Submarines: Air-Independent Propulsion

Longer, quieter underwater duration than diesel-electric and without nuclear complications

I wrote recently about Russia launching Kalibr missiles from its Varshavianka (Improved Kilo) class submarines in the Black Sea. That set me off to explore the latest submarine technology and Air-Independent Propulsion, although not new as such, is certainly leading the way in the non-nuclear fleets. And in some countries with nuclear fleets too. Here’s what I discovered.

Endurance is an issue

Nuclear submarines are said to have ‘unlimited’ underwater endurance, but we know that’s not accurate. They may have unlimited power, perhaps for many years without reactor refuelling (the UK Astute class is designed for 25 years), power which can be used to make fresh water (the critical resource for any mariner) and generate oxygen from seawater.

But mariners need food too. As far as I know, nuclear submarines cannot grow food — hydroponic systems are not yet that far advanced, although they may carry dehydrated food. And I don’t think they do too much fishing either. The amount of food a nuclear submarine carries is probably classified information.

And mariners die.

There is no ‘breeding’ on nuclear submarines (as far as I know). Nuclear submarines are not like the Starship Enterprise. I’m not really a Trekkie so I don’t know whether they bred in space, although I can’t remember ever seeing a kids or a creche in an episode. And talking of breeding, there are no breeder reactors on nuclear submarines.

Therefore, all submarines have to be replenished at some point in time and space (at sea or in a dock but not in orbit, obviously). Consumables such as lub oil can’t be manufactured aboard (for equipment use, not for the crew to consume).

Submerged time

It’s all down to submerged time, stealth and propulsion system — and they are all inter-related. By propulsion system I mean, essentially, power plant through a conventional propeller (screw). I’m not going into the less common power transfer methods such as pump-jet that ‘put the rubber on the road’. Then there’s the caterpillar drive, if they really yet exist — remember Tom Clancy’s Red October?

Without question, nuclear power gives the longest underwater duration — typically 3 month patrols in peacetime— and these boats are the most technically complex and therefore cost the most. Few navies have them: the US, UK, France, Russia, China and India, but more than twenty countries operate AIP submarines.

Pure electric power gives the shortest duration (typically a days or two under power). These tend to be highly specialised, such as midget submarines for specific mission profiles. These are the most stealthy across a mission.

Diesel-electric power is by far the most common type. These boats are the cheapest (excluding midgets) and almost all navies have them. The technology has been around for over a hundred years. Some are the most stealthy — at times. They have to access air (oxygen) for their air breathing diesels to recharge their batteries, and when they do that — even using a snorkel close to the surface — they are vulnerable to detection and attack.

The ratio between this time of greater vulnerability and the total operating time is known as the ‘indiscretion ratio’ and for all conventional modern submarines, the indiscretion ratio ranges typically from 7% to 10% on patrol at 4 knots, and 20% to 30% in transit at 8 knots.

That’s why air-independent propulsion systems have attracted so much interest — the indiscretion rate. Like getting caught with the neighbour’s wife and your pants down.

New battery and fuel-cell technologies are changing the game for non-nuclear boats. But, strangely, it’s old, cheap and relatively forgotten technology that has demonstrated success — the Stirling engine.

What is Air Independent Propulsion (AIP)?

Air independent propulsion (AIP) is a set of technologies that allow submarines to operate without the need to surface or use snorkels to access atmospheric oxygen. AIP can supplement or replace the submarine’s diesel-electric propulsion system, providing a quieter and more stealthy vessel.

Most such systems generate electricity, which in turn drives an electric motor for propulsion or recharges the boat’s batteries.

Modern non-nuclear submarines are potentially stealthier than nuclear submarines. Some of the latest nuclear submarine reactors are designed to rely on natural reactor coolant circulation but most naval nuclear reactors use pumps to continuously circulate the reactor coolant and pumps generate some amount of detectable noise.

Types of AIP system

There are several different types of AIP systems currently in use, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The three main types are:

1. Closed cycle steam turbines

Take a nuclear sub without the nuclear. Mix oxygen and ethanol to produce heat and make steam to drive a turbine. This system — the French call it MESMA — is complex. It is powerful but less efficient than the alternatives. And, we’re back to oxygen, but it’s liquid oxygen.

