The Fairy Tale That Never Was

The story behind the iconic photo

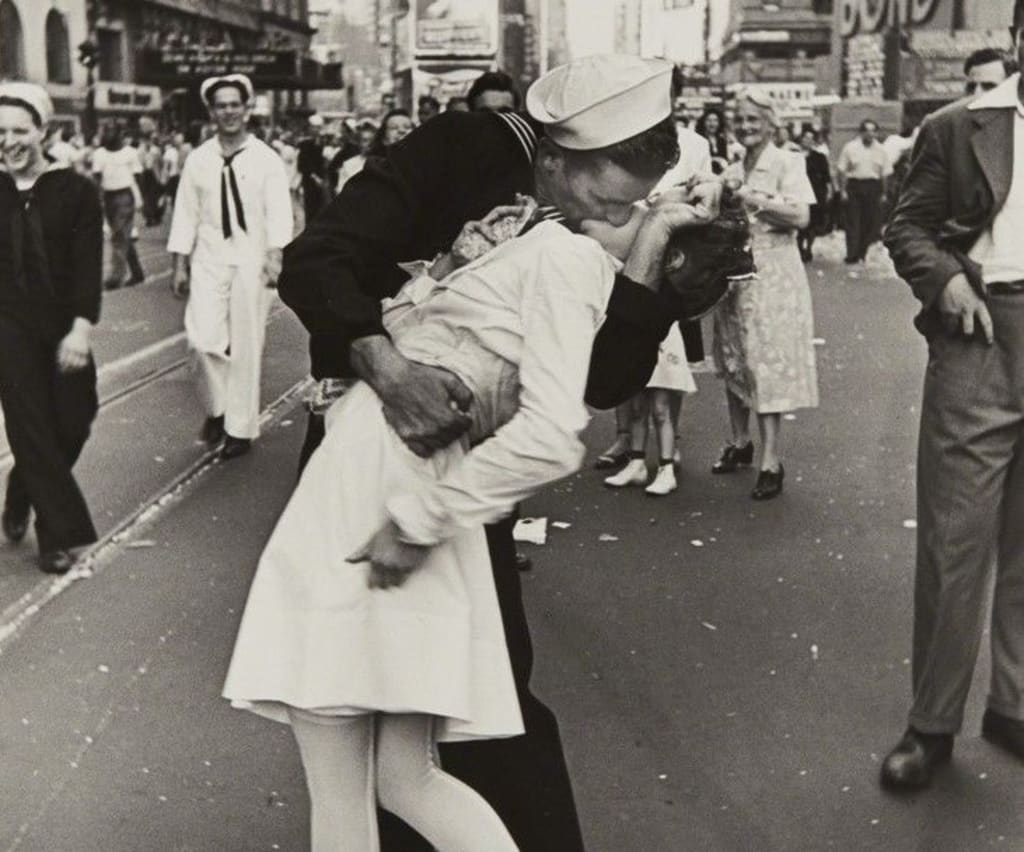

It’s an enchanting photograph. The black and white image of “The Kissing Sailor” romanticizes Americans’ joy and relief at the announcement that World War II was coming to an end. When I first saw it, I was convinced that the sailor and the nurse were reunited lovers who were expressing their happiness over the long awaited news. Their poignant uniforms evoked images of two people committed to service in a time of national need. They, more than most, deserved a moment of bliss after sacrificing so much.

It’s devastating to learn then that the iconic WWII image, which many of us associate with as a symbol of love and hope—is misleading. The truth is that on August 14, 1945, while thousands of New Yorkers spilled into Times Square to celebrate the Allies victory over Japan, a man in a sailor’s uniform confidently walked up to an unsuspecting woman and forcibly kissed her without consent. And just like that, history immortalized an image representing assault.

The real story of our sailor and nurse is one of a strange coincidence. Alfred Eisenstaedt, a photographer for Life Magazine, was on the prowl that day to capture an image that would help readers visualize not what the end of the war looked like but felt like (U.S. Naval Institute). He believed that with enough patience, he would find that image in the throws of the growing crowd of revelers gathering on New York City streets (U.S. Naval Institute). These everyday folks didn’t know what to do with themselves as news broke that Japan had agreed to concede. They poured out of buildings onto the streets of Manhattan as if to ask, “have you heard?” en masse. People were shouting, cheering, and of course, drinking. There was electricity in the air, and everyone was unsure of how to release the charge. It’s among this exciting uncertainty that Eisenstaedt caught sight of our sailor, George Mendonsa, taking determined steps in a single direction. Eisenstaedt followed to see what would happen.

On his last day of shore leave, Mendonsa and his girlfriend Rita Petry were catching an afternoon movie at Radio City Music Hall (U.S. Naval Institute). Already in uniform, he would be departing for San Francisco that night to join the crew of The USS The Sullivans (Washington Post). The news reached moviegoers when civilians started banging on the theater doors and shouting that the war was coming to an end. Everyone, Mendonsa and Petry included, left the theater mid-film to join the celebration on the streets (U.S. Naval Institute).

