Sticky Labels: A Short Story

An analysis of mental health in creative media

This short story and analysis was originally written for my University dissertation. As I’ve now graduated, I wanted to do more with this piece than letting it sit idle in my writing folder. I am not an expert on mental health; reasoning for details included in the story can be found through the analysis underneath. Everyone’s experience is different, and I in no way mean to stereotype or insult a person who suffers from any sort of mental health condition.

...

Think about the phrase ‘mental health.’ What comes to mind? It could remind you of a friend, it could elicit sympathy, or perhaps, like my father, you could think the whole thing to be bollocks. For me, it meant disaster. It meant pain and isolation. I grew up surrounded by the propaganda — the movies where the bad guys one motive was the voices that whispered to him, the criminals who were branded as unstable on the news, the shock of seeing how fast it could destroy a life. To be ill mentally was to surrender oneself as the villain. And when the voices started in my own head, that’s exactly what I did. I gave up all hope for a normal life.

I was 9 years old when I first learned about mental health. It was late, around 10:30 pm on a Saturday. The summer heat had left me restless, so I crept from my bedroom to the kitchen for a glass of water, terrified of being caught awake past my bedtime.

Dad saw me, but he wasn’t angry. He was lounging on the couch, a cold bottle of beer held lazily, slipping from his fingers, his eyelids sliding closed. ‘Emma,’ he’d said, playfully stern, ‘you’re supposed to be in bed.’

‘I’m sorry. It’s too hot, I can’t sleep.’

He called me over. I sat down on the opposite end, head rested against the cushions, feet draped across his lap. Mum had fallen asleep on the smaller couch. She was snoring lightly, curled into a ball, her knees tucked under her arms. The fan whirled gently, blowing at the hairs straying from my ponytail. It was peaceful.

The news was on the TV. Dad wasn’t paying much attention, more interested in swirling the last of the beer in his bottle from side to side, taking sips until it was empty. He placed the bottle on the table and sank further into his seat.

‘Man arrested in correlation with Target Shooting in Houston, Texas. Suspect said to be suffering from paranoid schizophrenia and claims to have been ‘defending himself’ from ‘the agents’ that were following him. He has been taken into police custody for the time being.’

Paranoid schizophrenia. I hadn’t a clue what it meant, but the phrase stuck with me.

‘Why did he shoot those people, Daddy?’ I asked, with all the wonder of childhood innocence.

‘He wasn’t well. People who are poorly in the head do bad things.’

‘But why?’

‘Something inside of them isn’t right.’ He shifted in his seat, sat upright. He patted my leg twice, reassuringly. ‘Don’t you worry about it. You’re a good girl, you don’t need to worry about things like that.’

I had drifted off sometime after the conversation and woke up the next morning cuddled into my pillows. That conversation probably meant nothing to him, but to me it was an understanding. Mental illness was evil. People with mental illness do bad things, devastating things, and have no control over it. To my innocence, this was gospel.

...

I’d never seen my Dad cry before.

I was 13, sat on my aunt’s couch, watching my younger cousins play with their Lego blocks on the coffee table. The atmosphere was tight. I was overly aware of how loud my breathing was, how awkward I must have looked, with my legs crossed over each other, how uncomfortable I was, yet too anxious to move, not wanting to draw attention to myself. It was bizarre, really. No one was the slightest bit bothered about how I looked. We were all at the house, but only us kids were in the lounge. The adults were all stood around the dining table, pacing back and forth, restless. Helpless.

We knew Nana didn’t have long left, but it still came as a shock. We were told she had at least a few months left, but an emergency ambulance ride in the night had taken a turn for the worse. She hadn’t even made it to the hospital before she passed away.

We were in mourning before we’d had the chance to accept she was ill. It hit us all hard. The kids didn’t really understand; they were excited that they got to spend the day together, and every so often the youngest would ask my aunty, ‘Where has Nanny gone? Is she on holiday?’ My aunt would squeeze her tight, stroke her hair, and hold back tears. My Dad would walk away.

