‘The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World’

Some thoughts about this Pride Month read

I don’t read a ton of biographies but once in a while, I’ll take a chance, especially if it’s somebody in the natural history field. And, thus, for Pride Month, I have embarked on, “The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World” by Andrea Wulf. The outgoing Prussian explorer sounded like an interesting guy who did a lot of interesting things — and, from the start, his adventures exceeded all my expectations.

Dude’s amazing.

But the way his life is described, well… I’ve got questions. And so I’ve decided to record my impressions.

[Note: Since I’m listening to the audiobook, my progress is told in percentages, not page numbers. Also, you will find a complete list of photo credits included at the end.]

June 2 (18% percent)

Wow. Cool guy, this Alexander von Humboldt. I had no idea the character of Faust was inspired by this guy’s actual personality or that he was so much of a muse to the middle-aged Goethe.

I guess I only knew the part about him being the gay explorer hiking relentlessly around South America.

But there’s something really weird about this book. It appears to be written in subtext — at least what I’ve heard so far.

I looked it up, and, “The Invention of Nature,” was released in 2015, so I’m not sure it was necessary to be quite so roundabout.

Because, honestly, it’s getting a tad annoying. How many ways can one author find to let us know Alexander’s gay without once saying, “Honey, he’s gay?” And why do so many of those ways of telling us have to invoke stereotypes from, I dunno, the 1970s?

Cold mother. Feminine hands. Lonely and isolated. Seriously self-harming.

(Note for people who appreciate trigger warnings: I wish I’d skipped the last three minutes of the first chapter when we are told in what I regard as unnecessarily squirm-inducing detail just what he did to himself with his scalpels, electrodes, and various chemicals. It’s about 6% in. When the narrator starts talking about the 4,000 experiments, you may want to take that as a hint to move on to the next chapter.)

Eventually, our hero grows out of this stuff, the cold mother dies and leaves him a pile of money, and he acquires an endlessly patient sidekick, the French botanist Aimé Bonpland. Together, after a suitably daunting series of obstacles, they are free to set sail to “discover” South America.

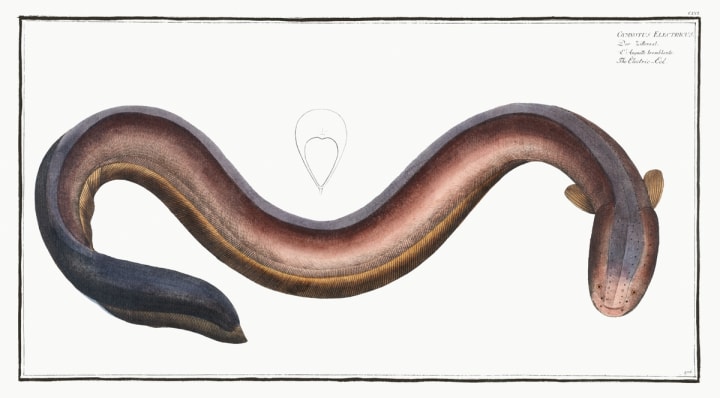

I’m liking the cheerful French sidekick a lot. Nothing much flusters this guy, not even that time when Alexander nearly got them both killed in a lake full of electric eels.

Now that’s love, I think.

Aimé isn’t Alexander’s first love, and he’s probably not the most passionate by a long shot, but he’s just somehow so huggable.

But, also, unless my attention really slipped somewhere, the word “gay” has never yet been mentioned.

Here’s a guy happy to leave Paris to sail across the world to climb ridiculously high mountains in inappropriate footwear, get eaten alive by mosquito hordes of Old Testament density, and, oh yeah, let’s not forget the part about getting zapped by the electric eel roundup.

C’mon. Doesn’t devotion like that deserve to be named?

Maybe this choice was made to maximize the chances of the book landing in libraries, and I shouldn’t be too grumpy. After all, gay books are being hit particularly hard by censors in school libraries, at least in the United States, which is (I’ll assume) a large market for this kind of book.

Regardless, I’ve got a guessing game going. How far do I get in this book before I hear the word, “gay?”

