The Irish Potato Famine and Epigenetics

The Effects of Disaster

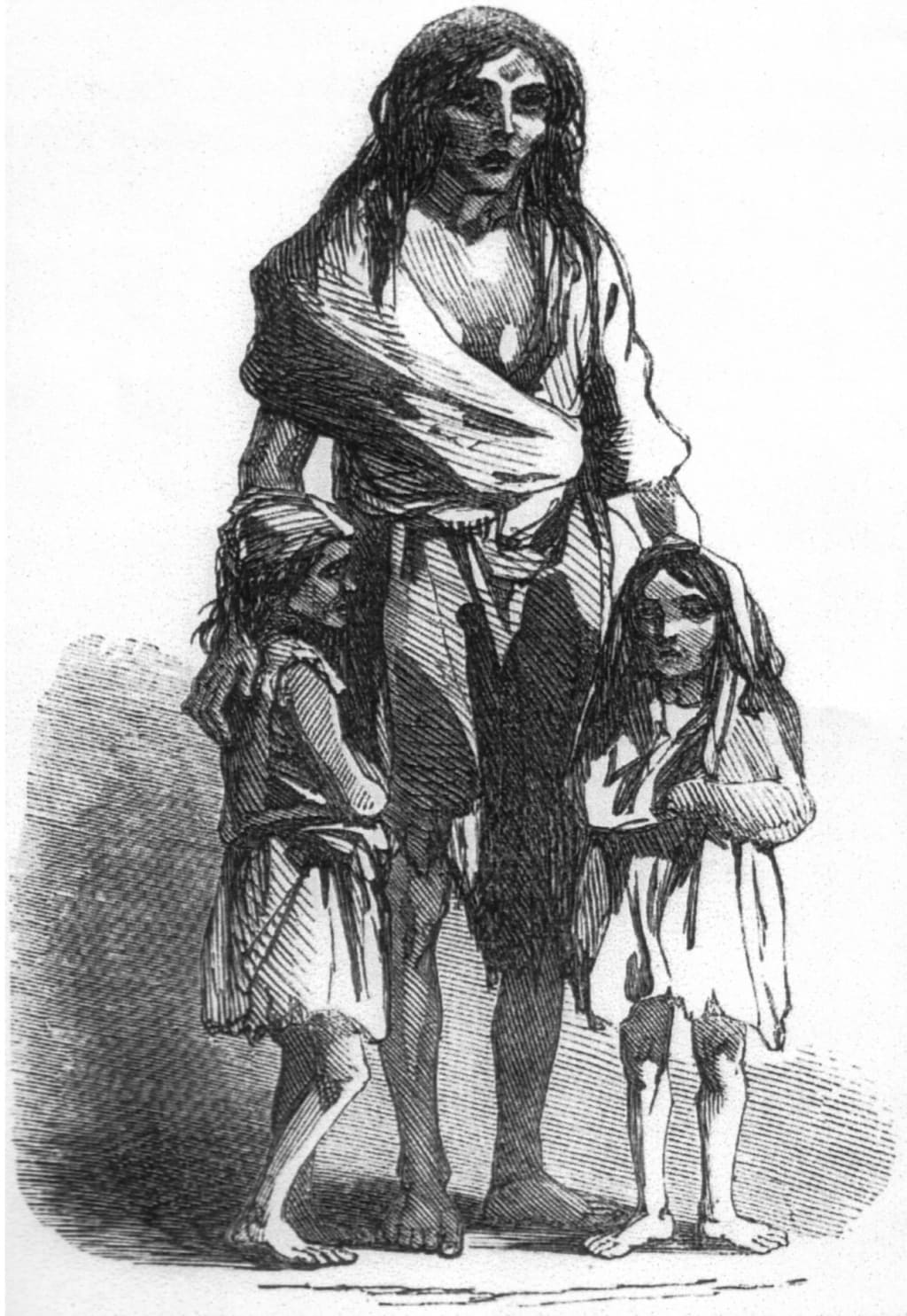

From 1845 to 1852, Ireland experienced one of its most devastating famines. Called the “Great Hunger,” it’s estimated to have killed one million Irish and forced a further two million to emigrate. But the effects have impacted more than the generations who survived. Through epigenetics, it has subsequently impacted the lives and heath of nearly every generation that came afterwards. Epigenetics is the study of the process by which genetic information is translated into the substance and behavior of an organism. Our genes, and the epigenetics that “sit” on them, determine our health, longevity, and dispositions. Not only can these be influenced by biology, but our own actions and experiences as well. Thus, our ancestors’ life experiences have influenced their own epigenetics, which in turn influence our parents’ and finally our own. When examining the Irish Potato Famine, the individual can be understood as the actual individual person experiencing the famine. The group thus becomes the population of Ireland during this time.