Dad never really recovered. I’d heard Mum ask him if he wanted grief counseling, but he didn’t believe in that sort of thing. ‘It’s a waste of our money. I’ll be fine,’ he would say, and Mum would sigh, and go back to whatever it was she was doing.

He wasn’t fine, not really, but he kept a stiff upper lip in front of us. He was from a generation who didn’t like to talk about things, and I’d learned to stop asking a long time ago.

...

I went to a party when I was 15. I told Mum it was a sleepover for my best friend, Alicia’s, birthday, which wasn’t exactly a lie. I knew there’d be booze, maybe a few cans of beer, and a bottle of wine that she’d conned her older sister out of. I wasn’t expecting her parents to be away for the weekend, nor was I expecting the large oak dining table to be pushed against the wall, covered from end to end with bottles, ranging from Smirnoff Ice to Absinthe. Some of our other friends were already there, changing into different clothes, struggling to talk over the music that was blasting from a laptop perched on the couch.

Alicia swept me into a hug when she saw me standing awkwardly in the doorway.

‘Thank God you’re here!’ She squealed. I could already smell the lightest hints of alcohol wafting from her lips. ‘You’ve only got an hour to get ready. Throw your bag in my room, I’ve cleared a space on the floor for your sleeping bag.’

She was gone before I could say anything, fluttering about the room, straightening out the furniture and fussing with the decorations. She had the sense to move anything valuable out of harm's way.

I took myself up to her room, threw my stuff on the ground, sank to my knees, and took a deep breath. I was just nervous, I’d told myself, and it was perfectly normal to be nervous. I got changed in private to give myself some breathing room. My shirt was a little too tight around my waist, when I sat down I could feel it press against my stomach. I tried not to be self-conscious, but I felt exposed. There wasn’t much to hide behind, but there was a strict ‘no baggy clothes’ policy. Alicia said baggy clothes were for children, and because she was 15 now, we needed to act like adults. I wasn’t ready to be an adult, but that wasn’t a hill I was willing to die on.

I grabbed my makeup pouch and ran downstairs before I could talk myself out of doing so. I would have hidden until someone found me if I had my own way. Portable mirrors were placed in a haphazard line across the floor. Most of the other girls had already finished getting ready, which was good. They were too distracted to focus on me. I didn’t like people watching me. My eyeliner came out a bit wonky, but it wasn’t terrible. I looked nice, I let myself think.

Alicia burst into the room at last, full of energy, shouting about how we were going to ‘get absolutely wrecked!’ She was carrying a tray with about 7 disposable shot glasses, each filled to the brim with what I could only assume was vodka.

‘Pre-drinks, ladies!’ She passed the tray around. I stared into the sticky, clear liquid, tried to swallow the discomfort rising in my chest.

‘Three, two, one!’

Everyone knocked their glass back at the same time. My throat burned. I wanted to cough, but I grit my teeth, tried to ignore the discomfort, not wanting to be the weirdo who had never taken a shot of straight booze. My stomach felt warm. I felt lighter almost immediately.

The music was turned up louder, the mirrors were folded away to somewhere they wouldn’t smash. More people started to arrive, most of which I knew from school, but some people brought friends with them. I drank anything that was passed to me, as fast as I physically could. The room was packed, I had barely enough room to raise my arms without hitting someone else. Sweat dripped from my forehead, streaking my foundation, my mascara smearing around my eyelids. My head pounded alongside the bass of the music, blurry and loose on my feet, I stumbled, falling against whoever was in front of me. He held me upright, helped me to the kitchen door, where people were stood on the patio, smoking, and chatting idly.

‘Are you okay?’ His hand was on my arm, cold and comforting. A breeze swept by. I closed my eyes, felt it sweep against my face. I felt sick.

I sank to the floor. He put an arm around me, rubbed circles with his fingers. I could hear him speaking, but I couldn’t make out the words. My body was numb.

