How Cannabis Inspired Jazz Musicians

While cannabis inspired jazz musicians throughout the 20s and 30s, few of them were prepared to make a stand in defense of legalization.

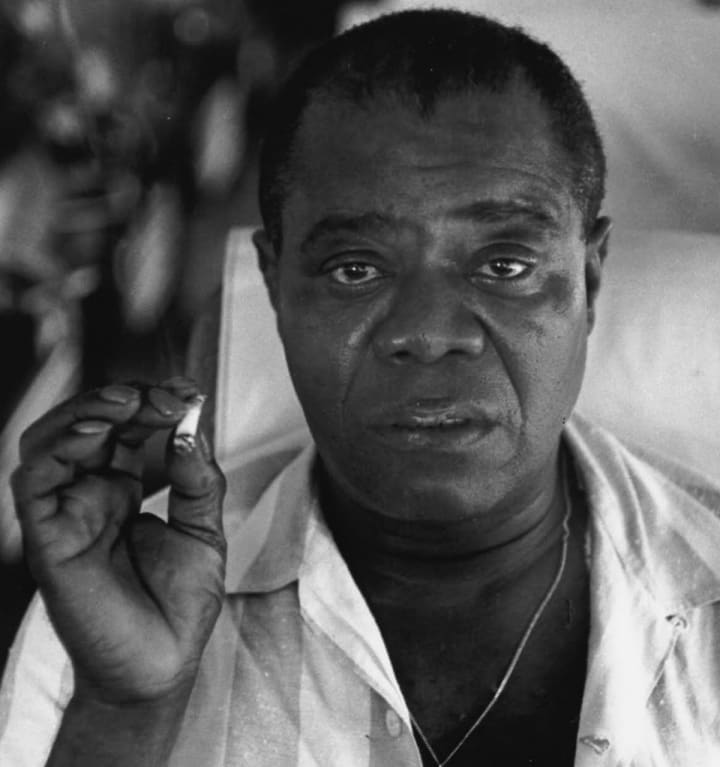

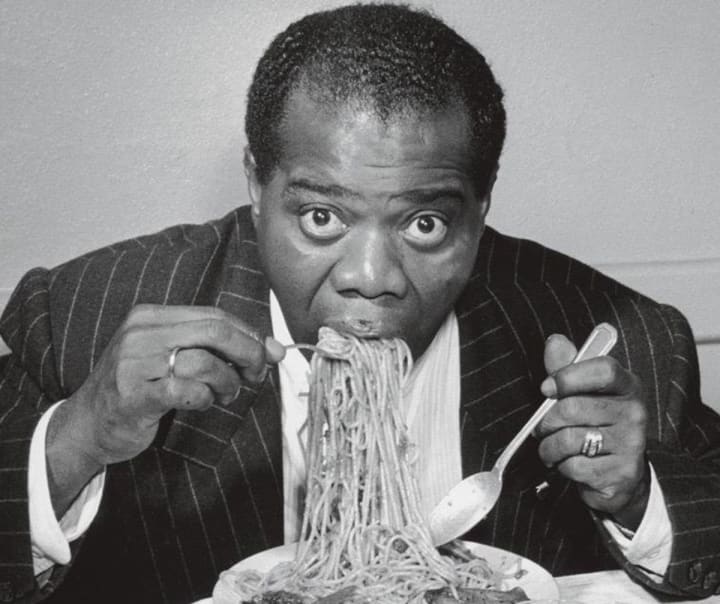

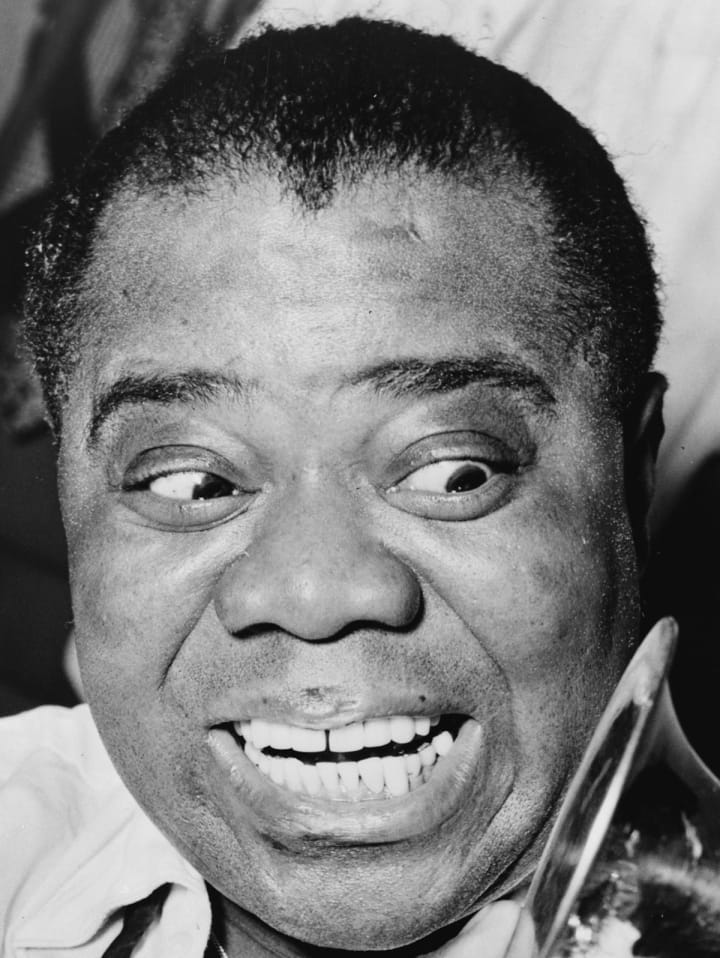

Louis Armstrong was a much more courageous man than the young firebrands of a later generation gave him credit for. As for "putting it down," there a certain doubt creeps in. I suspect that until the end of his life, when everything was "cool," Louis didn't refuse a joint, but as he says he was "way up there in age" and not prepared to make an open stand, attend smoke-ins, or light up on the stand. He didn't however deny "the beauty and warmth" of how cannabis inspired jazz musicians. He never denounced "Mary Warner."

Dope and Black Jazz

From the earliest days dope was Black Jazz's secret, but things were always difficult for Black Jazz musicians. There were so many pressures and the use of dope was yet another weapon that could be used to harass the jazz man. Louis' one bust for instance was, according to the policeman who arrested him, because a bandleader up the road, probably a user himself, got jealous at Armstrong's greater success and "dropped a nickel" on him. For jazzmen, of necessity, dope was a hilarious secret.

Around it arose an elaborate slang. Most people know, and now laugh at as old-fashioned, the word "reefer" meaning a joint, but less familiar are the disused words for the weed itself: "muggles," "Mary Jane" (or Warner), "gage," and "shuzzit." A regular user was known as a "viper," and the object of smoking was to get either "high" (still in use) or "tall" (archaic).

As dope was mostly confined to Blacks or those white jazz musicians who admired or hung out with Black jazzmen after hours, it was ignored as a general problem, and throughout the 20s and 30s it was possible for jazz and swing musicians to put out a large number of celebratory records knowing that either they would be largely ignored by the white record buying public or that the argot would conceal the meaning. Comparatively recently Stash Records issued an L.P. called Reefer Songs, 16 cheerful tracks describing the pleasures of dope, all of them issued between 1932 and 1944.

Cannabis in Music

