The Best Probiotic You'll Never, Ever Eat

When scientists tell you to "eat shit", are they trying to help?

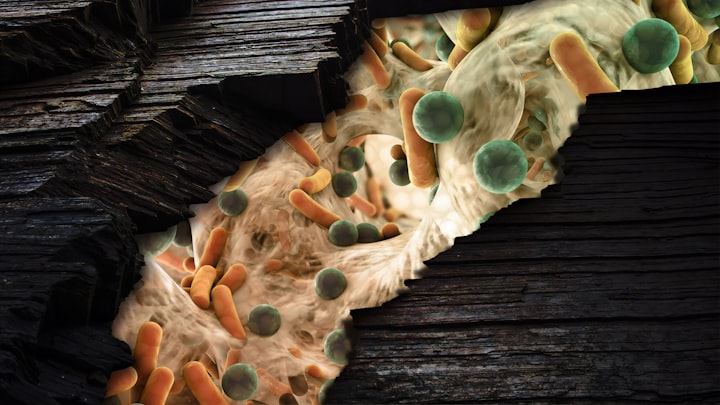

Many of us have seen commercials for probiotics: pills containing live bacteria that are said to somehow magically improve our digestive system and make us healthier. There’s never any real explanation of why eating live bacteria is good for us — the commercials just assure us that we should go out and buy their product right now, please and thank you.

In fact, there’s a reason why those claims are so vague: The FDA has very strict rules preventing companies from claiming that a product has specific health benefits. If a probiotic company claims that their product “cures IBS,” for example, the FDA will demand that they produce evidence through clinical trials. If a company makes no specific health claims, however, they can include a disclaimer and avoid FDA criticism.

Since my degree in genetics focuses on probiotics and microbiomes, I’m often asked for advice on products currently on the market. Is one company’s probiotic better than another’s?

Are generic and name-brand microbiomes the same?

What’s the best probiotic to take?

This last question always makes me chuckle, because I have an answer to it. This answer is technically correct, but the recipient will never be happy to hear it.

There’s an old joke about converting people to cannibalism, where a persuasive trickster turns to his flock and says, “What if I told you that there’s a single food that contains every component that a human needs to live?” He’s speaking, of course, about human flesh. And so, maybe it’s not so surprising that there is a probiotic that contains every microbe found in the digestive tract of a healthy person:

The best probiotic you can consume is a pill full of poop.

It sounds ridiculous, doesn’t it? But here are some facts worth considering:

- Most probiotics contain a couple billion bacteria. That seems like a lot — until you realize that there are trillions of bacteria in a healthy gut.

- Most probiotics contain between two and twelve different species of microbes. The average healthy gut environment has more than a thousand different species living in it.

- The most common types of bacteria found in commercially sold probiotics include Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. These “lactic acid bacteria” are typically found in fermented products like yogurt, milk, sauerkraut, and kimchi. Great — except that the refrigerated, aerated environment of yogurt is nothing like the warm, anaerobic environment in our gut. Some of these strains are also found in our gut, but a bacterium optimized to live in yogurt will not likely thrive in our gut.

- Microbiome transplants, which involve introducing bacteria from one animal’s gut into another animal, have been tested in mice for a wide variety of conditions. In one now-famous experiment, transplanting the microbes from an obese mouse into a healthy-weight mouse led to weight gain, even when the mouse was on the same diet. This means that the microbes are at least partly responsible for obesity! Unlike probiotics, entire microbiome transplants have demonstrated significant, long-term change in the animal’s physical appearance and health.

Given these facts, maybe popping a pill full of poop isn’t such a crazy idea after all!

Fecal microbiome transplants as medicine

The idea of a fecal transplant has been around for a long time. It dates all the way back to fourth-century China, when products derived from feces were used to treat severe cases of diarrhea or food poisoning. The idea was also used by the Bedouins and other groups in medieval Europe.

After the discovery of antibiotics such as penicillin, however, the idea of giving someone more microbes — the very things that cause disease — became abhorrent. In 1957, a microbiologist, Stanley Falkow, was fired from his hospital position for attempting to reduce diarrhea and indigestion by suggesting that patients swallow capsules containing their own feces. The idea of transplanting microbes never gained much traction with the medical community. This doesn’t mean, however, that everyone forgot about the idea of eating poop for health benefits. It’s just that fecal transplants moved into the realm of holistic medicine.

Think of fecal transplants and probiotics as tackling the same problem, but from opposite sides.

Eventually, however, they made a triumphant return, fueled by patients’ desperate search for effective treatments. Intestinal diseases, after all, are very difficult to fight. They’re often secondary infections — that is, they set in after a person’s system is already weakened. One particularly nasty bacterium, Clostridium difficile (commonly called C. diff), is known for preying on vulnerable hospital patients as they recover from surgery or other treatment. Such intestinal diseases are chronic, causing successive bouts of diarrhea and sickness, and can have a mortality rate as high as 30% among children and the elderly, who can lack the necessary resilience and strength to combat them.

Even for otherwise healthy adults, these illnesses can feel like a permanent curse. So it’s not surprising that some desperate patients might seek out alternative treatments on the internet. And that’s exactly how some people discovered the seemingly crazy idea of taking a fecal sample from someone healthy, turning it into a slurry, and inserting it into the rectum.

Wacky internet health advice is nothing new — but in this case, the treatment actually worked. Eventually, when skeptical doctors started trying fecal transplants in a clinical setting for curing C. difficile, they saw a success rate of 94% from a single dose. That kind of cure rate is unheard of.

Are “poop pills” the next health trend?

Right now, fecal transplants can only be prescribed for a single disease — C. difficile infections. That doesn’t mean, however, that fecal transplants will stay locked behind pharmacists’ counters for long. Companies are working on developing synthetic microbial communities, trying to isolate the strains of bacteria that serve as keystone species to make a gut microbiome do its job in a healthy individual. Fecal transplants are now being tested for conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

One study showed improvement of IBS symptoms in 49% of patients who consumed “poop pills,” versus improvement in only 29% of patients who consumed a placebo.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, the FDA blocks any company from advertising that its products treat a specific disease without clear and unarguable evidence. That restriction is why fecal transplants, especially in pill form, aren’t being widely advertised like probiotics.

Think of fecal transplants and probiotics as tackling the same problem, but from opposite sides. Probiotics are trying to add a couple individual strains of bacteria to promote general health effects. Fecal transplants are inserting an entire bacterial ecosystem, hoping to cure a specific disease. Probiotics are marketed directly to consumers, while fecal transplants are only prescribed by specialists, usually MDs.

Will we someday see advertising for “microbiome-transplant-in-a-pill” touted on television and the internet, promoted by celebrities like Oprah and Dr. Oz, and shared in viral posts by Instagram influencers? That day may be closer than you’d guess. In the meantime, there’s a lot more we need to understand about the workings of the complex, interdependent environment of the gut microbiome. So for now, it’s probably not a good idea to seriously entertain the thought of popping a poop pill into your mouth to start each day.

But perhaps, someday soon, we’ll consume the most effective probiotics we’ve discovered — bacterial communities derived from our very own intestinal tract.

Turning poop into gold, indeed.

About the Creator

Sam Westreich

PhD in genetics, bioinformatician, scientist at a Silicon Valley startup. Microbiome is the secret of biology that we’ve overlooked until now.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.