June 3 (23%)

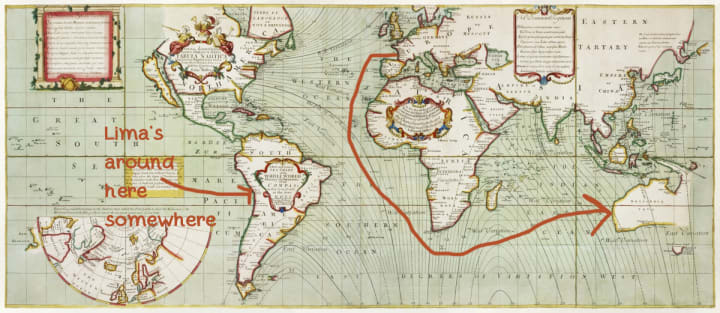

At the beginning of Chapter Six, Across the Andes, our energetic pair is on their way to Mexico via Cuba, but Alexander reads a newspaper article in Cuba about an expedition to Australia. Somehow, he decides that the best way to join this expedition is to travel overland across the Andes to Lima, Peru.

As far as this reader can tell, there was no evidence this expedition was heading for Lima or that it had the slightest interest in picking up Alexander and Aimé even if it was, but why let the little nagging voice of negativity squash a perfect plan?

Cheerfully acknowledging that they would probably die, they arrange to ship their specimens to Europe. And away they go. Mission creep happens, and also it becomes obvious nobody’s sailing from France to Australia via Peru, but never you mind, because now Alexander decides they will climb “all the volcanoes he wanted to investigate.”

Apparently, Quito is a nice central location for “all” the volcanoes, and soon the dashing Alexander was annoying the unmarried beauties of the city by blatantly ignoring them. One of them who left behind a grumbling letter was the sister of the 22-year-old man who became Alexander’s new “infatuation.”

The placid Aimé, it seems, had grown “cold” even before they departed Spain — or so says one of Alexander’s letters home — “that means I only have a scientific relationship with him.” Maybe so or maybe they were just having a low moment, but have we finally reached the point in the book where the author says, “gay?”

Spoiler alert: We have not.

But at last the author has recognized that she must say something. After all, the lovely younger man is destined to remain by Alexander’s side for the next few years.

(The imperturbable Aimé doesn’t object. Did we really think he would?)

While this reader is hoping for a throuple but suspects a serial monogamy thing where Alexander’s most passionate love has been transferred to this new man, the author feels called upon to say:

“Humboldt never explicitly explained the nature of these male friendships, but it’s likely that they remained platonic.”

Girl, please. Nothing strikes me as less likely.

Especially since a minute or two later, she lets it slip that Alexander and the new man are sharing a bed.

At this point, I’m getting a strong whiff of gay erasure, and I have to turn off the audiobook for the night.

June 4 (41%)

After five years of adventure and plant collecting, Alexander declares it is time to return to civilization. Never the bashful sort, he invites himself to visit Thomas Jefferson, the President of the United States. We are assured that Jefferson, a lover of plants and gardens, will be thrilled.

You bet he’s thrilled. It’s the notebooks he’s after. Jefferson deftly extracts all sorts of maps and other strategic information about the Spanish-controlled territories while pretending to be a simple farmer who sort of backed into running a large country.

Then Alexander’s back to Europe to hobnob with more of the rich, the beautiful, and the titled, at least until the money runs out.