Alicia came outside. She began shouting, I wasn’t sure why. The boy shouted back. I swallowed the vomit that tried to claw its way up my throat. The memories were blurry after that.

Black and then the bag I’d left in Alicia’s room was thrown at me and then black and then the boy had his arms around me and was walking me to the front door and then black, but I could feel the vibrations of a car — a taxi, maybe? — and then I was outside my parents’ house, sobbing into this stranger’s arms. He helped me inside, my parents thanked him, and he came in for a coffee. I lay with my head in my Mum’s lap. She stroked my hair, called me a silly girl, but she was happy that I was safe. They gave the boy — Michael — some money for a taxi, and he left me a piece of paper with his name and mobile number, in case I wanted to message him.

Dad stayed quiet the whole time. He watched as I sipped on water, my Mum gently cleaning my face with a make-up wipe. He went to bed on his own. Mum stayed with me until I sobered up a bit. I couldn’t stop crying. My heart sank as I began to remember who Michael really was, why Alicia was so upset. In her eyes, I’d tried to pull the guy she fancied, a crime greater than manslaughter in the eyes of a teenager. That was the end of my happy school days.

By Monday morning, I was branded a whore. Rumours fluttered by, hovered around my head, like flies circling garbage. Michael was the only person who stood by me, but that only made things worse. He felt sorry for me, but he didn’t lose any friends. Alicia still batted her eyelashes every chance she got. No one called him a slut. No one turned against him.

Still, I appreciated his company. He was sympathetic, though there was a thin line between sympathy and pity. He was the only one who cared when I stopped showing up for class.

‘You can’t let this ruin your future,’ he’d said, as though he knew what was best for me. Perhaps if he had, he would have stood up for me when the whispers had started. Perhaps, if he had challenged the accusations harder, I wouldn’t have had to skip double Maths for fear of being ridiculed, for having my hair snipped, my bag torn, and my self-esteem ripped from inside of me, shattered upon the floor.

It was the loneliest I had ever felt. I was kept awake by shallow breaths, fearing the next moment I’d have to walk through the front gates. I stopped eating breakfast, could barely find the energy to brush my hair. I never wore it tied up. Some days, my worst days, I couldn’t brush my teeth. I chewed gum on the way to school to mask the scent, spent more time spraying deodorant than showering. Homework lay forgotten at the bottom of my satchel, crumpled and water-stained. I didn’t see the point in trying. No one wanted me around, and I didn’t have the drive to fight it.

Mum tried to hold some sort of intervention. She looked so awfully tired. I was too embarrassed to tell her I didn’t have friends anymore. She told me Alicia was being a bad influence.

‘I don’t want you hanging around with her anymore,’ she’d said, stern and final. I held back a few tears. ‘We’re going to watch you do your homework. No phone until it’s all done.’

I didn’t argue with her. It’s not like I had anyone to text, anyway.

Things began to pick up, in an academic sense. Mum thought I was your typical lazy teenager, so she put in some extra work to help me. Dad helped too, wherever he could. He was still putting on the ‘tough man’ act, but every now and then I heard him crying at night. It was an unspoken rule that we didn’t talk about it.

Looking back, I’m grateful for Mum’s help. School was still a nightmare, but I was getting good grades, and that meant a good future, apparently. I passed my GCSEs almost effortlessly, and when I was allowed to choose where to take my A-levels, I purposefully chose a local college instead of going to sixth form. A fresh start: a chance to reclaim myself for who I was, rather than who I was perceived to be.

And I tried. I really fucking tried. I made a few friends in my History class, which turned out to be really bloody difficult. We started a weekly study group in the college library. There were four of us; a shy girl, Sarah, who stuttered over her words but told the funniest, crudest jokes I’d ever heard; a loud boy named Oliver, whose voice carried with a whisper; a girl called Jess, who wasn’t the smartest girl, but had a heart so kind she could quell your worries with a smile; and myself, who found it hard to trust any of them.

