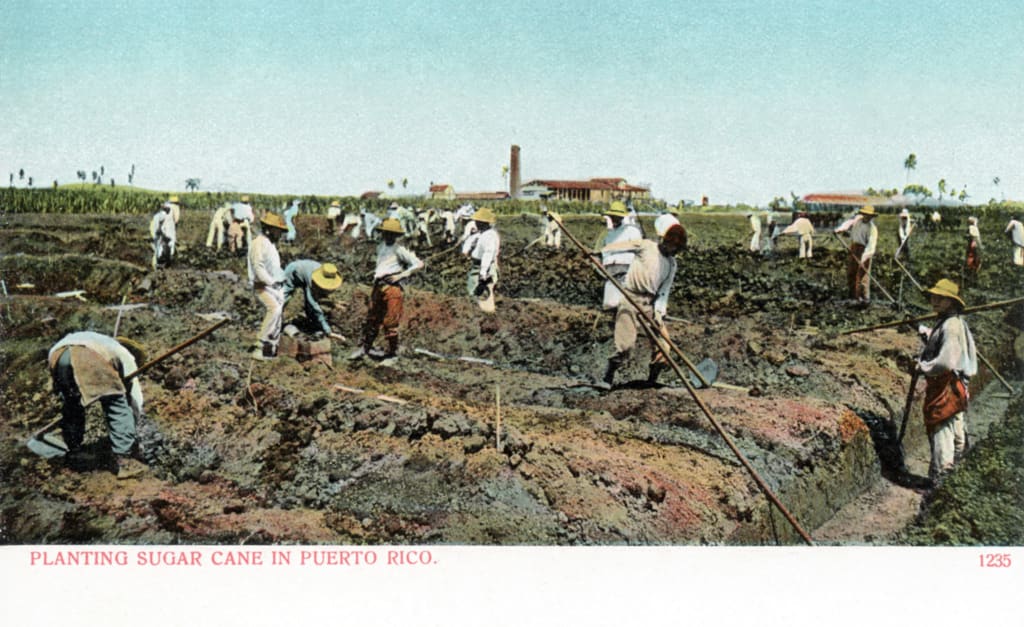

January 20th (San Juan, Puerto Rico) – Since the time of Christopher Columbus, the island-territory now known as Puerto Rico has never been independent and free. For hundreds of years, it remained a Spanish colony until the United States “liberated” it in 1898. After that, it endured as a territory of the United States federal government despite multiple attempts to change the status quo in any number of ways. Yet, perhaps it is different this time and Puerto Rico really will finally become a State, or sail off as its own sovereign nation.

During the Inauguration Ceremony, the new President surprised the world by suddenly presenting ten new Executive Orders. The eighth of these concerned the territories of the United States and specifically how having them not be fully integrated into the country goes against the ideals of the nation. Said the President:

The whole thesis of America is that the people shall not be governed without representation. Yet this is exactly what happens with our territories! Millions of individuals have no voting power in Congress and, until my election, have had no hand in selecting the President, which in turn means they have had no say in selecting federal judges. And these same judges have determined that only “some” parts of the Constitution apply to them. How can we even talk about extending freedom to the rest of the world when we cannot even do it at home?

Within the United States, there are five territories that have permanent populations: Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands. On top of these is the District of Columbia, which is strictly speaking not a territory—it is considered a “federal district”—but is treated very much the same. Beyond all of that are another 11 uninhabited islands, though many are in the general vicinity of other American States or possessions. Altogether, there are, according to the Census Bureau, over 4.3 million people spread out among these locales, most notably in Puerto Rico with 3.3 million citizens alone.

While with the prior Executive Order the President had tried to entice the rest of the world into joining the United States as new members, with this one the President attempted to induce a final decision on the fate of all of the existing American possessions. By the text of the order, in two years during the November general elections, each of the territories must put a set of questions on the ballot. Those questions were laid out as:

- Should this land and its people remain a part of the United States?

- If this land and its people remain a part of the United States, should it ascend to Statehood?

- If this land and its people ascend to Statehood, should they become an independent State, join with other territories to become a State, or join an existing State?

Based upon this, a territory could decide in the first question whether they wanted to be an independent nation or remain a part of the United States. Then, if the majority voted to remain in the U.S., the second question would determine whether they would preserve their present circumstances as a territory or become a full State with all the rights, responsibilities, and taxes that includes. This is important in that even if a person voted against staying in the United States, their opinion would still count on what to do in case their will were overridden by the majority. Finally, the last question throws a bigger wrench into the works by asking about potential ways of becoming a State: either going it alone, joining with other territories, or being a part of another current State.

