Astro-Yardies & Algoriddims: An Introduction to Jamaican Afrofuturism

From the Black Star Line Legacies of Marcus Garvey to Grace Jones and Beyond

I have an otherworldly memory from my young boyhood in Kingston, Jamaica. This was in the late 70s, and our family had recently moved there from New York City. I was navigating so many cultural shifts. It was Christmas time (my first without snow), and we were walking through a shopping plaza. Through the crowd, I heard a lively, hypnotic African drum pattern with a staccato flute or "fife," punctuating it. I looked towards the source of the sound and gasped. A small menagerie of bizarre humanoids were dancing by. I gaped at them. One had bull horns on their head, another was a dancing patchwork quilt of whirling multicolored flaps of cloth, and yet another had a horse's head. They were all very colorful, and completely outlandish. No human faces could be seen. Neither I nor my younger sister had context for any of this. These entities seemed to have just danced through a portal from another dimension. My sister and I looked quizzically at each other and shrunk closer to my parents. "What's that?" I asked. "Oh, that's Jonkanoo," Dad said with a smile. That didn't help me understand the surreal scene, but it let me know that this was a known phenomenon that people were familiar with, and it had a name. So I wasn't hallucinating. I looked around and saw other children cautiously stepping back; other smiling adults; and a lot of people just kinda going about their business like nothing unusual was happening. I learned later that Jonkanoo comes from a mixture of Akan (Ghana) and Yoruba (Nigeria) masquerade dance traditions, and is celebrated around Christmas time in Jamaica, as well as other Caribbean countries. But at that moment, I felt like I had been transported through the looking glass into the West African/Jamaican version of "Alice In Wonderland."

That experience was just one of many reasons I needed to write this piece. I wanted to include us in the rapidly growing lexicon of Afrofuturism. The buzz of Afrofuturism has been growing exponentially since the movie "Black Panther" (Marvel 2018) came to movie screens around the world. It has taken Afrofuturism out of a fertile underground and made it a global phenomenon. Caribbean folks got to beam with pride to see ourselves represented in Wakanda with actors like Leticia Wright (Shuri) from Guyana, Winston Duke (M'Baku) from Tobago, Nabiyah Be (Nightshade) the Brazilian-born daughter of Jamaica's Jimmy Cliff, and more. But we have been afrofuturists way before this.

Afrofuturism is a movement that combines sci-fi, fantasy, folklore, ancestral wisdom and technology, while envisioning futures from the perspective of the African diaspora. Jamaica is fertile ground, humming life into all of these components, to the point that it could literally just dance right up to you. It's so rich. It's in the legacy of Maroons who organized rebellions to liberate enslaved Africans, utilizing the ancient technologies of drums and abeng horns to transmit long distance messages, long before the advent of WhatsApp. It's Marcus Garvey's Black Star Line, harnessing the galactic image of a starcruiser amongst "black stars" to galvanize black people across the world to come aboard and be transported to the motherland of our ancestors, and a future with the humanity, self-knowledge, pride, cooperative economic sufficiency and the freedom we deserve. It's old timers whispering about Rolling Calf haunting the countryside at night, appearing as an unnaturally large calf with blazing red eyes and a chain link rattling around its neck. It's in our folklore, our Anansi stories about the clever trickster spider, who gave us coded messages about how to outwit massa and keep our spirits uplifted with laughter during our ancestral holocaust. It's the Honorable Rex Nettleford and the Honorable "Miss Lou" Louise Bennett-Coverly who used their bodies as receptacles to store and transmit our heritage through dance and oral history. It's Kool Herc using the technology of two turntables and two identical records to spin a whole global culture of hip-hop into existence. It's "DD" Phillips and Charles Jackson fusing the "or" from orange, the "tan" from tangerine, and "ique" from unique, to invent a new citrus fruit, the ortanique. It's in the mysterious "Sunken Pirate City" that vanished beneath the waves of what is now the Kingston Harbor and Port Royal, after a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami in 1692. This infamous anti-Atlantis was a notorious pirate hangout once known as the "wickedest city on earth." It is history that reads more like a parable or fable than a fact, and it still lays at the bottom of the harbor today.

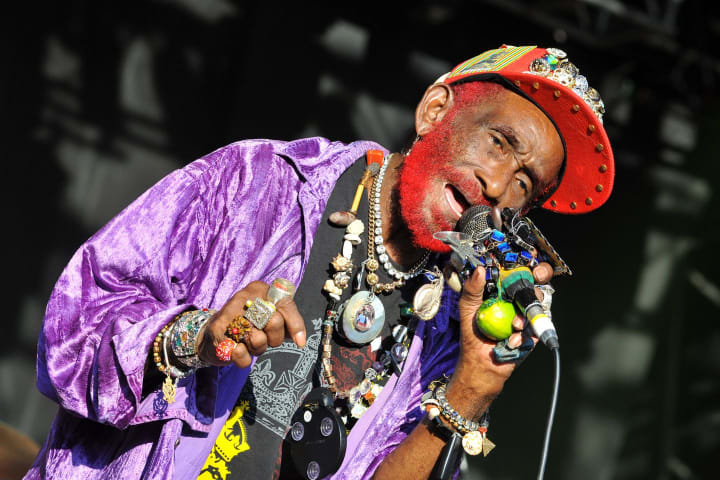

And there are many more visionaries, legends and afrofuturist avatars in Jamaica. Afrofuturists from the United States tend to claim 4 people to be foundational icons of afrofuturism. Octavia Butler, a prolific pioneer of black science fiction literature, who is also regarded as a prophetic oracle (among other things, she wrote in her 1998 novel "Parable Of Talents" about the rise of a tyrannical zealot to power who uses the phrase "Make America Great Again." Sun Ra, the avant-garde jazz icon who made music to connect with beings from other planets, and to help black people transport themselves to a space of liberation; George Clinton of the legendary space funk band Parliament / Funkadelic who not only made the famous "Mothership Connection" album, but also cites his personal experience of being abducted by extraterrestrials as his inspiration; and our very own foundational Jamaican dub innovator, Lee "Scratch" Perry, who by all means is a culture onto himself, approaching his mixing board craft as sacred sonic ritual at the helm of a spaceship. And those are just the foundational icons. People like Nnedi Okorafor, Tananarive Due, Samuel Delany, Tomi Adeyemi, Ishmael Reed, Nisi Shawl, Nalo Hopkinson, N.K. Jemisin, Nichelle Nichols, Kodwo Eshun, Meshell Ndegeocello, Janelle Monae, Jimi Hendrix, Andre 3000, Prince, Jeff Mills, Missy Elliot, Flying Lotus and even W.E.B. Dubois and many others are included in the mothership canon (for a more in-depth look into afrofuturist thought, see the foundational documentary, The Last Angel of History by John Akomfrah).

