From Cat’s Cradle to Sculpture: The Path to a Peaceful Being

A lace maker's story

I can date my love of creating through thread-making way back to the playground game of Cat’s Cradle.

The game, played by two or more, involves nothing more than taking a piece of string about 40 inches long and winding it into an open formation – the Cat’s Cradle - around both hands. The formation is then taken, and changed in the process, by the next player. The game continues by passing while changing the intricate shapes, needing concentration and collaboration. The game provides both focus and fun.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v7LlAt5DmQs

I would never have equated this child’s game with sculpting. But it was discovering the work of British sculptor Barbara Hepworth that formed the link in my mind.

Dame Barbara Hepworth moved to Cornwall, England, in 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War. Her relocation was driven both by the desire for refuge from the threat of chaos and destruction, and the draw of the magical English county that had inspired so many artists before her, inspired by the light and the landscape. But during her time in that land, in her cave of a studio in St Ives, it was the sea that inspired her stunningly beautiful Wave sculptures.

I first encountered these at the Tate St Ives. The pure white, cast concrete gallery had been built between 1988 and 1993, on the site of a former gasworks, overlooking the glorious Porthmeor Beach. It was during this time the Tate also became the guardian of the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Studio.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hgkgbzPfvG8&t=13s

The sculpture I saw on display at the Tate gallery was Pelagos (Greek for sea), a sleek, curved plane of elm wood pierced through with lengths of string. I was transfixed by the almost feminine, abstract form, which seemed to give off a spiritual aura. But I was also totally puzzled by the threads of string that had been incorporated into the wood.

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hepworth-pelagos-t00699

My first thought was that it was a representation of sound; it did look a little like Apollo's lyre. The string, I discovered, was a motif that appeared in many of her pieces, and it was only later I learned that Hepworth described the string as representative of ‘the tension I felt between myself and the sea, the wind or the hills’. As soon as I read this I realised I had been focusing on the visual impact of the sculptures, the beauty and elegance of its form, its apparent calmness. What I hadn’t noticed, until I read Hepworth’s description, was that tension. Nor had I been aware, when I looked at the pieces, of how I was feeling that same tension in my gut. It was this understanding of Hepworth's sculptures that awakened my realisation that, over the years, a serious disconnect had developed and grown between my mind and my feeling centre. And my intuition.

I had always been a highly intuitive child, and this had followed me into adulthood in both my creative work and my practice as a mental health therapist. I would paint or write less with my intellect and more with intuition and emotion. I would listen to a client’s pain and confusion with my heart as much as my head. But somewhere along the line, I had lost this ability, or rather I hadn’t lost the ability itself, but I had lost the awareness of that ability. I had lost touch with a part of myself. And I no longer felt 'whole'.

'Not a problem,' I thought. 'This is what you're trained for. You have hundreds and hundreds of hours of experience helping others find their way out of the minotaur's cave. Just practice what you preach. Simple!'

How wrong was I to believe it would be that easy? The reality proved that the harder I tried to find my way back to my self, that more I seemed to fail. And each perceived failure brought with it more frustration. And grief. But I didn't give up. I changed my diet. I went down the gym. I read texts on spiritual paths. But it seemed the more effort I put into getting back in touch with the core of my being, the further I seemed to travel away from it. As the weeks and months went on, I found that the frustration and grief were boring their way into all corners of my life, permeating my day-to-day decisions, my reactions to friends and family. My self-esteem took a daily pummelling. I felt adrift and isolated. And also fearful. I knew from my mother that more than one member of my family had experienced poor mental health.

It was at my lowest point, feeling a deep need for connection, that I began to research my family history. I knew my paternal grandmother had committed suicide when my father was barely out of his teens. This resulted in a rift with his father that had never healed, and so my connection with my roots were severed on that side, cutting me off from aunts, uncles and cousins, as well as grandparents. My mother was illegitimate, and spent the first years of her life in an orphanage. She was adopted when she was five, and times being what they were back then, never knew her birth family. Her adoptive mother's mental health was also irrevocably damaged, partly as a result of the war: she lived in an area that was heavily bombed in the 1940s. It resulted in a psychotic breakdown and she was admitted to what they called, in those days, a lunatic asylum, where she died two years later. I had been told these stories when I was still a young child, but I never learnt of my family beyond this. In my own dark days, these stories came back to me like both a warning and an inspiration. I decided I needed to know more about my ancestry. To know them more as people, rather than tragedies.

