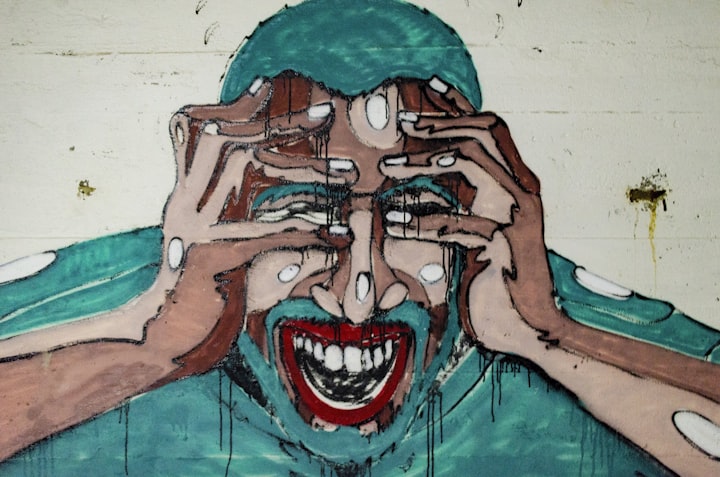

According to research, we have no idea about what we desire.

Can it be that we don’t really know ourselves

No one can tell you more about yourself than what you already know once you get to know yourself. But after all, there's a slim chance that we'll ever know everything there is to know about ourselves. Sure, we know who we believe we are, how we think we think, and other such details. However, we are far more complicated than we let on, and far more complex than we admit to ourselves. Implicit biases, heuristics, and a need for conformity are just a few examples of data that demonstrate our limited comprehension of ourselves.

We are irrational. At least sometimes.

For his contributions to behavioural economics, Richard H. Thaler was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics. He was a strong believer in the idea that humans do not always act rationally. Using psychological study findings, he contributed to a deeper understanding of people's decision-making in particular.

The concept is that we, as humans, are not all-powerful perfect computers. People, for example, are risk adverse, preferring to accept a lower payoff with the same risk while limiting their losses. This has ramifications for the financial markets. However, this concept (that humans do not always make completely logical judgments) extends well beyond economics.

Nutritional diseases, according to the author of "Nudge," are a growing problem that highlights how bad individuals are at serving their own best interests. Each person, according to Thaler, should be considered as two people: one who plans and the other who carries out (or fails to accomplish) the plan. Signing up for a yearlong gym membership may make sense to your planner side since it assumes you'll go to the gym every day or eat peanut butter smoothies for breakfast every morning. However, the doer in you might not follow through on this; it's a perfect excuse for the doer in you to keep putting off going to the gym until later in the year when it's more convenient.

Our memories aren't the most reliable sources of information about our lives.

A memory bias is a cognitive bias in psychology that influences the content of a reported recollection or boosts or hinders the recall of a memory (either the chance that the memory will be recalled at all, or the amount of time it takes to be recalled, or both). The following are some instances of biases:

Choice-supportive bias: remembering that the options you picked were better than the ones you didn't. The propensity to seek, interpret, or recall information that confirms one's ideas or preconceptions is known as confirmation bias. Conservatism, also known as regressive bias, refers to the tendency to remember high values and high likelihoods/probabilities/frequencies as being lower than they were, and low ones as being greater. According to the study, memories are not severe enough. The erroneous memory of one's former attitudes and behaviour as reflecting one's current ideas and behaviour is known as consistency bias.

The Prisoner Experience and Dr. Zimbardo: Life Imitates Life

On August 15, 1971, the experiment began with criminals being caught in their own neighbourhoods by real Palo Alto cops. During the experiment, guards (who were picked at random) were cruel to the detainees, causing Zimbardo to call the experiment off before it was due to conclude, at Christina Maslach's recommendation.

In summary, volunteers for university study were recruited through a local newspaper. The objective was to look at the consequences of power. To prevent the risk of the study being jeopardised by participant personality traits, guards and inmates were chosen at random on the day of the briefing (like in the case of some participants already being inclined to be submissive, or abusive).

The experiment started out slowly and uninterestingly, but by the second day, things were heating up. The inmates revolted and refused to follow the officers' commands. Convicts who did not participate in the "rebellion" were treated differently by the guards. One of the inmates had a mental breakdown and was spared from the experiment. As news spread that the "escaped prisoner" was returning to free the others, the guards tightened their grasp. After a few more days, the guards introduced solitary confinement, which was effectively a small, dark closet where a criminal would be forced to endure other inmates pounding on the door and shouting at them.

The purported "finding" of this study was that some unfavourable circumstances may bring out the worst in people. If the scenario has pre-defined expectations, such as a jail setting, people will simply take the roles they've seen played out in innumerable movies and television shows.

And who knows, it may be real. It is possible for good people to do horrible things.

However, it's possible that when I say "we don't truly know ourselves," I'm simultaneously implying that we trust our own judgement. For example, the decision to believe something stated in the name of science ("research suggests...") or in history books.

In his book The Lifespan of a Lie, Ben Blum, for example, brilliantly explains how the study may be based on, well, a bluff.

Random fact!! I only found out about it because I was looking into it again.

So, while the ball is still bouncing (is that how the expression goes? ), let's consider how much of "the facts" we should pay attention to.

Of sure, pay attention to everything, but don't take anything for granted. Unless there are hundreds of repeatable studies on the subject... alternatively, I don't know, I'm still trying to figure it out.

We can trust science, but science does not always imply truth. Even more so when it comes to the so-called "soft sciences," such as psychology, behavioural economics, and sociology.

That isn't to suggest that information isn't important. It is all knowledge. But, like what we assume we know about ourselves, nothing should be accepted at face value.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.