The effects of the famine produced many emerging characteristics. Environmental shocks during pregnancy affect the mother, the fetus, and the fetus’s primordial germ cells that will produce the grandchildren of the mother. Mental health has been shown to be particularly sensitive to epigenetic changes and, just like mortality and cardiovascular disease, the mental health outcome has been shown to be sensitive to early-life conditions. In his article "Famine Drives Madness," Patrick Tracey argues that in his family the “mental illness that was encouraged by the Great Irish Famine churched epigenetically through the generations for the next 150 years…[with] rates of psychosis more than doubling” (Tracey). Epigenetic marks play an important role in normal development because methylation patterns determine how stem cells develop into certain types of tissue which then maintain cell identity over the lifetime of an individual, thus demonstrating “how “nurture” gets written into the “nature” of our DNA code” (Tracey). They also play a central role for the development of cancer cells and cardiovascular diseases, determining old-age mortality. Irish culture was also severely affected by the famine.

After the famine, the epigenetic changes emerging seems to reflect the idea of a collective genetic memory. As a person’s experiences alter and influence their own epigenetics and those of their descendants, they are preparing their offspring in a way for the experiences they might face in life. Thus, our behavior, health, and dispositions can be affected by events in previous generations which have been passed on through a form of genetic memory. Kevin Kelly states this in his article “Wholes, Holes, and Spaces”: “Knowledge, truth, and information flow in networks and swarm systems” (Kelly, pg 45). What is DNA besides a complex double helix structure containing a network of genes and instructions for life. Independently, each gene is not important in and of itself. Many different species contain the same type of genes. However, it is the combination and cooperation of all our genes together, and the epigenetics that determine their translation, that make up the individual living organism. Thus, each person is merely a complex group system of genetic information, and under certain experiential circumstances like famine may succumb to its swarm-like structure. Kelly further argues that “much of what we collectively know derives from [these] few small areas” of genetic alteration (Kelly, pg 45). Even bacteria have been shown to collectively store information, perform decision-making, and even learn from past experiences. In his article “Look Who’s Talking: Communication and Quorum Sensing in the Bacterial World” Paul Williams maintains that though bacteria were considered autonomous unicellular organisms with little capacity for collective behavior, “we now appreciate that bacterial cells are in fact, highly communicative… [The] bacterial cell-to-cell communication mechanisms which co-ordinate gene expression usually, but not always, [occur] when the population has reached a high cell density” (Williams, pg 103). With a more prolonged experience of famine during sensitive periods, such as during gestation or early childhood, the epigenetic markers begin to reach a similar critical mass and thus collectively alter the genetic expression of individuals.

Additionally, the groupthink mentality of England and most of the world was shown to be a leading cause of the Irish Potato Famine, and proved to be detrimental to Irish culture. Groupthink, the practice of thinking or making decisions as a group, discourages creativity or individual responsibility. It produces many symptoms per David Henningsen’s article “Examining the Symptoms of Groupthink and Retrospective Sensemaking”, including “incomplete survey of alternatives, incomplete survey of objectives, failure to examine risks associated with the preferred choice, poor information search, selective bias in processing information, failure to reappraise alternatives, and failure to provide contingency plans” (Henningsen, pg 99). Several decisions leading up to and during the famine demonstrate this defective decision-making. When the potato blight reached Ireland, it found genetically homogenous crops which were easily affected. Only two types of potatoes were commonly grown. Infected tubers developed reddish brown patches beneath the skin, and quickly decayed to a foul-smelling inedible mush. Potatoes became a staple crop around 1780 when it thrived in the damp Irish climate, was easy to grow, and produced a high yield per acre. It quickly grew as a staple crop and a large part of the diet for even the poorest populations. Many assumed the disease would be temporary, and continued to reinvest the same percentage of their harvest despite the dwindling yields. This decision essentially caused much food to go to waste. Other governments, such as the English, haphazardly tried to aid the starving population, but lacked the necessary knowledge to be effective. In C N Trueman’s article The Great Famine Of 1845, he demonstrated that while England imported €100,000 worth of corn, “[they] had little knowledge of the country [they] were trying to help,” and did little to alleviate the growing crisis (Trueman).

Many governments unfortunately believed that “the Irish were simply… not worth the effort,” and were driven by free trade (Trueman). Like Henningsen stated, there simply was no contingency plan when landowners, able to get a better price for crops outside of Ireland, took their foodstuffs elsewhere. Despite this, “there was no export ban on Irish grain,” leaving many to suspect a deliberate decision to starve out the Irish (Tracey). Even sympathetic landowners were unable to support many of their tenants, overwhelmed by the poverty and pressured by their English or Anglo-Irish associates who did nothing (Trueman). Henningsen argues that “when group members have doubts about a position clearly favored by the group, they should be more cognizant of the pressures being exerted on them to go along with the group” (Henningsen, pg 102). However, the desire to conform and the pressures of the concurrence seeking step of groupthink make this nearly improbable. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Penal Laws had prohibited Irish Catholics from purchasing or leasing land, voting, holding political office, obtaining an education and entering certain professions, and from doing many other things necessary for a person to succeed and prosper in society. Although the laws had largely been reformed by 1793, the ideology behind these laws seemed to last well into recent history. The perception of the native Irish as unwelcome and undercutting wages meant they were the most affected. The most natively populated areas in the west of Ireland, where Gaelic was most commonly used, was thus one of the areas hit hardest by the emigration and deaths. The Gaelic language’s sharp decline is specifically linked to this time (Trueman).

