What the Tsarnaevs Didn’t Know

The untold story of Chechen non-violence

When the Boston bombing trial dominated the media, its perpetrators, the Tsarnaev brothers, were associated with a geography scarcely known by Americans: Chechnya. If there was any examination in Chechnya’s history, rarely did it go beyond this: the bombers hailed from a Republic whose leader, Dudaev, had briefly made a bid for independence in 1992, the upshot of which was a catastrophic twenty-year-long war that decimated the local population.

When that war was launched, Dzhokhar (pronounced “Johar”) Tsarnaev was merely two years old. He was born in Kazakhstan, where his family had been forcibly relocated in 1944. This deportation, ordered by Joseph Stalin, was directed against every single Chechen living in Chechnya at that time. All were deported, without exception, and many Chechens died along the way while America, Great Britain, and France embraced the Soviet Union as an ally in their fight against the Third Reich.

The 1944 deportation is only one of the many important details that have been left out of most English-language coverage of Chechnya’s recent history in connection with the Boston bombings. Just as important are the many alternatives to terrorism that were cultivated among Chechens from the early decades of the nineteenth century, and which continue to carry significant weight among Chechens today.

The History of Chechen Nonviolence

While the media has waxed verbose concerning the Tsarnaevs’ terrorist tendencies, television programs and newspapers have remained conspicuously silent concerning the longer history of Chechen nonviolent resistance to imperial rule. While violence is the dominant image with which Chechnya is associated today, as in other colonial situations, Chechen violence has more to do with the Russian state that colonized it than with Chechen culture.

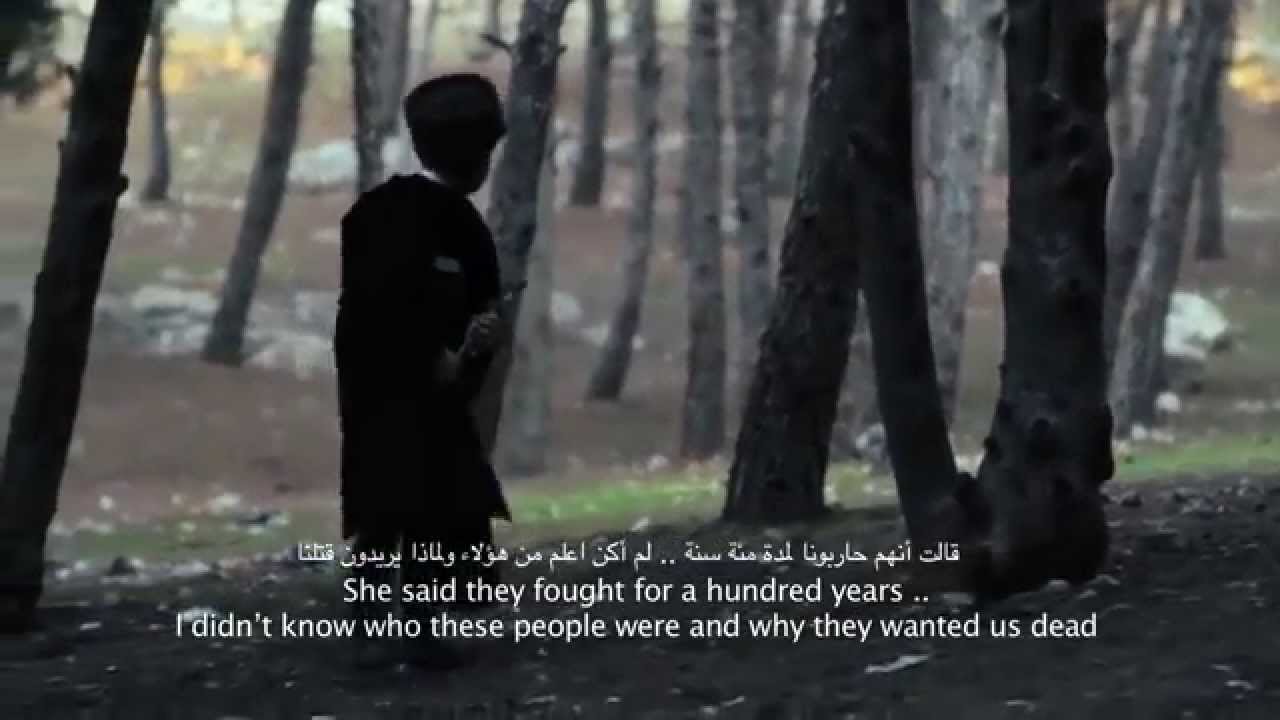

My book, Writers and Rebels: The Literature of Anticolonial Insurgency in the Caucasus (published by Yale University Press in 2016), showcases the diversity of Chechen forms of resistance to the colonial state that starkly contrast with the representations of Chechen violence that dominate the media. Many of these forms of unarmed resistance were associated with a strand of Islam that is all too frequently erased from contemporary analysis: Qadiriyya Sufism, named for the twelfth-century mystic Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani of Baghdad. It was from the Qadiris that Chechens learned to practice the devotional prayer called the zikr (Arabic for “remembrance”), as seen in this video:

Among the most important of al-Jilani’s modern disciples was Kunta Hajji (b. 1830), who was also one of the most influential proponents of non-violence among Chechens. A Turkic shepherd who grew up in a Chechen milieu, Kunta Haji traveled from Baghdad back to Chechnya, spreading the teachings of nonviolence to his Chechen followers. His followers only became radicalized in the late 1860s, after their leader was violently arrested by Russian troops. Kunta Hajji was banished to the outer limits of the Russian empire for promoting his unorthodox version of peace.

Prior to this violence, Kunta Haji’s disciples had been vigorously apolitical and eager to accommodate the Russian state. The state’s violent suppression of Kunta Hajji radicalized his followers and marked a turning point in local forms of resistance. After that, Chechens responded with armed militancy and a surge in banditry, that extended to the killing of the same officer class that had actively exterminated the Chechen population. Notwithstanding its temporary radicalization towards the end of the nineteenth century, Kunta Hajji’s pacifism continues to have a substantial legacy in contemporary Chechnya and surrounding regions.

Unsurprisingly, the Boston bombing was followed by a sudden upsurge in media interest in Chechnya. The attempt to link this act to the violence in Chechnya is misguided in many respects. Having moved to the US in their childhood, both Tsarnaevs were products of US culture. Their romanticization of violence was American, in line with the video games they consumed, the violent movies they watched, and the consumerist culture in which they came of age.

The real lesson that comes from thinking of Chechnya in connection with the Boston bombing is in seeing what the Tsarnaev’s didn’t see and didn’t know. Had Jahar studied his people’s past, he would have read about Kunta Hajji, who taught his followers to perform the Sufi zikr, which involves reciting the name of God repeatedly, loudly, and with passion when they were oppressed, rather than mimicking colonial violence. He would have come across the Pankisi Gorge, on the border between Chechnya and Georgia, where Christianity and Islam are practiced side by side to this day, and where Muslims and Christians are buried in the same cemeteries. While Pankisi has long been labeled a bastion of terrorism by the state department, it would more accurately be described as a bastion of peace.

Jahar would have read of Soviet-era Chechen Sufi sheykhs, such as Batal-Hajji and Bammat Girey Hajji, who saw themselves as followers of the pacifist teachings of Kunta Hajji, and who nonviolently resisted the atheist state by continuing to live as Muslims. Jahar would have learned of the special status in Chechnya accorded to Tolstoy, who, although Russian, is revered from Grozny to Vedeno for his sympathetic rendering of Chechen woes in the novella Hadji Murad (1912). He would have learned to complicate his vision of an eternally aggressive Russian regime with deeper historical knowledge of Chechens’ creative ways of living with and within oppressive rule. Had the Tsarnaevs not conceived of the Chechens as helpless victims, it is less likely that they would have become aggressors.

Many resources are available for those wishing to learn more about Chechen nonviolence (see below for a few). Chechen narratives of peace can counter the American romance with terrorist violence. We can learn from Islamic teachings that condemn the massacre of innocents, including those that originated in the Caucasus. We can — and indeed must — make apparent in this age of terror and Islamophobia what Kunta Hajji never forgot: the literal meaning of the word Islam, the religion of peace.

Further Resources

Julietta Meskhidze, “Shaykh Batal Hajji from Surkhokhi: towards the history of Islam in Ingushetia,” Central Asian Survey 1- 2 (2006): 179–191.

Moshe Gammer, Muslim Resistance to the Tsar: Shamil and the Conquest of Chechnia and Dagestan. London: Taylor & Francis, 1994.

Rebecca Ruth Gould, “Secularism and Belief in Georgia’s Pankisi Gorge,” Journal of Islamic Studies 22.3 (2011): 339–373.

Amjad Jaimoukha, The Chechens: A Handbook. New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2005.

This story first appeared on Medium.

About the Creator

Rebecca Ruth Gould

I am author of the award-winning book Writers and Rebels: The Literature of Insurgency in the Caucasus (Yale University Press, 2016). My Wikipedia page.

Subscribe to my YouTube Channel Poetry & Protest. ⬆️

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.