Examining the Excuses

Why People Don't Vote

If I were to tell you that the most powerful people on the planet are the one's who don't vote, would you believe me? If your immediate answer is "No", I wouldn't blame you. As a registered voter, myself, I have participated in every election since I became eligible. To me, the act of voting for public officials is one of the most important things one can do in a democratic country, and I see it as my civic duty every November 8th. However, and it may not surprise many when I say this, but a large amount of people in the United States, as well as around the world, don't exercise their right to vote. They are, in essence, voting not to vote. Moreoften than not, you'll hear one of two things in regards to the issue of why people don't vote. Either you'll hear a remark of shock/dissapointment followed by "Well, if they didn't vote, they shouldn't complain." or an excuse as to why other people (or they themselves) refuse to exercise their right and participate. By the time you've finished reading this, we will have went through some of the main reasons/excuses as to why people choose not to vote; as well as establishing some refutations; encouraging others to reevaluate such stances on the matter.

#1) I don't vote, because I think the candidates suck.

Focusing exclusively on the United States (in this case), voter turnout for the plethora of the country's elections has been shown to be ower than other democratic countries. Part of this, is due to the lack of any law which requires voting to be mandatory. However, the turnout has been proven to be highest during the general elections coinciding with the presidential elections. Percentage-wise, the presidential election of 2020, had the highest turnout of voters since 1900 (66.9% compared to 73.2%). Certainly an impressive effort; however, it was determined that for all those who did vote in 2020, roughly 1/3 of all eligable voters refused to participate. Which equates to, approximatley, 80,000,000 people. Furthermore, throughout most of the presidential elections in American history, the turnout rate has lingered in a range between 50% & 65%. Just to give some examples, the presidential elections of 1980, 1992, 2000, & 2008, generated turnout percentages of 54.2%, 58.2%, 54.3%, 62.5%.

Such numbers only drop lower during midterm elections. Such elections that take place during the half way point of a president's four year term, have only had turnout rates of between 35% & 45%; with the highest turnout being the 2018 midterms, at 49.4% (the highest since 1914). Yet, for local elections, the numbers drop even lower than that. These are held annually, with an estimated turnout of only 15% to 27%. Given that there is a sufficiant amount of evidence blaming the system of plurality voting in the United States' elections (that being the choice of only one candidate on the ballot, and the candidate with the most amount of votes wins) for the lack of motivation amongst the eligable population.

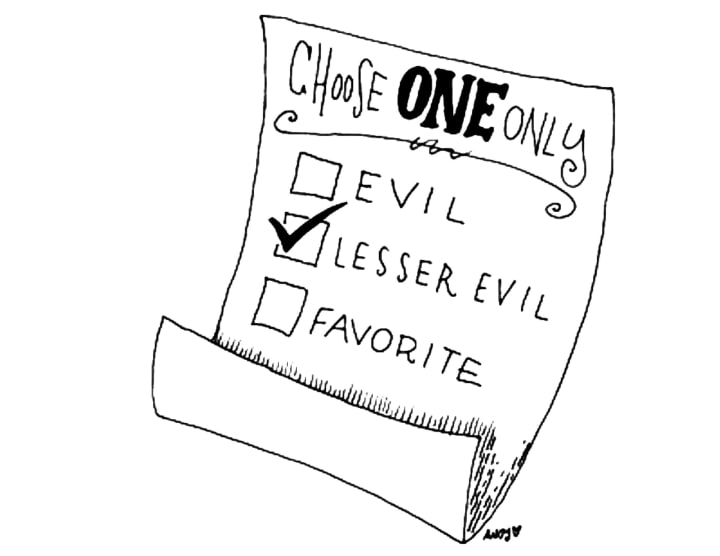

Compared to other countries, like Germany, Japan, Australia, Ireland, and Argentina, where voters choose their public officials based on a system of proportional representation, the voter turnout has proven to be much higher. This is due to how plurality voting reinforces the duopoly of the two party system & often gives the impression of intimidation for voters to pick the lesser of two evils. Especially when most Americans identify as "independent" and have no formal affilitaions with the two major political parties (neither Democrat, nor Republican), and more often than not, are disillusioned by the choices available come election day; choosing instead to protest the entire system & not vote. Despite the fact that they could easily vote for a third party candidate and have that vote count in the process. They could also participate in primaries and caucuses as a means of influencing the nomination of a desired candidate within the two major parties. Yet, this process has been proven to be more complicated than it appears to be, on paper. Especially, if the primaries are closed; leaving the ultimate method of who recieves nominations up to the system of plurality voting. Which also leads us into the second excuse.

#2) I don't vote because the candidate I like has no chance of winning.

Closely related to Excuse #1, yet this excuse slightly differs, due to the influence of the electoral college. Unless you live in a swing state, where party affiliation goes back and forth throughout the course of multiple elections, the feeling of your vote not making a difference is quite strong. For example, during the 2008 Presidental Election, in the state of Idaho the Republican candidate, John McCain, recieved 61,21% of the popular vote. By contrast, the Democratic candidate, Barack Obama, recieved only recieved 35.91%. For a democrat living in Idaho, why would they feel it important to participate, when the party they support, has almost no chance of winning, and the state's electoral votes consistently lend themselves to the opposition?

#3) I don't vote because of all the obstacles.

