Introduction

Title and reputation are very important. This is as true today as it was during the 14th century. Alexander Stewart, who is also referred to as the ‘Wolf of Badenoch’, was responsible for a great many actions, some of them classed as truly horrific and had a huge impact on Highland culture and society. But does Alexander Stewart of Buchan deserve his epithet as the ‘Wolf of Badenoch’? Or was he following the orders that he was given to uphold peace in the Highlands to the best of his ability? It is believed that the findings within this essay will show that Alexander Stewart did deserve his epithet due to a combination of factors and not just one.

Title, Distinction and Lineage

As his epithet suggests Alexander Stewart’s first title and primary responsibility was that of the Lord of Badenoch, based in the Grampians. It was his father’s for much of the 1360s with Alexander Stewart taking the position on the 30th March 1371. The position of Badenoch was part of an attempt to bring order to the Highlands.[1] Alexander Stewart held many titles during his career; he was the King’s lieutenant, Lord of Badenoch and Earl of Buchan, which he received, in part, due to his marriage to the countess of Ross.[2] He also received the title and position of justiciar or chief justice for the north of Scotland but lost this title in November 1388.[3] But his most famous title was that of the “Wolf of Badenoch” which was in some part due to his heraldic crest which was a wolf, however in others it was due to his reputation of being incredibly ruthless.[4] It could also have been a combination of factors that may have earned him the title while Sir John Keltie suggests that the ferocity of his personality may have been enough.[5]

In 1362, when Alexander Bur was appointed Bishop of Moray based out of Elgin Cathedral, Bur in an effort to keep the Stewart royal family on side and to help keep the peace in the Highlands, signed an agreement with Alexander Stewart that the estates belonging to the Bishop were now put under his protection.[6]

Destruction across Moray

However, after the crowning of Robert II in 1371 the relationship between Bur and Stewart broke down and, in an effort to improve the situation, Bur allied himself with Alexander Stewart’s brother, Robert, who took control of the situation.[7] On the 11 December 1388 Alexander Stewart was removed from his position and the office of justiciar after it was agreed by the council that he: ‘was accused at various other times before the king and council of being negligent in the execution of his office’. It was then the view of the council to remove Alexander Stewart and replace him with another suitable person.[8]

After his ex-communication in May 1390, Alexander Stewart started his vengeful campaign with the burning and destruction of the town of Forres. This included the church which reportedly still had inside the local choir.[9] From Forres Alexander Stewart and his forces continued and on 17 June 1390 arrived in Elgin and burnt down the cathedral along with the residences.[10] The forces that were used to assist him in his rampage across Moray were, as quoted by Stewart himself, the “wild, wikkid hielandmen”.[11] This brief statement from Alexander Stewart gives way to the opinion of Highland men during this time. The words “wild” and “wikkid” suggest that the Highland people were an uncivilised society and, although this may have been bravado in an attempt to impress the family back home, it was a popular opinion of Highland culture during this time.[12] In August 1390 Alexander Stewart’s brother, now King Robert III ordered that Alexander:

“not to interfere in any part with the castle of Spynie by further pretext”[13]

There is no record, unfortunately, if Alexander Stewart acknowledged the King’s request but Spynie Palace was left unharmed.[14] Although there is some evidence that Alexander Stewart did obey the order to leave Spynie, the nearby Abbey of Pluscarden was not so fortunate. Prior to the burning of Elgin Cathedral, Stewart’s forces pillaged the local Benedictine Abbey and caused significant fire damage to some of the building.[15]

Politics, Society and Culture

Alexander Stewart’s interference in local clan politics across Moray is an example of when Royal family feuds can overspill causing issues across much of Scotland. Stewart’s feud was not confined to Forres or Elgin and also instigated cattle raids across much of the area of Moray and had a part to play on raids in Angus and the battle in 1396 against Perth.[16] The Highland Gaelic people, sometimes referred to as caterans, were, as highlighted previously, thought of as quite savage individuals and despite legislation would often take part in cattle raids throughout the region. The legislation was highlighted in the council meeting in November 1384 and said:

