[Author's Note: this essay was written in late 2017, on the occasion of the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation]

In the year 1517, a Roman Catholic monk named Martin Luther nailed a list of complaints to a church door. That seemingly small act of defiance against the Roman Catholic Church is, generally, recognized as the beginning of what has become known as the Protestant Reformation. The Reformation has shaped world history over the past half millennia, in part, because it was not merely a movement to reform a particular religious body, but represented a revolution of thought and ideology that was a dramatic departure from traditional thinking prior to its time.

This fundamental revolution of thought not only separated the Protestants from the Roman Catholic Church but effectively marked the break from the Pre-Modern to Modern Eras. The legacy of Martin Luther, in breaking from the Roman Catholic Church, represented an ideological revolution, that would define the Modern Era by breaking from a holistic worldview, overturning traditional authority and introducing a previously unknown level of relativism into the social fabric.

Although the Protestant Reformation ostensibly began as an effort to address perceived abuses and doctrinal errors that had arisen within the Catholic Church, it very quickly evolved into a broader ideological movement, effectively separating the Protestants into an entirely new form of Christianity. Although much of the resulting ecclesiological chaos was an unintended consequence of Martin Luther's actions, even within his lifetime, Protestantism had already splintered into numerous competing factions.

In all cases, these newly-formed denominations within Protestantism went well beyond the original stated grievances of Martin Luther. In each case, the Reformers departed from traditional Christianity on multiple doctrinal issues. What began as a desire to correct perceived abuses within the Catholic Church soon ventured into the creation of entirely new doctrines and views of ecclesiology. Within a generation, the Lutherans had been joined by the Reformed Churches and the Anglicans, all of which had their divergent variants and strains, none in agreement with Rome, or with each other (Damick 115+).

Protestantism was strongly informed by the rationalism that had become preeminent during the Renaissance period in Western Europe. According to Runciman, “Luther himself was a reactionary in temperament, disliking the spirit of the Renaissance. But his leading disciples were children of the Renaissance” (239). The Roman Catholic Church, too, had incorporated Renaissance ideology by that point, but the Reformers applied rationalism and humanism to their faith to a far greater extent. The effect of this was that the Protestant’s view of their religion, and the world at large, would become much more materialistic.

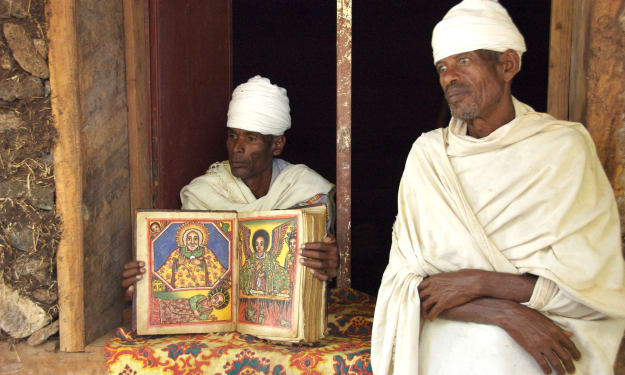

Despite differences in beliefs, all major religions in the Pre-Modern world shared a certain holistic view of their universe. Mankind was not completely detached from the spiritual realm in the Pre-Modern paradigm. Protestants, on the other hand, would discard many Christian practices as superstition. For instance, traditional Christianity prior to the Reformation, practiced prayers for departed souls, as well as entreating departed saints for their intercessions. This was true, as well, within Judaism, which preceded Christianity and remains so (Goldstein). To this day, traditional forms of Christianity also continue these practices (Orthodox Church in America), but the Protestants have wholly rejected them. In fact, some of the scriptural references for this practice were simply expunged from the Protestant biblical canon (Orthodox Study Bible, 2 Maccabees 12:42-44).

In one of the more dramatic undertakings by Martin Luther himself, numerous books of the Old Testament were culled from the Bible (Orthodox Study Bible, XIII). Considering that these rejected books of scripture had little, if anything, to do with the original grievances against Roman Catholicism, this does not seem to fit with the idea of reformation.

Up until that point, all expressions of Christianity, from the earliest centuries, had accepted these books as valid scripture. This was not confined only to the Roman Catholic Church. To this day, all Pre-Reformation forms of Christianity continue to use the original canon of scripture, with few differences among them. The altering of the Bible, by Martin Luther and his successors, represented a radical departure from traditional Christianity.

