History of the Marijuana Lab Mouse

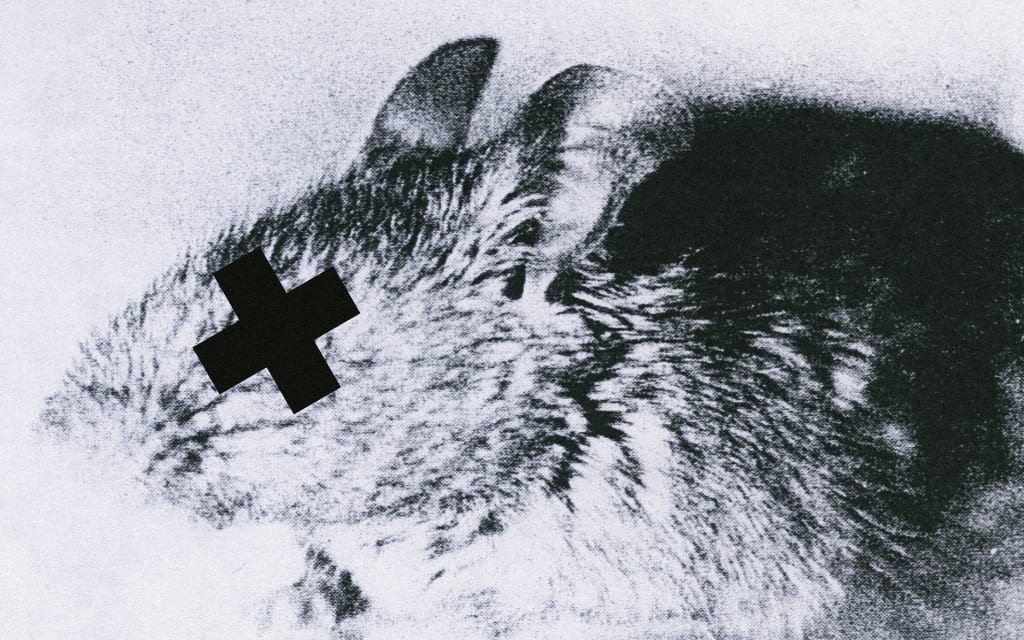

Marty, the legendary marijuana loving mouse, has died.

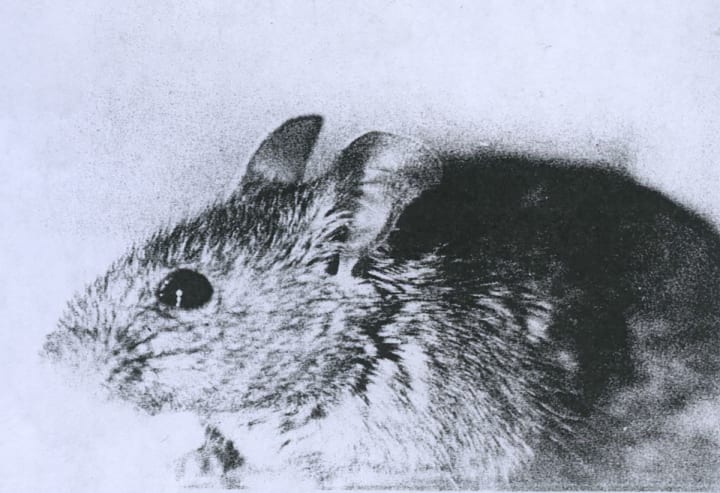

Nobody says you have to sit Shiva, but it's sad when the mouse you got high eventually dies. The laboratory mouse is like a small friend. Mammal of the Rodentia classification, bred specifically for scientific research. Usually of the species Mus musculus, these mice really keep to themselves, extremely well- behaved. Mice belong to the Euarchontoglires clade, and so do human beings. This is always shocking to many people who never bothered to ask why exactly we test on mice before performing similar testings on people. Some amongst us actually believe this is because nobody gives a shit about what happens to mice, because we can just clone another 1,000 when we need them. But of course there is actually a scientific reason. The close relationship, or more appropriately the associated high-homology with us humans, their ease of handling and maintenance, and their actual birthrate made mice effectively the best test subjects for human-oriented research. The classic laboratory mouse genome has been properly sequenced and an abundance of mice genes have human homologues. Some say God works in mysterious ways, some say evolution is so absolutely fascinating. When it came to Marty, it didn’t matter. He was my friend. But that was along time ago, in a different America.

