Fear of missing out?

Young people in particular suffer from the constant fear that they might miss out on something. Behind this is the misconception that everyone else is more popular and active than they are.

What, you've never heard of "Fomo"? Then you're obviously out of the loop. If that worries you now, you may already be affected by the "Fear of Missing Out" yourself.

The dashing acronym may be relatively new, but the phenomenon itself is by no means. You can't dance at two weddings at once, the saying goes. By choosing one option, we usually have to forgo the second. But what if just the other celebration would have been the more exciting one? When friends are raving about the party of the year the next morning?

Young people in particular are often plagued by the worry that the really good events might take place somewhere else without them. About 40 percent of all teenagers say they experience this phenomenon often or occasionally, according to a survey conducted by the JWT agency in the English-speaking world. Among respondents over 50, on the other hand, the figure was just eleven percent.

AT A GLANCE

DO YOU KNOW "FOMO"?

- The wealth of information on social networks has a flip side: "Fomo" or "Fear of Missing Out" - the fear of missing out.

- Those affected, including young people, in particular, are plagued by the worry that they will miss out on important information and that the greatest events will take place without them.

- This fear is based on a paradoxical effect of social media that makes us seem less popular and less active compared to online friends.

Researchers explain this difference with the high value of social networks in younger generations. Platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter would particularly promote the fear of being left behind. On the contrary, these services are supposed to make it easier to stay in touch with other people, keep each other up to date and participate in each other's lives - even over greater distances. But the feeds of the social networks usually display an almost unmanageable abundance of pictures, status messages, and notices of upcoming events. Technical gimmicks such as "endless scrolling" contribute to the fact that new content is always popping up. This makes the wealth of information on social networks a double-edged sword. After all, our lifespan is limited; inevitably, we'll keep missing out on great events. Compared to the numerous status messages from others, our own lives quickly seem dull and dreary.

British psychologist Andrew Przybylski from the University of Essex was one of the first researchers to empirically narrow down the phenomenon. His research showed that it is mainly young men who report such worries, especially those who are not particularly satisfied with their lives. According to Przybylski, Fomo forms a kind of hinge between dissatisfaction and the use of social networks: those who cannot fulfill the need for human closeness and connection tend to worry about missing out on important things and increasingly spend their time online.

So far, however, it is not yet clear in which direction the causal chains run. Do people actually use social networks more often because they tend to Fomo? Or is it the other way around? Do social networks increase the fear of missing out? It is also possible that there is an interplay in which the two factors reinforce each other. In any case, they seem closely intertwined. The more Przybylski's subjects were plagued by Fomo, the more frequently they used Facebook and similar services immediately after getting up or shortly before going to bed - and while driving! A dangerous maneuver: typing on your smartphone while driving increases the risk of an accident by a factor of 23, according to a simulation study with truck drivers.

The smartphone as an "extended self"?

People with a pronounced fear of missing out don't necessarily use their smartphones more often than others, by the way, according to a 2016 research paper by clinical psychologist Jon Elhai. Nevertheless, their cell phones seem to cause them more problems overall. They apparently clash more often when, for example, they pay more attention to virtual contacts on their screens than to their real-life counterparts. They also complain about difficulties when they have to do without their device and are therefore unavailable for a moment.

According to an experiment by U.S. media researcher Russell Clayton, regular smartphone users become visibly nervous without their device - even if it's just for a few minutes. Clayton and his colleagues lured test subjects into the experimental lab under a pretext, ostensibly to test a new blood pressure monitor. Equipped with an electronic measuring belt, the participants were then asked to solve a complicated word search task. The trick: for half of the time, the experimenters took away the participants' smartphones, claiming that they would interfere with the sensitive measurement electronics. It was then placed one meter away on a clearly visible shelf. But while the participants were poring over their word puzzles, the test supervisors secretly called them several times. However, they were not allowed to answer the phone.

Although the entire test took only five minutes, the subjects became restless. During the short period of separation, both blood pressure and pulse rate increased noticeably, and their performance also decreased. In a subsequent questionnaire, the subjects also reported increased feelings of anxiety.

