» KEY POINTS

- Surveys like the Census that ask questions around race and ethnicity are inherently flawed because they predetermine the possible selections for deeply held personal ideas about identity.

- Americans are having more difficulty filling in these fields for a plethora of reasons and are skipping these questions or entering confusing answers, yielding unhelpful data and suppositions based on that data.

- Only by allowing free rein responses to questions like these can we get useful data that can be analyzed and re-evaluated over time.

Racial and ethnic categories are social constructs, defined and designed by those who have historically held positions of influence. Our data collection instruments continue to echo this influence...

From “Separating Race from Ethnicity in Surveys Risks an Inaccurate Picture of the Latinx Community” on the Urban Institute blog on October 15, 2019, co-written by Robert Santos—President Joe Biden’s selection for the Director of the United States Census Bureau.

What race am I? If you look at my pictures on my website, you may decide to assign me to a particular race. Yet, did you ask yourself if I feel that way; do I consider myself to be the race you have perceived me to be? Does that race culturally represent what I am? Who do you think you are telling me how I should identify!?! Why don’t I have the right to decide what I am?

This is a struggle many—if not all of us—have. While filling out surveys or paperwork for the doctor’s office or any such thing, we are presented with predefined fields that give a finite list. Sometimes there is an “Other” or “Refused” option, oftentimes not. Even our own government does this with the Decennial Census (like the one that was completed in 2020) and the regular “American Community Survey” that the Census Bureau undertakes in between these larger ventures. The ideas are noble: let us know how many underrepresented people there are and where they live so that we can direct resources there. Unfortunately, the execution has left much to be desired.

Once again, for full disclosure, I worked as an Enumerator for the 2020 Census, going door-to-door attempting to get population information from those who did not self-report. In normal times it would have been difficult; in a pandemic with politically charged overtones, natural disasters, and a constantly shifting timeline it was nearly impossible. Somehow, though, we got the job done, but not without a lot of questions about data integrity. Further, I continue to do occasional work for the Census Bureau and the Department of Commerce, including at the time of this writing as a Quality Control Field Representative for the “Final Housing Unit Follow-Up”. Post publication, I may take on additional temporary assignments as conditions and time permit.

You may say that my experience gives me a bias, and you would probably be correct in that regard. However, I would contend this has also given me perspective to not just my own contentions, but to many other communities who find the question of race one that just does not fit.

» WAVING TO YOUR CAMERA DOORBELL

The quoted Mr. Santos above is one such example. As a Latinx person, he in particular finds it confusing that questions about Hispanic origin are separate from those on race. During my enumerating in communities with large amounts of people of various Latinx descents, a typical interaction went like this...

Me: Are you of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?

Respondent: Yes, I’m Guatemalan.

Me: OK, next question. For the purpose of the Census, Hispanic origin is not considered a race. What race are you?

Respondent: What does that mean? I’m Hispanic, I’m Guatemalan.

Me: Options include White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian or Other Pacific Islander, or Some Other Race. You can chose one or more of these.

Respondent: I’m Guatemalan.

Me: So, “Some Other Race” and fill in Guatemalan?

Respondent: Sure, I guess.

This is not a newly recognized issue. Back on September 30, 2016, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) released the results of a multi-year study about the impact of these questions, noting in part:

Nearly half of Hispanic or Latino respondents do not identify within any of the standard’s race categories... With the projected steady growth of the Hispanic or Latino population, the number of people who do not identify with any of the standard’s race categories is expected to increase...

In order to alleviate this issue, the OMB recommended combining the two questions about Latinx origin and race together as it better reflected how the people in those communities viewed themselves. This is a position that Mr. Santos supported, as he specifically told Congress during confirmation hearings. Although even after he was confirmed he did not personally have the power to modify the question, he fully supported the OMB’s conclusions and said he would strive to see its implementation.

Much to the chagrin of many people, President Trump and his administration chose to scuttle the OMB recommendations and not make them a part of the 2020 Census. In particular, columnist Laura Measher was perturbed because the OMB also made a further recommendation to break out a separate category for people of Middle Eastern and North African origins—one in which she feels she belongs. In the 2020 Census directions, people of Middle Eastern descent were specifically told that they should chose “White” as their race, something that Ms. Measher vehemently disagreed with in her piece “The 2020 census continues the whitewashing of Middle Eastern Americans”. In a correspondence with Ms. Measher on May 22, 2020, she expressed to me:

I know that I and my family members have definitely made good use of the “Other” option on the [C]ensus. My main problem with this is that if “White” and “Other” are our only options, Middle Eastern Americans aren’t accurately counted as a population (at least in the publicly available statistics). Without population data, it’s difficult to calculate accurate statistics regarding Middle Eastern Americans, like poverty rates, arrest rates, education data, etc. And without those statistics, prevalent issues impacting our communities may go unnoticed.