Heroes Get Remembered, But Legends Never Die

To those of us who knew the marijuana-munching rodent, his death brings as much relief as anguish. Meteoric as was his rise, his day in the sun proved in the end to be a mixed blessing. Fame brings trials to the strongest of wills, and when you're:

- A mouse in a man's world and

- A pioneer in an emotion-laden cause, the spotlight can scorch your fur.

To Marty's credit, he maintained his integrity to the end, but his final weeks, spent incarcerated in the San Jose, California, police department, were weeks of increasing withdrawal punctuated by violent outbursts, the signs of a defeated spirit.

No one knows just what genetic or environmental conditions set the philosopher-mouse on his great crusade. We have only these facts: One day late in 1974, the San Jose narcotics squad detected a number of holes in its evidence bags. A small amount of marijuana was missing; a much greater amount was scattered around, Case 96-1454 hopelessly mixed with Case 96-1455 and so on. If the defendants ever found out, a lot of convictions would go down the tubes.

The next day, more evidence was destroyed. And the burglar was no bungler. "We're on the third floor and the lights are never off," said one mystified police officer. "The only way into the evidence room is up staircases and through closed doors and an elevator." And yet the criminal activity continued, always with the same pilfer-and-scatter MO. The holes grew bigger. Bags were shredded. Whole cardboard box bottoms fell out.

One day Marty was rummaging through some #7 Maui Wowie when the box opened. He looked up and saw a giantess. The courage and quickness, the crisis instincts both friends and adversaries came to admire, took over. "Nothing is true. Everything is permitted," flashing through his mind, he leaped onto the giantess arm, and from there to her shoulder. She screamed and ran from the room. Marty landed on a desktop, leaped three feet to the floor, and scurried away. "He was very fast, and he could run under a door without slowing down," recalls Sgt. Hal Lail.

For two months the police tried in vain to trap Marty. "We even put a female mouse in a trap, hoping to lure him in," says Lail. "She turned out to be a fag." Finally they baited a trap with marijuana seeds, and the master criminal was caught the first night.

The wheels of justice ground to a halt as Marty was quickly railroaded through trial and sentenced to life imprisonment as the narcotics division mascot.