These days, our Jamaican afrofuturist icons tend to be artists who push the envelope of creative expression and identity. Grace Jones and Lee Scratch Perry represent our shining Sirius twin-stars in the constellation of contemporary Jamaican Afrofuturism. Their influence shines throughout the rest of the astro-yardie universe. Let us explore.

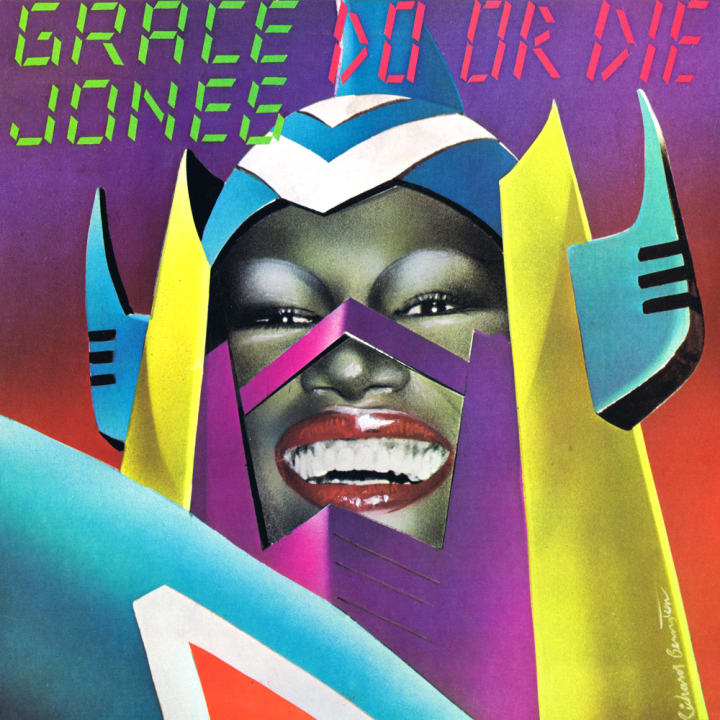

Cover for Grace Jones' 12" single "Do Or Die" (Island, 1978)

Grace Jones.

“There was also a robotic quality to my performance, a mix of the human, the android, and the humanoid…. I am not decoration; I am pure signal. I transmit."—Grace Jones, I'll Never Write My Memoirs. (Simon & Schuster, 2015)

The one and only Grace Jones. Androgynous cultural icon, fashionista, musician, movie star- and now most recently decorated with the Order of Jamaica! The Honorable Grace Jones, OJ is known for musical hits like “My Jamaican Guy,” “Pull Up To The Bumper,” and “Slave To The Rhythm,” as well as playing roles like the outrageous and untameable “Strange’” in the 1992 movie Boomerang; the formidable warrior Zula in Conan The Destroyer (1984); and superhuman assassin May Day in the 1985 James Bond: A View To A Kill. Her presence in all of these roles always feels somewhat post-human. And fiercely so. She is unmistakable, there is only one Grace Jones.

As chronicled in her memoirs, slyly titled I Will Never Write My Memoirs, Grace Jones was born in Spanish Town, and grew up in an extremely repressive and abusive situation where she was consistently beaten in the name of Christianity. As a little girl, she was sent away from this cult-like environment to stay with an aunt. Grace watched with fascinated horror as her aunt put on make-up, an act for which Grace would have gotten a severe beating. Why? Because only some kind of immoral sexpot would wear make-up in the eyes of Jesus. Her first subversive act of daring to think for herself, was trying on make-up with trembling fingers. Grace Jones went from being a repressed and frightened little girl to becoming arguably one of the most liberated women on the planet. She’s definitely also become one of the more potent archetype’s of the Minster’s Daughter, adopting a free-spirited “try everything at least once” mantra, whether talking about creative process, sex, or substances (you have to read her book to believe it!) In her rejection of being repressed and controlled, she also broke many social norms, especially around gender. One could say that she has decolonized herself of the rigid gender boundaries historically imposed on black Jamaican women.

Stas Schmiedt, a Miami-based, black nonbinary organizer and gender theorist had this to say about gender and afrofuturism:

“Precolonial black gender roles were often more expansive and inclusive than today's rigid gender binary. Although we are socially reprimanded for deviation most of us just don't fit into today’s gender roles because they were not made for black and brown bodies or culture. Black trans* and gender non conforming people are maintaining a lineage of gender expression that have deep roots in our culture, while giving us a glimpse into an afrofuturist future of gender liberation. Afrofuturism provides a lens to redefine what progress looks like by reclaiming concepts that white colonial theory deemed "uncivilized" and embracing them as a more evolved and innovative way of being.”

Indeed, Grace Jones continues to be an innovator of self along lines of gender expression and creativity. Being the counter-cultural rebel she is, there were unfortunate repercussions to returning to a homeland that is traditionally very strict about gender roles and gender expression. Grace Jones was unfortunately, initially made to not feel safe on visits back to Jamaica. She didn’t have the easiest time being embraced by Jamaican community either, she was a cultural outlaw. We sadly didn’t really claim her at first. And trust me, Jamaicans love to big up any of us who make it into the international limelight.

I remember wondering about this striking and eccentric black woman on the Grammy’s during the 80’s, but never knew she was a born Jamaican until sometime in the 90’s. I was shocked that it took me so long to find out, even living in Jamaica where we all watched those 80’s Grammy’s, and then talked about it at school. Never was our Grace mentioned. Much later, while going to hear KAT C.H.R. do a tribute to rock tribute to Michael Jackson in Kingston’s Red Bones Café (it was 2009, he had just passed) I went to order a drink, and saw the iconic Grace Jones Nightclubbing album framed and mounted behind the bar. I looked at her “blurple” skin, sharp shoulder-padded black blazer, and the cigarette defying gravity dangling from her lip. There was something about this moment I couldn’t put my finger on, and then it came to me. I realized it was the first time I had ever seen Grace Jones acknowledged in a public Jamaican space.

Nowadays, I hear her being more claimed by us. Grace herself has made peace with Jamaica, and often spends time in Porty (Port Antonio, Jamaica) to relax. Getting the Order of Jamaica from the government must have also felt like sweet recognition a long time coming!