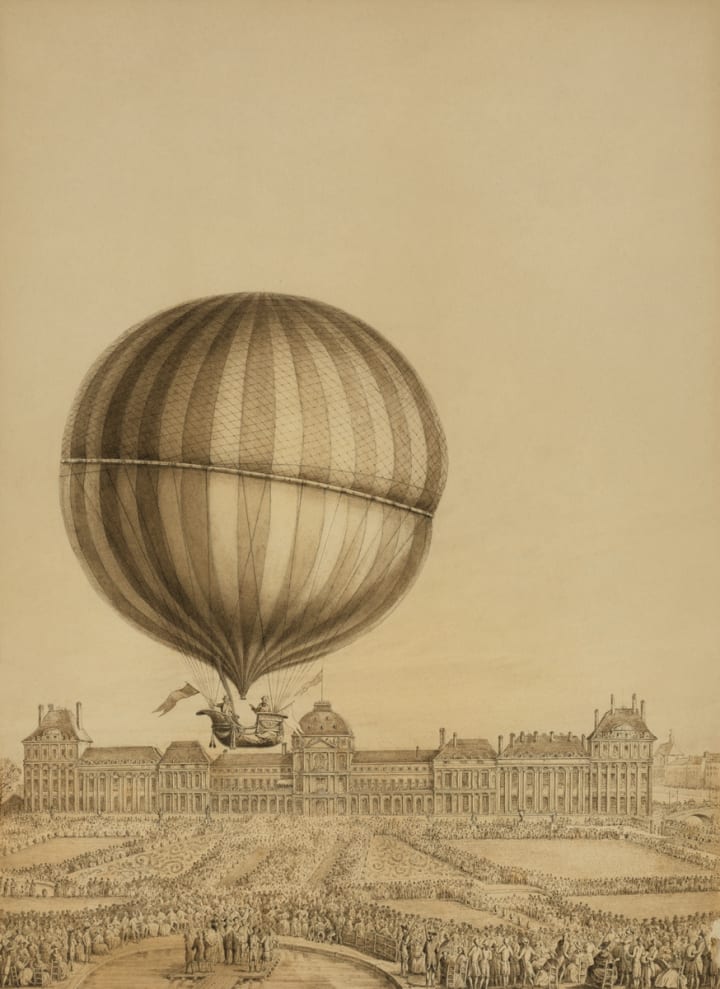

The gorgeous young man from Quito relocates to Madrid. Alexander replaces him with dashing young balloonist/chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac.

Since “Gay” is part of his name, it doesn’t count in the game of, “How far will we go in this book before the author says gay?”

Alexander writes a lot but in those days, writing doesn’t seem to pay, it costs. The engravers for all those illustrations don’t come cheap, you know.

Fortunately, the king of Prussia provides him with a salary and the title of royal chamberlain, in return for which Alexander does the minimum.

You think you’re good at goofing off at your job?

At one point, our hero effs off to Paris for a good 15 years. He persuades the king to keep paying him because, well, he needs to be in Paris to do book research. I thought he’d done the research in South America, but the king swallows the story and keeps the money coming.

This one caper alone should qualify Alexander von Humboldt as a true hero to any writer.

Francois Arago, a young scientist who comes complete with a daring prison escape backstory, “quickly became Humboldt’s closest friend. Perhaps not coincidentally, at the exact moment when Gay-Lussac married.”

Nope. No throuples in this story. Our hero is a serial monogamist through and through. The relationship with Francois is described as “tempestuous,” but it’s also long-lasting.

Again, we’re asked to read between the lines, but the experienced subtext reader will get the general idea.

All in all, it seems that Alexander does the bare minimum required by his society to pretend to be in the closet. Rich guy privilege, I suppose. Also, cute guy privilege, as we’re assured he looked a decade younger than he really was even as he approached forty.

Everybody loves him but Napoleon, who is persuaded he must put up with our hero since he is an “ornament” to France. Probably doesn’t hurt that Josephine adores Aimé, who still retains strong ties of friendship with Alexander despite Alexander’s kvetching that Aimé writes too slowly.

You can’t really blame Aimé for this. He now has a real job as conservator of the first Empress of France’s famous garden, and this reader gathers that Josephine expects him to show up for it.

June 5 (50%)

Jefferson isn’t the only one making use of Alexander’s maps. Hiking buddy and salon pal Simón Bolívar cultivates the friendship too. One wonders how much our hero knows he’s being triangulated. Jefferson, now out of the Oval Office — was it oval then? — is mining him for data, and so, course, is Bolívar.

Our hero has become a hopelessly addicted writer, and when he’s not writing books, he’s writing letters, so he’s pretty easy to mine.

Spain must really, really regret giving Alexander that travel pass, because he openly comes out against colonialism and its impact on both the people and the environment. Skeptical at first, he becomes an enthusiastic supporter of Bolívar’s plan for liberating South America.