‘It is also decreed and ordained that no one shall travel through the country in any part of the kingdom in the manner of a cateran.’[17]

The legislation further more stated that if any cateran were to break this law they would be treated as if they were an exile. This treats the caterans as if they were part of a sub-society within Scottish culture, one that appears Alexander Stewart used to his advantage.[18]

Though these people were often looked down on and frowned upon they could often be seen as being quite useful to the upper class to strengthen their military presence and improve their profile. From the evidence provided so far within this essay, it is clear that this would appear to be the case with Alexander Stewart.[19] Moray as an area within Northern Scotland was a place in constant conflict and dispute. As a result churchmen and town inhabitants would often complain about the ongoing raids, Alexander Stewart appeared to take advantage of this situation and use the caterans for his own means in burning down Forres and Elgin.[20]

The actions of the “Wolf of Badenoch” were severely criticised by the general council in Scotland in 1385 This would suggest how the unauthorised actions of one man were severely frowned upon by the rest of his kin.[21] It was not just his continuing aggressive actions that were coming under question, Alexander Stewart had become one of the most powerful land owners in Scotland either through marriage or title. With land did indeed come power but in 1385 Alexander Stewart failed to pay the lease owed to his half-brother David on Urquhart making the situation worse, showing in turn a certain amount of arrogance.[22] In further response Alexander Stewart was prosecuted and ordered to make recompense to the Bishop of Moray and also to obtain absolution from the Pope. He agreed to all of this in the presence of his brother King Robert III and the other nobility at Blackfriar’s church in the city of Perth.[23] It is reported that when he appeared before his brother, the King, and the other nobles that he appeared as part of his penance dressed in a sack cloth and on his bare knees seeking forgiveness. Although his reputation up until this point has been that of a ruthless individual, this in part shows that Alexander Stewart recognised authority and tradition.[24] Part of his penance and repayment to the Bishop of Moray was that he also had to help rebuild and repair the Cathedral at Elgin that he originally had burnt down, Though there is no record if he had to do the same for the town of Forres.[25] Michael Lynch in his book Scotland: A New History believes that Alexander Stewart’s twenty-year campaign across the Highlands of Scotland was not something that was unique to one member of the Stewart Royal family.[26] It was indicative of the whole family, a trait that shows how far one family in Scotland is willing to go to get what they want, a feud that started within the Royal family and that disrupted much of the Highlands and its people.[27]

