Tbilisi. Ciggies dispersed on cement.

Loitering kids vent on street curbs all week

Dingy chic.

Neighbours ill-wishing through flashy gnashers.

Blessings kissed firmly on squished cheeks.

Flickering blocks of yellow plastic anchored to car roofs.

Get a hold of one of those and a move on and you're a taxi driver.

Kids would shout after ya,

Yank your door bartering

“To the Pavilion for 5ლ?”

“Nah 6 minimum.” You’d answer them.

We would squat on the corner cracking sunflower seeds with our teeth, flicking shells at the pavement.

That’s our playground.

Before Minecraft.

Before fashion week.

When a trip to the only cinema in the city to witness the Russian overdub of ‘Madagascar’ was the most exquisite spectacle.

We’d be bluetoothing tunes to each other’s Motorolas, telling anecdotes… Like the one where Kostya goes to the apothecary and says,

“How much to get my penis dyed blue for my wedding night boss?”

He’s met with much confusion. So he goes on to clarify,

“Well, how else will I know for sure she’s a virgin?”

The guy goes, “When she says why is your dick blue what the hell will you tell her?”

To which old Kostya responds, “I’ll look her in the eye and say, how do you know what a penis is meant to look like?”

Virginity was always a talking point yet a taboo. With the nation being wholly Orthodox Christian and no one daring to suggest otherwise, the Georgian face of God was looming over every feast, every joke, and every romance.

We were raised with the essentialist notion that all men and like keys and women are locked doors.

A strong key won’t struggle unlocking some doors

The master key swiftly could open them all

If a faulty door opens to multiple keys,

Must be cheap, you can see that its’s flawed.

Back on the pavement, as soon as the lamppost flickered on, my grandma would stick her head out the window. Squealing from the 8th floor.

“I’m throwing you some change! Come catch it and get yourself in the lift!”

I’d argue back from the curb till the dinner had gone cold and my throat had gone sore.

Grandma doesn’t like having her picture taken. She’s twiddling a bare grapevine pretending not to catch the barrel of my lens in her sly periphery.

Iya was a chemist. A gentle cautious woman with aubergine hair down to the nape of her elegant neck.

The kind of woman who has an acute phobia of snails, lizards, and shattered glass believing young girls should be poised and well mannered. In short, I was often the source of embitterment that painted her aubergine roots grey. (She gave in eventually when the grey stopped cooperating.)

I could tell you about all the trouble I got up to and her nerves that I used up along the way but one December afternoon springs to mind in particular.

There’s this one park (Vaké park/the only park) that leaks into the forested hills running through the entire city. If you know your way around you can cut through the woods and poke your head out of the backstreets finding yourself at the opposite side of town. But you have to be down to do some climbing and or crawling.

My classmate Archil lived right above the park’s main entrance. We hadn’t been at school together since I moved to London three years prior, but we’d linked up for some mischief every summer.

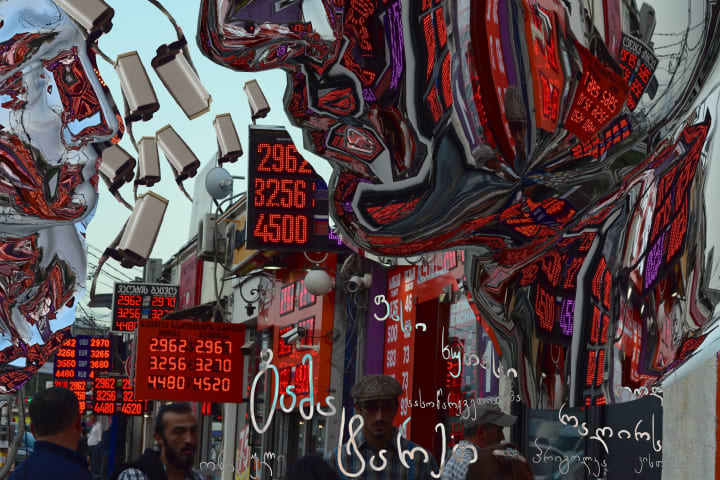

We’d dart through the bazaar stalls past the pawnshops, looking for corn puffs and Toybox.

We were galivanting through the back streets past our school after having prank called several friends and were thinking of moving on to enemies.

He’d always get nostalgic with me around. He’d dig up wounds and jokes that had been long buried by the rest of our class. I still kept a picture of them on my wall. Bit pathetic since most of them were now only my friends in the Facebook sense.

But there was one person who we’d both blocked, in both senses. She’d definitely end up on the enemy list (not that either of ours was particularly long for 13-year-olds). Ketuta.