2. Fuel cells

Fuel cells, are very quiet but require highly purified hydrogen fuel, which can be difficult to store and transport. This system is used in addition to conventional diesel-electric power, offering much greater operational flexibility.

Thyssen-Krupp Marine Systems have developed a world-leading fuel cell technology portfolio (‘HDW’) for AIP submarines which they build and licence to other builders.

Stirling Cycle

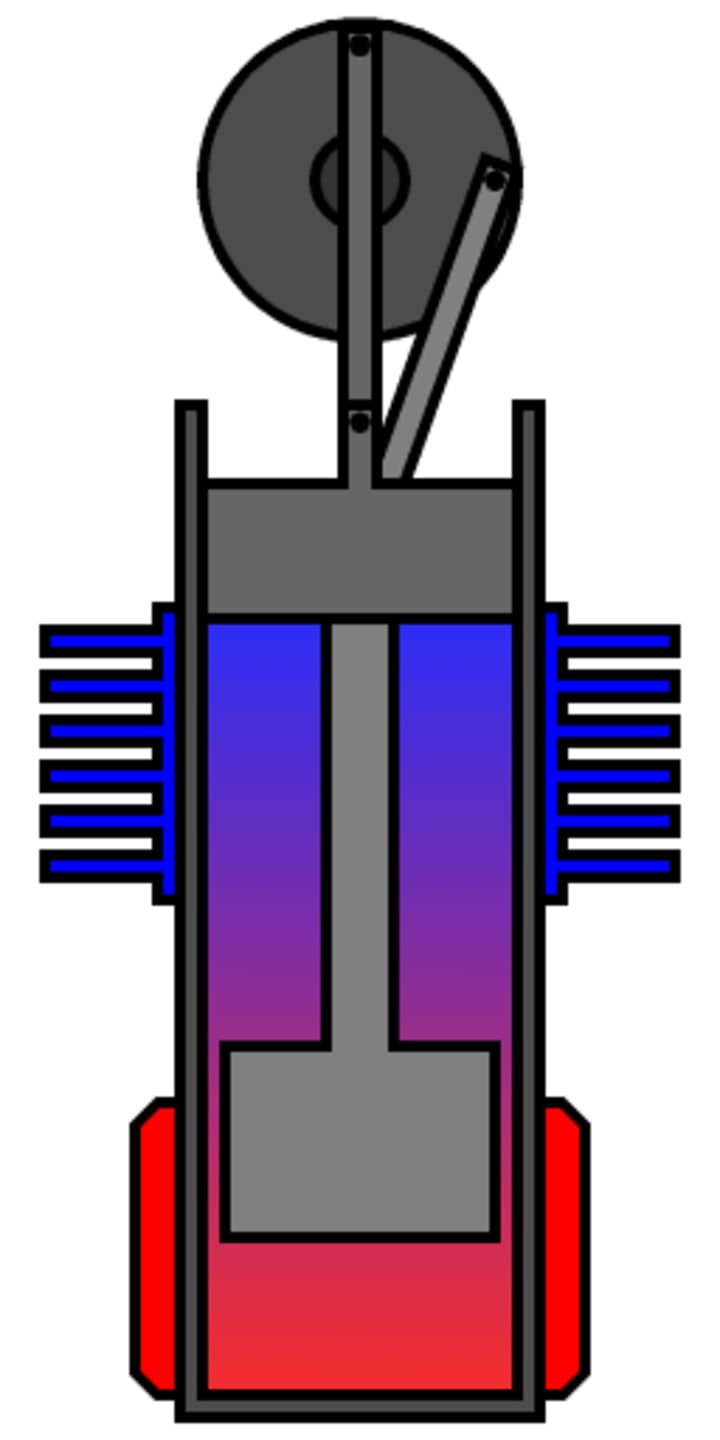

A Stirling cycle engine uses diesel to heat a fluid permanently contained in the engine, which in turn drives a piston and generates electricity which charges batteries and drives an electric motor. This is slightly more efficient and less complicated than the French MESMA, and is used on Japanese (Sōryū class), Swedish (Gotland and A26 classes) and Chinese boats.