Her music blended soul, reggae and art rock in ways that had not been done before, and she continues to push creative and social boundaries, as documented in her newest documentary, Grace Jones: Bloodlight And Bami. Her transcendence of gender, futuristic treatments of Jamaican music, portrayals of evocative fantasy characters, and “androgynous android” persona ushers her easily into the halls of Jamaican Afrofuturism.

Lee 'Scratch' Perry performs in Wiltshire, England. (C Brandon/Redferns via Getty Images)

Lee “Scratch” Perry, the dub pioneer who has described himself as the “Jamaican E.T.” is quoted as saying:

“I see the studio must be like a living thing, a life itself. The machine must be live and intelligent. Then I put my mind into the machine and the machine perform reality. Invisible thought waves - you put them into the machine by sending them through the controls and the knobs or you jack it into the jack panel. The jack panel is the brain itself, so you got to patch up the brain and make the brain a living man, that the brain can take what you sending into it and live.”

Yu hear? Scratch continues to be considered a sonic shaman astronaut of sorts in the Jamaican music community. And I don’t use the oft-overused term “shaman” lightly:

“Perry was known to run a studio microphone from his console to a nearby palm tree, in order to record what he called the ‘living African heartbeat.’ He often ‘blessed’ his recording equipment with mystical invocations and other icons of supernatural and spiritual power such as burning candles and incense, whose wax and dust remnants were freely allowed to infest his electronic equipment. Perry was also known to blow ganja smoke onto his tapes while recording, to clean the heads of his tape machine with the sleeve of his T-shirt, to bury unprotected tapes in the soil outside of his studio, and to spray them with variety of fluids including whiskey, blood, and urine, ostensibly to enhance their spiritual properties.” -Michael Veal, from “Dub: Soundscapes and Shattered Songs In Jamaican Reggae.”

Scratch embodies the “Mad Scientist” archetype, engaging his mixing board like a living cyborg and control panel for a sonic spaceship. He inspired other dub icons to follow suit in persona, giving rise to his peers, Scientist and Mad Professor. He was also known to work with the highly acclaimed King Tubby, the undisputed crowned king pioneer of dub. Lee Scratch Perry’s esoteric techniques allowed him to have a signature sound that could not be duplicated, and made him be sought after by the likes of Bob Marley and The Wailers, Junior Murvin, The Heptones, Max Romeo and more (and much later in his career, acts like Bill Laswell, The Orb, Moby, Keith Richards, and George Clinton). Some of his most loved work came from his infamous laboratory of ritual and music, the Black Ark Studio. The Black Ark also evoked the afrofuturist imagery of a vehicle destined to other liberating realms. Garvey had the Black Star Line. George Clinton had the Mothership Connection. Scratch had the Black Ark Studio. The Black Ark is where he perfected his craft as a dub pioneer. At the helm of the Black Ark, or any mixing board he had access to, he would create time and space warps out of musical frequencies. Random eccentric sounds like a cow mooing or a baby crying to add surreal signposts along the journey. Delays and reverbs would literally transmit echoes from the past into the present like the voices of ancestral griots. The listener would be transported into vast and buoyant alternate realities, left to float in zero gravity orbits, and wherever else the Jamaican E.T. schemed to take us as he took the wheel of the Black Ark.

Dub music itself, the original remix, started with making these spacious instrumentals or “versions” of rocksteady and reggae tracks in the 1960s. Dub went on to influence many people and music genres around the world. Dub begat ambient electronica, jungle, atmospheric drum n’ bass, dubstep, dub techno, grime, two-step, reggaeton, moombahton, shoegaze, trip-hop, tropical bass… and no dance single in the 80s could be complete without a dub mix. The dub mixes and the extended mixes of disco and post-disco tracks, in turn, begat house music in Chicago in the late 70s. Scratch is one of the original architects of this now ubiquitous sound that has transformed into different algo-riddims worldwide.

For the uninitiated, his album “Arkology” (1997) is the quintessential collection of his most loved work from The Black Ark. It includes 70s hits like Junior Murvin’s “Police And Thieves,” Max Romeo’s “War In A Babylon,” Lee Scratch Perry’s “Curly Locks,” “Roast Fish & Cornbread,” and many more, including dubs of several tracks. For a strictly dubwise tour of the Black Ark’s trajectories, check “Black Ark In Dub” (1997). And for a trip back to when Scratch and Bob were making music, I would recommend the Bob Marley vs. Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry: The Best of the Upsetter Years 1970-1971 compilation.

Also, the man is in his 80s and still touring! You can still catch the Jamaican E.T. live and direct!

And there are many others reppin Jamaican Afrofuturism. Limber up your browser tabs, and strap in for the express shuttle through some more of the astro-yardie galaxy!

Visual Artists

"Nickii portrait" by Kokab.

First stop, visionaries of light and color. Kokab Zohoori-Dossa (@kokabzd) lives New Zealand when not in Jamaica, and makes, in the truest sense, fantastic portraits. She will even do commissioned portraits, transforming folks into creatures of myth and alternate dimensions (as pictured above). She says:

"My influences come from the people. Black people, around me and the stories and media I grew up with and still watch. I read a lot of fantasy and I like stories of all kinds and in all forms, like movies, comics, TV shows, etc. I think we're too interesting to not have a multitude of depictions of black people of various types. I also love nature, plants and animals, so that is also a clear influence on my work. if my art could be a portal to anywhere, I would say I would want it to be a portal to a place where everyone can be who they are, full of magic, innovation and respect.”

She is a busy bee, juggling murals, commissioned portraits, children’s books, merch, and even recently did artwork for the Sean Paul and Jhene Aiko single “Naked Truth.” Expect to see more from this one!

Paul Lewin "The Visitor."

Paul Lewin lives in Oakland, California where he often has highly anticipated exhibitions. He was bequeathed possibly one of the highest honors in the afrofuturist universe, and that is to have his work be featured on the reissues of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents. Paul responded by saying, “ I have no words to describe how honored I am to have my art on the cover of these books. Octavia Butler and her works have meant the world to me for many years now as she has meant the world to so many others. She has inspired so much of my art and thoughts about the world. I have mentioned her in just about all my interviews over the years.” He is currently planning to start an art mentoring program in Oakland, and the social mediasphere rejoiced at this news when he announced it. He also goes on to say:

“In early Afro-Caribbean communities artistic expression was a vital tool in the struggle against colonization. It was also a way of keeping the ties to our ancestral past strong. Creativity and storytelling were a means of cultural survival in unfamiliar lands. I find this in many ways similar to what we, as part of the diaspora, experience today. Growing up on a steady diet of tv, video games, sci-fi and fantasy, I found myself submerged in a world where i saw very little representation of characters similar to myself. Art allowed me to create new stories based on my own experience. Over the years my work has been influenced by indigenous folklore, tribal cultures, religion, and ancient societies. Old folktales, legends, and rituals re-imagined through new experiences and new ideas of self. Much of my work takes place amidst the backdrop of sci-fi and fantasy. I like to mix traditional Caribbean and African motifs with surreal visions of nature and the ancestry that surrounds us daily.”

