The Christie Pits Riot— OfPublicInterest.02

Could aloneness have stopped the Nazis?

When Canadian newspapers began publishing the Nazi party’s anti-Semitic policies across their front pages in the early 1930s, it seemed to intensify an already tense period. The Great Depression was in full swing in Canada and anti-immigrant sentiment was already strong. With millions of Canadians hit by unemployment, hunger, and homelessness, many saw the way the Nazis were handling the Jews in Germany, dismissing them from professions along with outbursts of violence, as a validation to act, rationally or not, for their own struggles.

Not that they needed validation from the Nazi regime. Anti-Semitism and anti-immigration were already well indentured into mainstream Canadian society at the time, after the Jewish population grew from a couple thousand around 1870, to 100,000 after World War I. The news from Nazi Germany just served to provide an excuse, albeit irrational, to act. Irrational because Jews were already second-class citizens in Canada, where they were often refused work, enrolment at universities, and prohibited from certain neighbourhoods. Jews hardly took up space in the economy as things were; but, perhaps they simply provided something for angry, entitled and unemployed Anglos to punch down on. Yes, that’s right, Anglo’s.

This story is perhaps the most muddled prologue to World War II that I have ever come across; here’s why. In 1933, Toronto was predominantly populated by British immigrants who, no surprises here, hated any other type of immigrants. They had strong social organisations that were anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic. This means no Jews, no Italians. Which is where it gets ironic given the way history unfurled. The British-Canadians, seeing the news from Nazi Germany, began ‘Swastika Clubs’ aimed at making Jews feel unwelcome, particularly in the beaches area of Toronto.

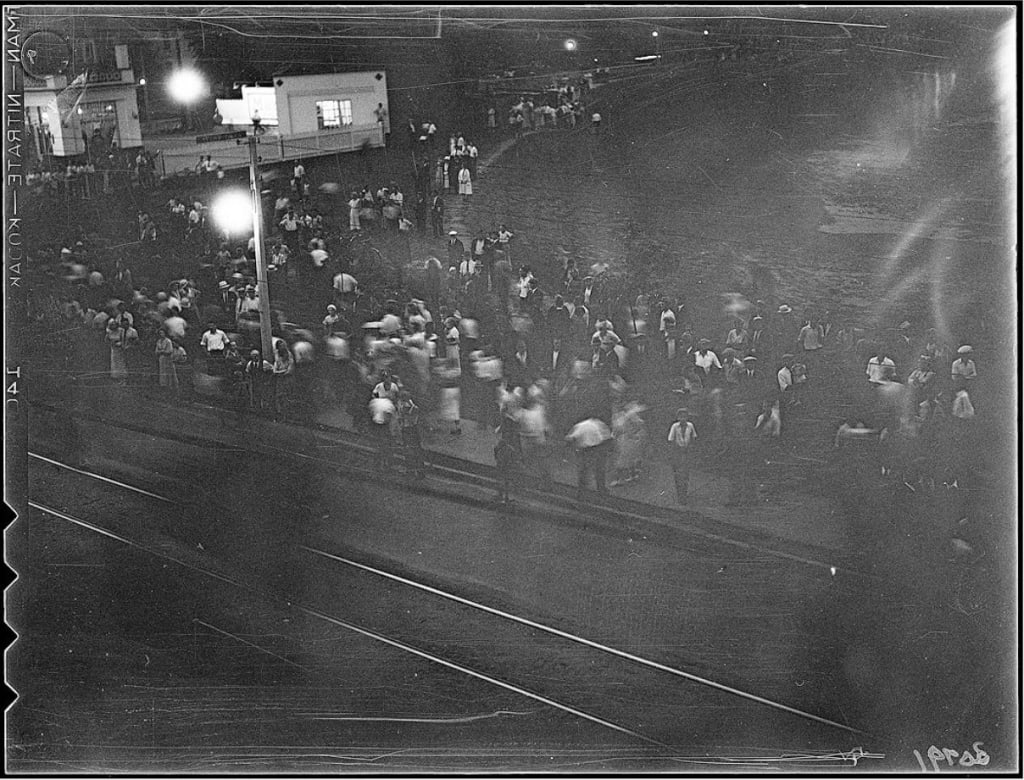

Over two August nights in 1933, already high tensions between the British and the Jews and Italians began to boil over at a local baseball game. The game was at Christie Pits, home ground of the Jewish Harbord Playground baseball team. Members of a local ‘Swastika Club’ were there, waving flags emblazoned with the Nazi emblem and shouting ‘Heil Hitler’ amongst the crowd in an effort to stir up the Jews. Two days later, there was another game, and there were the same provocations. Only this time, violence broke out. And not in the way a couple of meatheads might punch on in a dim carpark outside of a shitty bar. As the Jews tried to grab the swastikas, the entire park erupted in an all-out melee involving baseball bats, lead pipes, and truckloads of reinforcements. Jews and Italians versus the British-Canadian Nazis and any other Anglo in the area. All told, The Toronto Daily Star reported that 10,000 “wild-eyed and irresponsible young hoodlums” beat the crap out of each other that night.

