The Art of Being Transfixed

An Artist’s Reflection

This reflection was inspired by reading an article from the Psychology Today website, Feeling Intensely: The Wounds of Being “Too Much” by Imo Lo, Psychology Today psychotherapist, art therapist, coach and author of the book Emotional Sensitivity and Intensity. Lo talks about some people having a much greater sensitivity than others and looks at both positive and negative aspects of this personality type.

One of the dot points in Lo’s article was this:

‘When you become absorbed in your love for a piece of art, literature, theatre, or music, the outside world ceases to exist.’

This simple statement led me to thinking about the times that I have been absorbed, and what by. Going one step further, I will call this the state of being transfixed, when the outside world ceases to exist for a moment.

Immediately springing to mind was the time I was about 19, sitting in the carpark one afternoon, waiting to start afternoon shift at a tool factory in Moonah, Tasmania. I was sitting at a table playing my transistor and the most beautiful, rolling piece of classical piano came on. I was transfixed, transported to a world beyond the carpark, the tool factory, the ordinary. I could not move, even when I knew this would make me late for work, even when I noticed and ignored the other workers going in, or the siren that announced the start of the shift. I stayed in the world beyond for as long as it held me, until the piece had finished, until it was complete, until I had absorbed it into my being. I was transfixed.

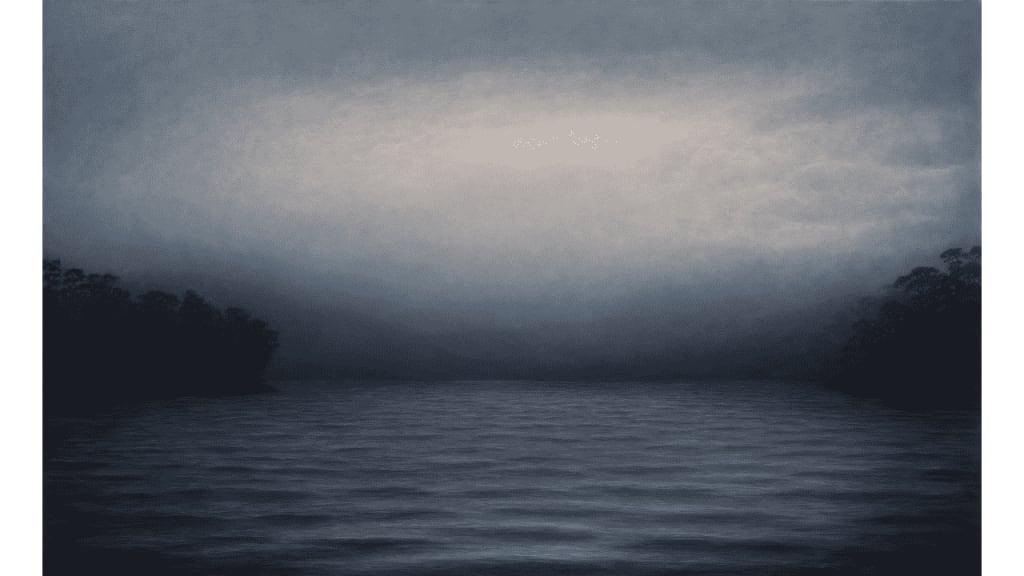

I also think about the time a few years back when my mother and I went to Handmark Gallery in Salamanca and stood in front of Michaye Boulter’s painting of coastal Tasmania, a view from the water. Misty, moody, the perfect palette of greys and soft hues, capturing one of the special moments in a beautifully painted evocative seascape. What made that painting so powerful for us, I think, was that we stood in front of it from a place of knowing. This painting was within us, we knew it. Not the place exactly, but the Tasmanian coast from the water, the Tasmanian coast in all its different light and glory. The mystery, the intrigue, the sense of something old, ancient, enduring.

Behind Michaye’s paintings is her deep connection with the sea, the coast, the light play on the water through the atmosphere. Her works are informed by her experience. They come from that place of knowing, of having lived the work, having absorbed nature into the psyche, to have felt it in a way that sees and knows at the same time. These works become a much deeper expression of her inner response to her world, and her skill to express her inner knowing is backed by informed research through practice.

I thought about other times I was transfixed, and the time I visited the Biennale of the Everyday in Sydney with a fellow artist friend and colleague in the Master of Visual Arts program in 1998 (I later deferred and re-enrolled a few years later to complete my MVA in 2016). There were a couple of very powerful, minimal installations included. One of these was a video installation by Thomas Struth , installed in a building that was round with a high ceiling. Surrounding the inside, projected extremely large and quite high, were videos, each screen filled with a person’s face. There were 8 or so faces projected around the room. The subjects must have had to stand in front of the camera for an hour and remain expressionless. The art of remaining expressionless is quite hard it seems, as the mind wanders.