Click here for his mesmerizing website, and you can also follow his various social media portals from there.

Taj Francis "Armor I"

“…the second son, the middle child, constantly seeking INSPIRATION, artist and child of THE MOST HIGH, Jamaican Born, Universe Bound, Exploring the Infinite and then Some…”—Taj Francis

Proud Jamaican son, digital and visual artist Taj Francis. His work is immediately identifiable, with colorfully contoured characters that seem to come from different beautiful and mystical dimensions. His work has quickly become sought after on the island and beyond, to say he is busy is an understatement. He’s created murals in association with Paint Jamaica to help bring new life and color to disenfranchised communities in Kingston; he’s getting a clothing line together; done album covers for the likes of Protoje, and even an animated video for the dub version of Chronixx and Protoje’s smash hit “Who Knows.” And more! Be sure to follow him and see what else he is up to!

Moving Visions

Madge Sinclair (April 28th, 1940 – December 20, 1995) on the left as Queen Aoleon in Coming to America (Paramount Pictures, Eddie Murphy Productions, 1988), and on the right as Captain Silva La Forge in Star Trek: The Next Generation. (Paramount Television, 1993)

Madge Sinclair. Before Wakanda came to the big screen, there was Zamunda! A beloved staple in Black Cinema, Coming to America (1988) portrays the journey of the very sheltered and pampered Prince Akeem (Eddie Murphy) on a quest for love from the fictional African country of Zamunda to the USA. Madge Sinclair played his mother, Queen Aoleon, an analogue to Angela Bassett’s role of Queen Mother Ramonda in Black Panther (2018). Madge Sinclair also played roles in other sci-fi, fantasy, occult and horror productions:

- The title role of Tituba the witch in The Witches of Salem: The Horror and the Hope (1972)

- Lorraine Michaels in sci-fi series Starman (1987)

- Lucille in the horror series Tales From the Crypt (1992)

- Geordi La Forge’s mother, Captain Silva La Forge in Star Trek: The Next Generation (1993)

- The voice of the queen lioness Sarabi in Disney’s classic, The Lion King (1994)

She had a very, very extensive filmography which also included a part in the forever classic original Roots series (1977). She played Belle Reynolds, Kunta Kinte’s wife, and was even nominated for an Emmy for her portrayal. Besides Coming to America, she was most well known for her roles as Ernestine Shoop in the 80s television series Trapper John, MD (1980-1986), and Leona Hamilton in the movie Cornbread, Earl, and Me (1975). She finally took home an Emmy for her role as Empress Josephine in the provocative cops vs. black nationalists ABC series Gabriel’s Fire (1990-1991). After proudly representing in over 40 productions, Madge Sinclair went to join the ancestors in 1995, concluding her battle with leukemia for 13 years. Thank you esteemed afrofuturist ancestor, for your regal, magical, and dignified portrayals of Jamaican womanhood for the world to see!

Other Notable Moving Visions

DVD cover for Haile Gerima’s Sankofa (Channel Four Films, Ghana National Commission on Culture, Mypheduh Films, 1993, 1994)

Jamaican dub poet Mutabaruka plays one of the key roles in Haile Gerima’s Sankofa, where an African American fashion model is whisked back in time from a photo shoot in contemporary Ghana to the horrors of slavery on a plantation in the Caribbean. (Trailer.)

Paul Campbell in the 1991 Jamaican cult classic The Lunatic. (Island Pictures, 1991)

Anyone who was in Jamaica in the early 90s most likely remembers the excitement around this film! In The Lunatic, Paul Campbell plays the lovable street urchin and village “madman” Aloysius, whose name grows hilariously longer as the film progresses. Aloysisus’ best friend is a tree, and they spend their time having long conversations waxing philosophically about life.

Book cover of Nalo Hopkinson’s novel, Brown Girl in the Ring (Warner Aspect, 1998) and promotional poster for Sharon Lewis’ movie inspired by the book Brown Girl Begins. (urbansoul inc. 2017)

This one’s a two-fer! Jamaican-Canadian Sci-fi author Nalo Hopkinson’s first novel, Brown Girl in the Ring was reinterpreted into a film called Brown Girl Begins by Caribbean-Canadian filmmaker Sharon Lewis. Both pieces are full of intrigue, afro-caribbean folklore and magical realism. Click here to see clips from the film, and hear both Nalo Hopkinson and Sharon Lewis talk about their inspiration and creative process!

Promotional graphics for Kibwe Tavares' Robots of Brixton (Factory Fifteen, 2011) and Jonah (Factory Fifteen, Jellyfish Pictures 2013)

British-Caribbean Filmmaker Kibwe Tavares was studying architecture when he decided, self-taught, to make his first animated short film, Robots of Brixton (2011). The sci-fi reinterpretation of the UK riots of Brixton replaces the mostly Jamaican and black residents with an oppressed robot class. It became an instant hit. In just two months, the upload of his film clocked half a million views. It also earned Kibwe a Sundance animation award, fresh out the gate. He continued to be a Sundance darling with his second film, Jonah (2013), which while live action, still boasted Kibwe’s now signature special effects and animation wizardry. Filmed on location in Zanzibar, Jonah is what you could call “a big fish story.” Inspired by their encounter with a fish of mythic size, the protagonists struggle with their friendship, and the pushes and pulls of tourism economy, globalization and commercialization. Kibwe continues to make films, and he is the co-founder of Factory Fifteen, a creative studio that offers animation, film direction, and architectural visualization and design. Be sure to check out these shorts, and more on his website, all hyperlinked above.