On Bessie Smith's "Gimme a Pigfoot and a Bottle of Beer," the Empress of the Blues herself demands "a reefer and a gallon of gin," a mixing of intoxicants that would appall the more puritanical devotees of Home Grown perhaps, but for such a full-blooded hedonist as Bessie would seem no conflict. Amusingly enough Bessie's niece, Ruby, while being questioned by Chris Albertson for his fine biography, became impressively indignant when Albertson asked if her aunt indulged in dope or shit. "No, Bessie never touched nothin' like that—just regular reefers." A classic example of linguistic confusion.

It would seem logical that, following the revival of interest in early jazz in Britain towards the end of the 40s, that those of us involved would have taken up dope as well, but in fact this didn't happen for a number of reasons which I shall try to explain here.

This revival coincided with the Bebop explosion; a rival school for whom, with very few exceptions, the music began with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. This initial antagonism, later much resolved, was so extreme that it went far beyond the music itself and dictated two entirely separate life styles. Revivalists were studiously scruffy so Modernists were sharp. Modernists were cool, so Revivalists were extroverts. Modernists were known to smoke dope, so Revivalists confined themselves to alcoholic excess.

But why, as the heroes of the Revivalists had also smoked, did this taboo remain? Well for one thing it was not generally known. The records on the subject, with the exception of Bessie's one reference, were unobtainable, and none of the earlier jazzmen had come out front to discuss how cannabis inspired jazz musicians. Then, whereas the Bebop musicians were mostly professionals who had crossed the Atlantic playing on the boats, met their idols, and observed and copied their habits, the Revivalists were largely semipros and, due to the embargo on American jazzmen coming over, hadn't even heard a jazz giant in the flesh, let alone spoken to one. Finally, it was Bebop which attracted the still sparse West Indian immigrant population with their tradition of Smoking and in consequence access to the weed. During the 50s a few British Modernists were busted and given fairly Draconian sentences. This strengthened the Revivalists reluctance to try it. What you've never had you don't miss.

