A Neuroscientist discovered he was a Psychopath

When researching brain scans for characteristics associated with psychopathic conduct, James Fallon discovered that his own brain suited the criteria.

James Fallon has always been fascinated by the criminal mind. The neurologist at the University of California-Irvine has been studying psychopaths' brains for over 20 years. He investigates the scientific foundation of conduct, and one of his specializations is attempting to determine how a murderer's brain varies from yours and mine.

Fallon made an astonishing discovery around four years ago. That happened during a talk with his then-88-year-old mother, Jenny, during a family cookout.

"I suggested to Jim, 'Why don't you look into your father's relatives?'" Jenny Fallon reflects. "I believe there were cuckoos back there."

Fallon looked into it.

"There's a whole bloodline of incredibly aggressive individuals — murders," he claims.

Thomas Cornell, one of his direct great-grandfathers, was hung in 1667 for killing his mother. Seven additional accused killers descended from the Cornell family, including Lizzy Borden. Fallon jokingly refers to her as "Cousin Lizzy," who was accused (and controversially acquitted) of murdering her father and stepmother with an ax in Fall River, Massachusetts, in 1882.

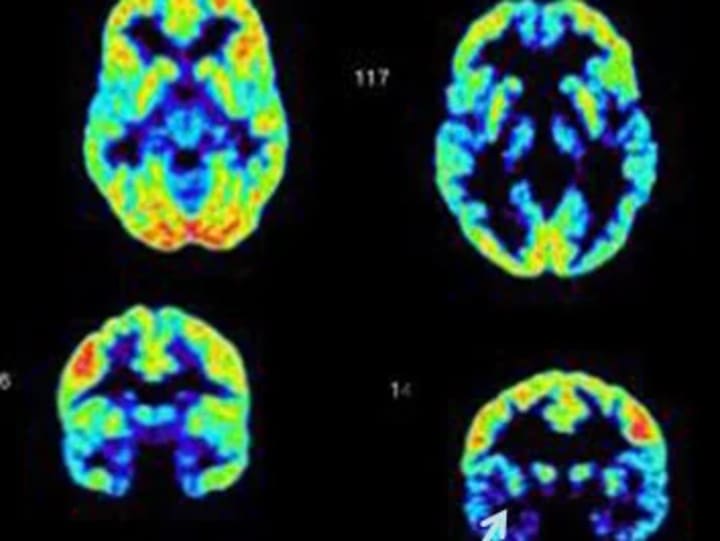

Fearful of his ancestors, Fallon set out to determine if anyone in his family possessed the mind of a serial murderer. He knew exactly what to look for since he had examined the brains of dozens of psychopaths. To explain, he opened his laptop and displayed a picture of a brain on the screen.

"This is not a normal brain," he explains. There are yellow and red spots. Next he gestures to another area of the brain, this time at the front, right behind the eyes.

"Look at that — virtually nothing here," Fallon remarks.

This is the orbital cortex, which Fallon and other researchers believe is responsible for ethical conduct, moral decision-making, and impulse control.

"Those who have poor activity [in the orbital cortex] are either free-spirited or sociopaths," he explains.

The Scans of Fallon

Fallon claims that the orbital cortex acts as a brake on another area of the brain called the amygdala, which is involved in anger and hunger. Yet, in certain cases, there is an imbalance; the orbital cortex isn't doing its function, maybe as a result of a brain damage or because the person was born that way.

"What remains? What takes control? "He inquires. "The part of the brain that is responsible for your id-type activities, such as fury, aggression, hunger, sex, and drinking."

Fallon claims that no one in his family has any significant issues with those actions. But he wanted to be certain. He had everything he needed: he had previously convinced ten of his close relatives to participate in a PET brain scan and blood sample as part of a research to determine whether his family was at risk of acquiring Alzheimer's disease.

He reviewed the photos and compared them to the brains of psychopaths after learning about his violent family history. His wife's scan came back normal. His mother is typical. His siblings are typical. His children are typical.

"And I looked at my own PET scan and found something unpleasant that I didn't discuss," he adds.

What he didn't want to show was that his orbital cortex seemed to be dormant.

"Looking at the PET scan, I appear just like one of those killers."

Fallon warns that this is a developing field. Scientists are only now beginning to investigate this part of the brain, much alone criminals' brains. Yet, he claims that evidence is mounting that some people's brains predisposition them to violence and that psychopathic characteristics may be handed down from generation to generation.

The Three Ingredients

That takes us to the next stage of Jim Fallon's family experiment. In addition to brain scans, Fallon examined each family member's DNA for genes linked to aggression. He examined 12 genes linked to aggressiveness and violence and honed down on the MAO-A gene (monoamine oxidase A). This gene, which has been the subject of much investigation, is also known as the "warrior gene" because it modulates serotonin in the brain. Several experts believe that if you have a certain variant of the warrior gene, your brain will not respond to the soothing benefits of serotonin.

Fallon selects another slide from his computer. It provides a list of family members' names with the genotyping results next to them. Except for one guy, everyone in his family carries the low-aggression version of the MAO-A gene.

"Do you see what I mean? I am completely confident. I have the pattern, the dangerous pattern, "he adds, pausing. "In some ways, I'm a natural murderer."

Fallon is being ironic — sort of. He does not think that genes influence his or anybody else's fate. They just point you in one direction or the other.

"When I put the two together, it was frankly a bit scary," Fallon laughs. "You begin to examine yourself and think, 'I could be a psychopath.' I don't believe I am, but this appears to be [the brains of] psychopaths and sociopaths that I have seen before."

Diane, his wife, was asked what she thought of the outcome.

"I wasn't very concerned," she laughs. "I mean, I've known him since I was twelve years old."

According to specialists who research this subject, Diane probably does not need to be concerned. They feel that brain patterns and genetic make-up are insufficient to turn someone into a psychopath. A third component is required: childhood abuse or violence.

"And, thankfully, he wasn't mistreated as a child," Diane continues, "so I've lived to a ripe old age so far."

The 'Neurolaw' Revolution

Jim Fallon believes he had a wonderful upbringing, being spoiled by his parents and having love ties with his siblings and extended family. Crucially, he claims that this voyage through his mind has altered his perspective on nature and nurture. He used to believe that our DNA and brain function determined everything about us. Yet now he believes his upbringing made all the difference.

"We'll never know, but the way these patterns are appearing in the broader population, if I had been mistreated, we may not be sitting here today," he adds.

Fallon has compassion for the psychopaths he examines, describing them as having "a poor roll of the dice."

"It's an unfortunate day when all three of these things come together in a horrible way," he explains.

But what about those who rape and murder? Should we sympathize with them? Should they be able to claim in court that their minds forced them to do it? Welcome to the emerging realm of "neurolaw," in which neuroscience is utilized as evidence in court.

About the Creator

Victoria Velkova

With a passion for words and a love of storytelling.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.