How much more cliché can I get after saying that her honeyed laugh was still stuck ringing in my ears. We called her Tuta (mulberry in Georgian).

They’re rarely in season and scarce even on mulberry trees but when you see one, you’ll risk breaking a bone to get to the top and get a hold of the ripest handful. The mulberry ink doesn’t wash off easily, staining skin purple for days.

There was something about Ketuta that could overtake and capsize a heart, fishing it out delicately through the ego. We used to swing from deactivated pylons and secretly watch Columbian Telenovelas when my Grandma was asleep.

She was the only person Archil would talk to about his dad. Hers was in prison too. I remember how proudly she’d talk about him and kiss the tiny passport photo of him that she kept in her backpack.

The other kids looked up to her and it wasn’t always clear but she always in charge. She knew how to make anyone feel special. Her infectious cognac eyes could recruit you for war.

I won’t go into detail about how she broke Achiko’s boisterous heart and my cloying trust but needless to say we were harboring enough resentment for a mighty prank call. Besides Archil had come into some new information, “I haven’t told you yet, have I? Get this, my cousin Misha’s friend Luka’s neighbor Nino goes to her new school and Misha told me she said word for word that in our class, all the boys were in love with her and all the girls wanted to be her. Can you believe the nerve?! After all that other shit?”

“That sounds exactly like something she’d say!” I scoffed.

Turns out he still had her home number.

“I must’ve forgotten to delete it.’’ He mumbled.

We debated what exactly to say when she picked up, ideas ranging from vindictive to stupid.

And then I spat out, “What about… We’re doing a survey and we’d like to know if so far at your new school, all the boys love you and all the girls are sucking up or if they’ve yet figured out that you’re trash?’’

Achiko was exhilarated. “That’s perfect.” He snickered.

I used to lose my Georgian sim cards before each visit so there was no way Katuta would recognize this number.

We practiced some silly voices to throw her off. That alone was fun enough. I didn’t think we’d really do it. Maybe call and hang up. But as soon as that dial tone writhed out of the puny Motorola speakers, we froze like the Queen’s Guard. Each ring shrieked for an eternity. We gripped the corners of the phone with all four hands.

“Hello?” Her bouncy voice cut through the air. We stared at each other paralyzed. Archil opened his mouth. Sweat wormed down his forehead. Looked like when he’d forgotten his lines in the 3rd-grade production of Masha and the bear.

“Helloo...?” She chirped up again.

“Good afternoon, we’re doing a survey…” Archil murmured, swallowing his rehearsed character.

“What? Who is this?” She giggled.

I just snatched the phone and blurted my awfully gauche speech, immediately flipping the Motorola shut. We didn’t exactly burst into laughter afterward.

Archil took us out the woods onto the street corner where old ladies sell second-hand clothes and flowers for change.

He knew some of our classmates were headed to the bus stop down the road after rugby or dance. As soon as we saw them, we started exaggerating the story and regurgitating the theatrical voices to their amusement.

As we walked downhill, I was catching up with some of the girls telling them about my London school and my Motorola started ringing in my pocket. I flipped it open.

“Hi, I want to speak to Archil.” A deep gravelly voice ordered calmly.

I could see him further down the road with some other boys.

“Um… Sorry, he’s not here.”

“Oh yeah? Well not to worry, I’ll keep calling. Tell him to stick around Vaké park, shouldn’t be too far for him.” He hung up. Never been so unnerved by such a nonchalant tone.

I ran down shouting after him. And pushed past the other boys.

“Achiko! Listen we gotta go.”

What I said next, I immediately realized I shouldn’t have.

“This scary guy just called. He knows it was you and wants to track you down. I think we should go tell your mum.”

The boys chortled in cannon and started patting his back patronizingly.

“Well, you’d better go hide up your mamma’s skirt! The scary man is gonna get ya!”

“What? Shut up.” He snapped at me, “Why would I do that, are you crazy? She’s sending some dude after me? I’ll go face him myself.”

“Wait is this about that girl Katuta?” One of the boys leered. “Oh man, you’re screwed! Her dad just got out. He’s like the chief of the downtown gang. Better bring back up.” The boys kept walking and cackling.

From now on there was no reasoning with him. “I said I’d go, and I won’t go back on my word.” He announced to the boys.

We hurtled back through the woods panicking. Achiko wasn’t naturally the fighting kind, he’d get nosebleeds from existing and he never even liked playing rugby with the other boys. But his nature wasn’t to be consulted for from now on.

The phone rang again. This time, his.

His Nokia didn’t have a speaker function so all I heard was him muttering “Yes it is…” and “I’ll be there…”

He hung up. “The guy didn’t say when but we don’t have much time. I gotta make some calls…” he declared.