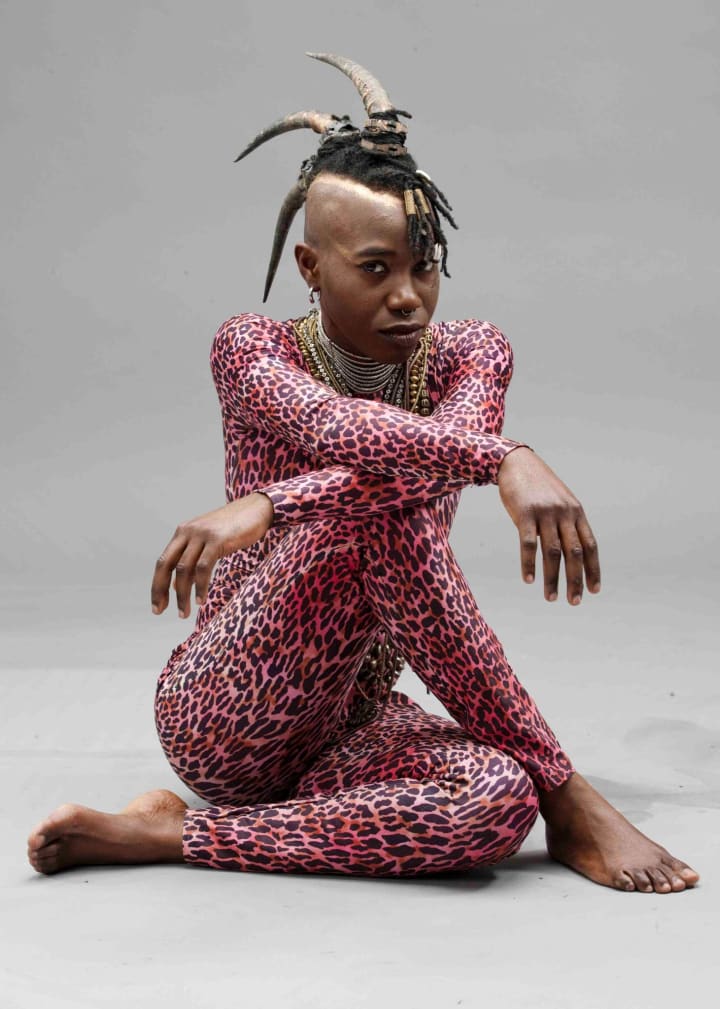

Aesthetic Warrior Scions of Grace Jones

Photo of d'bi.young anitafrika by Noncedo Charmaine

At 13 years of age, d’bi looked up gleefully at three bright shining stars. She was convinced they were looking over her. She made a prayer pact with these celestial bodies: “If you three stars grant me the wish of being a storyteller all my life, I promise you I will be the best human being I can be.”

And the rest is history for this starchild. Long hailed as an afrofuturist icon in Canada, Kingston born d’bi.young anitafrika is a multi-pronged firey force of nature. Storyteller, dub poet, actor, playwright, activist, educator, scholar of “decolonial queer black feminist praxis”- and even a comic book supershero- the expression of her fiercely creative spirit is vast. For her though, it all comes back to poetry. “At the end of the day, I’m a poet. Everything that comes out of me, plays, music, poetry, theory, all of that for me is all poetry.”

D’bi looks very strongly to her mother, dub poet pioneer Anita Stewart as a premiere muse and all-around superhuman. Anita Stewart studied at the Jamaican School of Drama, and was a member of Jamaica’s first dub poetry group, Poets In Unity. In 1985 Anita Stewart went on to write a thesis called “Dubbing Theater: Moving Dub Poetry into the Theatrical Realm,” which focused on four elements of dub music, politics, performance and language. D’bi grew up immersed in all of this, she recalls being wide-eyed with deep love and admiration, watching her mom weave theatrical universes like “some sort of incredible, radiant, otherworldly being.” D’bi is truly a product of her environment, she watched her mom be a dub poet, scholar, teacher, mom, community worker- all while surviving in the working-class Kingston neighborhood of Maxfield Avenue. D’bi lives what she has known her whole life. She lives what has always been modeled to her. She even went on to form her own methodology, the anitafrika method, using her mom’s thesis as the foundation.

D'bi has other influences too. When asked about Grace Jones, she says: “When I think about Grace Jones, my heart starts to flutter and a huge smile creeps across my face, and I feel in my body that YES. There is space in the world for me.” D’bi went deeper in contextualizing this, saying: “As a survivor of sexual abuse, what is the impact of sexual abuse on my erotic? I don’t know, but what I do know is that she also very much created a space for me to welcome and celebrate the divine erotic, my queer black feminist erotic. It’s important to have people, figures, elders, leaders, whatever you want to call them, people who can mirror what is possible. That it is possible to be in one’s body and to negotiate and renegotiate one’s own liberation, sexual liberation, aesthetic liberation, and stylistic liberation.”

Yu hear? D’bi also added with an excited lilt in her voice, “and she is so stylish and sexy!"

In closing, d’bi thankfully mused on how her pact with the three stars have been honored: “I get to be a storyteller and make magic, and take people on a magical journey. On this journey, time stops, and we are all transported to somewhere unnamable inside and outside the self.”

To be transported into d’bi’s powerful stories, you can purchase her albums, collections of poetry, comic books, watch videos of her performances, or even catch her live by following her calendar (all this and more available at her website). Her upcoming feature is at the Black Technoscience Conference at the University of Toronto Canada—this star blessed storyteller is afrofuturist to the bone mi a tell yuh!

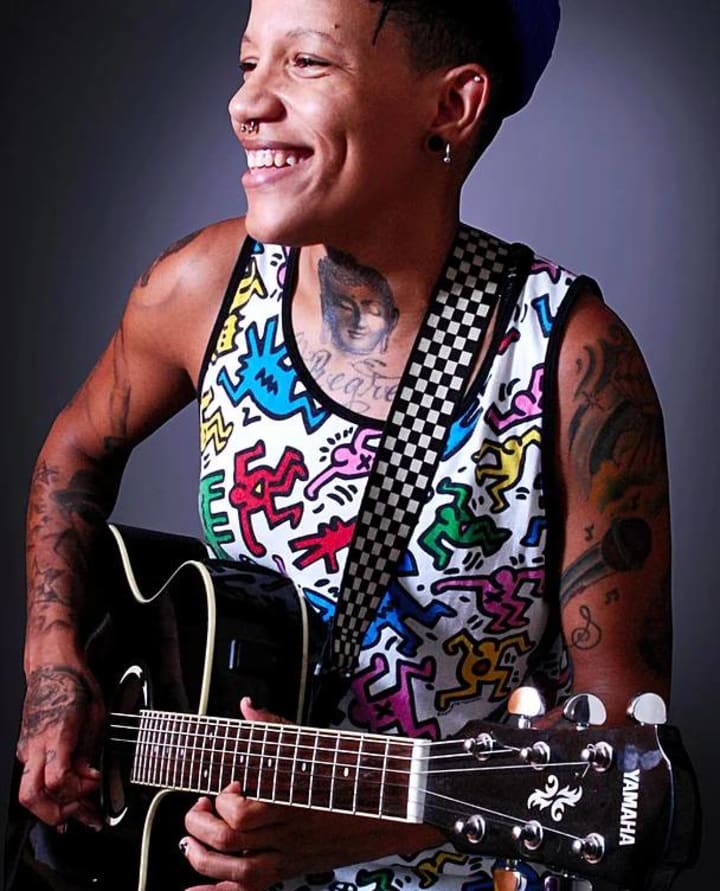

KAT C.H.R.