The anxiety never went away. If anything, it became worse. Every word I said was a chance to be criticised, every move I made could lead me in the wrong direction. I spent so much of my time overthinking. Is my breathing too loud? Am I sitting in a weird position? Is what I’m wearing too plain, or not plain enough? It was exhausting. I wanted to vomit every time my name was called for the register.

‘You okay?’ Jess had whispered to me. She’d pulled me aside in the lunch hall, just before our next class started. I hadn’t eaten any of my food, and I guess she’d noticed.

‘No, yeah, I’m good.’ I tried an easygoing smile, the same kind she could pull off without a thought. It looked like more of a grimace. ‘Are you?’

Her face scrunched up, she wasn’t good at hiding what she was feeling. Far too honest for her own good. ‘Well… if there is anything, you can tell me, okay?’

‘Okay,’ I said, but we both knew I was lying. I couldn’t tell her what was wrong. I couldn’t tell her about Alicia or Michael. I couldn’t face being called a creep again. I couldn’t have her think I was crazy.

I kept up appearances as best as I could after that, but it was beginning to get too much. I only ever went outside to go to college. I spent my free days recovering from the mental exhaustion of pretending to be happy. I was on the tip of the iceberg, straining to keep myself afloat. And then I fell.

...

I was 17 when the voices started. I took comfort in them because they made me feel less alone. They started as nothing more than a niggling, a reminder that what I was doing was wrong, somehow. They helped me, kept me in check to make sure I didn’t mess anything up, like I always did. Some were kinder than others. On my college days, they reminded me to brush my hair, because no one would be friends with an unkempt hag. I brushed until my scalp hurt, pulled my hair back so tight, my head was throbbing from the strain. They reminded me to smile, to always say yes, to put everyone else before myself, because they were more important. They didn’t need me dragging them down.

Others were scathing. They kept me bound to my bed. They stopped me from sleeping, stopped me from showering and eating. They looked at the pile of papers on my desk and told me not to bother, because it wouldn’t make a difference, because I didn’t deserve success. I needed to better myself, not academically, but personally. I needed to learn how to hide what a fucking disaster I was, or everyone would leave me.

It didn’t take long for my parents to notice. Dad walked into my room without a warning and threw my curtains open. The light stung. I hadn’t slept that night; I hadn’t slept properly for a few nights.

He ran his hands along the pile of unfinished assignments, patted them twice, and sighed, ‘I thought we were past this.’

I didn’t know what to say. They said I’d never get past this. They talked over each other, mumbling and shouting. I buried further into my pillow. Dad sat awkwardly next to where my legs were stretched out beneath my duvet.

‘What can we do to help? You can talk to us.’ But I couldn’t talk to them, and they couldn’t help, because once they knew the real me, they’d know I was a bad person. No one wants a bad person for a daughter.

‘I’m just tired.’ It wasn’t a lie, but my generic excuse. My eyes were swollen, puffy and purple rimmed. He couldn’t dispute it, I knew that. A part of me wished he would.

He didn’t know what to do. I wouldn’t have, either, if roles were switched. ‘Well,’ he paused, shifted a little, ‘have a bit of a nap, freshen up, and then maybe the three of us could go out for a coffee? Some sunlight might do you good.’

‘Sure, sounds nice.’ It wasn’t a suggestion, I knew that.

He smiled, a genuine, loving smile. ‘I’ll wake you up in two hours, get some rest.’

The sunlight didn’t do me good. I wasn’t present at the café. I picked at the scone Dad bought me, tried to nod in all the right places whilst Mum talked, but my mind was in a different place. I felt guilty, that they wouldn’t love me if they knew the truth. My mind chipped in, told me no one would love me, not if they really knew me. They told me to watch what I did, to not slip up, so I paid attention. And when they told me to hurt myself, to punish and reform, I didn’t hesitate.