The British take note. When our hero travels to London to wrangle a passport to the Himalayas, the East India Company says ix-nay even though his older brother Wilhelm the diplomat is stationed in London.

To add insult to injury, the brother makes Alexander and the boyfriend (still Francois Arago) stay in a hotel since he doesn’t approve of the relationship. Poor Alexander is 48. You might think Wilhelm would have accepted reality by now.

The poets love Alexander though, and so in London he lingers a little longer.

June 6 (62%)

The fifties hit hard. Aimé didn’t expect to spend so many years writing books. When the old mid-life crisis strikes, he arranges to return to South America with or without Alexander. It’s without, but Alexander tries to send money.

Too late. Poor Aimé never receives this gift, for he has already been dragged off to Paraguay in chains. His knowledge of deep agriculture is too dangerous to the monopolists.

Meanwhile, the king of Prussia has had enough. If Alexander wants to keep getting paid, he needs to get his butt back to Berlin.

The writing continues apace, and so does the mentoring and influencing of rising scientists, but the serious work must now fit around the king’s demand to be entertained by tales of foreign adventure. Le sigh.

But, at long last, a new expedition is arranged — to Russia, of all places. Politics are somehow involved. Also Alexander’s ancient credentials as a mining engineer.

At the beginning of Chapter 16, Russia, we realize that 59-year-old Alexander is now traveling with Johann Seifert, the last love of his life, but we only really know this if we cheated and looked up some gay history online. Our author tactfully describes Seifert as the entourage’s “huntsman” and collector of specimens — and, oh yeah, Alexander’s future house ̶h̶u̶s̶b̶a̶n̶d̶ keeper.

This is 58% of the book. At this rate, we could well reach 99% before the author says, “gay.”

Anyhoo, expecting treasure to be found, Czar Nicholas I agrees to pay for the expedition, but Alexander must swear to abstain from social commentary like grumblings about the treatment of serfs, and, of course, he must stick to his arranged itinerary.

Ha.

Drawing on his early years as a mining engineer, Alexander discovers actual, literal diamonds in the Urals — no, I can’t make this stuff up — but it’s a good thing too because next he goes all the way to China, talks to Siberian prisoners, and otherwise treats the absolute czar’s orders as polite suggestions.

But, in the end, all’s well that ends well, and this is it, the last great voyage of his life.

It seems there were only two — Latin America and Siberia. About six years or so of travel all told.

All the rest was the gathering, analyzing, and sharing of the learning.

Funny what a small percentage of life the actual living is — and what a large percentage is the writing and talking about it!

June 7 (83%)

Much writing of books. Much writing of letters. Much meetings with younger scientists and creatives in search of inspiration and patronage, for Alexander’s kindness to the up-and-coming has become a global legend.

Even when freed from durance vile, Aimé will never return to Europe, but the two old adventurers exchange affectionate letters until the end. One exchange mourns the passing of Francois Arago.

Aimé goes, and then Alexander goes.

89 years old.

Johann Seifert, who has lived with him for 30 years, inherits everything (Note: Seifert is married, and his wife and kids live in the house too, along with Alexander’s chameleon and parrot. You may interpret that as you like, but it seems that everyone is happy and taken care of, and that’s what’s really important, isn’t it?)

Anyway, as a beloved citizen of the world, Alexander von Humboldt’s death is one of those celebrity deaths that leave all the world weeping.

Pointless to summarize all the people, sciences, and arts he influenced. This little review is already too long. Besides, one should read the book.

Although, and I remain annoyed by this, the author has still never once said, “gay.”

June 8 (100%)

And she never will. The rest of the book is about the passing of the baton, with a selection of biographies of the next generation of men who explicitly credit Alexander von Humboldt with being their inspiration.

All in all. Fascinating guy. He did a lot. Lived a long time. Did good work. Inspired and supported a lot of other people’s good work.

But I’m not sure if it’s a Pride Month read if the writer never says gay, so I'm currently considering my next read. I'm open to suggestions.

Note: This article was previously published on Medium, but I have republished it here for the convenience of my natural history fans on Vocal Media.