Pertaining to the United States, once again, there are a number of barriers and restrictions that prevent people from voting. Depending on their occupation or academic obligations, some people cannot get off work or school to vote on Election Day. Especially, since there are a limited number of hours when the polling places are open for in person voting; and even if your home state has some form of early voting, many others don't. Furthermore, the differing state laws which determine who's eligible to vote and who isn't, only makes the process more convoluted. Out of the 50 states that make up the U.S., 18 states require or request voters to have a valid photo I.D., 17 states require or request a non-photo I.D., and 16 states have no I.D. requirements at all. Some states even require you to register to vote; and even if you are registered, sometimes, officials can conduct what it called a voter roll purge, and deregister large groups of voters at once (often without even notifying them of their spontaneous ineligability).

For many recent immigrants to America, whos first language isn't English, voting can be extraordinarily difficult. From not knowing where polling places are located, to not understanding information on the ballot. Also, due to a declining number of polling places and funding for election offices, in recent years (despite an increase of the national population), many voters have encountered long lines in order to vote in person. Other reasons people may not be able to vote in person is due to physical disabilities, or a recent move to a different district, where there is a limited amount of time to mail in an absentee ballot. With all of these hinderances put in place, many people simply come to the conclusion that it's not worth confronting them, and choose to stay home.

#4) I don't vote because my one vote alone is not not going to make a difference.

Moving on to a much larger, international level, many people argue that because their systems of government are so corrupt beyond redemption, any form of voting is just a social construct designed to give the illusion of empowerment to the individual citizen; becoming so disenchanted with politics, that their vote seems objectively meaningless in the grand scheme of it all, and that no amount of votes in the world could ever fill the quota for the changes needed in order to make things better. In fairness, this excuse actually has some validity in an idealistic & mathematical sense (bear with me).

The phenomenon referred to as "The Paradox of Voting" states that the act of voting involves a both a benefit and cost to the individual voter. The benefit comes from the voter directly changing the outcome of the election to the one that is desired (in such a case, the voter is believed to be of utmost importance). However, the probability of this actually happening is very low. Therefore, the expected benefit is miniscule. The costs of voting include the use of time and direct travel costs, and calculations show that the cost is typically much larger than the expected benefit. The individual and rationally-minded voter should, therefore, not vote.

#5) I don't vote becuase I don't care about politics.

They're just not political. Simple as that. They don't see how what these public officials do have any relevance to their day to day lives. Who cares if Poindexter Putz won against Farty McBobo? It aint gonna change no nothin', round here. Will it? ... Well, yeah. It will. You see, these politicians DO affect your daily life. Not one day in your life will go by, without being affected by the actions of your government. From the water you use to take a shower in the morning, to the sales tax inlcuded in your morning coffee you grab on the way to work, to the roads your drove on your commute, to the quality of air you're breathing right now as you're reading this. All of these things are determined by government action (or lack thereof). The influence of government is unavoidable, because it's everywhere.

Secondly, allow me to go back and refute the voting paradox by means of a little thing called "Reality". Your individual vote can make a difference, and numerous elections have been determined by a single vote.

- In 1839, Jacksonian Democrat Marcus Morton won the 1839 Massachusetts Gubernatorial Election by just one vote; finishing with 51,034 votes out of 102,066 (the bare minimum to receive a majority, and avoid sending the decision to a vote in the opposition dominant, Whig Party, state legislature).

- In 1910, when United Kingdom Conservative Henry Duke eked out a victory against Liberal Harold St. Maur for a seat in the House of Commons, the incumbent Duke came out on top with a total of 4,777 votes, against St. Maur's 4776.

- In 1961, Zanzibar's Afro-Shirazi Party took home 10 of 22 total seats in the Legislative Council to the Nationalist Party’s nine; winning the district of Chake-Chake, and the most legislative seats, by a vote of 1538 to 1537.

- In 2008, an Indian politician C.P. Joshi lost by a one vote in arace for the assembly position in the North West Indian state of Rajasthan. In the final tally, Joshi lost against Kalyan Singh Chouhan, by a total count of 62,216 votes to 62,215 votes.

- In 2022, a race between Republican Tony Morrison and Democrat Christopher Poulos to represent the 81st Assembly District of the Connecticut State Legislature, resulted in a final tally of 5,297 to 5,296, in favor of Poulos.

At the end of it all, voting comes down to having your voice heard. Tell me one person who doesn't want that. People go out of their ways to tell other people about their favorite foods, sports teams, movies, and fashion brands; so, why wouldn't you want others to know who should have power over you? That's what we do when we vote. Granting certain individuals to have more power over us, and more control over our communities. Those who don't vote are often the least represented, and only further fueling their animosity towards the system. Arguably these are the same people that should be voting. So, let's turn that around. I vote that you vote, & I hope that you vote that I vote.

About the Creator

Jacob Herr

Born & raised in the American heartland, Jacob Herr graduated from Butler University with a dual degree in theatre & history. He is a rough, tumble, and humble artist, known to write about a little bit of everything.

Comments (4)

so interesting!

Excellent article. I believe that if just 1% or 2% more people would have voted in the 2016 election the results would have been different.

Excellent arguments and the tories in the UK are taking down the republican path and so many in the electorate have those excuses, I believe in Australia you have to vote , it should be compulsory and simple, but governments aredoing far more gerimandering and voter suppression.

Excellent examining the excuses!!!💖💖💕