No one knew, not for a very long time, but one night I was clumsy. That night, on a stomach empty aside from a few scone bites and a cola, I took it too far. A scar too deep in the kitchen, a mess I couldn’t clean before Mum found me. She screamed such a heart-aching scream, the last thing I heard before lightheadedness took its hold. The rest of the night passed in a blur. A stream of ambulance lights and beeping machines, unfamiliar faces, needles, and IVs.

When I woke up the next day, I was sweating buckets. My mouth was so dry I couldn’t swallow. I tried to sit up but felt the tug of an IV line in my arm. I didn’t move much after that, they made me nervous.

Mum was sleeping in an armchair beside me but stirred when she heard me moving. She rushed to my bedside, took hold of my non-IV hand, and gave it a tight squeeze.

‘I was so worried. Oh, darling, I was so worried.’

She filled me in on what I’d missed, between her tears of joy and flurries of concern. Everyone was worried about my mental health. I was classed as a danger to myself and no one knew why. Seeing my Mum in tears, my arm bandaged up, I knew I couldn’t protect myself any longer. I told her how I’d been feeling, that I didn’t want her to hate me, that I was just as scared as she was. She hugged me for a long time after that, until the day doctors did their morning rounds. She encouraged me to speak up, and her voice echoed louder than the others screaming at me to stop. When asked why I hurt myself, I told the truth. I told the doctor that I didn’t want to, but I had to, because they told me to.

I was later diagnosed with Paranoid Schizophrenia and was admitted to a psychiatric ward.

...

My doctor is nice. She helps me separate the voices from my own thoughts. When she told me I wasn’t a freak, that I wasn’t evil, and I cried, she did not judge me. She didn’t turn away from my vulnerability but welcomed it as a way to heal.

Jess visits me at the ward when she can. Sometimes Oliver and Sarah come with her too, but Jess visits the most. She brings me digestives and distracts me with college gossip, and in those moments I am just a teenager, and we are no more than two girls hanging out, as normal.

When Mum and Dad visit we’re allowed to take walks, and that’s nice. I can tell Dad doesn’t really understand any of what’s going on, but he hugs me when he sees me, and that’s enough.

I don’t get along with the medication, but from what I’ve heard, not many people here like it. It makes me a dribbling mess, lethargic and untuned from my surroundings. But it helps me sleep, and I’ll always be grateful for that.

I’ll be able to leave here, one day. My college agreed to let me finish my course when I’m ready. I focus on that as a goal. It helps me imagine the future in a kinder light. I’m still learning how to be kinder to myself, how to challenge the voices I hear, rather than take them as gospel. Slowly, I’m convincing myself that I was never the villain in the first place.

This happy ending isn’t traditional. I am not cured, I am learning how to cope. I can be as normal as anyone’s definition of normalcy, eventually, because one day this will be my normal. And that’s okay.

...

Analysis & Research

Mental health is something that we are all aware of, but not necessarily educated on. There’s a lot of support for conditions such as anxiety and depression, which is a huge step forward for the recognition of mental health, but sadly, some other conditions still suffer from a plethora of stigma. Conditions such as psychosis, schizophrenia, DID, etc. are often trivialised by the entertainment industry, being used solely for shock factor, or written as backstory for the antagonist, their illness making them ‘evil’. These representations, particularly in the horror genre, are extremely damaging to people who suffer from these conditions. They spread misinformation and promote the idea that people suffering from mental illness are inherently dangerous, which can hurt, demoralise, and ostracise people with real conditions.

The aim for my creative piece was to create a story surrounding a realistic character who begins to suffer from schizophrenia but doesn’t initially realise. The character, Emma, views people with mental illness as ‘the bad guys’ and is afraid that revealing her struggles will ostracise her from her friends and family. I wanted the story to end in a positive way, but not in a traditionally happy way. Emma is not cured but learns to accept her condition and move forward to find ways to cope with this new part of her life. I carefully researched the topic, aware that it was one to be treated with respect. I knew that as I was someone without a psychiatric diagnosis that there would be a chance I could never accurately portray what having one was like, but my intention was to show that through proper research and care, anyone could include a character with mental illness in their work in a respectful manner.

