William Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale

By Doc Sherwood

Written sometime between 1609 and 1611, The Winter’s Tale is grouped alongside Cymbeline, Pericles and The Tempest as Shakespeare’s four Late Comedies, also known as his Romances. These are often regarded as Shakespeare’s final plays, or at any rate the last ones he wrote alone, since his remaining works after The Tempest were all co-authored with John Fletcher. (Strictly speaking, Pericles was co-authored too.) Like The Tempest and Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale did not see print during Shakespeare’s lifetime. The earliest text is in the First Folio of 1623.

The four Romances, composed by Shakespeare late in life, look back to the beginning of his career. In the 1590s, a group of writers known as the “university wits” had made such stories very popular. The Old Wives’ Tale (c. 1590) by George Peele was their model. Jonathan Bate comments that a romance of this kind is “like a fairy story: it is not supposed to be realistic and it is bound to have a happy ending. Along the way there will be magic, dreams, coincidences, children lost and found.” Cedric Watts agrees that traditional romances “offer the far-fetched, strange, peculiar and exotic; often they invoke the supernatural.”

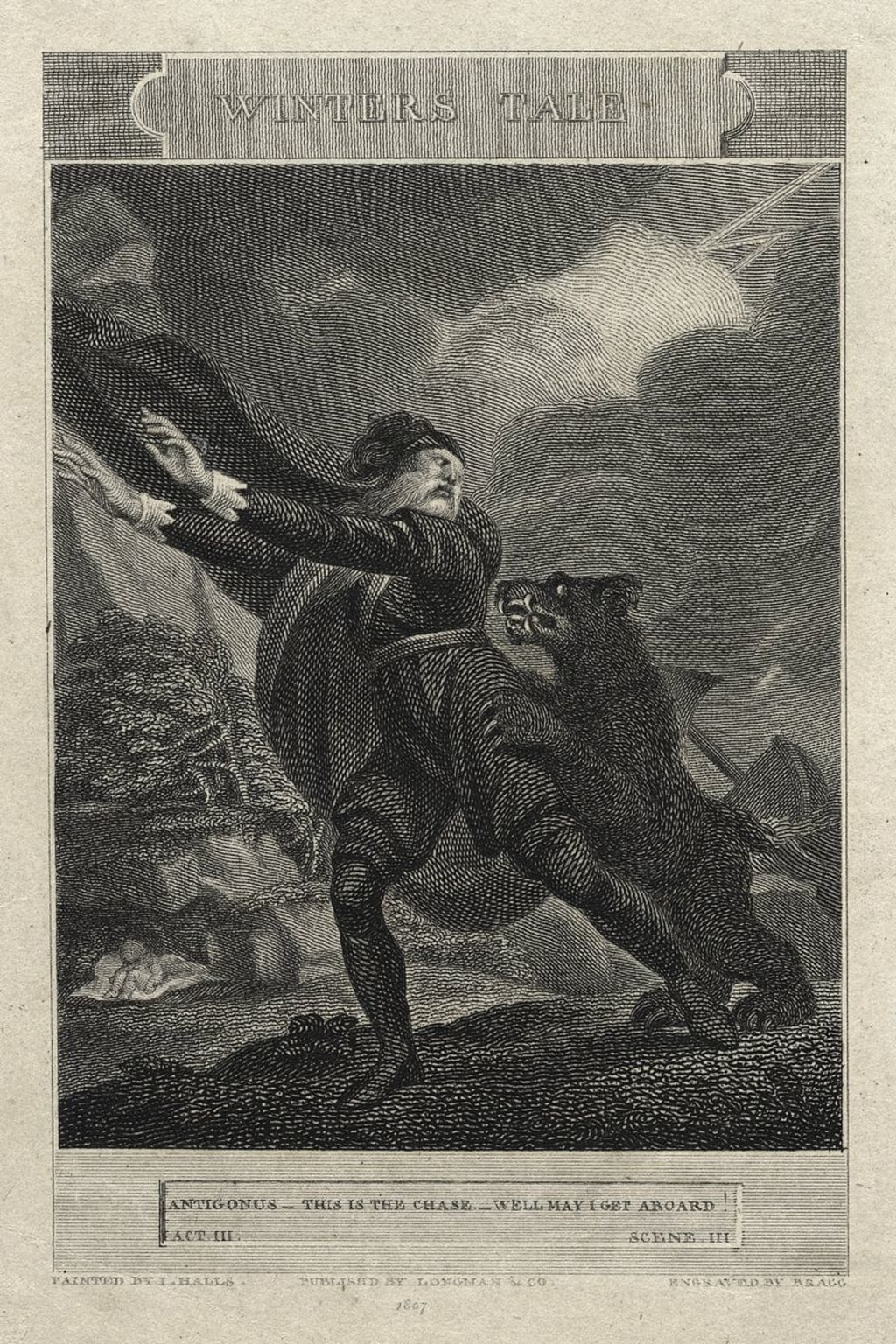

Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale was based on another romance from this period, Pandosto; or, The Triumph of Time, by Robert Greene of all people. There was no love lost between Shakespeare and Greene, and in fact the earliest published document referring to William Shakespeare that has ever been discovered is an insulting attack on him written by Greene! In addition, The Winter’s Tale contains a famous sequence involving a bear for which Shakespeare drew direct inspiration from Mucedorus, another old chivalric romance which was enjoying a revival in the 1610s.