KAT C.H.R. embodies so much that is Jamaican Afrofuturism. The tattooed singer gives a very punk presence while playing guitar, and their music runs the gamut from rock, to soul, to reggae, and honestly other vibes hard to classify. Sometimes sounds like Tricky. They continue the Jamaican afrofuturist tradition of transcending gender, and they unapologetically go by the pronouns “they” and “them” while living in Jamaica. They go on to say: “If my art were to take me anywhere, I would want it to be to a dimension where all people are free to be who they are. Transport me to a world where the sound of everyone marching to the beat of their own drum drowns out all fears.”

And that is the context I first met KAT C.H.R., marching to the beat of their own drum, doing a rock-infused tribute to Michael Jackson at Jamaica’s Bohemian Red Bones Café (the same spot I first ever saw a mounted picture of Grace Jones in Jamaica). KAT has been a part of the burgeoning Kingston alternative scene for quite some time (I saw them on stage in 2009 as part of Crimson Heart Replica, which is what C.H.R. stands for), and since then, their international appeal has been growing, doing more and more performances outside of Jamaica like touring the US, and even being a feature at San Francisco’s LGBTQ Pride showcase in 2016.

KAT also shared some of their thoughts about Grace Jones: “Since Grace Jones is an androgynous woman, I’ve always identified with her. Especially because she’s a fucking rock star on top of that, and proud of being Jamaican. She has influenced and strengthened me. And that representation piece is so important. I see her and I see strength. She is so avant-garde, such an artist. A pillar of reinventing self over and over, breaking every mold.”

A recent accomplishment for KAT is also very relevant to this article… they got to assemble into a sonic afrofuturist Voltron and collaborate with Lee “Scratch” Perry!! Check this link for the new track “Suit A Rebel,” featuring DejaVilla, Lee Scratch Perry, and KAT C.H.R. Yes!

You can follow KAT on Facebook and Instagram for videos, tunes, concert dates, musings on life and more. And here is their EPK for a nice compact video experience of the KAT C.H.R vibe. You are going to be hearing more about this one, trust!

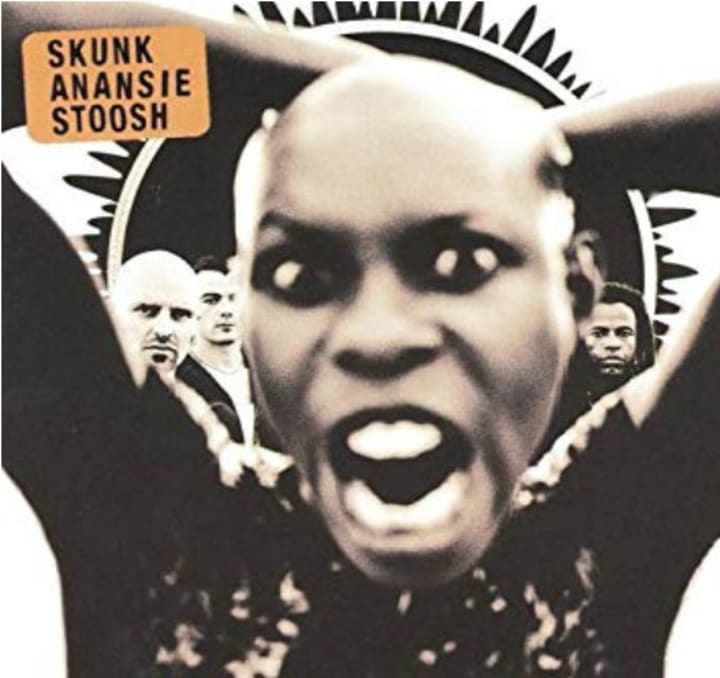

Cover art for the Skunk Anansie album Stoosh (Epic Records, 1996)

I didn’t interview Skin (Deborah Dyer), the frontwoman of the foundational punk Britrock group Skunk Anansie, but I definitely felt like she needed to be included here. I mean, is the androgynous Grace Jones warrior aesthetic apparent or what?

Skin, Born Deborah Anne Dyer in London, has another similarity to Her Graceness, they both grew up in a very strict Christian Jamaican household. However, her grandfather owned a very popular speakeasy in London (called a “shebeen” there), whereas a young girl Skin saw the likes of Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay), Peter Tosh and Bob Marley come through. This was some of her first exposure to radical black thought and music. She is quoted as seeing Bob Marley as her “first musical hero,” and that being a source of Jamaican pride for her.

As a teenager, Skin discovered ska. It struck a chord of familiarity, while being channeled through “these white, skinny boys, playing black music.” It was through these very same white skinny ska boys that Skin discovered guitars, and that launched a whole new connection to music for her. She went on to play in a band that was a not very successful pre-Skunk Anansie iteration, before forming the Skunk Anansie that became the iconic Britrock band.

Skin drew from Jamaican folklore in naming the band. Anansi is the fabled trickster spider that originally came from Akan/Ghanaian stories. Skin recalls hearing the Honorable Louise Bennett-Coverley (Miss Lou) tell Anansi stories on TV, and she wanted to honor this by incorporating it into the band’s name. “Skunk” was reportedly added to the name to “make it nastier.” And voila, in 1994, Skunk Anansie was born.

Their sound has been described by Allmusic as “an amalgam of heavy metal and black feminist rage,” and Skin and band member Ace cite dub, reggae, electronica, hip-hop, world music, The Sex Pistols, and Blondie as notable inspirational influences. Skin has also described her sound as “clit-rock.” Their first three studio albums, Paranoid & Sunburnt (1995), Stoosh (1996), and Post-Orgasmic Chill (1999) went on to sell over 4 million copies. The singles “Weak,” “Hedonism,” “Charity,” and (the anti-Nazi song) “Little Baby Swastikkka” remain some of their most popular tracks, and their music videos gave them an even wider audience.