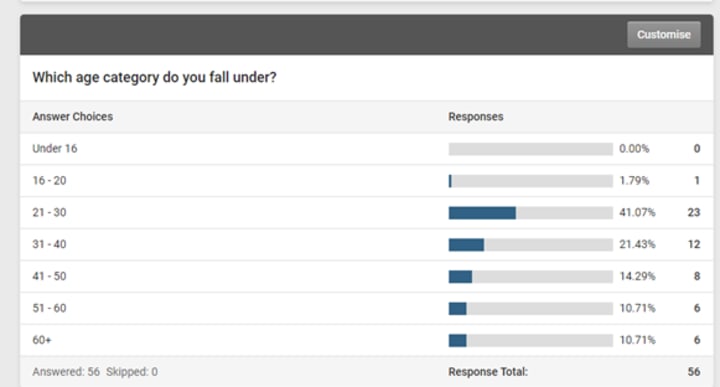

To begin my research, I sought the opinions of the public through a survey, conducted through SmartSurvey.com. Of the 56 people surveyed, 69.64% were female-identifying, 25% were male-identifying, 1.79% were transgender and 3.57% were nonbinary (Appendix. 1). There was a strong variance in ages, with 42.86% being aged between 16 to 30 years of age, and 46.43% being aged between 31 to 60 years of age (Appendix 2.). When asked what their favourite genre of fiction was, the two most popular answers were fantasy (25%) and crime (21.43%), whilst the least popular answers were horror (30.36%) and western (26.79%) (Appendix 3.).

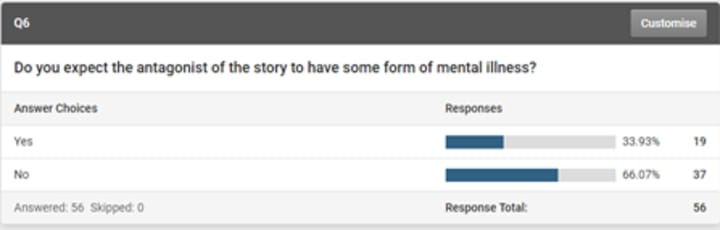

When asked if they believed mental illness was respectfully represented in fiction, an overwhelming number of participants said no, often giving reason that mental health was often given to ‘the bad guy’ which is a harmful stereotype. What surprised me was that despite this commonly thought opinion, when asked if they expected the antagonist of the story to have some form of mental illness, 66.7% said no (Appendix 4), but when asked if the antagonist being mentally ill made them more sympathetic, 55.36% said that yes, it did. This surprised me and went against my initial hypothesis. Originally, I had suspected that an antagonist’s mental illness wouldn’t have elicited a more sympathetic response, but I was pleasantly surprised to find that there was empathy out there for mental illness. However, the issue still remained. Many participants included examples of media they believed was harmful in their representations, and so I moved my research into looking into these highlighted areas.

A film with an extremely harmful representation of mental illness is the film Split by M. Night Shyamalan. It was praised by moviegoers familiar with the directors’ work, as he is well known for creating unusual storylines that incite intrigue and mystery. However, Split came under fire by medical professionals who have further stated that not only is the representation of Dissociative Identity Disorder completely wrong, but harmful to people with the disorder. ‘The movie may imply that someone with DID could be violent, but experts say those people are more likely to hurt themselves than others.’ (Split: Why Mental Health Experts Are Critical of the Movie, 2014) The film shows the main character kidnapping three young teenage girls, seemingly without any form of motivation, with his only excuse being that he has DID, and one of his personalities is sadistic. People with DID are highly unlikely to cause harm to others and are more likely to become a harm to themselves, and poor representation such as this can cause stigma, and potentially cause people who suffer from DID symptoms to avoid treatment in case they are labelled as such by other people. Labels stick, especially when it comes to psychiatric conditions.