Next thing I know, we’re scurrying around blocks of flats past bellied gazebo men perched on tires playing backgammon. We end up in a dicey alleyway where a short chubby kid in a black hoodie and an oversize leather bomber jacket is leaning against the graffitied wall smoking a cigarette.

“Yo Achiko! How you holding up brother?” They hug sideways firmly slapping each other’s backs. After the introductions, Archil brings Sandro up to speed with our predicament. He nods and stubs out his cig, “Don’t worry bro, I got your back. Let's go over to Lazo’s and set an ambush plan. His dad won’t be home now and he’s got what we need.”

“Sorry what? You want to plan an ambush? Should you even be smoking at your age?” I jabbed.

“No-one asked you, auntie. You ain’t getting involved.” He snarled.

“I’m already involved, bro. I made the call, I spoke, I should apologize, and I don’t get why it’s your decision to—”

“Listen, I don’t know how they do things in London but here, you can save the apologies for your granny. We back each other because that’s what needs to be done and the girls don’t get in the way.”

I wanted to slap him so much. But I stuck with cynical comments instead.

Upstairs at Lazo’s the Achiko I knew had mutated into a douchebag. The two other ones started mapping out the park paths and planting themselves in hypothetical bushes. Sandro was wedging multicolored push pins in the cervices of his fist with the sharp ends sticking out like wolverine claws. And then Lazo emerged from his dad’s room holding a leather grip soviet combat knife. The boys leaped up in awe fussing over it as if it were a mini transformer.

“NO WAY. Wolverine over here is being dumb enough, you’re not bringing that. You’ll injure yourself just having that thing in your pocket! What the hell do you lot even know about wielding knives!” I screeched. It was getting less and less funny. “Oh yeah?” Sandro chuckled and swiveled around lifting his shirt to reveal a deep purple scar along his hip. “You have no idea.”

Achiko’s squad was in position. We’d entered the park through the woods and were now peeking out towards the main entrance searching the crowd.

There he stood, blocking the gates. Black Ray-Bans, black aviator jacket, black jeans. Crossed arms bolted in between two other built blokes. They were both bald but Katuta’s dad had gelled back black hair, and a Don Corleone mustache. They were all looking in with stony faces, squinting.

“Oh shit, the guy’s a tank,” I whispered.

Archil was clearly terrified but he strode up with a brave face, unconsciously tucking in his clenched jaw as far in as humanly possible. I really didn’t want to leave his side.

When they caught our eye, they started us to saunter down the footpath. We halted on the spot as Italian leather loafers inched towards us, stopping only an inch away.

“Let’s take a walk Achiko.” He cupped the back of Archil’s neck and walked him down the corner path. I staggered beside them quietly. His ‘men’ walked on either side trailing further behind us.

“We’re gonna have a chat man to man about what a man does and doesn’t do. That sound alright to you?” Achiko nodded faintly. His icy blasé voice felt like it had erupted from a cave he was hiding under his sheepskin jacket.

He stopped and turned to me, not letting go of Archil’s neck, “Mind if I take him for a little walk?” he said casually and kept walking before he could see me welling up.

I remembered all the stories of the uncle I never met who was stabbed at 16, my mother’s cousin who was taken in a car by a rival gang at 19 and never found, all the boys I’d heard about killing each other over honor, over a girl, the boys that were constantly told to be men, whatever that meant. But I didn’t want Sandro who had just squirmed out the woods to see me crying.

“I don’t want Achiko to get hurt” I blubbered.

He looked me in the eye and nodded and for a second while no one was around, I could see the fear in his eyes. I looked down at his fist, some of his pins had fallen off.

We tiptoed into the woods and followed the path from the side-lines, catching a glimpse of the black loafers. What we actually saw was Katuta’s dad squatting down to Achiko’s height and talking to him gently. And then he did something even more unexpected, he took off his impenetrable black Ray-Bans to reveal a pair of smiling cognac eyes, just like Ketuta’s.

“You kids are nosy, aren’t you?” He said smiling. We wriggled out from behind the trees barely meeting his glance. “You too…” He turned to the other side of the path where Lazo was blatantly crouching under some bushes.

“I’m sorry that you and Tuta fell out. It happens. But when it comes to old friends, it’s better to remember only the good things and let the rest go.” He said to me, laying a palm on my shoulder.

Then he put his shades back on and went, “Anyway have you heard that anecdote where Kostya goes to the apothecary?..”

No, I’m joking he didn’t say that.

About the Creator

Anamaria Burduli

Muti-media artist.

https://linktr.ee/anamariaburduli

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.