Unfortunately, the study had some methodological weaknesses. On the one hand, the number of participants was rather modest at 40, and on the other hand, the conclusion was anything but clear: It did not necessarily have to be the missing smartphone that had upset the test subjects. Even the loud ringing noises themselves could have made the participants nervous. Clayton concludes from the results of his study that the smartphone is becoming an extension of our own self - a kind of "iSelf," as he calls it. However, there is still no real conclusive evidence to support this thesis.

Even if the device is just a tool to keep us connected: It's not just smartphone advertising that works with this motif. "Don't miss a thing" is the slogan of the "Schweizer Tagesanzeiger," for example. Book titles build up pressure, such as "1000 places to see before you die" or "1000 movies you have to see" - specifications that people almost inevitably fail to meet. Health campaigns also take advantage of Fomo. An online video from Heineken shows images of a beautiful woman at a party that a young guest would likely have missed if she had crashed due to alcohol. The spot ends with the message, "The sunrise belongs to moderate drinkers."

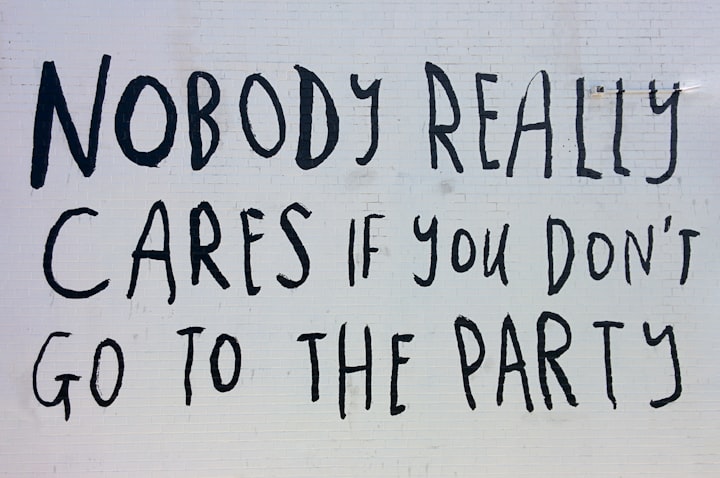

But what if the fear of missing out takes over? Can it be fought or guarded against? According to U.S. sociologist Martha Beck, who knows Fomo from personal experience, the phenomenon is largely based on self-deception. You first have to realize, Beck writes in an article for the "Huffington Post," "that the fabulous life you seem to be missing out on doesn't exist like that at all."

The so-called friendship paradox makes us seem less popular compared to our peers. After all, an average Facebook user is friends with 190 other users, but they have an average of 635 friends - more than three times as many!

In part, these perceptual distortions are due to the architecture of social networks. The so-called friendship paradox, for example, makes us seem less popular compared to our peers. An average Facebook user is friends with 190 other users, according to a 2011 estimate, but a friend of any user has an average of 635 friends - more than three times as many! At first glance, this difference doesn't seem very obvious. It becomes understandable when you consider that well-connected users have a higher chance of being friends with you simply because of their high number of friends. To put it loosely: the many friends have to come from somewhere. So if you have the feeling that your online friends are on average more popular than you are: It's in the nature of things, so to speak.

Why do your friends seem more active than you?

Analogously, Nathan O. Hodas from the University of Southern California postulated the "activity paradox". It states that one's "contacts" in social networks are usually also more active than oneself. Together with colleagues, the data scientist analyzed the activities of more than 3.4 million users of the short message platform Twitter over a period of two months. The analysis showed that about 88 percent of all users were less active on average than an average user whose channel they subscribed to. This is probably because particularly active users on Twitter usually also have more followers than others.

But it's not just the sheer number, but also the nature of the postings that sometimes makes the lives of others seem more exciting than one's own. After all, on social networks, users primarily share glamorous moments - such as vacation trips, parties, and professional successes. "Judging other people's experiences based on these selected images is like orienting yourself with the help of glasses that only show mountain peaks," says Martha Beck. She says it's easy to forget that many people's everyday lives are nowhere near as exciting as their online portrayal suggests.

About the Creator

AddictiveWritings

I’m a young creative writer and artist from Germany who has a fable for anything strange or odd.^^

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.