The Japanese Sōryū class boats each use four Kockums Stirling engines built by Kawasaki under licence. These boats are being widely exported. They also have conventional diesel engines for surface transit. Notably, the latest in the class is being equipped with Lithium Ion batteries.

The main feature of the Kockums Stirling engine is the burning of pure oxygen and diesel fuel in a pressurized combustion chamber. The combustion pressure is higher that the surrounding sea water pressure, thereby allowing the exhaust products, dissolved in seawater, to be discharged overboard without using a compressor. Oxygen is stored in liquid form (LOX) in cryogenic tanks.

Simply, the Stirling engine is a type of external combustion engine that uses a piston to circulate a working fluid (usually air) between two heat exchangers. The hot side of the heat exchanger is heated by an external source, such as a burner (LOX and diesel fuel), while the cold side is cooled by the surrounding environment (sea water used as coolant).

Unquestionably, a Stirling engine set up will be noisier than fuel cell driven submarines, but much quieter than diesel-engined submarines near the surface — diesel engines have valve clatter and other mechanical noise which not present in Stirling engines when charging batteries. How much of that noise escapes the submarine is obviously a key issue which I’m not going to delve into here — but it is very small — and I’ll cover it in another story.

Notes

Closed-cycle diesel electric submarines are obsolete.

AIP systems can be retrofitted to existing submarines.

What are the benefits of AIP?

AIP provides a number of advantages over traditional diesel-electric propulsion, most notably increased submerged endurance and reduced noise signatures. These factors make AIP-powered submarines more difficult to detect and track, giving them a strategic advantage in potential conflict situations.

The Swedish Gotland submarines are believed to have an endurance of 2 weeks (depending on mission profile) without surfacing.

What are the challenges of AIP on submarines?

One of the biggest challenges facing AIP fuel cell technology is the need for expensive and difficult-to-obtain hydrogen fuel.

The Stirling engine on submarines requires liquid oxygen and diesel fuel. Liquid oxygen has to be stored in a cryogenic tank.

Stirling power appears to be winning this race, but as is so often the case, the French are going their own way with MESMA and the Scorpene class.

Which countries have AIP submarines?

Several countries have developed and deployed AIP-powered submarines, including China (Yuan-039 class), Egypt (209), France (Agosta 90B, Scorpène and Kalvari classes), Germany & Norway (212CD), Greece (Type 212 and 214), Israel (Dolphin class, a 212 derivative), Italy (Tornado), Japan (Soryu), Russia (likely but unconfirmed Lada class), South Korea (Dosan Ahn Changho class), Spain (S80), Sweden (Gotland and A26 classes), Turkey (214).

Submarines designated classes 209, 212, 214, 218 use Thyssen-Krupp fuel cell technology.

France has exported many Scorpene/Kalvari boats to Malyasia, Brazil, India and Chile.

Chin has just commissioned a new 039D (Yuan) class boat:

The Type 039A is China’s first conventional submarine equipped with air-independent propulsion and was designed mainly as an anti-ship cruise missile platform that can stay submerged for longer in difficult-to-access shallow coastal areas. — SCMP

Neither the United States nor the United Kingdom use or build AIP or diesel electric submarines— it’s nuclear only for them.

It’s an interesting — but unrelated — fact that North Korea maintains one of the largest submarine fleets in the world, estimated at between 64 and 86 submarines.

However, there are reports that North Korea has developed an AIP system which gives 4 weeks underwater endurance.

More on Stirling engines

If you’re interested in Stirling engines, this video provides a reasonable explanation. I have no association with them.

Stirling engines have some drawbacks (which is why we don’t see them in cars), but they are well suited for use in submarines and have been proven against US carrier battle groups in war games.

And yes, a Swedish Gotland sub really did get through the USS Roanld Reagan's screen, and took photographs to prove it.

***

Canonical link: This story was first published in Medium on 6 August 2022 [edited]

About the Creator

James Marinero

I live on a boat and write as I sail slowly around the world. Follow me for a varied story diet: true stories, humor, tech, AI, travel, geopolitics and more. I also write techno thrillers, with six to my name. More of my stories on Medium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.