Skunk Anansie’s songs were mostly written by Skin, and many have powerful political punch to them. Skin is quoted as saying: “I’m a female, I’m also black. I’m also gay, bisexual, I have fluid sexuality. I’m also from a very poor background—those four things really created my character and my identity…and because of all of those things, because I’ve had knives thrown at me from all directions because of one thing or another, I have very open eyes.”

The band split up in 2001, and Skin went on a solo creative path. She now wears many hats, vocalist, techno DJ, and she’s even a skilled interior architect. She was recently honored in the UK’s Women In Music Awards hosted by Music Week, where she received the 2018 Inspirational Artist Award, and was hailed as “one of the most iconic and unforgettable stars of her generation.” Tings a gwaan!

British Astro-Yardies

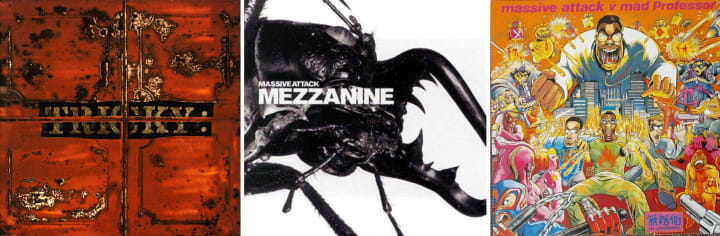

Cover art for Tricky's Maxinquaye (Universal Island Records, 1995), Massive Attack's Mezzanine (Virgin Records, 1998), and Massive Attack v. Mad Professor's No Protection (Wild Bunch Records, 1995)

Jamaican music influenced the world. And our British family like Skunk Anansie and others continue to take it to the next level. Adrian Thaws aka Tricky was born to an Anglo-Guyanese mother (Maxine Quaye) and a Jamaican father (Roy Thaws) who operated a successful sound system in Bristol. After being a member of the band Wild Bunch, which evolved into Massive Attack, Tricky became known as one of the pioneers of “trip-hop” in the 90s when he busted onto the scene with his solo debut album Maxinquaye (named after his late mother). His gravelly voice alongside the ethereal vocals of Martina Topley Bird, flowed over ganja-drenched sounds that fused dub, art rock, soul, and hip-hop. The album took the world by storm, and he was plunged into the international limelight, which included an acting role in the widely-acclaimed sci-fi film, The Fifth Element (Gaumont, Columbia Pictures 1997) where he was cast as the shady mutant henchman known as Right Arm. Tricky was reportedly challenged by the sudden international fame, and his unique music being pigeonholed into a genre. His highly anticipated second album "Pre-Millenium Tension" started to veer away from the "trip-hop" sound, with the smash single "Christiansands" being the closest to his original cadences. He often paid tribute to golden era rappers from the US, a Slick Rick sample can be heard looping in the background throughout "Christiansands." He also covered Public Enemy's "Black Steel" on "Maxinquaye," and worked with Martina Topley-Bird to turn it into a headbanging afropunk rock track. While he looked respectfully to US rappers, he had his very distinct, very different rapping style, and he also did not embody the rigid gender roles that are often in US hip hop culture. He appeared in the inner sleeve of the "Maxinquaye" album wearing a dress, and he would casually wear makeup, often adopting a more goth presence that also appeared in the tone of some of his music. More of that afrofuturist transcending of gender! After making a name for himself with his eclectic, complex, haunting, layered and smoothed out "trip-hop" sound; and collaborating with people like Bjork, Neneh Cherry, PJ Harvey and more recently Grace Jones; he took his music into edgier, punkier territory. He remains a highly sought-after act for festivals like Afropunk, and remains the reluctant king of trip-hop.

As mentioned, prior to his solo career he was also a member of Massive Attack. It has been said that Tricky, Massive Attack, and Portishead are the holy trinity of trip hop. And the first two of those have a very strong Caribbean background. Besides Tricky having been a founding member, Massive Attack also boasts the vocals of esteemed elder Jamaican reggae crooner, Horace Andy; and founding member Daddy G, also has Caribbean parents. While they have several studio albums with star-studded cameos like Tracey Thorn from Everything But The Girl; Sinead O’Connor; Elizabeth Fraser from Cocteau Twins and others, fans tend to squabble over which of their first three albums is their favorite: Blue Lines, Protection, or Mezzanine. I’m a Mezzanine kinda guy. There are many amazing tracks on that album (all of them, pretty much!) but I feel I should point out Horace Andy’s remakes of his own classic reggae tunes: The album kicks off with “Angel,” the brooding remake of his 1973 hit “You Are My Angel.” It starts with smoldering downtempo bass tones, and expands into an epic rock guitar infused opus. Later in the album, his 1975 hit “Quiet Place” is remade into a twilit forest of echoing beats and bass as the song “Man Next Door.”

While I’m in the Mezzanine camp, the No Protection album, a dub treatment by Mad Professor of the Protection album, remains an afrofuturist classic. Not only musically, but with an album cover depicting members of Massive Attack and Mad Professor towering over a cityscape engaging in comic book style, intergalactic sci-fi warfare, evoking an afrofuturist “soundclash” metaphor of Jamaican sound systems here to sonically destroy all other sound systems. It is worthy to note that Massive Attack has recently announced a Mezzanine anniversary tour, and Elizabeth Fraser will be touring with them to sing hits like “Black Milk” “Group Four” and “Teardrop” ("Teardrop" probably being the biggest hit from the album). People are scrambling to get tickets, not only because of the significance of this being the 20th anniversary of an album that has been included in Rolling Stone’s Top 500 albums of all time, but also because Elizabeth Fraser is touring with them, and she hasn’t been on stage since the 1997 breakup of her foundational ethereal gothic, shoegaze band, Cocteau Twins. It promises to be monumental!

Cover art for Steve Spacek's Spaceshift album (Sound In Color, 2005) and "Ring Di Alarm" single as Beat Spacek (SPA, 2017)

Steve Spacek: this British Astro-Yardie has been pushing the creative envelope since 1996 when he was in the music group Spacek. Their albums “Curvatia” and “Vintage Hi-Tech” were both future soul masterpieces, which included collaborations with Mos Def. Style Magazine described Spacek as “The Radiohead of Soul.” In 2005, he went solo as Steve Spacek with his debut album “Space Shift”, which featured a single produced by J Dilla called “Dollar.” TUNE! Steve Spacek began to earn comparisons to D’Angelo, Curtis Mayfield and Massive Attack, and Rolling Stone hailed him as “giving new meaning to the phrase space funk.” He went on to reinvent himself into constellations of aliases and side projects, with names like Beat Spacek, Black Pocket, Supadread, Africa HiTech and more. There’s a lot to explore, if you are not familiar, I would start with the Steve Spacek’s “Spaceshift,” Spacek’s “Vintage Hi-Tech” & “Curvatia,” Beat Spacek’s “Modern Streets,” as well a Beat Spacek cover of Tenor Saw’s classic “Ring Di Alarm” that is completely overhauled into an airy, percussive and bassy electronic tune that sounds like he is sweetly serenading a robot dance party in zero gravity. Run di track...