Our nurse is Greta Zimmer Friedman a Jewish refugee from Austria who lost both her parents in the Holocaust (Washington Post). Although she wore a nurse’s uniform, she was actually a dental assistant who worked in Manhattan. That morning, patients came in and out of the office excitedly sharing the news that the war had ended. Hopeful, Friedman took a lunch break and decided to walk towards the ticker-tape sign on Broadway near Times Square to read the news for herself (U.S. Naval Institute).

At this point, Petry and Mendonsa are leaving Childs Restaurant, where they had finished celebratory drinks (U.S. Naval Institute). As Mendonsa walks down the street slightly ahead of Petry, a white nurse’s uniform catches his eye. He remembers the front-line nurses he witnessed tending to unimaginable battle wounds and suddenly quickens his pace, enlarging the gap between him and Petry (U.S. Naval Institute). This is where Eisenstaedt began to follow. As he pursued, camera at the ready, Mendonsa made his way towards Friedman—who had turned away from Mendonsa to walk in the opposite direction. Then, without a word, Mendonsa reaches Friedman, grabs her from behind, and begins to kiss her.

“Though [Mendonsa] halted his steps just before running into [Friedman], his upper torso’s momentum swept over her. The motion’s force bent [Friedman] backward and to her right. As he overtook [Friedman]’s slender frame, his right hand cupped her slim waist. He pulled her inward toward his lean and muscular body. Her initial attempt to physically separate her person from the intruder proved a futile exertion against the dark-uniformed man’s strong hold. With her right arm pinned between their two bodies, she instinctively brought her left arm and clenched fist upward in defense” (U.S. Naval Institute).

This collision of bodies resulted in the infamous pose we know today. In many ways, it’s the pose itself, that attracted people to the image. “The struck pose created an oddly appealing mixture of brutish force, caring embrace, and awkward hesitation” (U.S. Naval Institute). When the kiss was over, the two parted, going their separate ways, neither of them acknowledging what had just happened (Veteran’s History Project). Unbeknownst to both of them, Eisenstaedt was there to capture the surreal moment. He had found his money shot.

Mendonsa is not the bad guy in this story. We honor his service to his country and are indebted for his sacrifice. Given the era and the circumstances that led to the kiss, some have argued that it was harmless, an over-excited expression of happiness—a release of the pent-up joy that Mendonsa was experiencing. Even Friedman, in a 2005 interview, stated that while she did not ask for the kiss, it was “more of a jubilant act that [Mendonsa] didn’t have to go back [to the war]” rather than something menacing (Veteran’s History Project). But in 2021, it isn’t easy to associate innocent intentions with any form of non-consensual touch.

Friedman wasn’t the only woman to receive unwanted advances that day. Over the next few days and in dozens of cities across the U.S., men were celebrating by “grabbing,” “kissing,” and “molesting” women on the streets (Washington Post). It had become a real problem.

“The Boston Globe relayed news of servicemen in Scollay Square “attacking women and girls.” In Chicago’s Loop, a 13-year-old girl who had never been kissed panicked at the sight of a sailor coming toward her. She tried to evade him in the crowd, but he caught her and took her on the mouth. The worst unrest occurred in San Francisco, where during three days of “peace riots,” rampaging sailors looted, overturned cable cars, “molested” women or stripped them of clothing and, in some cases, beat their escorts. Many allegations of sexual assault described by witnesses, including gang rape, surfaced, and in subsequent weeks city officials admitted that at least six rapes took place” (Washington Post).

Eisenstaedt’s “The Kissing Sailor” became his career’s most famous image, “Life Magazine’s most reproduced and one of history’s most popular” (U.S. Naval Institute). Today, the image remains a centerpiece of our visual history and has even inspired a 26-foot-high statue. “Unconditional Surrender” is a series of computer-generated sculptures by Seward Johnson which resemble “The Kissing Sailor.” The installation has traveled to Sarasota, Florida; San Diego, California; and New York City, among other places. American culture has embraced the image in all its well-intended glory and embedded it into our collective history.

Friedman passed away in 2016, Mendonsa in 2019. After Mendonsa’s death, the media began to re-focus on the photo’s origin story, and discussions resurfaced about the photo’s appropriateness and its glorification of sexual assault. The “Unconditional Surrender” statue in Sarasota, Florida, was spray-painted with #metoo the day after Mendonsa’s death (CNN).

Although Friedman never publicly expressed any regret or anger over her experience, I can’t help but wonder if she was simply a good sport. For me, the image feels tainted because it reinforces a “no means yes” culture. However, learning about the photo’s history was a reminder that behind the icons, stories, and narratives that we cherish is an opportunity to explore the truth. And uncovering the truth is always worth a thousand words.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.