The Protestant Reformation would eventually overturn the accepted authority of the church, whose hierarchal structure had existed since the Apostolic Era of the New Testament. Writing for the Ecumenical Review, Kwok tells us that:

"Luther differentiated between the true church and the institutional church on earth. He did not believe the pope or the Roman Catholic Church represented the true church, even though the pope claimed to be the successor of Peter and served as the figurehead of Christendom. The true church, for Luther, is not based on succession of inheritance, but is supported and guided by the Holy Spirit. Luther attacked papal authority, clerical privilege, and the sacramental system". (237)

The problem with Luther’s thinking, if he were truly seeking to encourage reform, is that his positions were contrary to the beliefs and practices of all the ancient Churches. The Orthodox Churches of the East would agree that the Pope of Rome was not the sole successor of the Apostle Peter and did not have a legitimate claim to universal authority. That was one of the sources of the rift that had occurred between them centuries before Luther (Whalen). However, much of the rest of Luther’s attack on institutional Church authority was not in keeping with traditional Christianity (Runciman 269).

All Churches held to a sacramental system, though they would have taken issue with some of the alleged abuses of Rome, just as Luther had. Furthermore, the authority of a bishop over his Church was a given throughout the Christian world. That in itself had not been a cause of conflict between Rome and the other ancient patriarchates. The Papal claims to authority over other bishops and their Churches was the issue. Luther’s positions were not a corrective, returning Rome to its previous practices, but were innovations that inherently rejected more than just what he claimed on the surface.

The overturning of Church structural authority was gradual. The earliest Reformers maintained a structure that was more similar to the Roman Catholic Church than later Protestant theologians would consider acceptable. In later generations, the denominations springing from what became known as the Radical Reformation, as well as the eventual Evangelical movements within Protestantism would wholly democratize their ecclesiological structures.

It can be well argued that Protestantism gave birth to democracy (Ryrie). Turning the hierarchal structure of the Pre-Modern era on its head, most Protestant denominations are ordered from the bottom up. Rather than accept the authority of any central figure or even a governing body, local congregations rule their denomination from the bottom up.

Many congregations are non-denominational, adopting their own particular set of beliefs, with little regard for unity with others. Indeed, in practice, each adherent is free to interpret and practice their religious faith as they see fit, as opposed to accepting a preconceived set of beliefs and precepts. Ironically, even though different congregations and even individual Christians may hold contradictory beliefs, there exists among them a general acceptance of their theological opponents. This level of relativism was unknown in Christianity before the Reformation and is alien to Pre-Modern thinking. Regardless of religion or philosophy, Pre-Modern man generally accepted that truth was absolute, even if they disagreed on what that truth might be.

As Protestantism splintered into more and more competing denominations, all while claiming to approach scriptural interpretation and doctrine from the same point of view, their more relativistic explanation for their differences evolved as a means to present an outward veneer of unity. Eventually, this shift to a relativistic worldview allowed for the introduction of secularism, which is, essentially, the separation of church and state.

In the holistic Pre-Modern world, the spiritual and temporal were connected, so the idea that religious life could exist separately from civic life was a foreign concept. This acceptance of theological relativism not only allowed for the development of secularism, it is also underlying the progressive ideology that underpins most aspects of the Modern Era. Jason Farr, writing about the consequences of the Westphalia Treaty, attributes the development of the modern nation-state to Protestantism and, indeed, secularism is one of the linchpins of any such nation-state (Farr, 156+). Progressivism is often associated with the Enlightenment, but without the Protestant Reformation, it is difficult to imagine the conditions existing which would allow for the Enlightenment.

The seeds of Progressivism had already begun to blossom in the Protestant Reformation. By introducing a de facto relativism into Western European society, each new Protestant denomination came into existence as an attempt to improve, or correct, those which came before. While the predecessor denominations did not agree with the doctrinal innovations of the splinter groups, they continued to broadly accept their legitimacy. This, of course, is a form of relativism, but the ideology goes beyond simply that.

This ideology inherently concludes that even the most critical of human matters, in this case religion, can (and should) be fundamentally improved upon. It can be conceived as a form of Nihilism, in which the old order must always be overthrown to make way for the new, improved order. “The path of Nihilism…has been "progressive"; the errors of one of its stages are repeated and multiplied in its next stage” (Rose).

From ancient times, Christianity had remained largely static. To be Christian meant to adhere to specific, fundamental beliefs. Members of the faith held that these beliefs represented eternal truths. There was no salad bar approach, where one could pick and choose the ingredients they preferred. By applying a relative and progressive ideology to the Christian faith, generations of Protestants would increasingly distance themselves from the traditional Christian view that the faith constituted a specific set of precepts.