Finding information on my mother's side meant real detective work. Adoption from the old orphanages in the early part of the 20th century, with their secrecy and paper files, plus the lack of access to census data which needs 100 years to pass before they became available, made tracking this family lineage very tricky, and work is ongoing. On my father's side, however, I made a discovery that became the beginning of my way back to what I had begun to refer to as My Old Self.

I contacted the General Register Office (GRO) for copies of my paternal grandmother's and grandfather's birth, marriage and death certificates, and as I began piecing together the key pieces of their lives, my own healing began.

My greatest discovery was:

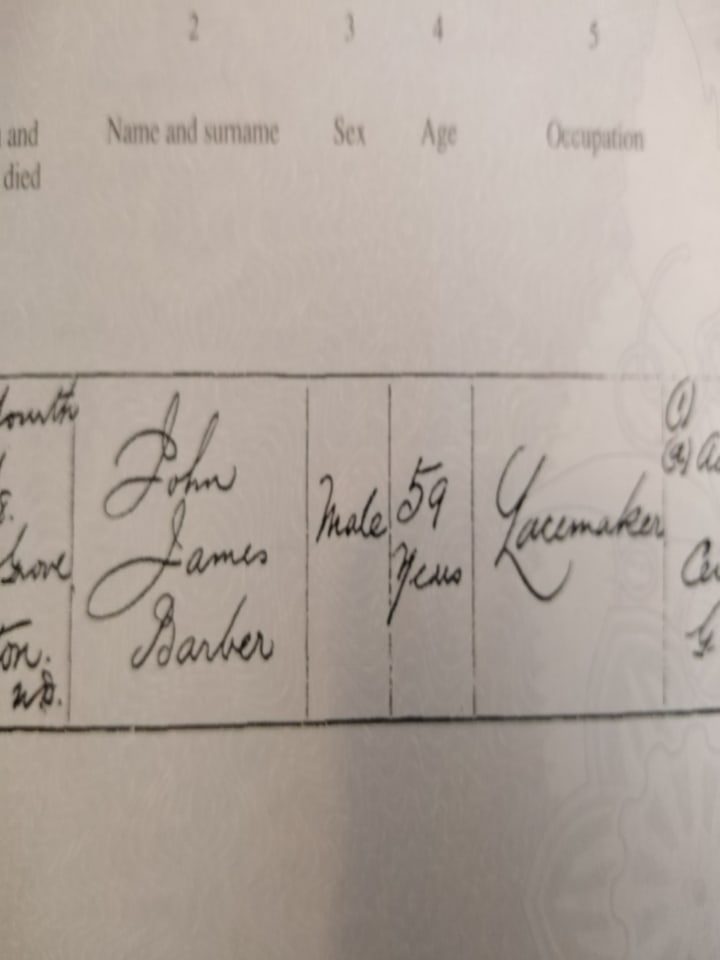

WE WERE LACE MAKERS!

There is no time for the whole story here. In fact, the whole story has yet to be uncovered. But the nub of it is that my father's maternal grandfather, John James Barber, was an early 19th century lace maker in Somerset, England. With the coming of the industrial revolution, the lace making industry became mechanised, and work for the traditional, skilled lace makers began to die out. My great-grandfather therefore upped and moved his family to Beeston in the Nottingham area of the Midlands, where he became a 'twisthand'. A twisthand was a lace machine worker and the role became highly valued. Twisthands even had their own bar down the local pub.

http://www.beeston-notts.co.uk/industry_lace.shtml

It was there that my great-grandfather's daughter - my grandmother - met my grandfather. His father was also a twisthand and was good friends with John James Barber.

As my detective work continued, I discovered that lace making had been what had brought my family together. Without the lace making industry, I would probably not even exist! Quite a sobering thought.

Discovering that my roots lay in the craft of lace making was a turning point for me, and I wanted to know more. I wanted to get in touch with my roots, with the people I never knew. People who died years before I was born, but had lived their lives in such a time of tumult. I wanted to know what it felt like to hold the bobbins and thread. To follow centuries old patterns and bring them to life. I wanted to know what it felt like to be a lace maker.

I wish I could tell you that I'm there. But I'm not yet. My fingers are clumsy, and the close work challenges my eyesight. However, I am following those traditional lace makers' paths. I am sitting and patiently laying and weaving, taking in every movement. I listen to the gentle clatter of the bobbins. I take in the smell of the cotton. I let my fingers trail lightly over the weave. And as my breath slows, my mind slows. And I am in another world.

About the Creator

Elaine Ruth White

Hi. I'm a writer who believes that nothing is wasted! My words have become poems, plays, short stories and novels. My favourite themes are mental health, art and scuba diving. You can follow me on www.words-like-music, Goodreads and Amazon.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.