My friend and I stood transfixed, but not in an emotional soul stirring way that my mother and I were with the Boulter painting, but in an engagement of scrutiny, a reading of the micro-expressions that we found ourselves to be observing, We noticed through observing the subjects performing the art of standing still, letting the world around them continue, and endeavoring to remain expressionless, that eventually the untrained human mind will wander, and wander it does into the depths of one’s own memory or thoughts of the future. This became apparent, the longer we watched the video. Jonathon Watkins, artistic director of the 11th Biennale of Sydney, in his catalogue essay Every Day (p.16 of the catalogue) notes that ‘the small involuntary movements in their faces are more eloquent than any super-imposed commentary might be, the time-based nature of this work enabling a rare intimacy.’

My friend and I found ourselves interpreting the moments that we recognised some shift in cognition of the person we were observing. It seemed to us after a while, that these micro-expressions showed when a person was reflecting a memory going on inside their head. After a while of viewing we felt strongly that these memories, these things that we connect to, make us human. The longer someone maintained complete expressionlessness, it became like a wall between the viewer and the subject. This wall, so to speak, became dropped when the viewer connected to the recognition of an emotive thought. We all, at the base of our being, understand raw human emotions, the subtle emotions that connect us on the level of empathy to another human.

We noticed that one of the video subjects took a long time to show any micro-expressions. The longer we observed him in contrast to the others, his face took on the appearance of a mask, a stone wall built up over time to conceal the inner emotions to the world, a practiced face, a shield. He was older than the others, and we thought that may have been a factor. Also, he may have committed to not cracking and taken it on as a task. Standing in front of a camera, as the art subject to be projected onto a screen at an international art festival would be quite a daunting thought, and yes, you may want to keep your privacy shield up. Not letting the unknown masses in, is probably a good enough reason to be able to maintain the mask for a longer time than others.

Eventually though, there was a moment that we both jumped at, and it was the moment where the subject’s eyes misted, and we saw his Adam’s apple rise and fall, and his eyes gain a faraway look for a moment. We recognised that he had had a thought which connected him to his emotions, and we were quite excited by it. I remember we said, ‘look he is human after all!’, because there is something quite alienating about the mask, about someone not connecting to their emotions. After all, it is understood that although the body may be imprisoned, our thoughts can offer the freedom we desire. (Eckhart Tolle speaks on his experience teaching prisoners. The Power of Now.)

Eckhart Tolle tells us that everything that is essential is invisible and he relates this to memory, for example, he says, if asked to recall your grandmother, you can instantly recall her, or the house you lived in when you were 8 perhaps. He tells us that we are not our mind …

I believe it is focus, that allows an artist to tap into their inner well to create works that connect on another level. Focus is informed through consistent research and practice, focus that is trained and disciplined can achieve an expression, a visual representation of the artist’s inner and outer worlds. This can be a journey of the mind or the emotions, or a bit of both.

I also believe that those seeking food for the mind will search out the types of information they want to immerse themselves in, and that is a personal journey, or sometimes a public one, however our emotional responses to things are ours alone.

Our emotional responses are innate and conditioned at the same time through our knowledge, the place of knowing, our intuitive space. These emotional responses can be monitored by the brain, but they are felt much deeper, and in feeling we connect to each other, through a place of understanding, a place of knowing.

This is why, I think it is often hard for people to understand the greater stages of grief or loss if they have not yet experienced it, or the unconditional love that is felt at the birth of your child, and various other human emotions. We understand though small experiences, but the greater depth of understanding is not truly experienced until it comes from a place of knowing. Sometimes children though are extremely perceptive and intuitive in their knowledge responses, something innate, aware, and uncluttered by experience perhaps.

Anyway, I believe being transfixed is a state of presence, being moved by something which happens through our emotions, rather than our analytical thought. A response to something that connects us beyond logic, triggering feelings, emotions, and empathy, with a person, or a piece of art such as the Boulter. The ability to transport someone into a familiar space of knowing, to something ancient within us is a place we can recognise, even for those unfamiliar with the Tasmanian coastline. The Michaye Boulter painting taps into something much more universal. It is descriptive yet void of human subject matter. It is a description of a landscape, not only of the coastline, but a landscape of the mind, a place where souls connect.