A Reputation throughout History

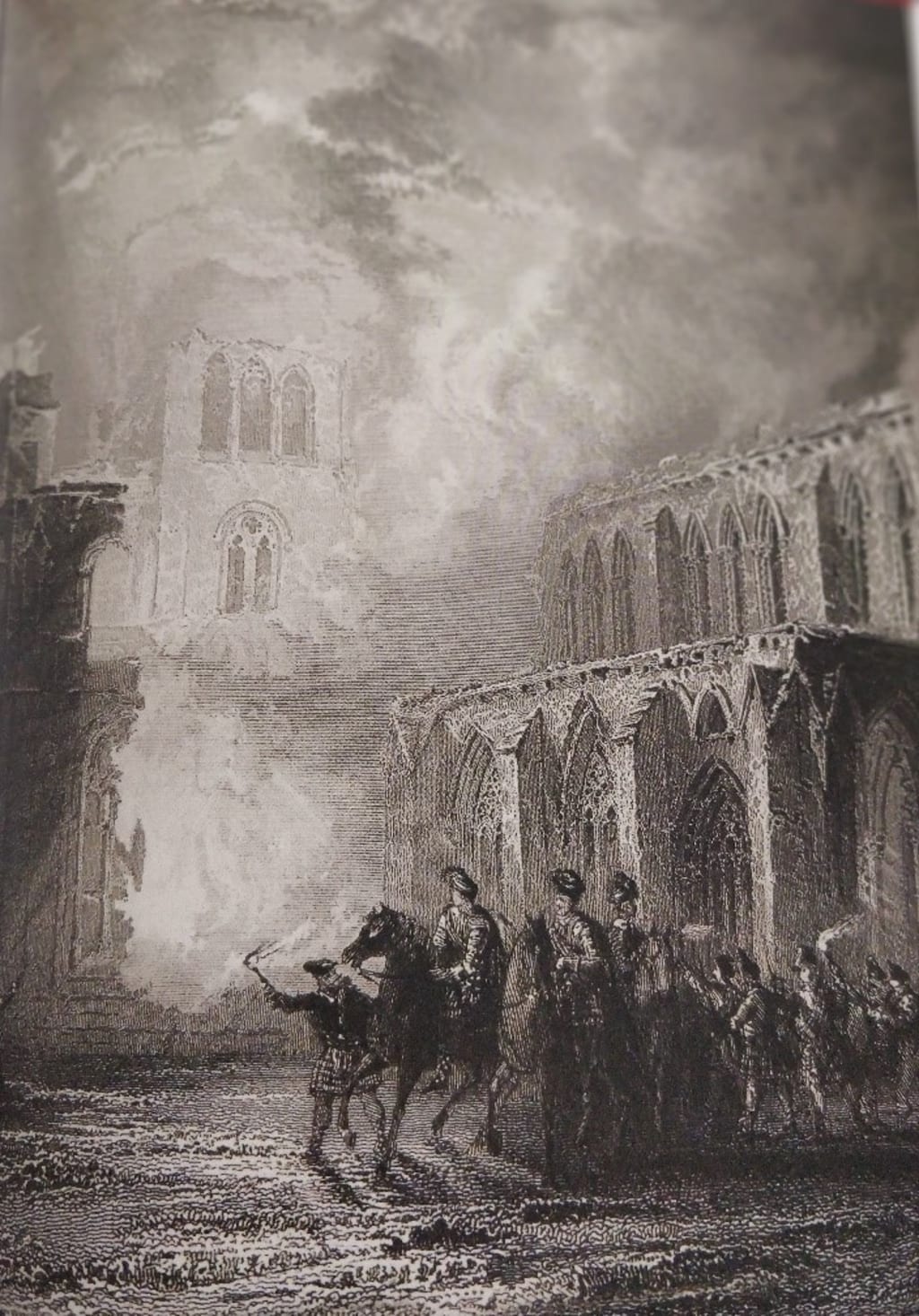

The reputation of the ‘Wolf of Badenoch’ has continued much into the years that followed with the Scotsman newspaper describing him as ‘Scotland’s vilest man.’[28] His rampage across Moray and his bad tempered persona has been used in fictional writings, for example such as ‘Island of the Swans’ by Ciji Ware. In this Alexander Stewart has been described as “...where the devil himself would retreat after doin' his evil across the countryside”.[29] But despite his ruthless reputation his presence within Scottish history especially within the city of Elgin is still remembered with a statue of Alexander Stewart being unveiled back in 2016 but with the artist stating: "It’s been really interesting. I have also really enjoyed doing his face and making him look nasty." Despite historical remembrance Alexander Stewart’s ruthless demeaner is his main feature.[30] The destruction of Elgin cathedral has also been recreated as shown in figure 1 below. Depicted by Thomas Allan in 1842 it clearly shows the type and the level of destruction that might have occurred.[31]

See Figure 1 above - Destruction of Elgin Cathedral by Thomas Allan, 1842.[32]

The Aftermath

After his ex-communication and penance Alexander Stewart spent less time in the Northern Highlands and focused his efforts south, specifically in the area of Perth. He died in the same area on 20th June 1405 and was buried in Dunkeld Cathedral.[33] Though his destruction and rampage across Moray caused much damage and death his primary responsibility to bring order to the Highlands had a certain amount of success. Using the caterans as his forces, there were less raids across Northern Scotland and the fear of the ‘Wolf of Badenoch’ was distilled into the people of the Highlands. Clan warfare and disruption increased within the region, especially in the area of Inverness and was later resolved by Sir David Lindsay and the Earl of Moray.[34] The resolution was an arranged battle between two clans who each had to pick thirty men to take part. The battle itself was in Perth and happened in 1396.[35]