Yardie Algo-Riddims

Cover art for the Boney M album Nightflight to Venus (Hansa Records, 1978)

Boney M, Nightflight to Venus. In 1978, a lot of Jamaicans had this album. Oh, did we ever. The hits were “Rivers of Babylon” and “Brown Girl in the Ring,” both covers of dearly loved Jamaican songs; the first a Rasta anthem, and the second a girl's ring-game song. But the rest of this album- whoa! Space funk, Euro-disco, reggae and pop rock fused together like we hadn’t heard before. The title track “Nightflight to Venus” was probably my introduction to afrofuturistic Caribbean music. The album kicks off with a vocoded robotic voice announcing “Ladies and gentlemen. Welcome aboard the Starship Boney M four-hour first passenger flight to Venus. Ready for countdown. 10…9…8….” The women’s voices waft in like an ethereal choir, singing “Nightflight to Venus” in octaves that rise higher and higher as the countdown approaches zero. At liftoff, we hear the booster rockets and a slow drum riff that increases in speed until it steadies out into a rolling dance beat. We are taken on a cruise towards the stars, at times taking evasive maneuvers to avoid asteroids. This remains one of my favorite tracks on the album. I used to love being transported by this song as a child, and me and my sister and friends would dance around like satellites bouncing around in space.

This album was #1 on the UK billboard chart, and was an international hit as well. At the time, “Rivers of Babylon” was the second highest selling single of all time in the UK, it wasn’t just mashing up Jamaica! They had several chart-topping hit songs and albums, selling over 80 million copies altogether worldwide, making them one of the top-selling acts of the 1970s, next to acts like ABBA, Donna Summer, and the Bee Gees. They were founded in West Germany, and of the original members, two were Jamaican (Liz Mitchell and Marcia Barrett), one was from Montserrat (Maizie Williams), and the wild dancing frontman was Dutch with Aruban ancestry (Bobby Farrell). Boney M. Caribbean space pop to di worl!

Promotion graphic for Sankofa Sessions @thesankofasessions

Various music revivals are happening in Jamaica. A roots revival was spawned on the beaches of Bull Bay at the Rasta surf camp and live performance venue Jamnesia, where musicians like Chronixx, Protoje, and Jah9 cut their teeth and went on to become new ambassadors of roots and conscious reggae to the world. There is also Dub Club, way up in the hills overlooking the Kingston skyline, where founder-selector Gabre Selassie went against all conventions, saying he is going to throw an event where he won’t play dancehall, only dub, and roots. No one thought it could be successful. Now it is an institution, with old school DJs and producers like King Jammy’s coming through to mix live.

Sankofa Sessions is another type of renaissance, providing another space of uplifting sounds, and another approach to the roots mentality. Billed as playing “electric afrobeat cultures," DJ and event organizer Iset Sankofa plays not only dub and roots, but also afrobeats, afrohouse, and other forms of music steeped in African roots. She goes on to say:

“In a way, we are a sort of time capsule. Past, present, future as Sankofa does suggest. So we say "the past, the present, the remix." These icons, these platforms are all my influences and futurism. I always work to define another kind of Africa, beyond the CNN and beyond the National Geographic. One that is art, ancestry, mystery and beauty in itself . That is the African Aesthetic as I like to call it. Expect to feel lifted. Sounds like a sonic rebirth on a Tuesday night. Audio church.”

You can follow Sankofa Sessions at @thesankofasessions. Be sure to go get your audio church at the Kingston oasis known as Stone’s Throw Bar @stonesthrowbarja if you are there on a Tuesday! And other nights too, many more cultural delights await there.

logo for Future Sound of Reggae (FSOR) and cover art for Transdub Massiv's Negril to Kingston album (FSOR, 2005)

Kingston’s Future Sound of Reggae label has been growing steadily in it’s influence, with artists like Cuban-Jamaican artist Arii Lopez flowing fluidly from Jamaican patois to Spanish in her songs; soulful songstress Sezi; modern ska-pop astronaut Yaksta; and the fly ambassadors of new wave reggae, Skygrass. Co-founder Steve Urchin says: “mining the creativity of Jamaican musicians who are not the ones being focused on, that is what future sound of reggae is all about. ” FSOR has also now become the home for Transdub Massiv, whose 2005 debut “Negril to Kingston City” became a future-dub cult classic, mixing ambient soul, roots and dub together in innovative and organic sounding ways. Executive producer of Transdub Massiv, Steve Urchin says “You know, it’s funny, because 12-13 years ago, Transdub Massiv was ahead of its time. A friend of mine recently called me and said ‘hey, you know I listen to the album today, and it still sounds correct, bro! In fact, it still sounds like it’s from the future!’” And indeed it does. Urchin has reason to beam with pride. I myself was blessed to be involved in the project as co-producer DJ fflood alongside mtfloyd. The album features Meshell Ndegeocello on bass, Sizzla, Ce’cile, Tami Chynn, Jovi Rockwell, Rootz Underground, and more. Also, singer Farenheit sings on “Moonrise Dub,” as someone sending a love message while orbiting the earth from space. I mean, it doesn’t get more afrofuturistic than that!

Be sure to follow @fsormusic for updates on new Transdubbian offerings to come (finally!) as well as other cutting-edge vibes.

Thank you for coming along for the ride, reader! I leave you with another offering, one of my latest ffloodmixes, the second in a series called "avant yardie 2." I like to say that it's for afro-caribbean music purists and futurists. Enjoy. :)

I hope this foray into Jamaican Afrofuturism has been informative and fun, and that you continue to enjoy the sights, sounds, and visions! May it inspire liberating and creative futures for you too. Walk excellent, bless.

About the Creator

Richard Wright, MA

Richard has a Masters in Expressive Arts Therapy; trained with MenCanStopRape; and facilitates healthy masculinity / consent culture workshops. He DJs, paints, and writes afrofuturist fiction too. For more: www.richardmwright.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.