I believe it is these secret spaces of the mind where we connect, that made this an extremely powerful painting, and it ‘spoke’ to us. What if my mother and I had not been Tasmanian, and had not a sense of knowing this place, this coastline, this light, this mist, this tonal palette of softness? Would this painting have had the same fixation for us, the same magnetism and awe? I believe so, but I speak from a point of bias and knowing and so my reflection on this point is unfounded, other than I believe this represents an archetype of sorts, a primeval landscape within the mind. A resting place for the eyes and the mind. A place of no thought, of just being.

Eckhart Tolle also talks about the importance of just that kind of space in our minds, the space between our mind and our consciousness. Mind, no mind.

The Wikipedia page on Art and Emotion talks about the relationship of art and emotion in a study by Art Historian Alexander Nemerov who says, ‘emotional responses are often regarded as the keystone to experiencing art and the creation of an emotional experience has been argued as the purpose of artistic expression’.

The article also points out that ‘research has shown that the neurological underpinnings of perceiving art differ from those used in standard object recognition’… ‘Instead, brain regions involved in the experience of emotion and goal setting show activation when viewing art’.

Furthermore, the article puts forward the idea that there is certain basis for emotional responses to art, such as, ‘evolutionary ancestry’ that ‘has hard-wired humans to have affective responses for certain patterns and traits.’, e.g., pattern recognition and symmetry.

At this point I recall reading somewhere that people wept in front of some of Mark Rothko’s paintings. The effects of colour upon the psyche and emotions are well documented and now the psychology of colour is also used in advertising as a trigger to the subconscious mind. Colour is made up of wavelengths of light, and light in the landscape can have an effect on our emotions.

The thing that Rothko and Boulter have in common is that of what I call the liminal zone. The space between. Often referred to as a transitional and transformative space which is a space of possibilities. A threshold toward change, change in our physical world such as the twilight zone, or for example, the zone between the earth and the space beyond. It can also be viewed as a threshold of the mind between the familiar and the unknown, the untraversed, sometimes rocky terrain that is crossed when heading toward an unknown future. The unknown can evoke feelings of trepidation and fear; however, it can also lead toward our growth zone in which there are new possibilities for our future.

I also see a commonality between Rothko and Boulter as both these artist’s work could be described as sublime for different reasons. When I use the word sublime as a reference to art, I am using it in the sense that light in the landscape can invoke the spiritual through a sense of awe, laced with beauty and terror of the internal psyche. Not the kind of terror that literally has me shaking at the knees, but the kind that is imbued with the magnanimous power of nature in all of it’s beauty and terror.

Rothko’s work is well documented with reference to the spiritual and the sublime, however its power was in the mind, not in reference to our external world through landscape form. Boulter’s work references the landscape of both the internal and external world, the invisible is embedded in the visible representation of the external world.

The Wikipedia article Art and Emotion references Noy & Noy-Sharav as saying ‘the optimal visual artwork creates… "meta-emotions." These are multiple emotions that are triggered at the same time…’ They also

‘claim that art is the most potent form of emotional communication. They cite examples of people being able to listen to and dance to music for hours without getting tired and literature being able to take people to far away, imagined lands inside their heads. Art forms give humans a higher satisfaction in emotional release than simply managing emotions on their own. Art allows people to have a cathartic release of pent-up emotions either by creating work or by witnessing and pseudo-experiencing what they see in front of them. Instead of being passive recipients of actions and images, art is intended for people to challenge themselves and work through the emotions they see presented in the artistic message’.

An exploration of the emotive as a creator of art, and how to intensify that experience, or layer that emotion is of interest to me. This string of ideas highlights to me how the experience of art can trigger emotions in the viewer. The magnetic pull of a beautiful painting can stay with me long after it was experienced, like Boulter’s work did, as can the immersive experiential artwork, such as the largely projected heads by Struth which were quite disturbing in a confronting sort of reality, before it eventually became comfortable as my friend and I positioned ourselves as the voyeurs and critics involved in a cerebral activity, only to be confronted finally with our own humanity.

At the Biennale of the Everyday, Ann Veronica Janssens used the boundaries of the actual space by filling two gallery rooms with fog alone, and screens place strategically in front of the windows that let light filter in the sides from behind. Walking through this exhibit transported me into a place beyond thought, a place of wonder, of light-filled ambiguity, a beautiful denseness and lightness at the same time, a sense of entering a transitional space, the veil to another world beyond consciousness where we all fade into grey ethereal matter.

Jacki Fleet

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Michaye Boulter for the kind use of her images in this article.

Michaye is now represented by Bett Gallery in Hobart, Tasmania. She will be having an exhibition in October 2021.

About the Creator

jacki fleet

I am an artist. A painter, designer and creator who likes to write. I live in the Northern Territory of Australia. Writing is something I enjoy, usually for myself. I decided it's time to start sharing.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.