A study done called the Rosenhan Experiment proved this by having Rosenhan himself, along with several other mentally healthy associates become admitted into a psychiatric hospital by faking common mental health symptoms. Whilst they were admitted, they returned to their usual behaviour, and found out first-hand how hard it was to be discharged from such an institute. The labels stuck to these associates, despite the diagnosis being completely false (Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). Now, imagine what that is like for people where the diagnosis is correct, or perhaps, initially misdiagnosed, later to be found they’re suffering from a different condition. Are we expected to believe the former label disappears in the minds of their friends, family, and future doctors? Films with poor representation, such as Split, help to keep labels, often unfavourable, stamped upon the heads of those with psychiatric conditions. People with very little education when it comes to mental illness may view media of this sort and believe it to be true — why else would it be allowed to be shown in cinemas nationally? Unfortunately, Split is not the outlier when it comes to films about mental health, there are hundreds of examples of trivialised representation that promote violence, insanity, lack of empathy and selfishness in correlation with mental illness which often results in serial murder, rape, and enjoyment of violence and abuse behaviour. (Boll, 2015)

I didn’t want to make the same mistakes as the directors and writers who so poorly misrepresented mental illness as a whole. The novel, ‘The Shock of the Fall’ by Nathan Filer, was a marvelous introduction to a work of fiction that realistically represented the issues it put forth. I looked into the author's background and found another nonfiction book written by him wherein he interviewed various people with different forms of schizophrenia. Filer’s work and style of presenting information heavily influenced my own work, in terms of style and tone. The first-person point of view made the narrative more empathetic, helping the reader understand the emotions of the characters despite never having been in those specific scenarios. A case that stood out to me in his nonfiction work was the section that told the story of a woman with paranoid schizophrenia, who believed that she was responsible for every bad thing that happened on the news. She became paranoid that she was on the run, and it began to take an extreme toll on both her personal and professional life. This particularly intrigued me because it’s a side of schizophrenia that is very often not explored. She was not a violent woman, she didn’t appear ‘crazy’ or ‘deluded’ to the people around her. On the outside, she was completely normal. This was a main factor that I wanted to feature in my work. Emma’s parents notice that something is wrong because they are directly linked to her personal bubble by being in the same house as her, but the others in her life don’t show concern, because they don’t see it. Her friend, Jess, tries to pry and is obviously concerned when Emma begins to show symptoms outside of her home bubble, but again, no intervention takes place until a drastic event explicitly reveals the severity of the situation. I wanted to link this event back to the stigma previously mentioned by films such as Split by showing how unlikely it is for someone with a mental illness to hurt others, as it’s more likely that they harm themselves.

Other non-fiction books such as Agnes’ Jacket by Gail A. Hornstein gave me a further look into the psychiatric ward side of things, where I learned about the side effects of medication, how people don’t necessarily recover from their conditions, but learn how to cope with them and perhaps use them to an advantage. Virginia Woolfe is used as an example, where the characters in her stories were often born from personal experience. A quote from Hornstein’s work stuck out to me in particular, ‘More broadly, their research demonstrates that it isn’t trauma itself that makes someone a psychiatric patient; it’s the nature of the trauma, when it occurs, how long it lasts, whether it’s denied by others, and whether the person gets help.’ This was where the initial development of my story began. Emma denies to herself that she has a problem — she is told by her father that bad people are mentally ill, she doesn’t want to ostracise herself further, and she doesn’t want her family to hate her or disown for being ‘evil’, even though it is out of her control.