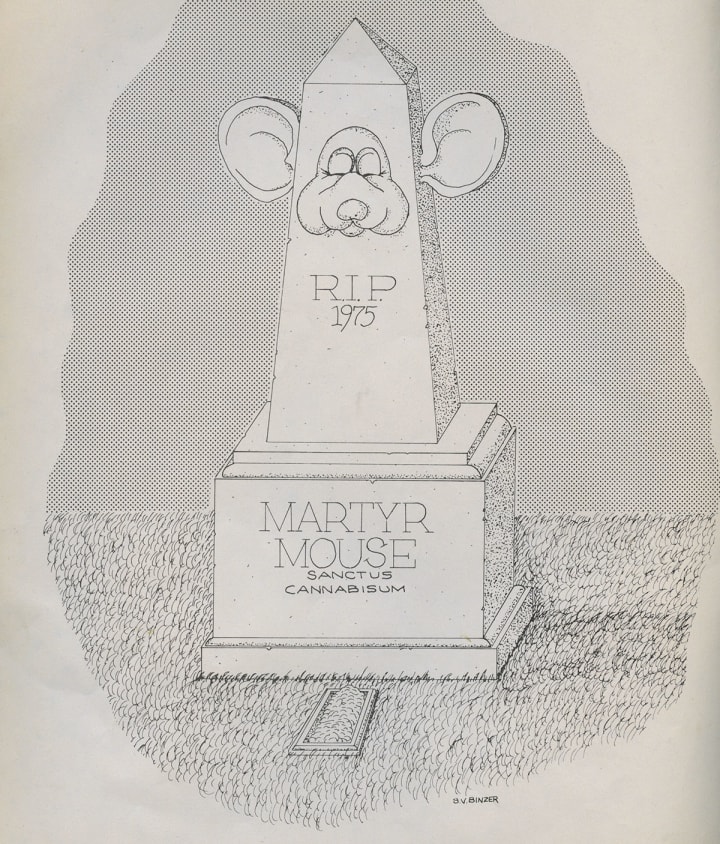

Illustration by S.V. Binzer

Rise to Prominence

The press got wind of Marty's exploits and he quickly became a national figure. He was not yet a hero to the dope culture, only a strange bedfellow. His motives could only be speculated. "We know he had no family here in San Jose," says Sgt. Lail, noting that with his capture, the raids on the stash room stopped. Thoughtful heads, reflecting on Marty's eating habits, wondered whether Uncle Sam's wanton destruction of marijuana fields affected mice even more than men.

Marty did not remain in prison long. Dr. Ronald Siegel, a psychological researcher at UCLA's Neuropsychiatric Institute (NPI), had been investigating animal intoxication for several years. He had published his results in The International Journals of the Addictions and The Rip Off Review of Western Culture, concluding that, yes, animals do get high, but from different drugs than those preferred by humans. He wanted Marty for experiments.

The police agreed. No one asked poor Marty.

Quest for Freedom

From the beginning, Marty's relationship with Siegel was strained. Feeling, as he did, that cops are the ultimate repository of our bad vibes, he was undoubtedly happy to leave his captors. He saw his future as unpredictable as his past. But still somewhere he hoped his transfer would open the door to escape. This became a source of extreme frustration.

He made his first bid for freedom in the men's room of the San Jose airport. Siegel, having sought unsuccessfully to waive airline regulations prohibiting Marty from riding in the passenger section, tried to remove him from his cage and hide him in a styrofoam cup.

As Siegel opened the cage, Marty sprang out and darted across the floor. Siegel dropped to all fours and raced after him. Too late, Marty realized he had run the wrong way; he was trapped in a corner. Siegel recaptured him, but not until Marty bit him on the hand and a toilet bumped him on the head. A man who entered the room while he was on the floor gave Siegel a humiliating stare.

At UCLA, Siegel treated Marty well. He conducted food preference tests, keeping Marty well-stocked with U.S.-grown Mississippi Botanical of up to 4.0 percent tetrahydrocannabinol. It was quite a treat after all the commercial mouse and hamster food in San Jose.

Still, Marty remained flighty. He made four separate escape bids, each time notching Siegel's finger with a new scar.

Ironically, his imprisonment aided his crusade. From the day he arrived at UCLA, he received constant media coverage. The beleagured Siegel even held a TV press conference at NPl, hoping that a one-time shot would end the hubbub.

But the press only grew hungrier. That's when I first met the rodent celebrity; Siegel asked me to act as his press secretary so he could continue his work.

My first meeting with Marty did not go well. He buried himself beneath a pile of wood chips and refused to socialize. Siegel told me he'd found no behavioral differences in Marty on or off the weed.

I later perceived in this remark the crux of Marty's differences with Siegel. The doctor's scientifically trained mind looked for only the measurable clues to Marty's mental state. His appetite remained healthy, and his continued escape attempts belied any possibility of amotivational syndrome.

But beneath those marks of a courageous fighting spirit, telltale signs of paranoia and withdrawal were setting in. Marty spent long periods under the chips, finally coming to regard every university degree as a degree in police science. He had become a martyr mouse. In a conciliatory gesture, Siegel trapped five female mice in a garage in nearby Inglewood and introduced one, a furry brunette named Mary Wanna, to his reluctant subject.

Like a teenager meeting a girl for the first time, Marty's first reaction was to run behind a food bin in a dark corner of the cage. After a while, he came out and nervously ran on his wheel. "Then Mary Wanna began running with him," recalls Dr. Siegel. "They were really cute in those days."

While some may try to explain Marty's celibate relationship with Mary Wanna as a result of marijuana-induced lowered testosterone level, those of us who knew him were aware of his fear that Siegel had fixed him up with Mary Wanna solely to breed progeny for experimental purposes. He knew he was no ordinary mouse. Siegel was not to be trusted, and how could Marty be sure Mary Wanna was not in collaboration with him?

Free the Rodent!

