The American Civil War: A Literary Perspective

By Doc Sherwood

In 1861, an America irretrievably divided over the issue of slavery descended into Civil War. Eleven southern States, determined to protect their right to keep slaves, seceded from the Union. Styling themselves the Confederate States of America, these entered into open hostilities with the north.

As with many other instances from American history, works of literature played a significant part in determining the course of this conflict. 1839 had seen the publication of Angelina Grimké Weld’s American Slavery as It Is, which was the inspiration for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s landmark novel on the evils of slavery, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Abraham Lincoln, fourteenth President of the United States and remembered as The Great Emancipator who won the Civil War and set the slaves free, said of Stowe that he would like to shake the hand of “the little woman who started a great war.”

Lincoln was one of many who recognized a direct link between literary works and the course of American history. A comparable example is Mark Twain’s half-serious assertion that Sir Walter Scott’s romanticized depiction of medievalism, along with the ready availability of his books in the United States, caused the Civil War by informing Southern notions of a functional master-and-slave society.

The south was not slow in mustering a literary response to the north. Mary Eastman’s Aunt Phillis’s Cabin, published the same year as Uncle Tom, was a direct rejoinder to Stowe’s novel and argued that southern slaves were in fact happy the way things were. Despite its dubious claims, Eastman’s tract spawned a string of imitators, while other southerners took a more hands-on approach to matters literary. In 1835, literature of the anti-slavery Abolitionist movement was publicly burned in Charleston, and in 1837 an Abolitionist editor was murdered in Illinois. Meanwhile, Josiah Nott and George Fitzhugh published supposedly scientific studies in defence of slavery and the southern cause.

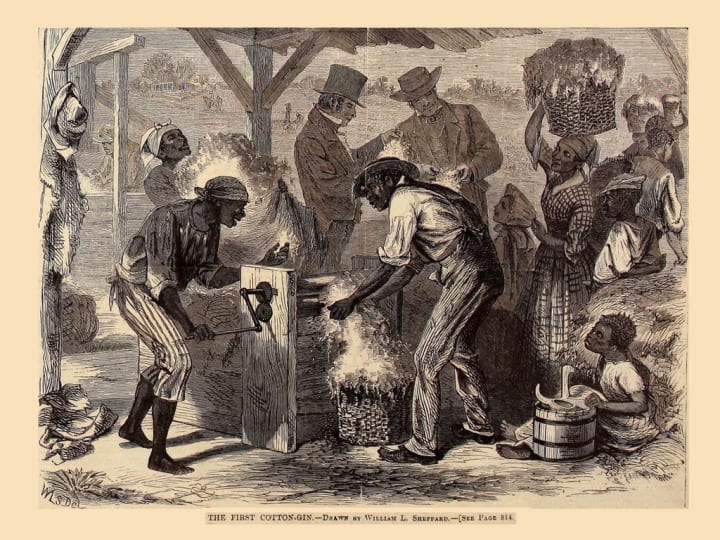

Practical economic realities, unfortunately, carried more weight than these flimsy academic and literary standpoints. In 1860, nearly sixty percent of American exports by value was in the form of southern cotton, a product of slave labour. The invention in 1793 of Eli Whitney’s cotton gin had revolutionized farming techniques and vastly increased the crop’s profitability. Most southern landowners argued that slavery was a necessity on which the nation’s fortune depended, which led in turn to northern resistance to Abolition from textile mill owners who were dependent on southern cotton, and urban workers who feared that an influx of freed slaves would result in job competition.

Slaves themselves contributed to the literary United States even before the war, through folktale, song and the distinctively American autobiographical form called the slave narrative – that is, the life-stories of freed or escaped slaves. This last became especially significant after 1850, when the Fugitive Slave Act of that year granted federal marshals the power to ship escaped slaves back to their owners without trial. The Transcendentalist author Henry David Thoreau was among the northerners who risked their own freedom by defying this harsh law, and helping runaway slaves on their flight to Canada.

Transcendentalism, with its belief in the divine soul of every human being, was opposed to the practice of slavery. Thoreau and his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson were devoted Abolitionists, and their writing played a part in encouraging others to join the struggle. Most Americans who resisted slavery, however, were of a like mind to these Transcendentalists.