Much like Mr. Santos and Ms. Measher, I do not fit in, either. As a mostly Ashkenazi Jew, I find the idea of being classified as “White” to not only be incorrect, but offensive and repugnant. “White” people slaughtered my ancestors for generations and many “White” people still hold prejudice against me today—including bigotry and antisemitism that I have personally had to deal with. That is not a group I can belong to; it is an insult to my very being in how I see my identity. Thus—like others interviewed by Ron Kampeas in the piece “American Jews: Are you white?”—I chose “Some Other Race” and filled in Ashkenazi. Still, as seen in Mr. Kampeas’ piece, that was not a universal response among people who share my origin. Many had no difficulty in choosing “White” and filling in “Jewish” or something similar (or nothing at all), while others endeavored to leave the question blank. All have led to further complications and issues with the data.

» THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD—PART 1

According to Mike Schneider of the Associated Press in a piece entitled “Census experts puzzled by high rate of unanswered questions”, somewhere between 10–20% of questions on the 2020 Census were left blank, a massive increase from the single digits seen in years past. The questions that were most likely to be left blank were around race, Hispanic background, and sex—all questions about identity. What is more, in a separate article five days later (“Census data: US is diversifying, white population shrinking”), Mr. Schneider noted:

Some demographers cautioned that the white population was not shrinking as much as shifting to multiracial identities. The number of people who identified as belonging to two or more races more than tripled from 9 million people in 2010 to 33.8 million in 2020. They now account for 10% of the U.S. population.

Meanwhile, all those questions left blank and many of the “Some Other Race” selections were filled in by the Census Bureau in a method known as “imputation”. The statisticians at the Census used a court-approved method of trying to guess people’s race based upon other available government or public forms that have been filled out, what other members of the household put in as race, what their neighbors entered, what race their name most likely aligns to based on other respondents, and many other techniques.

The point is, Americans are expanding their own definitions of race, ethnicity, and identity; while the government and society are not keeping up. NPR’s Hansi Lo Wang did a deep dive on the numbers with those selecting more than one race in his piece “The Census Has Revealed A More Multiracial U.S. One Reason? Cheaper DNA Tests” and found that those selecting “White” in combination with “Some Other Race” increased 1,010% between 2010 and 2020—going from 1.7 million to 19.3 million respondents. As the title suggests, the proliferation of personal DNA tests has given people the ability to further define themselves based upon historical origins. My own DNA results show a previously unknown Mediterranean component:

In case you are wondering, my missing 1% comes from my Neanderthal DNA, which is far below the 2.1% average for people of European and Middle Eastern ancestry.

[ * See prior footnote on “Sapien” versus “Sapiens”. ]

While getting a question to tease out non-Homo Sapien origin would be out of the purview of the Census Bureau, DNA tests have at least contributed to the 276% increase in those selecting two or more races.

However, these DNA tests have created a fracturing that is not based in scientific reality. What is being shown in these results is gene flow—how people migrated through time and passed their genes down. It is a probability game of where you are most likely to find pools of these same genes, meaning that they have a common ancestor; it is not an expression of actual race. All studies over the past 25 years have failed to find any part of DNA that is a “race” as we mean it. Skin tones, types of hair, eye shapes, and all of those phenotypes do not align to any part or sections of DNA. Most of it comes from the expression of certain genes, not the genes themselves. In other words, genetically, humans are pretty much exactly the same across the board. Everything we think of as “race” and “ethnicity” are as concrete as “religion” and “belief”. They are less than constructs; they have no material basis.

A better example might be to look at dogs. Whether a Dachshund or a Bernese Mountain Dog, genetically they are exactly the same. As dogs, they are compatible with each other and can have viable offspring (as impractical as that mating may be). We call them “breeds”, but again humans created those through selective reproduction. Finding traits we desired in our companions, we put similar ones together until the trait became more pronounced, and then inbred them to keep that trait. And for analogous reasons, my two short parents preferred to be with a similarly heighted mate, which in turn produced two short offspring.