Conclusion

In conclusion this essay has shown examples where Alexander Stewart does deserve his epithet of the ‘Wolf of Badenoch,’ linked in a small part due to the wolf on his coat of arms. Additional proof has been shown through his actions in the Highlands, for example the destruction of property in both Elgin and Forres where many lives would have been lost. There were also instances where Alexander Stewart would abuse his power using caterans or Highland people to perform raids across much of Moray and beyond. This added to an already unpleasant view of Highland people. The history books have not been the only proof in answering this question. Records from the Scottish government have also shown the disapproval from council meetings of Alexander Stewart’s actions and how he must be punished. As noted at the start of this essay, titles and reputations have a huge impact on society and the ‘Wolf of Badenoch’ has been noted in Scottish history as being one of the most ruthless individuals up until the present era, despite any order he might of brought to the Highlands.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Brown, K.M, ed., The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 - 1384/11/1 (St

Andrews, 2007) <https://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1384/11/10> [accessed 6 April 2020].

———, ed., The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 - 1388/12/3 (St Andrews, 2007) <http://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1388/12/3> [accessed 6 April 2020].

Secondary Sources

Bleach, Lorna, and Keira Borrill, Battle and Bloodshed: The Medieval World at War (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014).

Brown, K.M, ed., The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 - 1384/11/1 (St

Andrews, 2007) <https://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1384/11/10> [accessed 6 April 2020].

———, ed., The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 - 1388/12/3 (St Andrews, 2007) <http://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1388/12/3> [accessed 6 April 2020].

Cannon, John, and Anne Hargreaves, ‘Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan’, in The Kings and Queens of Britain (Oxford University Press, 2009) <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199559220.001.0001/acref-9780199559220-e-402> [accessed 30 March 2020].

‘David Prepares Wolf Sculpture for Elgin Unveiling’, Northern Scot, 2016 <https://www.northern-scot.co.uk/news/david-prepares-wolf-sculpture-for-elgin-unveiling-145899/> [accessed 10 April 2020].

Grant, Alexander, Stewart, Alexander [Called the Wolf of Badenoch], First Earl of Buchan (c. 1345–1405), Magnate (Oxford University Press, 2005) <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-26451>.

Keltie, Sir John Scott, A History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments: With an Account of the Gaelic Language, Literature, and Music (A. Fullarton, 1875).

Lynch, Michael, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1995).

Lyon, Charles Jobson, History of St. Andrews: Episcopal, Monastic, Academic, and Civil, Comprising the Principal Part of the Ecclesiastical History of Scotland, from the Earliest Age Till the Present Time (W. Tait, 1843).

Owen, Dr Kirsty, Elgin Cathedral: Official Souvenir Guide (Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland, 2017).

Panton, James, Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy (Scarecrow Press, 2011).

Sellar, W. D. H., and Michael Brown, ‘Moray’, in The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford University Press, 2001) <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199234820.001.0001/acref-9780199234820-e-209> [accessed 30 March 2020].

Tabraham, Chris, Spynie Palace: Official Souvenir Guide (Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland, 2019).

‘The Wolf of Badenoch - Scotland’s Vilest Man?’ <https://www.scotsman.com/whats-on/arts-and-entertainment/wolf-badenoch-scotlands-vilest-man-647369> [accessed 9 April 2020].

Ware, Ciji, Island of the Swans (Sourcebooks, Inc., 2010).

Footnotes

[1] Alexander Grant, Stewart, Alexander [Called the Wolf of Badenoch], First Earl of Buchan (c. 1345–1405), Magnate (Oxford University Press, 2005) <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-26451>.

[2] John Cannon and Anne Hargreaves, ‘Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan’, in The Kings and Queens of Britain (Oxford University Press, 2009) <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199559220.001.0001/acref-9780199559220-e-402> [accessed 30 March 2020].