Photo Notes

*Featured Image is a painting called, Alexander von Humboldt und Aimé Bonpland in der Urwaldhütte By Eduard Ender (1822–1883) — Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

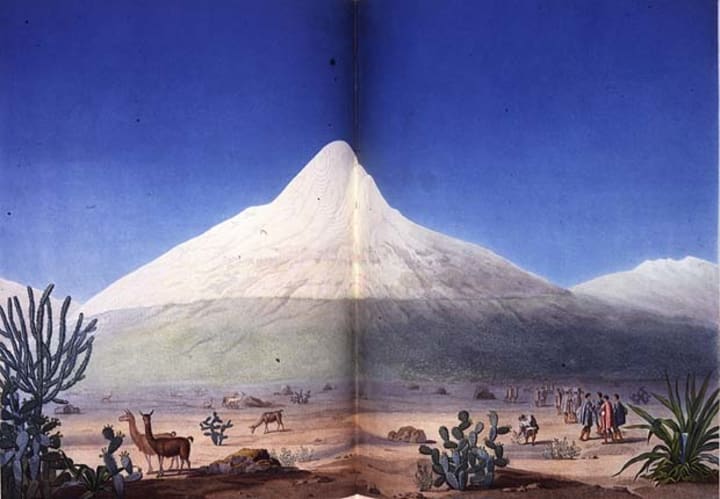

*The watercolor of the Chimborazo volcano was based on the notes of Alexander von Humboldt. It was f irst published in Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland’s work Voyage de Humboldt et Bonpland…Ière partie; relation historique…, Paris, F. Schoell, 1810/ Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

*Electric-Eel (Gymnotus Electricus) from Ichtylogie, ou Histoire naturelle: génerale et particuliére des poissons (1785–1797) by Marcus Elieser Bloch. Original from New York Public Library. Digitally enhanced by Rawpixel. Public domain.

*Public domain vintage world map via Rawpixel with my scribble on it to show you even an American knows more geography than to think you sail to Peru to get from France to Australia.

*Balloon flight over Paris thanks to the Library of Congress via Rawpixel under Public Domain license.

*Captive Humboldt’s Penguins photographed by Eskisehir Hayvanat Bahçesi via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

*Rain of coins image by poolpiik via Deposit Photo.

*Mountains, Nepal by the author Amethyst Qu.

*Diamond Photo by Bas van den Eijkhof on Unsplash.

*“Sure, Jan” Green Heron /photo by the author Amethyst Qu.

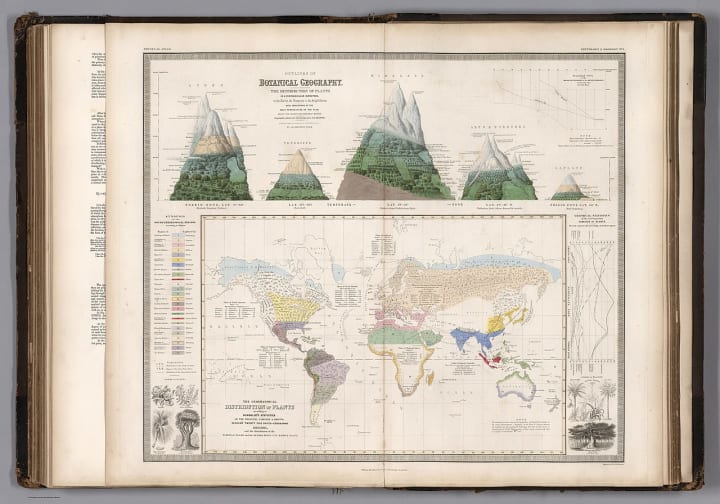

*From A. v. Humboldt’s Geographical Distribution of Plants (1850) via Wikimedia Commons under Public Domain License.

Interested in South American natural history?

Two more stories you might like:

About the Creator

Amethyst Qu

Seeker, traveler, birder, crystal collector, photographer. I sometimes visit the mysterious side of life. Author of "The Moldavite Message" and "Crystal Magick, Meditation, and Manifestation."

https://linktr.ee/amethystqu

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.