As Protestantism spread throughout Western Europe and, later, became a dominant force in North America, such relativism and progressivism became the norm within society. Whatever one group believed was good enough, even if those beliefs wildly contradicted the beliefs of other denominations. From the Enlightenment era to the present day, these factors that were born of the Protestant Reformation have been accepted as norms that extend throughout civic life.

It has been the contention of Protestants, both at the time of the Reformation and now, that their movement was one of returning the Christian faith to its original, purer form, in response to the theological corruptions of the Roman Catholic Church. The proliferation of tens of thousands of Protestant denominations, with their myriad of beliefs, make it difficult to accept that the Reformation included a return to a singular, earlier version of Christianity. If that were the case, which from among the multitude of denominations represents that singular Early Church?

The Reformation was defined by a rejection of Roman Catholic practices and doctrines, while largely presupposing that the Catholic Church was the only Christian institution at that time. In fact, there were other, older forms of Christianity. The doctrines of the Protestant Reformers and their numerous successors were a departure from the beliefs of those Churches, as well. One might be more sympathetic to the proliferation of newly constructed doctrines if it weren't for the fact that early Protestant theologians had some degree of familiarity with other traditional forms of Christianity.

The Roman Catholic Church and the other ancient Christian patriarchates had, indeed, separated themselves from each other in the 11th century. As clerics and theologians of the Roman Church, the earliest Reformers, at the very least, would have been aware of this. For his part, Martin Luther was certainly aware of the existence of these older, traditional Christian churches. He, and other early Reformers, held these ancient Churches in high esteem. They did so in principle, at least, during the early stages of the Reformation (Luther). Soon, however, they found themselves forced to reject these churches, as well, when the Orthodox Christians of the East failed to endorse their newly constructed doctrinal principles.

Looking objectively at the original aim of reforming the Roman Catholic Church, it must be viewed as a failure. They changed the world, but did not accomplish their own goals in the slightest. The Reformers did not turn back the clock of Rome to a former point along the theological continuum, nor did they return to an earlier form of Christianity. Instead, they continued to tinker with Christian theology until they had fashioned a seemingly endless variety of doctrines of their own creation.

For any modern-day Protestants who still wish to revisit traditional Christianity, the five-hundredth anniversary of Luther’s revolution should provide the perfect opportunity to reassess their journey and make good on their mission.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Works Cited

Damick, Andrew Stephen. Orthodoxy and heterodoxy: finding the way to Christ in a complicated religious landscape. Ancient Faith Publishing, 2017.

Farr, Jason. "Point: the Westphalia legacy and the modern nation-state." International Social Science Review, vol. 80, no. 3-4, 2005, p. 156+. Global Issues in Context

Goldstein, Zalman. “Kel Maleh Rachamim – Prayer for the Soul of the Departed.” Chabad.org, www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/367837/jewish/Kel-Maleh-Rachamim.htm.

Kwok, Pui-lan. "Reformation unfinished: economy, inclusivity, authority." The Ecumenical Review, vol. 69, no. 2, 2017, p. 237+. Religion and Philosophy Collection.

Luther, Martin. “Full Text of Luther’s Works Volume 32: Career of the Reformer.” Edited by Helmut Lehmann, Internet Archive, Internet Archive.

Orthodox Church in America. “Common Prayers – For the Departed.” Orthodox Church in America, oca.org/orthodoxy/prayers/for-the-departed.

Orthodox Study Bible. Thomas Nelson, 2008.

Rose, Eugene. “Nihilism: The Root of the Revolution of the Modern Age.” NIHILISM: The Root of the Revolution of the Modern Age, Orthodox Outlet for Dogmatic Enquiries, 10 Dec. 2011.

Ryrie, Alec. "Three surprising ways the Protestant Reformation shaped our world." CNN Wire, 29 Oct. 2017. Global Issues in Context.

Whalen, Brett. “Rethinking the Schism of 1054: Authority, Heresy, and the Latin Rite.” Traditio, vol. 62, 2007, pp. 1–24.

About the Creator

Randy Baker

Poet, author, essayist.

My Vocal "Top Stories":

* The Breakers Motel * 7 * Holding On * Til Death Do Us Part

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (1)

By delving into the ideological, theological, and societal implications of this historical event, you offer valuable insights into the complexities of religious and intellectual history. Well done!