As such, am I also not just a “breed” of human? What am I but a specific expression of physical traits as homogeneous communities procreated together for millennia? Nothing is physically stopping me from having a baby with any other human on the planet, nor with many other types of extinct hominids like Neanderthals and Denisovans. All these ways of slicing us up have no scientific basis; they are mostly about how others want to prescribe labels to us in order to describe various bodily components and historical origins.

» FLY ME WITH BALLOONS

So if race and ethnicity are meaningless, should we still collect data on them?

In a word: YES!

This again goes back to personal identity. How people view their own being and what communities they assign themselves to is important. All of the reasons we have gone through above and all of the uses the government and other organizations have for these figures is still valid. The problem we have is the method by which they try to generate the data. Being pigeonholed into predefined categories is chaffing at the very least and painfully disrespectful at the worst.

Instead of trying to create categories and shove people into them, is not the simple solution to just ask people what they want to be identified as? Can we not simply ask:

How do you identify your race and/or ethnicity?

It would be an open field and as people typed suggestions could pop up based on what others have previously entered (mostly to try to help with spelling issues), but nothing should stop them from entering their own. Actually, it could actively be encouraged to fill in as many as they feel, whatever makes sense to them. Once we have that data, then we can do an analysis to see what the largest groups are, where they are, how they identify as multiple groups, and all other concerns.

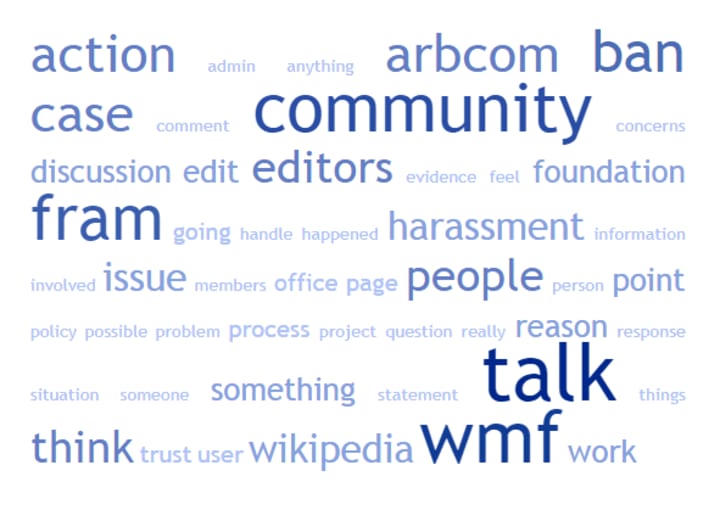

The data could also be expressed as a Word Cloud. As an example, a survey asking for a single word would yield a large array of answers. Those results could then be shown where those that have more responses are bigger and bolder while those with fewer results are shown as smaller and lighter.

This visual representation gives a quick idea of where people stand on any topic, including their identity. Statisticians at the Census Bureau could make suppositions on top of this data instead of trying to fill it in. For instance, they may group “Black”, “Brown”, and “African American” together into a single category for presentation purposes. That is a fine use of taking raw data and transforming it into something useful, while not telling people how they should see themselves.

Does that mean that they would still group Ms. Measher, me, and others under “White”? Perhaps, or perhaps they would finally see these large groups of people who do not want to be in those categories as unique and interesting. Maybe they would figure out new and different sets. Either way, it is impossible to do now because the base data does not exist. You cannot re-evaluate old data if it does not exist because of your collection method!

Gathering data is only the first step in a long process of analysis and debate to get to action. In between, you make data into information and then information into knowledge. Only through this meticulous process can you come to any meaningful decisions about what to do with all of this. But if the data continues to be garbage at the beginning, then the actions of the government and other similarly situated organizations are only going to be a misrepresented gobbledygook for yet another decade to come.

The above piece is an excerpt from Always Divided, Never United: And Other Stories During a Time of Pandemics and Politics by J.P. Prag, available at booksellers worldwide.

Learn more about author J.P. Prag at www.jpprag.com.

An earlier version of this article appeared on Medium.

About the Creator

J.P. Prag

J.P. Prag is the author of "Aestas ¤ The Yellow Balloon", "Compendium of Humanity's End", "254 Days to Impeachment", "Always Divided, Never United", "New & Improved: The United States of America", and more! Learn more at www.jpprag.com.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.