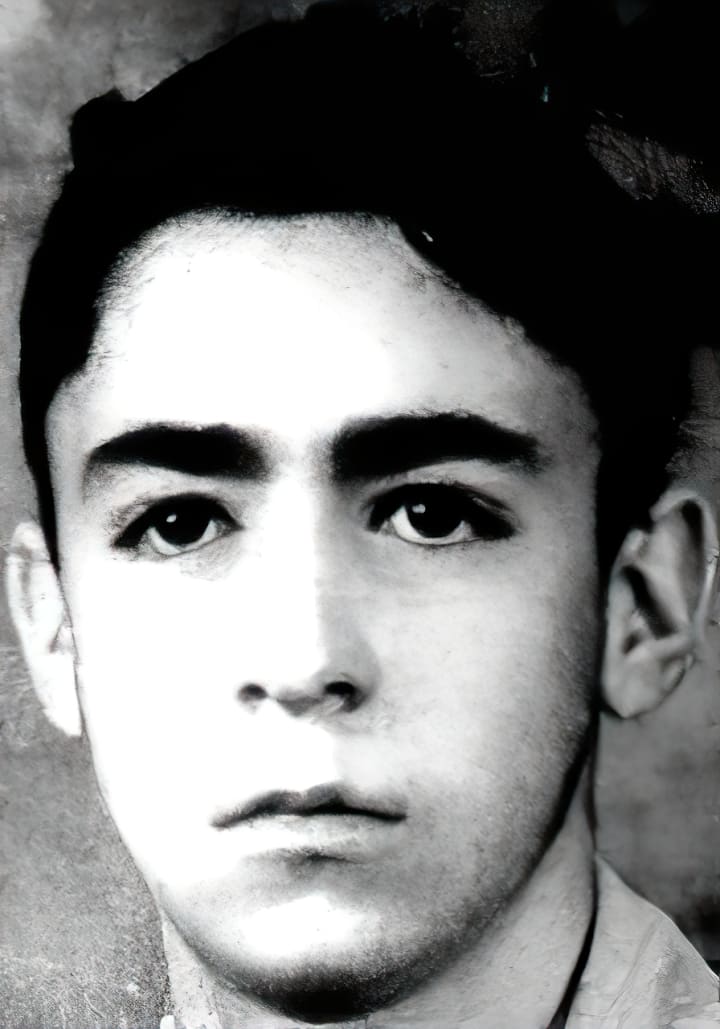

Some 20 years following the placement of the Sodder children billboard, a letter was received in the mail that was unaddressed by the sender, but postage stamps indicated it arrived from Kentucky. Inside, Jennie found a photograph of a young man, with a handwritten note on the back that read, “Louis Sodder. I love brother Frankie. Ilil Boys. A09132 or 35.” The Sodders believed the man in the photo resembled their Louis who disappeared during the fire. They hired a private investigator once more, only to never hear from him again after having sent him to Kentucky for detective work. Having no other options and fearing of putting their children’s lives in danger, George and Jennie had the photograph added to the billboard. After George’s passing in 1968, Jennie surrounded her home with a fence, and the Route 16 billboard remained in place until 1989 after her passing.

This Christmas Eve, it will be 75 years since the fire broke out at the Sodder family’s rural, West Virginia home. The convoluted case is still discussed to this day, and the five children originally thought to have been trapped inside the burning structure were believed by their parents to have been alive elsewhere. George and Jennie spent the remainder of their lives searching for leads, clues and answers, but were never to receive any that lead to the findings of Martha, Louis, Betty, Maurice or Jennie. Many feel that the handling of this case by the Fayetteville Fire Department sounds like a cover up, and this coincides with the idea that the children were stolen by the Italian mob, as George immigrated from Italy, but never spoke of his reason to have left. Whatever one is to make of this mystery, it is an early-American cold case to remember.

Sources:

Abbott, Karen. “The Children Who Went Up In Smoke” Smithsonian Magazine, December 25, 2012; “Betty Dotty Sodder” The Charley Project, July 4, 2015.

Enjoyed this article? Share it below on your Twitter or Facebook to help others find me! Follow me on Pinterest @free@freelancer and Medium @free2freelance (I'll follow you back)!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.