In 1776 the Declaration of Independence had promised full equality, but the subsequent US Constitution had allowed slavery to continue. Thomas Jefferson, principal author of the Declaration, was himself a slave-owner – although, paradoxically, he also spoke out against slavery. Such contradictions as these were fast becoming impossible to condone.

With tensions between north and south ever mounting, outbreaks of violence began to occur. Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner led rebellions in 1822 and 1831 respectively, which were suppressed by southern authorities. John Brown was a northern abolitionist who believed in extremist tactics, including guerilla warfare and civilian massacre. His raid on Harpers Ferry in October 1859, for which he was arrested and hanged, is considered by some the beginning of the Civil War. It was Henry David Thoreau’s championing of Brown through his writing that made him a hero and martyr for the northern cause.

The first southern State to exit the Union was South Carolina, who in December 1860 declared their relationship with the United States of America henceforth “dissolved.” That same proclamation was clear enough on the cause: the election of President Lincoln, “whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.” As Paul S. Boyer points out, from this we may see that slavery was from the first the issue at stake, despite the contrary claims of later southern apologists.

On April the Twelfth the following year, with the Confederacy by now eleven states strong, pitched battle finally broke out at Fort Sumter in Carolina. The American Civil War had begun.

Lincoln was a lawyer by profession, and came of a humble background. He first called the nation’s attention in 1858 while running for Senator. Part of his campaign was a spirited attack on the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of the previous year, which had ruled against the rights of slaves to take legal action.

It’s true that three of the northern States to remain under Lincoln’s command in the Civil War still permitted slavery, and that preserving the Union should therefore be regarded as his prime objective. Lincoln however was strongly opposed to slavery, and through his influence Abolition soon became a driving force for the Union army.

Many Confederates hoped Britain would support them in their struggle against the Union, partly because the British textile industry relied on American cotton, and also because the United States was an old enemy. Besides the Revolutionary War, a subsequent skirmish between the powers had occurred in 1812. Lincoln, aware of this, warned the British government on the outbreak of hostilities not to meddle in what he described as an American internal affair. Britain however had abolished its own slave trade in 1833, and never recognized the Confederacy. Nor, indeed, did any other nation.