That very month, January, 1975, the Free Marty movement formed at UCLA. Their misinterpretation of his sublime mission and their talk of violent and illegal acts to free him only upset Marty more. Except for the dope issue, he was nonpolitical, having given up left and right when he gave up shoes. With regard to dope, he gave the world Marxist-Grouchoism #1. (Thesis: When the social order becomes physically oppressive, more people take to dreaming. Antithesis: An imbalance occurs between dreaming and doing. Synthesis: The social order falls.) At night he would huddle trembling in Mary Wanna's cage (Siegel had switched the two in an attempt to foil any mouse-napping break-in attempts) and brood on how his mission had gone awry. He had sought apparently to save the marijuana and now some Mickey Mouse club – co-founded by someone named, appropriately enough, Lois Lane – was portraying him as "a little guy who dared to challenge the system." A local entrepreneur began selling Free Marty bumper-stickers and tee shirts.

Siegel issued a statement describing the club and the tee shirts as natural steps in the creation of an American folk hero. "The study of Marty's developing image will tell us much about the changing mores and behaviors of our society," he said. For Marty, the tee shirts were the last straw, and Siegel's remarks only showed his insensitivity to Marty's plight. He burrowed under his chips and refused to come out, even when several hundred “Free Mouseketeers” marched on NPI and demanded his release, bringing men in white coats to the windows.

The march capped a rally at which attorney Kenneth Dusick presented UCLA Dean of Students Robert Ringler with a writ demanding Marty's release. He was a victim of police entrapment and had been denied a jury of his peers, Dusick charged. "He was tried by a kangaroo court and wasn't even provided an interpreter."

An Unfortunate Decline

Siegel finished his experiments in May and in July an officer escorted Marty back to his San Jose prison. Despite Marty's conviction that you can miss old age by running into it, his final months were marked by increased misery and further mental deterioration — whether induced by his circumstances or by terminal cannabis brain damage is a matter of whom you talk to. He found one ally among his captors — Sgt. Aubrey Parrot, who built him a cage out of a baking pan and quarter-inch screen, furnished it with a treadmill and two styrofoam coffee cups taped together, cut with two holes, inside which he could escape the interminable glare from the 24-hour lights.

But he was a mouse with a mission, in the hands of the opposition. He understood how Dr. Leary felt. "He was skittish and shy and wanted nothing to do with you," said Lail. "He drew blood several times. He couldn't be handled without leather gloves." He chewed up his styrofoam cups, inexplicably eating himself out of his house and home. His philosophy became less coherent — he believed he was in contact with extraterrestrials and insisted he could leave his cage through astral projection.

Similar to my father, Marty's once-brown fur had long ago greyed around the ears. In October, he developed a skin condition, from which he was not to recover. A San Jose veterinarian, who wishes to remain anonymous, heard of Marty's plight and volunteered to treat him. By the time he was transferred he had a massive infection on his side. Cortisone treatments were needed, but by then his temperament had so worsened that "it had to be administered orally, since you couldn't touch him."

Marty's final enlightenment came in the vet's office on Tuesday, November 4th. By mouse standards he was an octogenarian, and the police attributed his death to natural causes.

Funeral arrangements were modest, but at least he was spared the ignominity of his captors' proposed end. "We were planning a burial at sea," says Sgt. Laii. "We were going to flush him down the toilet."

"Marty's death should in no way be considered a marijuana-related fatality," said Siegel at his passing. "Marty is not dead. He has simply left his body and gone on to the next level."

The Legend Lives On

Compared to his life, Marty's death was peaceful. And despite the disappointment and personal tragedy that shrouded his mind and occluded his spirit, his legacy is great.

It is still too soon to assess the scope of Marty's contribution to the historic social movement to which he was dedicated. The police, abashed at their role in contributing to his martyrdom, are unwilling to comment on it. Sgt. Jim LeRoy, who handled most of Marty's publicity in San Jose, had "gone home for the day," and when we called Sgt. Lail, he was evasive: "Drugs cause people to be criminals. I don't know about mice."

But whatever drove Marty to his mission, and whatever place history assigns him, something is clear. His celibacy notwithstanding, he has planted his seed. Perhaps it has taken a mouse to make us all more human. I still miss him.

About the Creator

Sigmund Fried

Not his real name, but he wishes it was. Wasted, waxing philosophical.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.