This is not the first time something like this has been attempted. In 2012, a similar approach was taken in Puerto Rico, albeit in two steps. Initially in August 54% of the people voted to change the current relationship with the United States. Then in November, over 61% voted for Statehood while the remainder either voted for full independence or a “free association” that equated to a mostly independent nation, but with access to American resources and giving the United States government unfettered admission for other activities, mostly military in nature. Despite the result, Congress failed to take any action and Puerto Rico remained a territory.

More recently, on the 2020 ballot a single question was asked whether Puerto Rico should become a State. This time the results were much more subdued, with only 52% voting in favor. However, Puerto Rico once again remained a territory because Congress refused to move on these resolutions. According to the Constitution (Article 4 § Section 3 § Clauses 1 and 2), only Congress has the ability to decide the rules for the territories, in addition to the power to admit new States into the Union. As such, Congress has the sole say on the future of these lands.

Which is why it was a surprise that the Executive Order contained language that attempts to compel Congress to undertake action. In it, the President said that Congress must vote on the desires of the people and, should they want it, grant them their Statehood or independence within one year after the election. It is unclear from what statute the President is claiming the authority to take this step and it is highly likely that Congress may just ignore the Executive Branch. Past experience shows that the Supreme Court will generally stay out of “political” decisions between the other branches and will let them sort it out on their own. Given the acrimony already shown by Congress towards the independent President, it seems even more likely they will just disregard the order in its entirety, no matter the outcome of the vote.

But should ascension to becoming a State be the desire of the people, that previously listed third question brings up a myriad of possibilities. Take for instance Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. The island chains are very close in terms of a relatively empty Pacific Ocean and may decide that together—with a population of over 200,000—that they would be a more reasonable and formidable force. Similarly, the U.S. Virgin Islands are next to Puerto Rico and may desire to be part of their much larger neighbor. Or perhaps one or both would want to become a part of Florida? On the other end of the spectrum, American Samoa is almost completely isolated from other populated U.S. possessions and therefore they might be better off on their own.

Joining an existing State, though, may be more palatable to Congress as it would ensure no additional Senators would be added to Congress from these lands. Since each State gets two Senators no matter their geographic or population size, the idea of American Samoa with less than 50,000 people having as much power as Texas, California, New York, and Florida may be a bridge too far. But if it were part of, say, Hawai’i—despite being over 2,500 miles away—then its additional population would barely move the needle on the distribution of Representatives in the House chamber.

This, of course, leaves the matter of the District of Columbia. It is an open Constitutional question whether D.C. can even be a State, nonetheless a part of another State. The Constitution (Article 1 § Section 8 § Clause 17) gives Congress the sole ability to create and maintain a federal district to act as “the Seat of Government” and mostly discusses States giving up land to make it possible. Based upon this and other scholarly examinations, it is still unclear whether the roughly 700,000 people in Washington can ever gain equal footing without a Constitutional Amendment, just as the 23rd assigned the district Electors for the Electoral College that previously selected the President; that is, until the most recent set of Amendments retired the Electoral College and replaced it with our current citizen-direct system of mixed ranked choice and negative voting.

However, it is hard to deny that D.C. still has a population larger than even a couple of States, and Puerto Rico more than twenty-one of them. To continue to deny people their rights for going on a century-and-a-half is, as the President said, the antithesis of what American soldiers have fought and died for. In that respect, although the President may lack the power to enact the desired policies, perhaps the shame of a 21st century colonial empire will be enough to shock Congress out of their blasé attitudes towards millions of their fellow Americans.

The above piece is an excerpt from the speculative fiction novel 254 Days to Impeachment: The Future History of the First Independent President by J.P. Prag, available at booksellers worldwide.

Learn more about author J.P. Prag at www.jpprag.com.

254 Days to Impeachment is a work of mixed fiction and nonfiction elements. With the fiction elements, any names, characters, places, events, and incidents that bear any resemblance to reality is purely coincidental. For the nonfiction elements, no names have been changed, no characters invented, no events fabricated except for hypothetical situations.

About the Creator

J.P. Prag

J.P. Prag is the author of "Aestas ¤ The Yellow Balloon", "Compendium of Humanity's End", "254 Days to Impeachment", "Always Divided, Never United", "New & Improved: The United States of America", and more! Learn more at www.jpprag.com.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.