Growing Tolerance

Towards the end of the decade, with the gradual breakdown of hostility between the two schools, we'd become more tolerant. We'd smelt it, and seen it smoked, but few of us had crossed the barrier. It was associated with flattened fifths, sharp suits, and turning your back on the audience. Then came the 60s, rock burst in, jazz, whether Bebop or Traditional, was swept out of the way, and dope became not a minority pleasure but a crusade and a cause.

For a jazzman, the 60s were professionally a disaster, but for someone interested in general in social development they were a fascinating if at times infuriating decade. The principal development was the sudden elevation of youth into a religion. Youth itself was not just a stage between childhood and adulthood, but the only virtue, and dope was one of the ways it cut itself off from anyone over thirty. Dope was no longer the modern jazz world's secret, or the American and West Indian Black world's relaxation. It was a provocation, a sign of belonging, a means to distinguish "them" from "us."

I must admit I found the free-masonry of dope as irritating as I was intended to. (I was around thirty-eight in 1964.) Those beatific smiles which were so exclusive, those endless discussions as to quality and source, that deliberate rejection of language as a form of communication. On the other hand I tried it and found it pleasantly relaxing, dream-inducing, the reverse of aggressive. I preferred and still prefer alcohol, but could see little harm in it, certainly no more harm, and probably less, than in whisky. The law, however, thought otherwise, using its illegality as a stick to beat the young. Thus long hair equalled dope, and the police took to stopping long-haired boys in the street to search them and were frequently rewarded. The point was that long hair, like dope was a cause, a fairly negative one in my view, but not to long-haired dope smokers. Caution was frowned on.

As a result dope could be planted and no magistrate would believe that any long-haired hippy wasn't guilty. Dope could be used, and was, to harass anyone with unpopular views; the Oz defendants for example. I had no hesitation in signing the advert in The Times. While whisky and cigarettes are advertised everywhere, it seemed to me insane to single out marijuana as a criminal substance, and nor did the escalation theory seem in anyway convincing. Of course most heroin addicts probably started on dope. So most alcoholics, dying from cirrhosis, started with a glass of beer. On the other hand it seemed to me by making marijuana illegal you linked it with other illegal and undoubtedly dangerous drugs, equating the young man with more than he needed for his own use and selling some to a friend, with the dealer, usually far more cautious, who made his living pushing addiction and despair. My wife's work for Release revealed to me what I might otherwise have never believed without witnessing it; the lengths the law would go to bust those whose lifestyle, as a whole, they disapproved of. The extraordinary witch hunt against the Beatles and the Stone were of course widely publicized and raised doubts and misgivings even in the August columns of The Times, but no such publicity was afforded the thousands of kids on the street or in squat who were equally at threat.

Cultural Hypocrisy

Nor, by that curious double-think which comes into play the moment money is involved, was anything done to suppress all those overt references to dope in Rock music. "Smoke dope," sung the superstars. "Turn on! Drop out!" And the kids did, and got busted.

However, during the 70s much of the steam went out of the issue. Dope, while still much smoked by all classes and age-groups, is no longer a cause celebre, nor even especially fashionable. Playing as we do at universities we notice, it may be partially economic of course, that whereas five years ago you could get a contact high simply by breathing in and out, there is much more drinking and far less smoking. The press no longer raise their hands in horror. There are other, more serious problems around, and the age-group split has in part healed.

Yet this doesn't mean there are no more arrests, doesn't rule out the possession of however small a quantity of hash or grass as a way to pin down those considered to be trouble-makers or antisocial. In a way the general public tolerance is a danger. "Nobody cares anymore do they?" is the general attitude, but that's just because the news value has gone out of it. Its still as unfair as it ever was—perhaps more so. The young doctor or schoolmaster who enjoys a joint to relax at home in the evening will probably suffer no consequences. The working-class kid on the streets is statistically likely to be less secure. All strength to the campaign to legalize the use of this comparatively harmless narcotic not, in my view, because of its positive or beneficial qualities if such they be, but because its illegality is partial, unjust, and hypocritical.

About the Creator

Frank White

New Yorker in his forties. His counsel is sought by many, offered to few. Traveled the world in search of answers, but found more questions.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.