It’s not known for certain why Shakespeare, after having produced what later generations would call his “four great tragedies,” turned at the end of his career to these earlier authors and a style of writing that had been fashionable decades ago. Bate however suggests that “a gentler mode of tragi-comedy and pastoral romance, with a distinctly royalist agenda, suited the times.” One major difference between the political climate of England at the start of Shakespeare’s career and at its end was that Queen Elizabeth the First was childless, whereas King James had a very large royal family. Plays in which princes and princesses married were therefore topical in the early Jacobean era.

Although The Winter’s Tale is not one of the three works by Shakespeare originally identified by F. S. Boas as his “Problem Plays,” that title has frequently been applied to it since. This has much to do with the ending, which, like those of two of Boas’s selection (Measure for Measure and All’s Well That Ends Well) resembles that of a traditional comedy but fails to completely satisfy.

Paulina and Hermione’s decision to fake the latter’s death, and for Paulina to keep her in seclusion throughout the subsequent sixteen years, is perhaps fair enough considering Leontes’s treatment of her thus far. However, for Paulina to continue punishing the King, all the while knowing Hermione is actually still alive, can feel excessively cruel. Indeed, since Leontes is the man who sent her first husband to his death, Paulina’s actions might appear more like revenge than justice.

Equally troubling, however, is the formal apology Leontes offers Hermione and Polixenes for his earlier mistrust – mistrust which was directly responsible for the deaths of Antigonus and Mamillius. Hermione may have turned out to be alive after all, and Paulina may have a new husband in Camillo, but a man and a boy are still dead. It’s tempting therefore to say Leontes’s apology is far from sufficient.

A footnote on Antigonus is that Charles and Mary Lamb, in their 1807 retelling of Shakespeare’s comedies and tragedies Tales From Shakespeare, treat that same character with notable unfairness. His fatal mauling by the bear is described by the Lambs as “a just punishment on him for obeying the wicked orders of Leontes.” In Shakespeare’s original play, however, Antigonus persuades Leontes to abandon Perdita when the King is determined to kill her in her cradle there and then. Antigonus in fact saves the baby’s life, by arguing for a course of action in which she will – and, as it turns out, does – stand a chance of survival.

Charles and Mary Lamb didn’t misread or misunderstand Shakespeare. The changes they make to Antigonus’s part in The Winter’s Tale are deliberate, to serve the purposes of poetic justice. In a children’s story written to Nineteenth-Century moral standards, it’s much easier if someone torn apart by a bear is a villain who deserves such a fate, not a kindly man who was doing the best he could do in a difficult situation. F. S. Boas himself coined the term “problem plays” in 1896, and it may be argued that the three centuries of ethical redefinition between that time and Shakespeare’s were the reason some of the plays were problems to Boas in the first place.

At The Winter’s Tale’s approximate midway-point Shakespeare brings Time himself onto the stage, probably in the traditional personified form of Old Father Time. This character explains to the audience that sixteen years have passed, Perdita has grown up into a beautiful girl who still believes she is only a shepherd’s daughter and has no idea she is really a princess, while King Polixenes’s son Florizel (who was mentioned in the first half of the play but not seen) has likewise grown into a handsome young man. It will come as no surprise to learn this pair meet and fall in love, or that their eventual marriage supplies the happy ending to the play.

Shakespeare’s friend Ben Jonson was scornful about the device of using Time as a narrator, but this didn’t stop Shakespeare doing something similar in Pericles. In addition his other two late comedies, though they do not jump from past to present in quite this manner, both involve a previous time of unrest when the heroes and heroines were young. Cedric Watts writes:

“Such a time-gap permits innocent children, representing new hope for the future, to become old enough to fall in love, marry and procreate. Their loving harmony compensates for the hateful discords of the past; and their virtue can be dynamic, continuing into the future and perhaps in their offspring.”

Some conclusions have been made many times before. Nevertheless, here we might remember William Shakespeare himself lost his only son to illness at the age of eleven. Watts perhaps is close to answering one of our earlier questions as to just what it was that drew Shakespeare to this kind of narrative, late in life, by which time his own winter’s tale was well-advanced towards curtain-call.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (4)

Lol, the only Hermione that I know is from Harry Potter. I'm so sorry, I'm just not very well versed with literature but I enjoyed reading this!

Dear Doc - You inspire me to "Crack a Book" other than from my 'James Patteson' in home library; read every one of them. I know that you do stage productions and I would just love to see 'Clips' of a performance. Jay

Shakespeare was very good at writing drama , would make star magazine weep. Shakespeare writing are like riddles to me until I read a book the interpretation in plain English. He is certainly a deep thinker . Great explanation conclusion on the life of Shakespeare 🥰 I would love to be your student. I love how you simplify and share informations on authors that takes deep research .

I have never been able to enjoy The Winter's Tale, probably because I read it at a time when my knowledge of English was still poor. And the version I saw in my local theatre was not very good. A few of the actors struggled. I wish I had had access to this essay at the time, it would have certainly helped me understand the play better. I'll probably try to read it again in the near future. As always, thank you for an excellent post!