[3] Grant, Stewart, Alexander [Called the Wolf of Badenoch], First Earl of Buchan (c. 1345–1405), Magnate.

[4] Dr Kirsty Owen, Elgin Cathedral: Official Souvenir Guide (Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland, 2017), 36.

[5] Sir John Scott Keltie, A History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments: With an Account of the Gaelic Language, Literature, and Music (A. Fullarton, 1875), 68.

[6] Owen, Elgin Cathedral: Official Souvenir Guide, 36.

[7] Owen, Elgin Cathedral: Official Souvenir Guide, 36.

[8] The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 - 1388/12/3, ed. K.M Brown (St Andrews, 2007) <http://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1388/12/3> [accessed 6 April 2020].

[9] Keltie, A History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments, 68.

[10] Owen, Elgin Cathedral: Official Souvenir Guide, 36.

[11] Owen, Elgin Cathedral: Official Souvenir Guide, 36.

[12] Michael Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1995), 68.

[13] Owen, Elgin Cathedral: Official Souvenir Guide, 36.

[14] Chris Tabraham, Spynie Palace: Official Souvenir Guide (Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland, 2019), 19.

[15] James Panton, Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy (Scarecrow Press, 2011), 439.

[16] Lynch, Scotland: A New History, 68.

[17] The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 - 1384/11/1, ed. K.M Brown (St Andrews, 2007) <https://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1384/11/10> [accessed 6 April 2020].

[18] Brown, The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 - 1384/11/1.

[19] Lorna Bleach and Keira Borrill, Battle and Bloodshed: The Medieval World at War (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014), 98.

[20] W. D. H. Sellar and Michael Brown, ‘Moray’, in The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford University Press, 2001) <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199234820.001.0001/acref-9780199234820-e-209> [accessed 30 March 2020].

[21] Lynch, Scotland: A New History, 139.

[22] Grant, Stewart, Alexander [Called the Wolf of Badenoch], First Earl of Buchan (c. 1345–1405), Magnate.

[23] Lynch, Scotland: A New History, 68.

[24] Charles Jobson Lyon, History of St. Andrews: Episcopal, Monastic, Academic, and Civil, Comprising the Principal Part of the Ecclesiastical History of Scotland, from the Earliest Age Till the Present Time (W. Tait, 1843), 186.

[25] Cannon and Hargreaves, ‘Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan’.

[26] Lynch, Scotland: A New History, 68–69.

[27] Lynch, Scotland: A New History, 68–69.

[28] ‘The Wolf of Badenoch - Scotland’s Vilest Man?’ <https://www.scotsman.com/whats-on/arts-and-entertainment/wolf-badenoch-scotlands-vilest-man-647369> [accessed 9 April 2020].

[29] Ciji Ware, Island of the Swans (Sourcebooks, Inc., 2010), 212.

[30] ‘David Prepares Wolf Sculpture for Elgin Unveiling’, Northern Scot, 2016 <https://www.northern-scot.co.uk/news/david-prepares-wolf-sculpture-for-elgin-unveiling-145899/> [accessed 10 April 2020].

[31] Owen, Elgin Cathedral: Official Souvenir Guide, 37.

[32] Owen, Elgin Cathedral: Official Souvenir Guide, 37.

[33] Grant, Stewart, Alexander [Called the Wolf of Badenoch], First Earl of Buchan (c. 1345–1405), Magnate.

[34] Grant, Stewart, Alexander [Called the Wolf of Badenoch], First Earl of Buchan (c. 1345–1405), Magnate.

[35] Grant, Stewart, Alexander [Called the Wolf of Badenoch], First Earl of Buchan (c. 1345–1405), Magnate.

About the Creator

David Harrison

Hi everyone I am a writer based in the Highlands of Scotland in the city of Inverness, I have a degree in Scottish History and Theology and use some of this knowledge as a basis for some of my writing. I hope you enjoy what I publish.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.