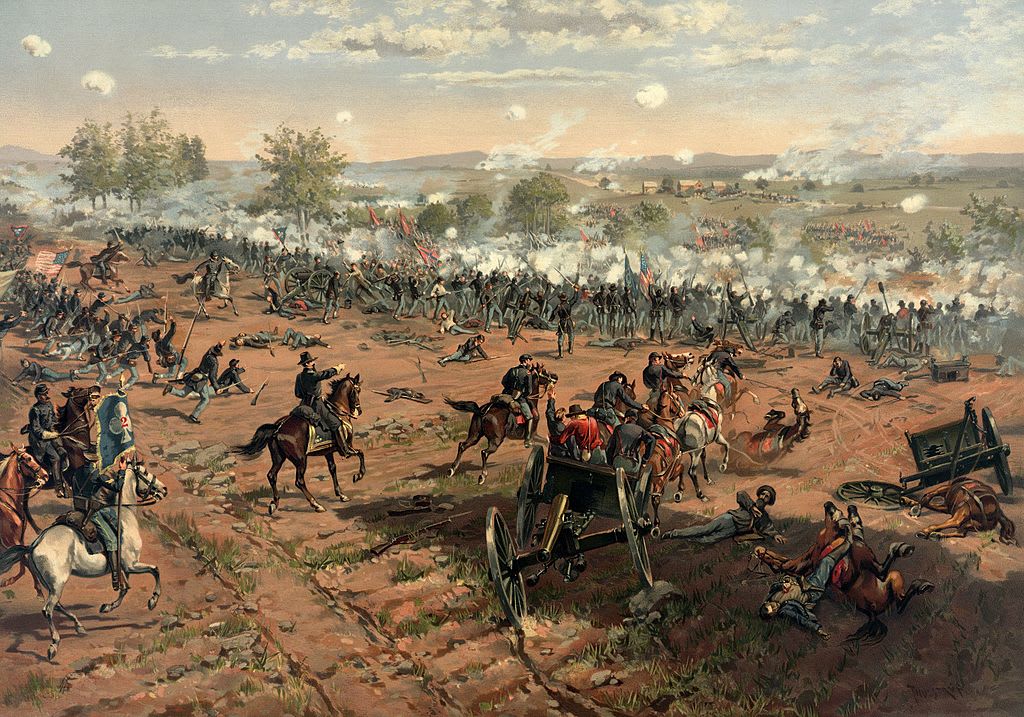

After a string of Confederate victories in Virginia and Maryland, while Union ground was recovered in Tennessee and Mississippi, the two armies met at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in July 1863. The town itself was strategically unimportant, and Confederates were in fact marching on Washington D.C. to demand the north’s surrender. However, after three days of intense fighting the south’s advance was halted. The Civil War’s turning-point had been reached.

Lincoln paid a visit of state to Gettysburg later the same year, to dedicate a cemetery for the fallen troops, and there delivered what Paul S. Boyer ranks “among the greatest of all Presidential speeches.” The Gettysburg Address, just 272 words long, acknowledges the crisis threatening those principles on which the United States of America had been founded, whilst also declaring those principles are worth fighting for. Lincoln’s vow that democratic government “shall not perish from the Earth” has helped consolidate his reputation as one of America’s single most heroic men.

In September 1862, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation which guaranteed freedom to all slaves in Confederate territories seized by the Union. Freedmen were welcomed into the northern army, and by the end of the Civil War more than 186,000 former slaves had served as soldiers. This swelling of the Union ranks was a factor in their eventual triumph. March 1864 saw the invasion of Virginia by future President General Ulysses S. Grant, whilst General William T. Sherman orchestrated a devastating assault on Atlanta.

On April the Ninth 1865 at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, Confederate leader General Robert E. Lee surrendered. The American Civil War was over.

Nine days after the end of the war, Lincoln was shot dead by a Confederate sympathizer named John Wilkes Booth. This tragic postscript to the American Civil War also carries a strange relationship to the literary world.

Booth was a Shakespearean actor by profession, the older brother of Edwin Booth who is regarded as the greatest of all American Shakespeareans. Their father, Junius Brutus Booth, was also an actor and was named after the Roman general remembered by history as Julius Caesar’s murderer. Shakespeare, of course, wrote a play about Caesar, and the men of the Booth family had staged a production of it in 1864.

It is known that John Wilkes Booth had come to model himself on the figure of Brutus. When he shot Lincoln, he shouted out: “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” which in Latin means “thus always to tyrants.” Tradition has it that Brutus spoke those words to Caesar on striking the killing blow. “Sic Semper Tyrannis” was also the motto of the southern State of Virginia.

We may never know whether Booth truly believed himself the next Brutus, striving to save another republic from the next potential Caesar, but the literary and historical overlap is disturbing. If Sir Walter Scott can be accused of starting the Civil War, then can the Lincoln assassination likewise be blamed on Shakespeare?

The work begun by the Abolitionist movement and Lincoln was completed after the latter’s death. Slavery in the United States was over by 1877, though racial discrimination and inequality would remain a part of American life for many decades after. In addition, the southern backlash against emancipation produced the so-called “Lost Cause” ideology espoused by such writers as Margaret Mitchell, Thomas Dixon, D. W. Griffith and President Woodrow Wilson. American literature would continue to shape the destiny of its homeland, in ways both beneficial and troubling, as the course of American history went on.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (4)

Very Informative. I particularly don't have much interest in history but it doesn't mean I don't read it. It just gives me a vibe that not everything significant that happened was recorded. But the conspiracies in history teach you a lot. And somethings that we take for-granted was fought hard for by our ancestors.

I always learn a lot from your non fiction pieces. Too bad my memory is so bad so remember everything, lol!

Interesting piece, doc

What a great piece, Doc! Thanks for highlighting the literary ties to the past and present of the US. No doubt, it will have an impact on our future, as well.