Thankfully there were no deaths. But the irony that the British-Canadians were pushing Nazi ideals into the August air, and Italians fought alongside the Jews is not lost on me.

* * *

Pure as we begin

Here we have a stone

Throw to stay the stranger

Swore to crush his bones — Maynard James Keenan, Intension

The juxtaposition between who stood for what that night at Christie Pits and then six years later in World War II tells me that it doesn’t matter who we are or who they are, we just need to hate the other. We’re too scared of aloneness and too weak to find ourselves in solitude, so we seek a shared identity, a shared truth, with other people. When one person starts shouting, and then another, there’s suddenly something obvious on our doorsteps for us to latch onto. We form a mob because we’re too gutless to face one. I don’t think that we actually believe anything that the 1 % have to say, they’re just very good at seeking out our insecurities and fears and making us feel foolish if we don’t stand for something. Even if that something makes absolutely no sense. And we’ll convince ourselves that we do believe it.

The beliefs that people hold may be completely fallible. But the reasons why they hold or are susceptible to those belief structures are completely valid. They’re just not vivid reasons, at least not in the way that their beliefs are vividly displayed. That’s because some perfect storm of childhood conditioning and trauma leave them perfectly incapable of rationally dealing with the moment, so they panic and believe the story that rattles their insecurities and unprocessed fears the most. Triggered people react by punching down in non-sensical ways. This is in no way a validation of any beliefs or of the actions taken for them, but of the fallibility of the human experience.

So, in a way, the hate that they fight for does make sense, just not in a way that’s obvious to them or anyone else. Not because they’ve collectivised for a cause, even if they think they have, but because they subconsciously find coalescence, towards the person shouting fear in the town square, based of trauma conditioning and response mechanisms. Those Jews and Italians in 1933 Toronto were not the problem with the economy; the fact of socio-political identity meant that the British-Canadians would hardly blame themselves. The minority Jews were as convenient for their egos as they were for the Nazis.

The gathering of Nazi mobs against Jews, as with any hate group, was an act of cultural narcissism, a collection of people that can’t see the forest of their egos for the trees. Gathered together to say ‘it’s not us, it’s them’, while really only caring that they as an individual can feel better at having someone else to blame. In being so blinded by their childhood protection mechanisms, they were unable to love and accept themselves at a personal level. Which means that they could’t see that it’s impossible to subscribe to and share an identity with another. Because ultimately, when those rioters left Christie Pits in their factions and then split off into their homes, they were unaware that who they thought were their kind were probably the next day arguing for another cause that they stood against. We may find resonance with some, and there’s joy in that, but it will never be 100 %. The sooner that we all realise that joy is only shared momentarily before we move on, then the sooner we’ll stop hating each other in illogical ways.

As beings with incomplete perceptions, we place idealistic expectations on things that we find joy in; we chase the dragon, it’s addictive, and it ultimately leaves us miserable when the joys turn out to be misaligned in some way. We want the joy to be everything to us until it becomes the gritty sandy feeling of stress in our blood. Have you ever fallen in love with someone so completely that you ignored the red flags until all you felt was pain? That’s the point here. This mob mentality is adolescent, we’ll forsake boundaries to find shared truth and to be accepted when we can’t accept ourselves. To be accepted, we’ll lose sight of ourselves and maybe even stand up for hate and do the most terrible things.

Perhaps it’s obvious by now, but I don’t think shared truths can exist. There are relatable and unrelatable elements in all humans, given some variation on the balance, some more relatable than others for sure. But human experience is too unique, and perspective too narrow, to find shared truth. People coalesce into their communities for completely different reasons, but the multitudes of communities and parallel lives that we each live in are a testament to the un-cohesiveness of our complete truths.

Where we draw our social lines is where we’re afraid of aloneness. When we choose to take more responsibility for ourselves at a deeper personal level, we’ll find that the only line to draw is around ourselves. Then we can say, I see you.

* * *

Follow this project by subscribing to my profile on Vocal. And I encourage you to sign up here to unlock all the benefits of becoming a Vocal+ member. Find what you want to read, anywhere, anytime. I signed up, no regrets.

This essay is dedicated to Chris, who asked me to write about the Christie Pits riot.

About the Creator

Jacopo Mulini

Sometimes fictional, sometimes philosophical, sometimes biographical, but mostly as a blend. These stories are my journeys through my loves and my shames, my ego and my empathy, and my detached wormhole thoughts.

@microbesandtheuniverse

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.