With the higher susceptibility to diseases and health conditions emerging from the famine, there is also a greater need for medical intervention. In Kevin Kelly’s “The Made and the Born”, he argues that the realm of the born and the manmade is beginning to merge as we continue to discover new cures and treatments. Mental illnesses, cardiovascular disease, and cancer have some of the highest mortality rates. The most common way we have tried to treat these conditions has been through artificial pills, injections, and other medications. However, if that fails, mechanical or biological cardiac shunts may be needed to treat conditions resulting from cardiovascular disease. Certain cancers may cause patients to loss limbs and organs, which most often need to be replaced. Wei Sun, a Professor of Drexel's Department of Mechanical Engineering and Mechanics, has begun using 3D printers to replicate the cancer tumors of his patients. Through this, his hope is “to take the simulation they've created, attach it to tissue recreations to study cancer's growth process, and ultimately prevent cancer from forming” (Drexel Professor Fights Cancer with 3D Printing) This could lead to the individualized study of cancer patients using their own cells, thus personalizing and better targeting treatment for their conditions. Not to mention all the different manmade machines commonly used today to merely screen for these conditions.

In some instances, though, it’s ironic that as we attempt to undue the effects of our biology and nature, we look to nature itself for answers. It only makes sense that in order to treat a cancerous tumor, we begin to study the nature and process of that tumor itself. “As we look at human efforts to create complex mechanical things, again and again we return to nature for direction. Nature is thus more than a diverse gene bank harboring undiscovered herbal cures for future diseases” (Kelly, pg 16). It allows us to observe the complex phenomena of conditions, and provides the structure and knowledge needed for treatments. This convergence demonstrates the limitations of human adaptability, at least to William Wheeler, since it seems we are becoming more reliant on medical intervention. In his article “The Ant-Colony As An Organism” Wheeler states that “the range of adaptability in all organisms, even in zoologists, is very limited” (Wheeler, pg 81). However, isn’t our use of mechanical and biological treatments instead of physically adapting ourselves merely the way we have adapted? Working together almost as a group, the living body and population itself takes on new characteristics and abilities unseen in the individual parts. Timothy O’Connor points out in “Emergent Properties” that “it is certain that no mere summing up of the separate actions of those elements will ever amount to the action of the living body itself” (O’Connor, pg 91). One of the more positive characteristics of the group, per Kelly’s other article “Hive Mind” is the idea that “one part could fail without sinking the whole vessel” (Kelly, pg 25). Though any number of these conditions can cause a specific organ, limb, or system to fail, it does not necessarily mean the whole body will, especially with intervention. Likewise, although the population of Ireland decreased by nearly twenty-five percent, it did not completely crumble, emerging as the independent state of the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom constituent of Northern Ireland.

In conclusion, the Great Potato Famine was the most devastating famine Ireland has ever experienced, and its effects shaped the country and very genetic code of survivors. Through epigenetics, it has subsequently produced mental illnesses, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other conditions in subsequent generations. It demonstrates “how “nurture” gets written into the “nature” of our DNA code” (Tracey). When examining the population of Ireland during this time as the group, it does not, however, consider the actual people affected by the famine. It was mainly the poor, catholic Irish and not the Anglo-Irish or English who had settled there. There was almost a collective belief in the inferiority of the native Gaelic Irish and the group can thus be viewed as European society as a whole

Works Cited

Drexel Professor Fights Cancer with 3D Printing” Drexel University. Web.

McDonagh, Marese. "Impact of Great Famine on Mental Health Examined at Science Week." The Irish Times, 2013. Web.

Tracey, Patrick. "Famine Drives Madness for 150 Years." No Family Madder. Web.

Trueman, C N. “The Great Famine Of 1845” The History Learning Site, 25 Mar 2015. Web

Van Den Berg, Gerard J., and Pia R. Pinger. "A Validation Study of Transgenerational Effects of Childhood Conditions on the Third-Generation Offspring’s Economic and Health Outcomes Potentially Driven by Epigenetic Imprinting." IZA Discussion Paper Series, 2004. Web.

If you enjoyed this article, please feel free to leave a tip. Anything can help as I try to deliver all kinds of interesting content to readers. Please consider reading some of my other works, and I thank you so much for the support!

About the Creator

Kayla Bloom

Just a writer, teacher, sister, and woman taking things one day at a time in a fast-paced world. Don’t forget to live your dreams.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.