The subject of mental health is one that is close to home for many, an anomaly to others, and above all something that even professionals are still trying to learn and understand. In some of the earliest editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorders homosexuality was classed as a mental illness (Carr and Spandler, 2019), which is a fact that may shock many people, particularly those younger in age, where homosexuality is celebrated and accepted. Perhaps in the future, there will be more definitions, changed definitions or even less definitions — what’s important right now is how we view them, and how we portray them to each other; with care, insight, and realism. With a change of audience expectations, we can erase the stereotype of negativity, which in return can help not only the people with such conditions, but the doctors, nurses, psychiatrics, and charities that work so tirelessly to help people understand. In retrospect, the work I produced could be viewed as nothing more than superficial. I have no personal experience with schizophrenia, so how would I be able to produce work with any amount of substance? Perhaps writers should take a different approach — ghostwriting for someone else who did have experience or considering that if they didn’t have the time to put research in, they should maybe consider writing about something else.

...

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Bibliography

1. Association for Psychological Science — APS. 2014. Stigma as a Barrier to Mental Health Care. [online] Available at: <https://www.psychologicalscience.org/news/releases/stigma-as-a-barrier-to-mental-health-care.html> [Accessed 18 May 2021].

2. Bhat, P. S., Pardal, P. K., & Diwakar, M. (2011). Self-harm by severe glossal injury in schizophrenia. Industrial psychiatry journal, 20(2), 134–135. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.102524

3. Boll, J., 2015. 6 Popular Movies that Got Mental Illness Wrong. [online] Resources To Recover. Available at: <https://www.rtor.org/2015/10/27/6-movies/> [Accessed 18 May 2021].

4. Carr, S. and Spandler, H., 2019. Hidden from history? A brief modern history of the psychiatric “treatment” of lesbian and bisexual women in England. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(4), pp.289–290.

5. Drinkaware.co.uk. 2021. [online] Available at: <https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/facts/health-effects-of-alcohol/mental-health/alcohol-and-mental-health> [Accessed 18 May 2021].

6. Filer, N., 2013. The Shock of the Fall. Harper Collins.

7. Filer, N., 2019. This Book Will Change Your Mind About Mental Health: A journey into the heartland of psychiatry. Faber & Faber.

8. Health Essentials from Cleveland Clinic. 2018. 5 Reasons You Shouldn’t Ignore Your Mental Health. [online] Available at: <https://health.clevelandclinic.org/5-reasons-you-shouldnt-ignore-your-mental-health-2/)> [Accessed 18 May 2021].

9. Healthline. 2014. Split: Why Mental Health Experts Are Critical of the Movie. [online] Available at: <https://www.healthline.com/health-news/movie-split-harms-people-with-dissociative-identity-disorder> [Accessed 18 May 2021].

10. HelpGuide.org. 2021. Schizophrenia Symptoms and Coping Tips — HelpGuide.org. [online] Available at: <https://www.helpguide.org/articles/mental-disorders/schizophrenia-signs-and-symptoms.htm#:~:text=There%20are%20five%20types%20of,both%20in%20pattern%20and%20severity.)> [Accessed 18 May 2021].

11. Hornstein, G., 2017. Agness Jacket — a psychologists search for the meanings of madnessrevised a. Routledge.

12. nhs.uk. 2021. Treatment — Schizophrenia. [online] Available at: <https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/schizophrenia/treatment/> [Accessed 18 May 2021].

13. Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179(4070), 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.179.4070.250

14. Split. 2017. [DVD] Directed by M. Shyamalan.

15. Stuart H. Media portrayal of mental illness and its treatments: what effect does it have on people with mental illness? CNS Drugs. 2006;20(2):99–106. doi: 10.2165/00023210–200620020–00002. PMID: 16478286.

16. What are the signs and symptoms of an anxiety disorder?. 2021. What are the signs and symptoms of an anxiety disorder?. [online] Available at: <https://www.rethink.org/advice-and-information/about-mental-illness/learn-more-about-conditions/anxiety-disorders/> [Accessed 18 May 2021].

About the Creator

Jade Hadfield

A writer by both profession and passion. Sharing my stories about mental health, and my journey to becoming a better writer.

Facebook: @jfhadfieldwriter

Instagram: @jfhadfield

Twitter: @jfhadfield

Fiverr: https://www.fiverr.com/jadehadfield

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.